Beeple's Net Worth, History, And Origins

Among his early NFTs, "Crossroad," a commentary on the 2020 U.S. presidential election, made headlines by selling for $6.6 million in February 2021.

Brian

Brian

Written by: Andy Greenberg Compiled by: BitpushNews Tracy, Alvin

As a U.S. federal agent, Tigran Gambaryan pioneered the modern cryptocurrency investigation. Later at Binance, he got caught in the middle of the world's largest cryptocurrency exchange and a government determined to make it pay.

At 8 a.m. on March 23, 2024, Tigran Gambaryan woke up on his sofa in Abuja, Nigeria, where he had been dozing since pre-dawn prayers. The house around him, often accompanied by the hum of a nearby generator, was now unusually quiet. In that silence, the harsh reality of Gambaryan’s situation had come flooding back to him every morning for nearly a month: He and his colleague Nadeem Anjarwalla, from the cryptocurrency company Binance, were being held hostage, unable to obtain their own passports. They were being held under military guard in a barbed-wire compound owned by the Nigerian government.

Gambaryan rose from the couch. The 39-year-old Armenian-American, dressed in a white T-shirt, had a solid, muscular build and a right arm covered in Orthodox tattoos. His normally shaved head and neatly trimmed black beard were short and scraggly from a month’s absence. Gambaryan approached the compound’s cook and asked if she could buy him some cigarettes. Then he walked into the house’s inner courtyard and began pacing restlessly, calling his lawyer and other contacts at Binance and resuming his daily efforts to, as he put it, “fix this fucking thing.”

Just the day before, the two Binance employees and their crypto giant employer had been informed that they were about to be charged with tax evasion. The two men seemed to be caught in the middle of a bureaucratic conflict between an unaccountable foreign government and the most controversial player in the cryptocurrency economy. Now, not only were they being held against their will with no end in sight, they were also accused of being criminals.

Gambaryan spoke on the phone for more than two hours as the courtyard began to bake under the rising sun. When he finally hung up and returned to the house, he still hadn’t seen any sign of Anjarwalla. Anjarwalla had gone to the local mosque to pray before dawn that morning, and the caretaker who accompanied him kept a close watch on him. When Anjarwalla returned to the house, he told Gambaryan that he was going back upstairs to sleep.

A few hours had passed since then, so Gambaryan went up to the second-floor bedroom to check on his colleague. He pushed open the door and found Anjarwalla, apparently asleep, his feet sticking out from under the sheets. Gambaryan called to him at the door but got no response. For a moment, he worried that Anjarwalla might be having another panic attack—the young British-Kenyan Binance executive had been sleeping in Gambaryan's bed for several days and was too anxious to spend the night alone. Gambaryan walked through the darkened room—he had heard that the government caretaker of the house was behind on electricity bills and the generators were short of diesel, so all-day blackouts were common—and put his hand on the blanket. Strangely, the blanket sank, as if there was no actual human body underneath. Gambaryan pulled back the sheets. He found a T-shirt underneath, with a pillow stuffed inside. He looked down at the foot sticking out of the blanket and now saw that it was actually a sock with a water bottle inside.

Gambaryan didn’t call Anjarwalla again, nor did he search the house. He already knew that his Binance colleague and cellmate had escaped. He also immediately realized that his situation was about to get worse. He didn’t know yet how much worse it would be — that he would be in a Nigerian prison, charged with money laundering, which carries a 20-year sentence, without access to medical care even as his health deteriorated to the point of near-death, while being used as a pawn in a multi-billion-dollar cryptocurrency extortion scheme.

For that moment, he just sat in silence on his bed, in the dark, 6,000 miles from home, contemplating the fact that he was now completely alone.

TIGRAN GAMBARYAN Nigeria’s deepening nightmare stems at least in part from a conflict that has been raging for fifteen years. Ever since the mysterious Satoshi Nakamoto revealed Bitcoin to the world in 2009, cryptocurrency has promised a kind of libertarian holy grail: a digital currency that is not controlled by any government, is not subject to inflation, and can flow across national borders with impunity as if it existed in an entirely different dimension. Today, however, the reality is that cryptocurrency has become a multi-trillion dollar industry, largely run by companies with fancy offices and highly paid executives — countries whose laws and law enforcement agencies are able to bring pressure to bear on cryptocurrency companies and their employees just as they would on any other real-world industry.

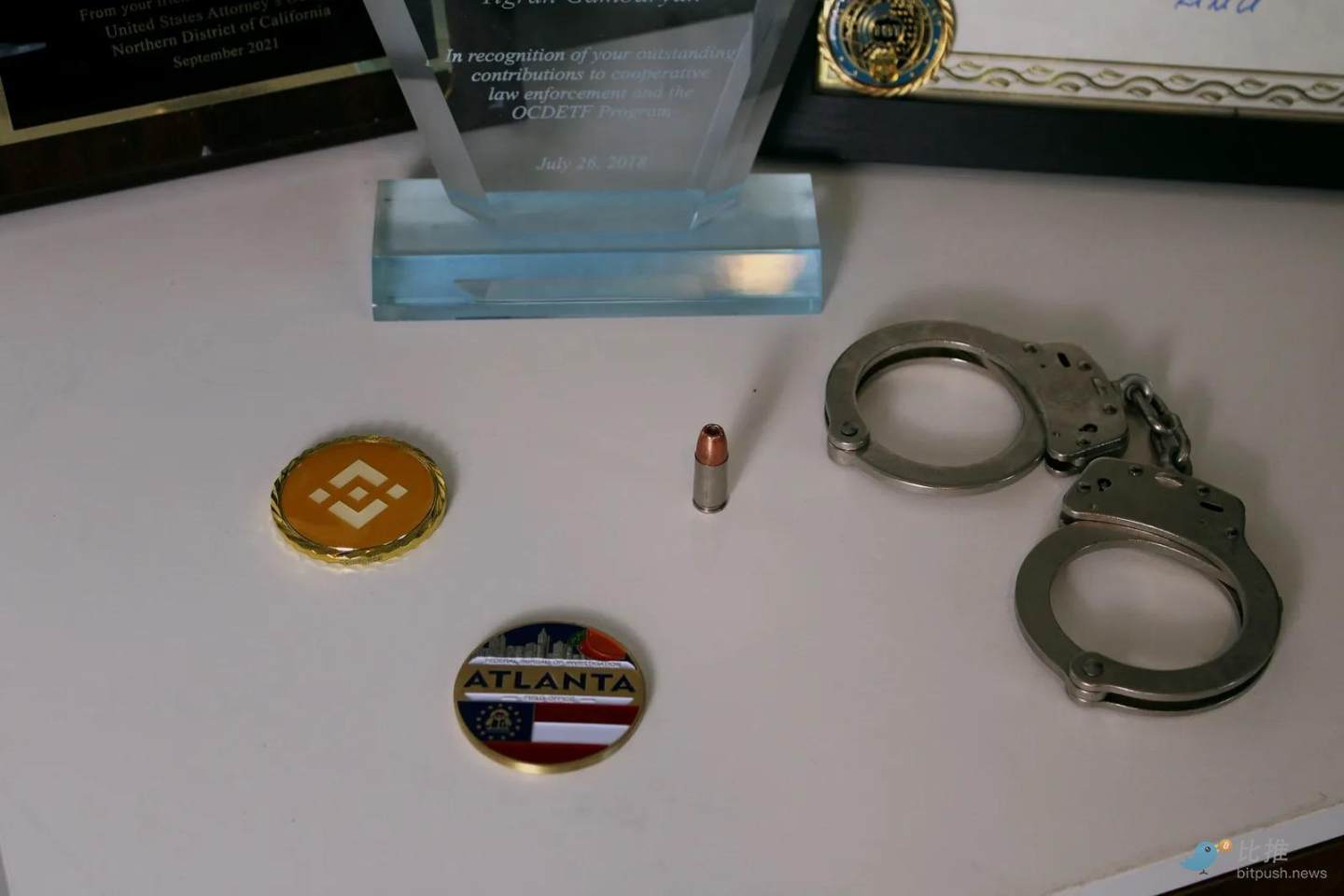

Before becoming one of the world’s most high-profile victims of the clash between disorderly fintech and global law enforcement, Gambaryan embodied that conflict in another way: as one of the world’s most effective and innovative crypto-focused enforcers. For a decade before joining Binance in 2021, Gambaryan served as a special agent with the Internal Revenue Service-Criminal Investigation (IRS-CI), responsible for implementing the tax agency’s enforcement efforts. While at IRS-CI, Gambaryan pioneered the technology to track cryptocurrencies and identify suspects by parsing the Bitcoin blockchain. With this “follow the money” tactic, he destroyed one cybercrime conspiracy after another and completely overturned the myth of Bitcoin’s anonymity.

Beginning in 2014, it was Gambaryan who tracked Bitcoin after the FBI took down the Silk Road dark web drug market, exposing two corrupt federal agents who stole more than $1 million while investigating the market—the first time blockchain evidence was included in a criminal indictment. In the following years, Gambaryan helped track $500 million worth of Bitcoin stolen from Mt. Gox, the first cryptocurrency exchange, ultimately identifying a group of Russian hackers as behind the theft.

In 2017, Gambaryan worked with blockchain analysis startup Chainalysis to create a secret Bitcoin tracking method that successfully found and helped the FBI seize the server hosting AlphaBay, a dark web criminal marketplace estimated to be 10 times larger than Silk Road. Months later, Gambaryan played a key role in taking down Welcome to Video, a cryptocurrency-funded child sex abuse video network that was the largest such marketplace to date. The operation led to the arrest of 337 users worldwide and the rescue of 23 children.

Finally, in 2020, Gambaryan and another IRS-CI agent tracked down and seized nearly 70,000 bitcoins that had been stolen from Silk Road by a hacker years earlier. At today’s prices, those bitcoins are worth $7 billion, making them the largest criminal forfeiture of any currency in history to the U.S. Treasury.

“He was involved in cases that covered almost all of the largest cryptocurrency cases at the time,” said Will Frentzen, a former U.S. attorney who worked closely with Gambaryan and prosecuted the crimes he uncovered. “He was very innovative in his investigations, in ways that many people hadn’t thought of, and very selfless in how he took credit.” In the fight against cryptocurrency crime, Frentzen said, “I don’t think anyone has had a bigger impact on this space than he has.”

After that storied career, Gambaryan turned to the private sector, making a decision that shocked many of his former colleagues in government. He became the head of the investigation team at Binance, a massive cryptocurrency exchange that handles tens of billions of dollars in daily transactions and is known for its indifference to whether its users are breaking the law.

When Gambaryan joined Binance in the fall of 2021, the company was already the subject of an investigation by the U.S. Department of Justice. Ultimately, the investigation revealed that Binance processed billions of dollars in transactions that violated anti-money laundering laws and circumvented international sanctions against Iran, Cuba, Syria, and the Russian-occupied region of Ukraine.

The Justice Department also noted that the company directly processed more than $100 million in cryptocurrency transactions from the Russian dark web criminal market Hydra, and in some cases, the sources of funds included the sale of child sexual abuse materials and the funding of funds designated as terrorist organizations.

Some of Gambaryan's old colleagues privately expressed dissatisfaction with his career change, and even thought he was "selling out to the enemy." However, Gambaryan firmly believed that he was actually taking on the most important role of his career. As part of Binance's efforts to clean up its image after years of rapid expansion, Gambaryan formed a new investigative team within the company, recruited many top agents from the IRS-CI and other law enforcement agencies around the world, and helped Binance to carry out unprecedented cooperation with law enforcement agencies.

Gambaryan said that by analyzing data with a trading volume that exceeds the combined volume of the New York Stock Exchange, the London Stock Exchange and the Tokyo Stock Exchange, his team has successfully helped solve cases such as child sexual abuse, terrorists and organized crime around the world. “We’ve assisted in thousands of cases around the world. I’ve probably had a greater impact at Binance than I ever had in law enforcement,” Gambaryan once told me. “I’m very proud of the work we’ve done, and I’m always willing to debate if anyone questions my decision to join Binance.”

While Gambaryan helped Binance create a more law-abiding image, the shift didn’t erase the company’s history as a lawless exchange, nor did it insulate it from the consequences of its past criminal behavior. In November 2023, U.S. Attorney General Merrick Garland announced at a press conference that Binance had agreed to pay $4.3 billion in fines and forfeitures, one of the largest corporate penalties in U.S. criminal justice history. Founder and CEO Changpeng Zhao was personally fined $150 million and sentenced to four months in prison.

The U.S. wasn’t the only country with a grudge against Binance. By early 2024, Nigeria had also begun to blame the company, not only for the compliance violations it admitted to in its U.S. plea agreement, but also because Binance It is accused of exacerbating the depreciation of the Nigerian currency, the naira. From the end of 2023 to the beginning of 2024, the naira depreciated by nearly 70%, and Nigerians exchanged their national currency for cryptocurrencies, especially "stablecoins" pegged to the US dollar.

Amaka Anku, head of Africa at Eurasia Group, said that the real reason for the depreciation of the naira was that the government of Nigeria's new President Bola Tinubu relaxed the exchange rate restrictions between the naira and the US dollar, and the foreign exchange reserves of the Central Bank of Nigeria were unexpectedly small. However, when the naira began to depreciate, cryptocurrencies as an unregulated way to sell the naira further exacerbated the depreciation pressure. “You can’t say Binance or any crypto exchange directly caused this devaluation,” Anku said, “but they certainly exacerbated the process.”

For years, cryptocurrency proponents have envisioned that Satoshi’s invention would provide a safe haven for citizens of countries facing inflation crises. That moment has finally arrived, and the government of Nigeria, Africa’s largest economy, is furious. In December 2023, a committee of the Nigerian Congress asked Binance’s top brass to appear at a hearing in the capital, Abuja, to explain how they were correcting their alleged mistakes. In response, Binance convened a Nigerian delegation, and as a symbol of the company’s commitment to working with law enforcement agencies and governments around the world, Tigran Gambaryan, a former federal agent and star investigator, naturally became a member of the delegation.

However, before resorting to extreme measures such as coercion and hostage-taking, (the perpetrators) first made demands for bribes.

In January 2023, Gambaryan had just arrived in Abuja for a few days and his trip was going smoothly. As a show of goodwill, he met with investigators from Nigeria’s Economic and Financial Crimes Commission (EFCC). The EFCC is basically Gambaryan’s counterpart to the IRS in the United States, responsible for combating fraud and investigating government corruption, among other tasks, and discussed the possibility of providing cryptocurrency investigation training to the agency’s employees. He then participated in a roundtable meeting with Binance executives and members of the Nigerian House of Representatives, where everyone promised to resolve their differences together in an amicable atmosphere.

One night, while Gambaryan and Ogunjobi were dining at the table with a group of Binance colleagues, a Binance employee received a call from the company’s lawyer. After the pleasantries, the lawyer told Gambaryan that the meeting with Nigerian officials was not as friendly as it seemed. The officials were now demanding $150 million to resolve Binance's problems in Nigeria - and they wanted the payment to be made in cryptocurrency, directly into the officials' crypto wallets. Even more shocking, the officials hinted that the Binance team could not leave Nigeria until the payment was in place.

Gambaryan was so shocked that he didn't even have time to explain or say goodbye to Ogunjobi. He hurriedly packed up the Binance employees and hurried out of the restaurant and returned to the Transcorp Hilton Hotel conference room to discuss the next response plan. Paying this obvious bribe would violate the United States' Foreign Corrupt Practices Act. If they refused, they could be detained indefinitely. Ultimately, the team decided on a third option: leaving Nigeria immediately. They spent the whole night in the conference room urgently planning how to get all Binance employees on a plane as soon as possible, change flights, and leave earlier than the next morning.

The next morning, the Binance team gathered on the second floor of the hotel, their bags packed, and they tried to avoid the lobby in case Nigerian officials were waiting for them and tried to stop them from leaving. They took a taxi to the airport, nervously passed through security, and boarded the plane back home without any problems. Everyone felt as if they had dodged a disaster.

Soon after returning to the suburbs of Atlanta, Gambaryan received a call from Ogunjobi. Gambaryan said Ogunjobi was very disappointed with the bribery demands on the Binance team and was shocked by the behavior of his fellow Nigerians. Ogunjobi suggested that Gambaryan report the bribery to the Nigerian authorities and ask them to launch an anti-corruption investigation.

Finally, Ogunjobi arranged a call between Gambaryan and EFCC official Ahmad Sa’ad Abubakar. Abubakar was introduced as the right-hand man of Nigeria’s National Security Advisor, Nuhu Ribadu. Ogunjobi told Gambaryan that Ribadu was an anti-corruption fighter who had even given a TEDx talk. Now, Ribadu invited Gambaryan to meet with him in person to resolve Binance’s problems in Nigeria and get to the bottom of the bribery.

Gambaryan told his Binance colleagues about the call, and it sounded like an opportunity to resolve the company’s woes in Nigeria. So Binance executives and Gambaryan began to think that perhaps he could use the invitation to return to Nigeria and unravel the company’s increasingly complicated relationship with the Nigerian government. Although the idea sounded risky—after all, they had hurriedly fled the country just weeks ago—Gambaryan believed he had received a friendly invitation from a powerful official and a personal guarantee from his friend Ogunjobi. Local Binance staff also told Gambaryan that they had verified and believed the solution was solid.

Gambaryan told his wife, Yuki, about the bribe and the invitation to return to Nigeria. For her, the offer was clearly too dangerous. She repeatedly asked Gambaryan not to go.

Gambaryan now admits that perhaps he still had the mindset of a U.S. federal agent—the one that came with a sense of responsibility and security. “I guess that’s what’s left over from the past: when duty calls, you do it,” he said. “I was asked to go.”

So, in what he now considers one of the most unwise decisions of his life, Gambaryan packed his bags, kissed Yuki and their two children, and left in the early morning of February 25 to catch a flight to Abuja.

The second trip began with Ogunjobi picking him up at the airport, who reassured him and consoled him during the drive to the Transcorp Hilton and over dinner. This time, Gambaryan was accompanied only by Binance’s East Africa country manager, Nadeem Anjarwalla, a British-Kenyan who had just graduated from Stanford University and had a baby at home in Nairobi.

However, when Gambaryan and Anjarwalla walked into a meeting with Nigerian officials the next day, they were surprised to find that Abubakar had brought along staff from the EFCC and the Central Bank of Nigeria. It soon became clear what the meeting was about: this was not about corruption in Nigeria. At the beginning of the meeting, Abubakar asked about Binance’s cooperation with Nigerian law enforcement agencies, and then turned the topic to the EFCC’s request for transaction data on Binance’s Nigerian users. Abubakar said that Binance only provided data for the past year, not all the data he requested. Gambaryan felt that he had been caught by surprise, which he explained as an oversight caused by the temporary request, and promised to provide all the required data as soon as possible. Despite Abubakar’s irritation, the meeting went on, and ended with a friendly exchange of business cards.

Gambaryan and Anjarwalla were left in the hallway, awaiting their next appointment. After a while, Anjarwalla went to the bathroom. When he returned, he said he heard angry voices from a nearby conference room from some officials he had just met, Gambaryan remembered saying.

After waiting for nearly two hours, Ogunjobi returned and led them into another conference room. Gambaryan remembered that the officials in this conference room looked solemn and the atmosphere was extremely serious. Everyone sat in silence, as if waiting for someone to arrive - Gambaryan didn't know who that person was. He noticed that Ogunjobi had a shocked look on his face and didn't dare to look him in the eye. "What the hell is going on?" he thought to himself.

At this time, a middle-aged man named Hamma Adama Bello walked into the room. He was an EFCC official, in a gray suit, unshaven, and in his forties. Without greeting or asking questions, he placed a folder on the table and immediately began to lecture Gambaryan, as he recalls him: Binance was “destroying our economy” and funding terrorism.

He then told Gambaryan and Anjarwalla what was going to happen: They would be taken back to their hotel to pack their bags and then moved to another location, where more EFCC officials and some central bank personnel would be present until Binance handed over all the transaction data involving every Nigerian who had ever used the platform.

Gambaryan felt his heart racing, and he immediately said that he had no authority and could not provide such a large amount of data—the purpose of his visit was actually to report the bribery to Bello’s agency.

Bello seemed a little surprised to hear about the bribery, as if he had never heard of it before, but soon ignored it. The meeting was over. Gambaryan quickly sent a text message to Noah Perlman, Binance’s chief compliance officer, telling him they might be detained. Then the officers took their phones.

The two were led outside to a black Land Cruiser with dark window film on the windows. The SUV took them back to the Transcorp Hilton Hotel, where they were taken to their rooms—Anjarwalla with Bello and another officer, and Gambaryan with Ogunjobi. They were told to pack their bags. “You know how bad this is, don’t you?” Gambaryan remembers telling Ogunjobi. Ogunjobi, barely able to look him in the face, responded, “I know, I know.” The Rand Cruiser then took them to a large, two-story house in a walled compound with marble floors, bedrooms large enough for two Binance employees and several EFCC officials, and a private chef. Gambaryan later learned that the house was the government-designated residence of Ribadu, the national security adviser, but that Ribadu had chosen to live in his own home, leaving the place for official use—in this case, as a temporary place to hold them. Bello made no further requests that night. After eating a Nigerian stew prepared by the house’s cook, Gambaryan and Anjarwalla were told to rest. Gambaryan lay in bed, anxious and almost in a panic because he had no phone and could not contact the outside world, or even tell his family where he was.

It was not until 2 a.m. that he finally fell asleep, and a few hours later he woke up to the sound of the morning muezzin prayer. Too anxious to stay in bed, he walked out to the yard of the house, smoked a cigarette and thought about his current predicament: he was a hostage, trapped in the financial crime he had dedicated his life to fighting.

But even more than the sense of irony, what was even more overwhelming was the feeling of complete uncertainty. "What will happen to me? What will Yuki go through?" he thought to his wife, his heart filled with anxiety. "How long will we be here?"

Gambaryan stood in the yard smoking until the sun rose.

The interrogation followed.

Breakfast was prepared by the cook, but Gambaryan was too stressed to eat. Bello sat down with them and told them that to release them, Binance would have to hand over all data on Nigerian users and ban Nigerian users from peer-to-peer trading. Peer-to-peer trading is a feature on the Binance platform that allows traders to post cryptocurrency sales based on exchange rates that they partially control, which Nigerian officials believe has contributed to the depreciation of the naira.

In addition to these demands, there was another unspoken demand in the meeting room: Binance needed to pay a large sum of money. While Gambaryan and Anjarwalla were being held, Nigerians were communicating with Binance executives through back channels, and the company learned they were demanding billions of dollars. According to people involved in the negotiations, government officials even publicly told the BBC that the fine would be at least $10 billion, more than double the highest settlement Binance has ever paid to the United States. (Binance did offer “deposits” based on estimates of the company’s tax liabilities in Nigeria, but those proposals were never accepted, according to several people familiar with the matter. Meanwhile, the day after Gambaryan and Anjarwalla were detained, the U.S. Embassy received a strange letter from the EFCC stating that Gambaryan was being detained “solely for constructive dialogue” and had “voluntarily participated in these strategic conversations.”

Gambaryan repeatedly explained to Bello that he had no real power over Binance’s business decisions and could not meet his demands. Bello did not change his tone after hearing this, and continued his long-winded accusation that Binance had caused Nigeria damage and claimed that Nigeria should be compensated. Gambaryan recalled that Bello sometimes showed off the guns he carried and showed photos of himself training with the FBI in Quantico, Virginia, as if to show his authority and connection to the United States.

Ogunjobi also participated in the interrogation. Gambaryan said he was quieter and more respectful than Bello, but no longer the respectful student. When Gambaryan mentioned the many ways he had helped Nigerian law enforcement, Ogunjobi responded that he had seen comments on LinkedIn saying that Binance hired him only to create a false sense of legitimacy, which shocked Gambaryan, especially after their long conversation.

Angry and unable to meet Nigeria's demands, Gambaryan asked to see a lawyer, contact the U.S. Embassy and return his phone, but all requests were denied, although he was allowed to call his wife in the presence of guards.

In the stalemate with EFCC officials, Gambaryan He told them he would not eat unless he was allowed to see a lawyer and contact the embassy. He began a hunger strike, trapped in the house, guarded by government agents and guards, sitting on the sofa all day watching Nigerian TV. After five days of hunger strike, officials finally relented. He and Anjarwalla had their phones returned but were told not to contact the media and their passports were seized. They were then allowed to meet with local lawyers hired by Binance. After a week of detention, Gambaryan was taken to the Nigerian government building to meet with local diplomats. The diplomats said they would monitor Gambaryan's situation but, so far, there was no way to free him. Then they began a "Groundhog Day" routine, as Gambaryan later told his wife, walking around. The house was large and clean, but shabby, with a leaky roof and no electricity for many days. Gambaryan befriended the cook and some of the guards, watching pirated episodes of Avatar: The Last Airbender with them. Anjarwalla began doing yoga every day and drinking smoothies that the cook made for him.

Anjarwalla seemed to be suffering more from the anxiety of their captivity than Gambaryan, and he was upset about missing his son’s first birthday. Nigeria had seized his British passport, but they didn’t realize that Anjarwalla also had his Kenyan passport. He and Gambaryan joked about running away, but Gambaryan said he never seriously considered it. He told himself that Yuki had told him “not to do anything stupid,” and he wasn’t going to take any chances.

One day, Anjarwalla lay on the couch and told Gambaryan that he felt sick and cold. Gambaryan covered him with blankets, but he was still shaking. Eventually, Nigeria took Anjarwalla and Gambaryan to a hospital in another black Land Cruiser, where Anjarwalla was tested for malaria. The test came back negative, and the doctor told Anjarwalla that he had just had a panic attack. Every night since then, Gambaryan said, Anjarwalla would sleep next to him because he was too scared to sleep alone.

During Gambaryan and Anjarwalla’s second week in captivity, Binance agreed to the request, shutting down its peer-to-peer trading function in Nigeria and reversing all naira transactions. EFCC officials told Gambaryan and Anjarwalla to pack their bags and prepare for their release. The two took the good news seriously, and Gambaryan even took a video of the house on his phone as a memento of this strange life.

However, before they were about to be released, government guards took them to the EFCC office. The agency’s chairman demanded confirmation that Binance had handed over all the data on Nigerian users. When he learned that Binance had not, he immediately reversed the release decision and sent the two back to the hotel.

At this point, cryptocurrency website DLNews first reported that two Binance executives were detained in Nigeria, although they did not disclose their names. A few days later, The Wall Street Journal and Wired also confirmed that it was Anjarwalla and Gambaryan who were detained.

Bello was angry about the news leak, and Gambaryan recalled that Bello put the blame on him and Anjarwalla. Bello told them that if they handed over the data the government requested, they would be free. Gambaryan lost his patience and asked Bello, "Do you want me to take it out of my right pocket or my left pocket?" He recalled standing up and dramatically pulling something out of one pocket and then out of the other. “There was no way I could provide that data.”

As weeks passed, negotiations were still stagnant. Ramadan began, and Gambaryan rose with Anjarwalla every morning to pray and fast with him during the day in a friendly show of solidarity.

After nearly a month of hardship, however, things suddenly changed. One morning, Gambaryan woke up to see that Anjarwalla had returned from the mosque, and when he went to look for his companions, he found only a shirt stuffed under a pillow and a water bottle in a sock on his bed—Anjarwalla had escaped.

Later, Gambaryan learned that Anjarwalla had managed to flee Nigeria on a flight. He speculated that Anjarwalla might have somehow jumped over the compound’s wall, managed to evade the guards—who often slept in the mornings—and then paid for a taxi to the airport, where he boarded the plane using his second passport. Gambaryan had realized that his situation in Nigeria was about to change dramatically. He walked out to the yard and recorded a selfie video to send to his wife, Yuki, and his colleagues at Binance, talking to the camera as he walked. "I have been detained by the Nigerian government for a month, and I don't know what will happen after today," he said calmly and in control. "I have done nothing wrong. I have been a policeman all my life. I only ask the Nigerian government to let me go, and I ask the US government for help. I need your help, everyone. I don't know if I can get out without your help. Please help me." When the Nigerians learned that Anjarwalla had escaped, the guards and custodians took Gambaryan's phone and began a frantic search of the house. Soon, they disappeared and were replaced by new people.

Anticipating that something more serious might be coming, Gambaryan managed to convince a Nigerian to quietly lend him his cell phone, then went to the bathroom to call his wife, reaching Yuki late at night. Gambaryan said it was the first time in their 17-year relationship that he had told her he was scared. Yuki cried, and she went into the closet to talk to him so as not to wake the children. Then, abruptly, Gambaryan hung up the phone—someone was coming.

A military official told Gambaryan to pack his bags and said he was being released. He packed his things, knowing that couldn't be true, and walked outside to his car, where he saw Ogunjobi sitting. When Gambaryan asked Ogunjobi where they were going, Ogunjobi vaguely replied that maybe he was going home, but not today—and then silently looked at his phone.

The car eventually pulled into the EFCC compound, not stopping near the headquarters but heading straight to the detention facility. Gambaryan angrily yelled at the guards, no longer caring about offending them.

As he was led into the EFCC detention building, he saw a group of people who had been guarding him in the safe house, now also in the cell, being investigated for possibly allowing Anjarwalla to escape, or even suspected of colluding with him. Gambaryan was then put in his own cell alone.

The cell, as Gambaryan described it, was like a windowless "box," with only a timed cold shower and an ill-fitting Posturepedic mattress. The room was crawling with as many as half a dozen cockroaches of varying sizes. Despite the stifling heat in Abuja, the cell had no air conditioning or ventilation, only what Gambaryan remembers as “the loudest fan in the world” running day and night. “I can still hear that damn fan,” he said.

Solitary in that cell, Gambaryan said he began to feel disconnected from his body, his surroundings, and the hell that was it all. That first night, he didn’t even think about his family, his mind was blank, and he didn’t notice the cockroaches in his room.

By the next morning, Gambaryan hadn’t eaten in more than 24 hours. Another detainee gave him some biscuits. He soon realized that his survival depended on Ogunjobi, who would come to bring him food every few days and sometimes let him use his phone when he was briefly released from solitary confinement. Soon, Gambaryan’s former guards began sharing the meals his family brought him, while Ogunjobi came less and less often, sometimes even refusing to let him use his phone. The young man who had picked him up at the airport, who admired Gambaryan’s work, seemed to have changed. “You could almost say he enjoyed the control he had over me,” Gambaryan said.

The Nigerian who had been his guard just a few days before was now Gambaryan’s only friend. He taught a young EFCC agent how to play chess, and they played together during the brief free time before being sent back to their cells.

A few days into his stay at the detention center, Gambaryan’s lawyer visited him and told him that he was now charged with money laundering, in addition to the original tax evasion charges. These new charges meant he could face 20 years in prison.

During his second week at the detention center, Gambaryan’s son turned 5. On his birthday, Gambaryan was allowed to use the EFCC phone to call his family and smoke a few cigarettes, but not otherwise. He spoke on the phone for 20 minutes with his wife, who he said was “melting apart” with anxiety, and then talked to his children. His son still didn’t understand why he wasn’t home. Yuki told Gambaryan that he had begun crying for him at random times and would often come sit in his chair in their home office. Gambaryan explained to his daughter that he was still working out legal issues with the Nigerian government. He later learned that his daughter had looked up his name and read the news two weeks after he was detained and knew more than she had let him know.

Besides occasional meetings with his fellow inmates, Gambaryan had two books to pass the time—a Dan Brown novel given to him by an EFCC staffer and a Percy Jackson teen novel brought in by his lawyer. He had little else to keep him busy. His mind cycled between angry curses, self-blame and emptiness.

“It was torture,” Gambaryan said. “I knew if I stayed there I would go crazy.”

Although Gambaryan felt extremely alone, he was not forgotten. While he was in the EFCC’s cell, a loose group of friends and supporters had begun to respond to his cries for help in the video. However, he soon realized that if he wanted to be free, real help would not come from the Biden administration.

Inside Binance, Gambaryan’s first text message about his detention immediately triggered endless crisis response meetings, hiring lawyers and consultants, and contacting any government officials who might have influence in Nigeria. Will Frentzen, a former U.S. attorney from the Bay Area who had handled many of Gambaryan's big cases, took over Gambaryan's case as his personal defense attorney after moving to the private firm Morrison Foerster. Gambaryan's former colleague Patrick Hillman had worked on crisis response with former Florida Congressman Connie Mack and knew Mack's experience handling hostage situations. Mack agreed to lobby his contacts in the legislative community for Gambaryan. Gambaryan's old colleagues at the FBI also immediately began to pressure the FBI to push for Gambaryan's release.

However, at the top of the U.S. government, some of Gambaryan's supporters said their requests for help were met with a cautious response. "From the first day Gambaryan was detained, State Department staff have been working to ensure his safety, health, provide legal assistance, and promote his release after he was criminally charged," a senior State Department official told WIRED in an interview, requesting anonymity in accordance with department policy. Yet the Biden administration initially seemed to be ambivalent about Gambaryan, according to several people involved in the matter. After all, Binance had just agreed to pay a huge fine to the Justice Department, the government was not friendly to the entire cryptocurrency industry, and Binance had a bad reputation, "toxic" - as one Gambaryan supporter described it.

"They felt that maybe Nigeria did have a case," Frentzen said. "They were not sure what Tigran had done there. So they all backed off."

Gambaryan got caught up in Nigeria's predicament at an extremely dangerous geopolitical moment. The U.S. ambassador to Nigeria retires in 2023, and the new ambassador will not officially take office until May 2024. At the same time, Niger and Chad have asked the United States to withdraw its troops from both countries as they strengthen their ties with Russia, while Nigeria is a key U.S. military ally in the region. That made negotiations for Gambaryan’s release more complicated than with other countries that have wrongfully detained U.S. citizens, such as Russia or Iran. “Nigeria was the only option left, and they knew it,” Frentzen said. “So, the timing was really bad. Tigran is really one of the unluckiest people in the world.” While Gambaryan was held in a guest room, it might have been clearer at the diplomatic level that he was a hostage, said Mack, a former congressman who lobbied for his release. The criminal charges against him, however, complicated the situation. “The U.S. government went with that narrative,” Mack said. “They wanted to let the legal process play itself out.” Frentzen and his senior colleague at Morrison Foerster, former DNI general counsel Robert Litt, said they began reaching out to the White House to explain how weak the criminal case against Gambaryan was. Of the more than 300 pages of “evidence” submitted by Nigerian prosecutors, only two mentioned Gambaryan himself: one was an email showing that he worked at Binance; the other was a scan of his business card.

Despite this, the U.S. government did not intervene in Gambaryan’s criminal prosecution in the following months. To Frentzen, it was a shocking situation: a former IRS agent who had worked for the federal government for many of the major cryptocurrency criminal cases and asset forfeiture cases in history was supported by the government’s mere silence in this seemingly cryptocurrency extortion case.

“This guy has helped the United States recover billions of dollars,” Frentzen recalled thinking, “and we can’t save him from the Nigerian predicament?”

In early April, Gambaryan was brought to court for his arraignment. He was on public display in a black T-shirt and dark green pants, becoming a symbol of the evil forces destroying Nigeria’s economy. As he sat on a red sofa to hear the charges, local and international media swarmed around him, cameras sometimes just feet from his face, and he could barely hide his anger and humiliation. "I felt like a circus animal," he said.

In this hearing, the next, and subsequent court documents, prosecutors argued that Gambaryan would likely flee if he was allowed bail, citing Anjarwalla's escape as an example. They bizarrely emphasized that Gambaryan was born in Armenia, although his family left the country when he was 9. Even more absurd, they claimed that Gambaryan and other inmates at the EFCC detention facility had hatched a plot to use a body double to escape, which Gambaryan said was a complete lie.

At one point, prosecutors made it clear that Gambaryan's detention was vital to the Nigerian government as a lever for pressure on Binance. “The first defendant, Binance, is a virtual operation,” the prosecutor told the judge. “The only one we can catch is this defendant.”

The judge refused to grant Gambaryan bail, deciding to keep him in custody. After two weeks in solitary confinement, he was transferred to a real prison, Kuje Prison.

Guards—including the usual Ogunjobi—put Gambaryan in a van. Ogunjobi handed him back his cigarette, which he smoked throughout the hour-long drive from downtown Abuja through what looked like a slum on the outskirts of the city. During the journey, Gambaryan was allowed to call Yuki and a number of Binance executives, some of whom hadn’t heard from him in weeks.

During the drive to Kuje prison, passing through prisons known for their abysmal conditions and past incarceration of Boko Haram suspects, Gambaryan said he felt numb, "disconnected from the outside world," having completely relinquished control over his fate. "I was living hour by hour, minute by minute," he said.

As they arrived and passed through the prison gates, Gambaryan got his first glimpse of the prison's low-slung buildings, painted pale yellow, many still destroyed by an ISIS attack that allowed more than 800 inmates to escape almost two years ago. Gambaryan's EFCC guards took him inside the prison and took him to the prison director's office. He later learned that the prison director was keeping him under close surveillance on the instructions of National Security Adviser Ribadu.

Gambaryan was then taken to the “isolation unit,” a unit for high-risk inmates and VIP prisoners willing to pay extra for special treatment. The 6-by-10-foot room contained a toilet, a metal bed frame with what Gambaryan called a “simple blanket” as a mattress, and a window with metal bars. Compared to the EFCC dungeon, the room was an upgrade: He had sunlight and fresh air—albeit polluted by garbage fires a few hundred meters away—and a view of trees that were swarmed with bats at night.

On Gambaryan’s first night in prison, it rained and a cool breeze blew in through the windows. “Even though the conditions were bad,” Gambaryan said, “I felt like I was in heaven.”

Soon after, Gambaryan got to know his neighbors. One is a cousin of Nigeria's vice president, another is a suspect in a $100 million fraud case awaiting U.S. extradition, and the third is Abba Kyari, a former deputy police chief in Nigeria who is being indicted by the U.S. for alleged bribery, though Nigeria has rejected the U.S. extradition request. Gambaryan believes Kyari's case is more about his falling out with corrupt Nigerian officials. Gambaryan said Kyari has a lot of influence in prison and the other prisoners basically work for him. Kyari's wife would bring home-cooked meals to everyone, even the guards. Gambaryan especially liked some kind of dumplings from northern Nigeria that Kyari's wife made, and she would make extra for him. He would share with Kyari the takeout that the lawyer brought from the fast food restaurant Kilimanjaro, and Kyari especially liked their Scotch eggs. Gambaryan’s neighbors taught him the unspoken rules of prison life: how to get a cellphone, how to avoid run-ins with prison staff, and how to avoid violence from other inmates. Gambaryan insists that he never bribed the guards — though they sometimes demanded astronomical sums of tens of thousands of dollars — but that he still received protection because of his close relationship with Kyari. “He’s like my Red,” Gambaryan said, comparing Kyari to Morgan Freeman’s character in “The Shawshank Redemption.” “He was the key to my survival.” Over the next few weeks, Gambaryan’s case continued, and he was regularly sent back to Abuja for hearings in which the judge seemed to side with the prosecutors. On May 17 — his 40th birthday — he attended another hearing, and his request for bail was ultimately denied. That evening, lawyers brought a large cake paid for by Binance to Kuje Prison, which he shared with his neighbors and guards.

Each night, Gambaryan would be locked into his cell early, often starting at 7 p.m., hours before the other prisoners, under the watchful eye of a guard who recorded his every movement in a notebook, all on the orders of the national security adviser. He found that he could exercise by doing pull-ups on the windowsill at the entrance to the quarantine courtyard. Despite the presence of giant cockroaches, geckos, and even scorpions in his cell—he learned to shake the small beige scorpions out of his shoes before putting them on—he slowly adapted to prison life.

Sometimes, he would wake from dreams in which he was still outside, suddenly realizing that he was in the small, filthy cell, and would then rise from his bed and anxiously pace the small space until the guards let him out around 6 a.m. Eventually, though, Gambaryan said his dreams became filled with prison imagery.

One afternoon in May, Gambaryan began to feel ill during a meeting with his lawyers. He returned to his cell, lay down, and spent the rest of the night vomiting. He thought he might have food poisoning, but guards ran a blood test that showed he had malaria. The guards demanded cash, which they used to buy an IV drip that they hung on a nail on the cell wall and gave him an anti-malarial shot.

The next morning, Gambaryan had a court hearing. He told the guards he was too weak to even walk, but they removed the IV and forced him into a car, saying they were following an official order. When he arrived at the courthouse, he struggled to climb the long steps, but once he entered the courtroom, his vision began to blur and the room began to spin. Then he fell to his knees. The guards helped him to his feet, and he slumped in his chair as his lawyers asked the court to order him to be taken to a hospital.

The judge issued a hospitalization order, but instead of being taken directly to a medical facility, Gambaryan was sent back to Kuje prison, where the court, his lawyers, the prison, the Office of the National Security Advisor, and the U.S. State Department discussed whether to temporarily release him because they were concerned that he was a flight risk. For the next 10 days, Gambaryan lay in his cell, unable to eat or stand up. He was eventually taken to Nizamiyeh Hospital in Abuja, where a chest X-ray was taken, antibiotics were prescribed after a brief examination, and the doctor said he was fine, then sent him back to Kuje prison without any explanation.

In fact, Gambaryan was even sicker than before. His friend, Turkish-Canadian Chagri Poyraz, eventually had to fly to Ankara to check Gambaryan's hospital records with the Turkish government, only to learn that his X-rays showed that he had multiple serious bacterial lung infections. Months later, the judge in the case also asked Abraham Ehizojie, the medical director at Kuje prison, to appear in court to explain why the hospitalization order was not followed. Prosecutors produced Gambaryan's medical records, saying he refused treatment and asked to be sent back to prison, but Gambaryan strongly denied this.

Back in his cell at Kuje prison, Gambaryan had a fever of 104 degrees Fahrenheit for several days. During his brief hospitalization, guards searched his cell and found his hidden cell phone, so he was completely isolated and unable to communicate with the outside world until his neighbors helped him get a new phone. He became weaker and weaker, and his breathing became labored, and his temperature did not drop. Gambaryan gradually felt that he might not survive. At one point, he called Will Frentzen and told him that he might be in critical condition. However, Kuje prison officials still refused to send him back to the hospital.

Despite this, Gambaryan didn’t die. But he stayed in bed for nearly a month until he was finally able to stand up and eat again. He weighed nearly 30 pounds less than when he was incarcerated.

One day, as he recovered in his cell, guards told him he had visitors. Although he still felt weak, he slowly walked to the office at the front of the prison. Once inside, he saw two members of the U.S. Congress, French Hill and Chrissy Houlahan, one from each party. Gambaryan could hardly believe they were real—the first Americans he had seen in months, aside from the occasional low-level State Department official who visited him.

For the next 25 minutes, they listened as Gambaryan described the horrible conditions in the prison and his close calls with malaria and later pneumonia. Hill recalled that Gambaryan spoke so softly that the two lawmakers had to lean in to hear him, especially over the noise of the fan.

At times, Gambaryan's eyes would fill with tears as the pain of loneliness and the fear of dying finally overwhelmed him. "He looked like a sick, weak, emotionally broken person who really needed a hug," Hill said. The two lawmakers each gave him a hug and said they would work for his release.

Then he was taken back to his cell.

The next day, June 20, Hill and Kolahan recorded a video on the tarmac at Abuja airport. "We have asked our embassy to promote Tigran's humanitarian release, given the poor conditions in prison, his innocence and his health," Hill told the camera. “We want him to come home, and we’ll leave the rest to Binance and the Nigerians.”

Connie Mack’s conversations with his old friends had an effect: During a subcommittee hearing on U.S. citizens detained by foreign governments, Rich McCormick, Gambaryan’s Georgia counterpart, suggested that Gambaryan’s case should be treated as a hostage case held by a foreign government. He cited the Levinson Act, which requires the U.S. government to assist citizens who have been wrongfully detained. “Was U.S. diplomatic intervention necessary to secure the release of the detainee? Absolutely, absolutely,” McCormick said at the hearing. “This guy deserves better.”

Meanwhile, 16 Republican lawmakers signed a letter asking the White House to treat Gambaryan’s case as a hostage case. A few weeks later, McCormick introduced the request as a congressional resolution. More than a hundred former federal agents and prosecutors also signed another letter asking the State Department to step up its efforts to help resolve the issue.

According to multiple sources, FBI Director Christopher Wray raised Gambaryan’s case during a meeting with President Tinubu during a visit to Nigeria in June. Nigeria’s tax authority, FIRS, has since dropped tax evasion charges against Gambaryan. However, more serious money laundering charges filed by the EFCC remain and still threaten him with decades of imprisonment.

For months, Gambaryan’s supporters had hoped that Nigeria would finally reach a deal with Binance and end his prosecution. However, Binance representatives said that by then, they seemed unable to come up with terms that would interest the Nigerian side, and the Nigerian side no longer even hinted at accepting any payment. Every time they felt they were close to a deal, the demands would change, the relevant officials would disappear, and the agreement would fall apart. “It’s like Lucy and the football,” said Deborah Curtis, an attorney at Arnold & Porter and a former deputy general counsel for the CIA, who was representing Binance at the time.

As the summer wore on, Gambaryan’s supporters began to believe that negotiations between Nigeria and Binance had hit a dead end and that the criminal case had not advanced far enough that Binance alone could not win Gambaryan’s freedom. “It started to become clear,” Frentzen said, “that this was only going to be solved through the U.S. government—otherwise there was no hope.”

Meanwhile, Gambaryan’s health was failing again. Spending long hours on a metal bed frame aggravated an old back injury he’d sustained while training at IRS-CI more than a decade earlier, which was later diagnosed as a herniated disk—a rupture in the outer layer of soft tissue between the vertebrae, causing the inner cushion to bulge out, compressing nerves and causing intense, persistent pain.

By August, Gambaryan told me in a text message, he was “almost paralyzed.” He hadn’t left his bed in weeks, and because of the lack of exercise, he was taking blood thinners to prevent blood clots in his legs. Each night, he wrote, the pain was too severe for him to sleep, and he often didn’t drift off until 5 or 6 in the morning, even when he couldn’t read. Occasionally, he would call his family and chat with his daughter while she played a Japanese role-playing game called Omori on a computer he had installed for her until she went to sleep in Atlanta. Then, a few hours later, he would drift off.

Despite visits from members of Congress and growing calls for his release, Gambaryan seemed almost desperate, at his lowest point in prison.

“I’m trying to be strong in front of Yuki and the kids, but it’s really bad,” he wrote me. “I’m really in a dark place right now.”

A few days later, a video appeared on X platform showing Gambaryan limping into the courtroom on crutches, dragging one foot. In the video, he asked a guard in the hallway for help, but the guard even refused his request. Gambaryan later told me that court staff had been instructed not to provide any help or let him use a wheelchair, fearing that this would arouse public sympathy.

“This is fucking terrible! Why can’t I use a wheelchair?” Gambaryan shouted angrily in the video. “I’m an innocent man!”

“I’m a fucking human being!” Gambaryan continued, his voice almost choking. He took a few steps with his crutches, shook his head in disbelief, and then leaned against the wall to rest. "I just can't."

If the directive was intended to prevent Gambaryan from eliciting sympathy when he entered the courtroom, it backfired. The video went viral and has been viewed millions of times.

By the fall of 2024, the U.S. government seemed to have finally reached a consensus that it was time for Gambaryan to come home. In September, the House Foreign Affairs Committee passed a bipartisan resolution approving McCormick's proposal to prioritize Gambaryan's case. "I urge the State Department, I urge President Biden: Put more pressure on the Nigerian government," said Congressman Hill at the hearing. "It must be recognized that an American citizen was kidnapped and held by a friendly country and had nothing to do with him."

Some of Gambaryan's supporters revealed that they heard that the new ambassador to Nigeria had also begun to frequently raise Gambaryan's situation with Nigerian officials and even President Tinubu, so much so that at least one minister blocked the ambassador on WhatsApp.

During the U.N. General Assembly in late September, the U.S. ambassador to the United Nations raised Gambaryan’s case during a meeting with Nigeria’s foreign minister and stressed the need for his immediate release, the minutes of the meeting said. Meanwhile, Binance hired a truck with a digital billboard to drive around the U.N. and midtown Manhattan, showing Gambaryan’s face and calling on Nigeria to stop unlawfully imprisoning him.

Meanwhile, White House National Security Advisor Jake Sullivan spoke by phone with Nigeria’s National Security Advisor Nuhu Ribadu, essentially demanding Gambaryan’s release, multiple sources involved in the push for Gambaryan’s release said. One of the most impactful news, several supporters said, was that U.S. officials made it clear that Gambaryan’s case would be an obstacle to talks between President Biden and Nigerian President Tinubu at the U.N. General Assembly or elsewhere, a news that deeply troubled the Nigerian side.

Despite all the pressure, the decision to release Gambaryan remains in the hands of the Nigerian government. “There came a time when the Nigerians realised that this was a very bad decision,” said a Gambaryan supporter who requested anonymity because of the sensitivity of the negotiations. “Then it became a question of whether they caved in or held on because of their pride or because they had reached the point of no return.”

On a long drive from Kuje to the court in Abuja one day in October — by then Gambaryan had lost count of how many court hearings he had been through — the driver received a phone call. He spoke for a while, then turned the car around and took Gambaryan back to the prison. Once there, he was taken to the front desk and told that he could not go to court because he was unwell. It was a statement, not an inquiry.

Back in his cell, Gambaryan called Will Frentzen, who told him that this might mean they were finally ready to send him home. After eight months of dashed hopes, Gambaryan didn’t take the news lightly.

A few days later, a court hearing was held without Gambaryan, and prosecutors told the judge that they were dropping all charges against him because of his health. Officials at Kuje Prison spent the day processing paperwork, then took him out of his cell, brought him the suitcase he had brought to Abuja, and drove him to the Abuja Continental Hotel. Binance booked a room for him, arranged for private security to guard him, and brought in a doctor to examine him and make sure he was healthy enough to fly. For Gambaryan, it all came so suddenly, and after so many months of hopeless waiting, it was almost hard to believe.

The next day, on the runway at Abuja airport, Nigerian officials handed him his passport back — after a dispute over a $2,000 fine he’d been charged for overstaying his visa. State Department agents helped him out of his wheelchair and onto a private plane equipped with medical equipment. Unbeknownst to Gambaryan, Binance staff had been planning the flight for weeks — Nigerian officials had told them he’d be released, then backtracked — and even arranged a route for him to fly over Niger, which had signed off on it less than an hour before takeoff.

On the plane, Gambaryan ate a few bites of salad, fell asleep on the sofa, and woke up in Rome.

Binance arranged a driver and private security to pick him up at the Italian airport and take him to the airport hotel for the night before flying back to Atlanta the next day. At the hotel, he called Yuki and then called Ogunjobi, his former friend in Nigeria and the person who persuaded him to return to Abuja a few months ago.

Gambaryan said he wanted to hear how Ogunjobi explained himself. While he was on the phone, Ogunjobi began to cry, apologize, and thank God that Gambaryan had finally been released.

It was all too much for Gambaryan, who listened quietly but did not accept the apology. As Ogunjobi was talking, he noticed a call from an American friend, a Secret Service agent he had worked with. Gambaryan didn't know it at the time, but the agent was in Rome for a meeting with his former boss, Jarod Koopman, the head of the IRS-CI cybercrime unit, and they were going to bring him beer and pizza.

Gambaryan told Ogunjobi that he had to hang up and ended the call.

On a cold and windy December day, former federal agents, prosecutors, State Department officials and congressional aides gathered in a plush room in the Rayburn House office building to talk. One by one, members of Congress walked in and shook hands with Tigran Gambaryan, who was wearing a dark blue suit and tie, with a neatly trimmed beard and shaved head. Although he had a slight limp from emergency spinal surgery he had in Georgia a month ago, his gait was firm.

Gambaryan took photos with each lawmaker, aide, and State Department official and spoke with them, thanking them for their efforts to bring him home. When French Congressman Hill said it was nice to see him again, Gambaryan quipped that he hoped he smelled better this time around than he did in Kuje.

The reception was just one of a series of VIP welcomes Gambaryan received upon his return. At the Georgia airport, Congressman McCormick came to greet him and presented him with an American flag that had flown over the Capitol the day before. The White House also released a statement saying that President Biden had called the Nigerian president to thank President Tinubu for facilitating Gambaryan's release on humanitarian grounds.

I later learned that the statement of thanks was part of an agreement between the U.S. government and Nigeria, which also included assisting Nigeria's investigation into Binance - an investigation that is still ongoing. Nigeria continues to prosecute Binance and Anjarwalla in absentia. In a statement, a Binance spokesperson said the company was "relieved and grateful" that Gambaryan had returned home safely and thanked everyone who worked for his release. "We are eager to put this incident behind us and continue working for a better future for the blockchain industry in Nigeria and around the world," the statement read. "We will continue to defend ourselves against these unfounded allegations." Nigerian government officials did not respond to WIRED's multiple requests for interviews about Gambaryan's case.

After the reception, Gambaryan and I took a taxi away, and I asked him what he planned to do next. He said he might return to government work if the new administration was willing to accept him—depending, of course, on whether Yuki would be willing to move back to Washington again. Cryptocurrency news site Coindesk reported last month that he had been recommended by some crypto industry figures with ties to President Trump for a senior position as the SEC's head of crypto assets or in the FBI's cyber division. Before considering this, he says vaguely, “I might need some time to gather my thoughts.”

I ask him how his experience in Nigeria has changed him. “It did make me angrier, I guess?” he replies with an oddly relaxed tone, as if he’s thinking about the question for the first time. “It made me want revenge on the people who did this to me.”

For Gambaryan, revenge may be more than just a fantasy. He is pursuing a human rights lawsuit against the Nigerian government, a case that began when he was detained, hoping to investigate the Nigerian officials who he believes held him hostage for the better part of a year. Sometimes, he said, he even texted the officers he held responsible, telling them, “You’ll see me again.” He said what they had done “brought shame to the badge” and that he could forgive them for what they had done to him, but not for what they had done to his family.

“Am I stupid for doing this? Maybe,” he told me in the taxi. “I was lying on the floor with a horrible backache, bored as hell.”

As we stepped out of the car and walked to his hotel in Arlington, Gambaryan lit a cigarette and I told him that, though he said he was angrier than before prison, he seemed calmer and happier to me than in years—I remembered him as an angry, driven man who was relentlessly pursuing his targets as I reported on his successive crackdowns on corrupt federal agents, cryptocurrency launderers, and child abusers.

Gambaryan responded that if he seemed more relaxed now, it was only because he was finally home—he was grateful to see his family and friends, to walk again, to be free from conflicts with forces larger than himself that had nothing to do with him. To have walked out of prison alive, not died there.

As for the anger-driven past, Gambaryan disagreed. "I'm not sure it was anger," he said. "It was justice. I wanted justice, and I still do."

Among his early NFTs, "Crossroad," a commentary on the 2020 U.S. presidential election, made headlines by selling for $6.6 million in February 2021.

Brian

BrianFTX clientele finds itself confronted by a deceptive priority withdrawal scam. These misleading emails purportedly originate from FTX Trading, West Realm Shires Services, and FTX EU.

Catherine

CatherineTech-driven compassion shows how Gitam BBDO's war room rescues hostages with innovation.

Hui Xin

Hui XinElon Musk's public scrutiny of Wikimedia Foundation's financial requests has generated considerable speculation, particularly regarding the prospect of a potential acquisition.

Kikyo

KikyoMagic Eden, a popular NFT marketplace on the Solana blockchain have decided to temporarily halt trading of Bitcoin BRC-20 assets on their platform

Aaron

AaronThe brief supports an appeal against the IRS that challenges government access to user transaction history on crypto platforms.

Alex

AlexThe new circular comes as Hong Kong embraces crypto but struggles with regulation.

Clement

ClementThe Attorney General alleges that these companies engaged in fraudulent activities and attempted to conceal losses amounting to over a billion dollars and lying to over 230,000 investors.

Clement

ClementRenowned author Robert Kiyosaki, famous for his book "Rich Dad Poor Dad," has shared his predictions on the future prices of Bitcoin, gold, and silver, alongside a stern warning concerning the risks associated with holding U.S. dollars, which he termed "fake money."

Jasper

JasperThese offerings, christened "Gas Station" and "Smart Contract Platform," promise to usher in an era of enhanced convenience and cost-efficiency.

Catherine

Catherine