AB DAO 官方 Twitter 账号升级,提醒社区注意风险

AB DAO 官方 Twitter 账号已完成升级,新账号 为:https://x.com/ABDAO_Global

Alex

Alex

Author: FinTax Carlton

As a major international financial center, Singapore has long attracted global capital and innovation with its open market environment, sound legal system, and efficient regulatory framework. In recent years, with the rapid development of digital assets and blockchain technology, the city-state has gradually become a key hub for crypto assets in the Asia-Pacific region. It not only attracts a large number of startups and international trading platforms, but also attracts institutional investors, technology developers, and policymakers exploring the future of digital finance. Driven by diverse market demand and proactive policy support, Singapore's crypto ecosystem is gradually maturing. According to the Independent Reserve Cryptocurrency Index (IRCI) Singapore 2025 report, cryptocurrency awareness in Singapore has reached an all-time high, with 94% of respondents knowing about at least one crypto-asset, 29% having owned crypto-assets, of which 68% of crypto investors hold Bitcoin, and 46% holding crypto-assets. 53% of crypto-asset holders have held or currently hold stablecoins, and their use in actual payments and cross-border transfers has reached 53%. Furthermore, 57% of crypto-asset holders believe the crypto industry will achieve mainstream adoption in the future, and 58% of the public call for clearer government regulation. These data collectively paint a picture of a market characterized by broad awareness, diverse applications, and clear expectations regarding regulation. Against this backdrop, understanding Singapore's cryptocurrency tax and regulatory framework is not only essential for legal compliance but also crucial for gaining insight into the market's development potential and risk landscape. This study will focus on two main areas: the underlying tax system and the regulatory framework, presenting the interplay between institutions and the market within Singapore's crypto ecosystem. This will provide investors with a clear picture of the current state of the industry, aiming to provide a reliable basis for business decision-making.

Cryptocurrency is often associated with the term "risk." Unlike most jurisdictions, such as the United States, where each state has unique cryptocurrency regulations, Singapore's cryptocurrency regulatory system is renowned for its clarity and balance. While obtaining relevant qualifications and licenses in Singapore is challenging for many Web3 companies, this fact significantly mitigates the risks faced by local Web3 companies. In Singapore, the tax and financial regulation of crypto assets are handled by the Inland Revenue Authority of Singapore (IRAS) and the Monetary Authority of Singapore (MAS), respectively. IRAS is primarily responsible for the tax administration of cryptocurrencies. As the national tax authority, IRAS formulates and implements policies related to income tax and goods and services tax (GST) for crypto assets, covering the tax obligations of businesses and individuals for various activities such as holding, trading, payment, and issuance. IRAS has published several dedicated e-Tax Guides, specifically addressing the income tax treatment of digital tokens and the GST treatment of digital payment tokens. These guides clarify the tax classification, taxable events, and tax calculation principles for different types of tokens (payment, utility, and security). IRAS is also leading the implementation of the Crypto-Asset Reporting Framework (CARF) in the country, playing a central role in cross-border tax information exchange. MAS primarily exercises financial regulatory authority over cryptocurrencies. As both a central bank and a comprehensive regulator of the financial industry and payment services, it has a significant impact on the licensing, compliance, and risk management of crypto-asset-related businesses. For example, MAS's licensing requirements for Digital Payment Token Service Providers (DPTSPs) and its regulatory framework for stablecoins will indirectly impact the tax treatment and compliance paths of related businesses.

Singapore's tax system is known for its simple structure and concentrated tax base. Its most prominent features are the absence of a global capital gains tax and the abolition of inheritance and gift taxes. This means that in Singapore, the appreciation of asset value itself does not generally constitute an independent tax event; whether it is taxed depends on the nature and frequency of the transaction. Coupled with Singapore's relatively low income tax rate, its tax system maintains stable fiscal revenue while remaining highly inclusive of capital flows and innovative activities.

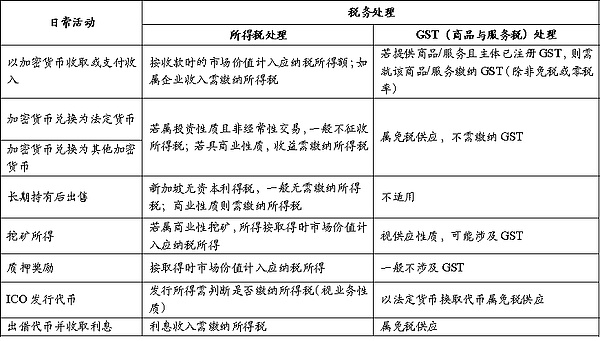

Within this institutional framework, Singapore's taxation of crypto assets is relatively concentrated, with the core two taxes being income tax and goods and services tax. The former focuses on taxing income from recurring or commercial crypto transactions, while the latter regulates the indirect tax treatment of digital payment tokens in the context of goods and services transactions. Other taxes, such as withholding tax and employment income tax, are only triggered under specific transaction structures or payment scenarios. (I) Income Tax Singapore's income tax system adopts the territorial source principle, taxing only income derived from Singapore and income remitted from overseas. Personal income tax follows a progressive tax rate system, with resident rates ranging from 0% to 22% (maximum 24% from the 2024 tax year). Non-residents are generally taxed at a flat 15% or the higher of the resident rate. Corporate income tax is a flat 17%, with tax exemptions for start-ups and specific industry deductions available. On April 17, 2020, IRAS issued the Income Tax Treatment of Digital Tokens, which aims to provide guidance on the income tax treatment of transactions involving digital tokens. The guidance classifies digital tokens into three categories: payment tokens, utility tokens, and security tokens. The Guidelines cover the following five categories of transactions:

i. Receipt of digital tokens as payment for goods and services;

ii. Receipt of digital tokens as remuneration for employment;

iii. Use of digital tokens as payment for goods and services;

iv. Buying or selling digital tokens; or

v. Issuing digital tokens through an Initial Coin Offering (ICO). 1. Tax Treatment of Payment Tokens Synonymous with cryptocurrencies, they have no other function besides payment. Although payment tokens are a form of payment, they do not qualify as legal tender because they are not issued by the government. For tax purposes, IRAS treats payment tokens as intangible property, which typically represents a set of rights and obligations. Transactions of goods or services using payment tokens are considered barter, and the value of the goods or services transferred should be determined at the time of the transaction.

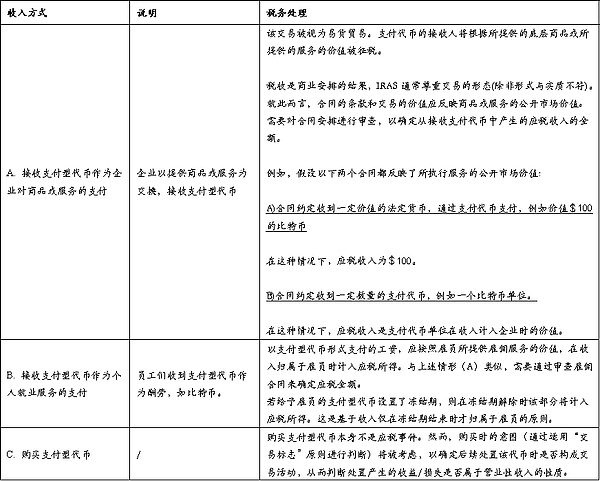

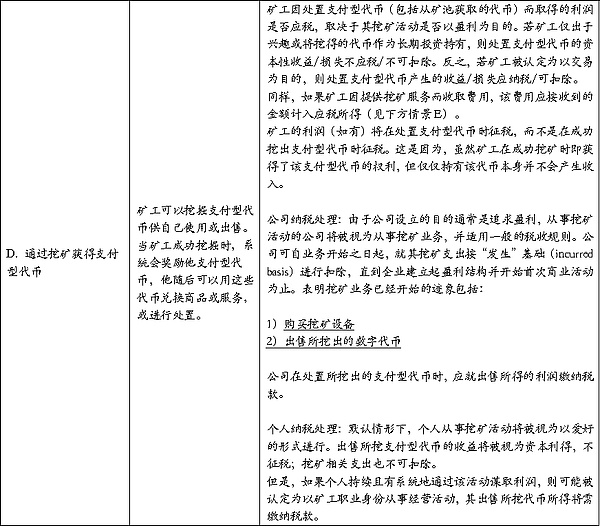

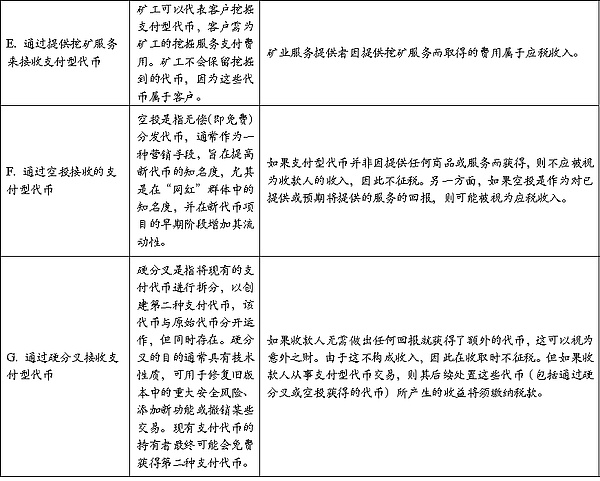

Table 1: Classification and tax treatment of payment tokens under income tax

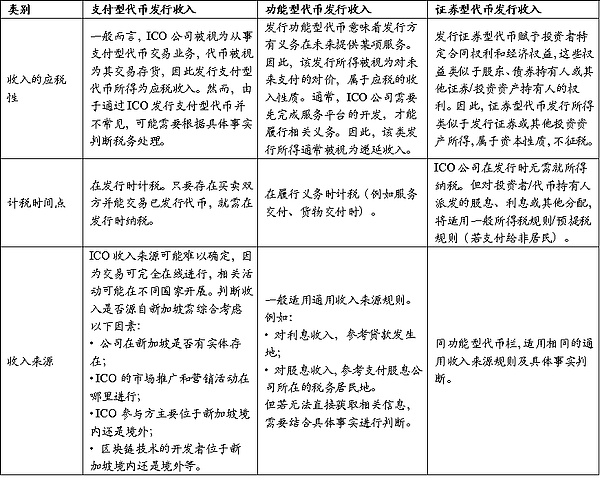

The taxability of ICO financing proceeds in the hands of the token issuer depends on the rights and functions attached to the tokens issued to investors:

Whether proceeds from the issuance of payment tokens are taxable depends on the specific facts and circumstances;

Proceeds from the issuance of utility tokens are generally treated as deferred income;

Proceeds from the issuance of security tokens are similar to proceeds from the issuance of securities or other investment assets/instruments. They are capital income in nature and are therefore not taxed.

For security tokens that pay interest, dividends or other distributions, the deductibility of such payments on the issuer shall be governed by Sections 14 and 15 of the Income Tax Act.

See Table 3 for details.

In addition, you may face the following special circumstances:

Failed ICO: If a company issues utility tokens through an ICO and uses the raised funds to develop a platform or service, but ultimately fails to deliver, the tax treatment will depend on the destination of the funds. If the raised funds are returned to investors, the company does not need to pay tax on the refunded amount. If the funds are not returned, the nature of the ICO will need to determine whether it is a capital transaction or a profit transaction. The tax authorities will comprehensively consider factors such as the company's main business, the reason for issuing the tokens, and its contractual obligations.

Preliminary Expenses: Reasonable business expenses incurred by a company conducting an ICO before formal operations can be claimed according to the current pre-operational expense deduction rules. Under Section 14U of the Income Tax Act, qualifying expenses can be deducted in the pre-commencement basis period, and unutilized losses can be carried forward to future years or used through group relief. This provision helps reduce the tax burden on businesses during their early stages. Founder Tokens: ICO companies may reserve a portion of their tokens for founding developers as a reward for their contributions to the token's design and implementation. If these "founder tokens" are issued as compensation for services rendered, they are taxable income and taxed when the founders actually acquire control. If there is a lock-up or restriction period, the value at that time is taxable upon expiration. If the tokens are not received for services rendered, they are not taxable income. Tip: The Inland Revenue Authority of Singapore (IRAS) explicitly requires taxpayers to maintain complete records of transactions related to digital tokens and to make them available upon request. These records should include transaction dates, the number of tokens received or sold, the token value and exchange rate at the time of the transaction, the purpose of the transaction, customer or supplier information (for buy/sell transactions), ICO details, and receipts or invoices for business expenses. This information is not only the basis for tax filings but also crucial evidence for responding to tax audits and ensuring compliance.

Table 3: Taxability of different types of token ICOs

Goods and Services Tax (GST) is the main form of indirect tax implemented in Singapore since 1994. In a broad sense, it falls under the category of Consumption Tax as it is a tax levied on final consumption. However, it is essentially still a Value Added Tax (VAT) levied at a uniform rate on the supply of most goods and services and imported goods. The standard GST rate is 9% until 2024. GST is collected and paid by businesses and applies to domestic transactions and cross-border digital services. Certain financial services, exports, and certain international services are exempt or zero-rated. On August 3, 2022, IRAS released the new GST: Digital Payment Tokens (originally drafted on November 19, 2019), which regulates the GST treatment of transactions involving digital tokens and cryptocurrencies (hereinafter referred to as digital payment tokens). The core change is that, effective January 1, 2020, the supply of qualifying digital payment tokens (DPTs) will be GST-exempt, avoiding double taxation on the purchase and use of tokens. This adjustment significantly reduces tax friction in cryptocurrency payments and transactions, enhancing Singapore's competitiveness as a crypto-friendly jurisdiction. However, it's important to note that this tax exemption is limited to cases that meet the definition of a DPT and does not affect the normal collection of taxable items such as intermediary service fees and platform fees. In the specific rules, IRAS first strictly defines a DPT and clarifies the types of tokens that are not exempt (such as utility tokens, security tokens, and closed-end virtual currencies). The guidelines then differentiate between different types of tokens and their GST treatment in transactions, exchanges, and payments. For example, the purchase, sale, exchange, and payment of compliant DPTs are tax-exempt, but related services provided by platform operators, wallet custodians, and payment intermediaries will still be subject to GST taxable supplies. By using this dual approach of "asset attributes + business type," Singapore maintains a fair tax system while minimizing tax barriers to crypto transactions. 1. Classification of Digital Payment Tokens The Guidelines stipulate that a digital payment token (DPT) is a digital representation of value that has all of the following characteristics: (a) expressed in the form of units; (b) fungible by design; (c) not denominated in any currency and not pegged to any currency by the issuer; (d) can be transferred, stored or traded electronically; (e) is, or is intended to become, a medium of exchange acceptable to the public or a section of the public without significant restrictions on its use as consideration.

However, digital payment tokens do not include the following:

(f) legal tender;

(g) a supply that is treated as an exempt supply under Part I of Fourth Schedule to the Goods and Services Tax Act, other than because it is a digital payment token having the characteristics of (a) to (e) above, is not a digital payment token;

(h) anything that confers a right to receive or instruct a particular person or group of persons to provide goods or services and which ceases to serve as a medium of exchange after the right is exercised. IRAS lists typical DPTs, including Bitcoin, Ethereum, Litecoin, Dash, Monero, Ripple, and Zcash. These tokens all possess core characteristics such as homogeneity, non-pegged to any fiat currency, electronic transferability, and serving as a publicly recognized medium of exchange. Furthermore, tokens like IdealCoin, which can be used for payment within a specific smart contract framework but can also be used freely outside of that framework, and tokens like StoreX, which can continue to circulate as a means of payment even after certain specific rights have been exercised, also meet the definition of a DPT. In contrast, examples that do not qualify as DPTs include: stablecoins, which do not meet the requirements of homogenization and non-pegging because their value is anchored to fiat currency; virtual collectibles such as CryptoKitties, which lack fungibility due to their lack of complete interchangeability; game points or virtual currencies that are limited to specific environments; and points or loyalty points issued by retailers or platforms that can only be redeemed for specific goods or services. These tokens cannot serve as a medium of exchange for the general public. Some other examples, while initially similar to DPTs, are excluded under certain conditions. For example, the StoreY token was originally designed as the sole means of payment for distributed file storage services. However, after users exercised their rights, the token ceased to function as a medium of exchange and therefore no longer met the definition of a DPT.

For more detailed rules, characteristics and case studies, please refer to Section 5 of the Guidelines (especially paragraphs 5.2–5.13 and the examples).

2. General Rules for Digital Payment Token Transactions

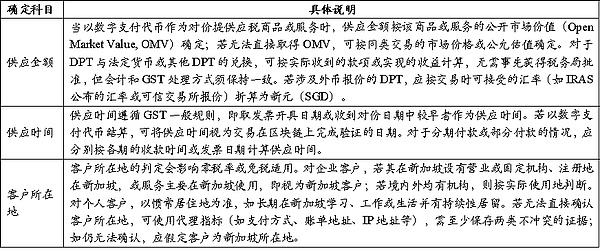

When DPT is used as a means of payment for goods or services (but not including exchange into legal tender or other DPT), the payment itself is not considered a supply and therefore not subject to GST. The payer does not need to pay GST when paying with DPT, but if the payee is registered for GST, it should calculate output tax on the goods or services it provides, unless the supply is exempt, zero-rated or not subject to tax. For example, if GST-registered company A purchases software with Bitcoin, A is not required to pay GST on the transferred Bitcoin. However, if the seller, Company B, is a GST-registered entity, it must account for GST on the supply of the software. Furthermore, the exchange of DPTs for fiat currency, as well as the exchange of one DPT for another, are both exempt supplies and are not subject to GST. However, businesses must still classify the transactions as exempt supplies when filing their returns and report the net realized gain or loss. For example, if Company C exchanges Bitcoin for Ethereum, neither party is required to pay GST; it should be treated as an exempt supply on the return. Furthermore, if a GST-registered company issues DPTs through an initial coin offering (ICO) and exchanges them for fiat currency, the proceeds from the issuance are also considered exempt supplies and should be reported as exempt income on the GST return. For example, if Company E issues DPTs and sells them to the public in Singapore dollars, the proceeds are reported as exempt supply income. Finally, loans, advances, or credit arrangements involving DPTs are also exempt supplies, and the related interest income is not subject to GST, but must be reported as exempt income in the return. For example, if Company F lends DPTs and receives interest, the interest is reported as exempt supply in the GST return. Table 4 illustrates the specific rules for determining the amount of supply, the time of supply, and the location of the customer in transactions involving digital payment tokens.

Table 4: Determination of each accounting item

3. Rules for specific business scenarios

(1) Mining

In the general mining process, miners provide computing power or verification services to the blockchain network, but have no direct relationship with the transaction parties being served, and the party that issues block rewards/mining fees cannot be identified. Therefore, obtaining digital payment tokens generated by mining (such as block rewards) does not constitute a "supply" under the GST, and GST is not levied on such acquisition. However, if a miner provides paid services to an identifiable counterparty (such as agreed-upon commissions, transaction fees, computing power rental fees, etc.), this constitutes a taxable supply of services. If the miner is a GST-registered person, tax should be calculated and reported at the standard rate; zero-rating treatment is only available if the conditions for zero-rating are met. If the jurisdiction of the counterparty cannot be reasonably determined, the standard rate should be applied.

Subsequent disposal of mined tokens: From January 1, 2020, miners selling or transferring mined digital payment tokens to customers in Singapore are tax-free supplies; if miners use the mined tokens to purchase goods or services, they are not considered to be "supplying tokens" and do not need to calculate tax on the token portion (the supplier of goods/services still calculates tax according to its own rules).

(2) Intermediaries

Services related to digital payment tokens provided by intermediaries are still taxable supplies even if token transactions are involved. If the intermediary is registered for GST, whether it needs to report token sales in the GST return depends on whether it acts as a "principal" or "agent" in the transaction. If you sell tokens as a principal, you need to report the sale as your own supply to GST; if you sell tokens on behalf of a client as an agent, you should not include the sales as your own supply, but only the fees or price difference collected in the transaction should be included as supply and report GST (unless the supply is subject to zero tax rate). When judging its own status, intermediaries should conduct self-assessment based on indicators such as contractual responsibilities and risk assumption, payment obligations, price determination power and token ownership.

(3) Rules for handling input tax deductions and reverse charges

In the course of business operations, an enterprise can only apply for input tax deductions for expenditures used for taxable supplies; if the expenditure is used for tax-exempt supplies (such as exchanging digital payment tokens for legal currency or other tokens), it cannot be deducted. If the expenditure involves both taxable and tax-exempt supplies, or involves the overall operation of the enterprise, it needs to be allocated in proportion. For businesses that make both taxable and exempt supplies (e.g., some of their business involves the exchange of digital payment tokens), they should allocate and attribute input tax in the same manner as other partially exempt businesses, unless they meet the De Minimis Rule and, if applicable, can treat the supply of digital payment tokens as incidental exempt supplies. Finally, as partially exempt businesses, if they obtain services or low-value goods from overseas suppliers, they may still be subject to reverse charge obligations and should refer to the relevant guidance from the Singapore Inland Revenue Authority of Singapore.

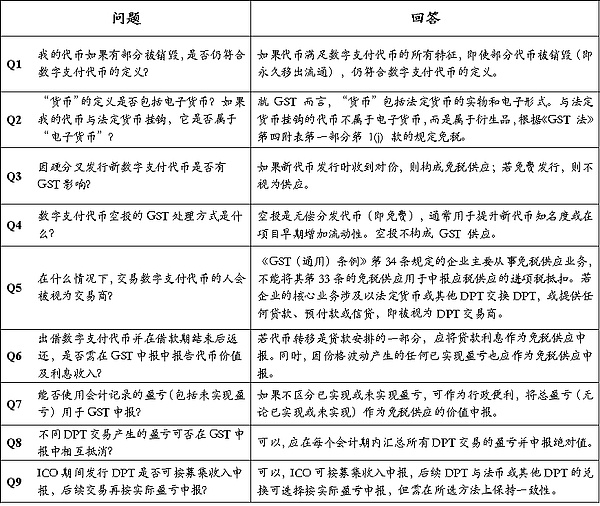

4. Frequently Asked Questions

Table 5: Common Q&A

AB DAO 官方 Twitter 账号已完成升级,新账号 为:https://x.com/ABDAO_Global

Alex

AlexArweave, Arweave's working principle and significance of existence Golden Finance, this article briefly introduces Arweave's working principle and value.

JinseFinance

JinseFinanceThe U.S. economy declined more than expected, global liquidity tightened more than expected, domestic industrial policies were not implemented as expected, the "black swan" event before the U.S. election had an impact, and expectations of global geopolitical turmoil rose more than expected.

JinseFinance

JinseFinanceThe S&P 500 (an index of the top 500 US companies) is still below its mid-July peak and the level at the end of July when the “crash” began. What is causing this downward trend? Does it portend more serious problems for the US economy?

JinseFinance

JinseFinanceOn August 8, the U.S. Federal Reserve took a major enforcement action against Pennsylvania-based Customers Bank, marking the U.S. government’s gradual increase in regulatory oversight of cryptocurrency-related businesses.

JinseFinance

JinseFinance JinseFinance

JinseFinance JinseFinance

JinseFinanceArmstrong rowed back on a suggestion he made last month that the company may be forced to move its headquarters overseas.

Others

OthersThe Ethereum Foundation's Danny Ryan discusses how the Merge will increase security and explains how proof of stake impacts developers.

Future

FutureNigel Dobson, head of portfolio banking services at ANZ, said: "When we looked at this in depth, we came to the conclusion that this is a significant protocol shift in financial market infrastructure."

Cointelegraph

Cointelegraph