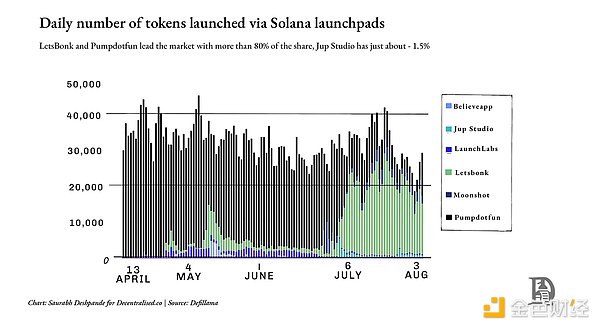

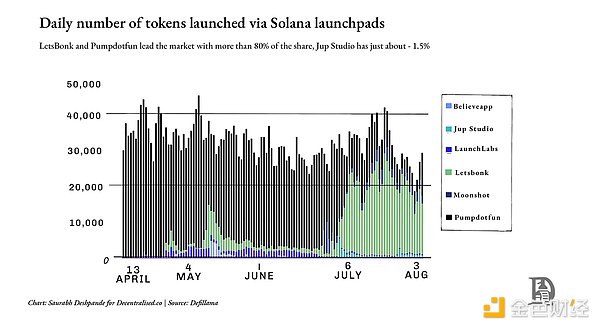

Is your supply sufficiently unique or easily interchangeable to prevent it from being "captured" by a single supplier? Is your marginal cost of introducing new supply zero or extremely low? Does the larger the scale, the stronger the model? If any of these three conditions are not true, you are not an aggregator—you are just a middleman who can be easily replaced. When "Liquidity" Becomes a Moat In the crypto space, different projects may have different types of "moats." Some rely on regulatory compliance and trust to build their brand, such as USDC, which has won the market with its transparency and compliance. Some rely on technological advantages to build barriers, such as Starkware's zero-knowledge proof system or Solana's parallel execution. Some rely on community and network effects, such as Farcaster's user graph. But the most insurmountable moat, and the one most often found in leading projects, is liquidity. Of course, "getting liquidity right" is crucial. Liquidity isn't loyal—if the incentive is strong enough, it will move. For example, in 2020, the Sushiswap "bloodsucking attack" drained over $1 billion in liquidity from Uniswap in just a few days by offering higher mining rewards. The lesson is simple: liquidity only sticks when leaving is more painful than staying. I've written before about Hyperliquid, which precisely understands this logic. It built the deepest perpetual contract order book among decentralized exchanges (DEXs), but it goes beyond that—it allows other applications and wallets to directly access its liquidity. For example, the Phantom wallet can access Hyperliquid's order flow, providing users with tight bid-ask spreads without having to build their own marketplace. In this relationship, it's the aggregator that needs the supplier, not the other way around. Once users and applications default to routing through you, you're no longer just another trading venue—you become the platform that can't be bypassed. As of last month, Hyperliquid's order book had processed over $13 billion in external trading volume; Phantom routed $3 billion of that volume, earning over $1.5 million in fees alone. This demonstrates that Hyperliquid's network effect is exploding. Liquidity refers to the ability to quickly exchange one asset for another without causing significant price fluctuations. In traditional finance and DeFi, deep liquidity means cheaper transactions, safer borrowing, and more stable derivatives markets. Without liquidity, even the most cleverly designed protocols can become ghost towns. Once liquidity is established, it tends to accumulate: traders and applications automatically flock to deep pools, which bring tighter spreads and higher transaction efficiency, attracting even more liquidity—a positive cycle. This is precisely why Aave maintains its leading position in a multi-chain world. With large lending pools across multiple assets, Aave is the preferred choice for borrowers seeking scale and security. As of August 6th, Aave's cross-chain total locked value (TVL) exceeded $24 billion. Over the past 12 months, borrowers paid $640 million in interest fees, and the platform generated approximately $110 million in revenue. A similar logic applies to Jupiter, the aggregator on Solana. On Ethereum, Uniswap already aggregates the majority of spot liquidity, so aggregators like 1inch can only offer marginal improvements. In the Solana ecosystem, liquidity is fragmented across Orca, Raydium, Serum, and other smaller platforms. Jupiter consolidates these into a single aggregation layer, consistently providing the best prices. At one point, Jupiter accounted for half of the Solana network's computing resources, demonstrating its significant impact on liquidity routing across the ecosystem—a downtime would degrade trade execution quality across the entire network. If you consider liquidity as the core resource Jupiter is aggregating, its product decisions become readily understood: launching a mobile app, expanding into new trading and lending products, acquiring other protocols... all with a single goal: to secure more order flow, lock in liquidity paths, and strengthen its platform position. Jupiter's growth path exemplifies the classic "stair-climbing" model for aggregators in DeFi: from a small tool that "helps you find the best spot trading," it evolved into the default liquidity portal on Solana, and further expanded into products attracting diverse types of liquidity. Its gradual ascent, and how each stage feeds back into the next, is a near-living rendition of Ben Thompson and Aswath Damodaran's Aggregation Theory. Three Core Questions of Aggregation: These three questions, posed by Ben Thompson, serve as a quick checklist for determining whether an aggregator has taken off. 1. What is the core advantage of the current leading players? Can it be digitized? In DeFi, this key advantage is liquidity. Whoever owns a deeper pool can offer tighter bid-ask spreads and a more secure lending and borrowing environment. Liquidity itself is a digital asset, easily accessible, comparable, and routed—perfectly suited for aggregation. 2. Once key advantages are digitized, does competition shift to user experience? Once liquidity is accessible to everyone, competition becomes a contest of execution quality: faster settlement, better routing, and fewer trade failures. This is where products like BasedApp and Lootbase come into play. BasedApp packages DeFi primitives into a smooth, native mobile experience, simplifying operational complexity for the average user. Lootbase, on the other hand, brings Hyperliquid's rich perpetual contract liquidity to mobile devices—allowing users to easily trade perpetual contracts on mobile with low latency while still enjoying the full functionality of Hyperliquid's backend. Both embody the same principle: once liquidity is open and digitized, user experience becomes paramount. 3. If you win the user experience, can you establish a positive cycle? Users come to you for better prices, attracting more liquidity; more liquidity further enhances trading price advantages; trading habits and system integration make liquidity extremely sticky. The ultimate goal is to become the starting point of the entire market. If suppliers cannot afford not listing, you can charge for listing; in the DeFi world, you can even control the entire order flow. Layer 1: Price Discovery This is the most basic aggregation function—telling users where to find the best prices. Kayak compares flight prices, and Trivago compares hotels. In the crypto space, early DEX aggregators like 1inch and Matcha operate at this layer. They scan all available liquidity pools, displaying the best prices, and users can click to trade. The same is true of DeFiLlama's Swap feature: it integrates multiple aggregators with native AMMs to provide users with quote options. However, the barriers to entry at this level are very low. If the underlying market is already highly concentrated (such as spot trading on Uniswap on Ethereum), the marginal returns from aggregation are minimal, and users can simply bypass you and trade on the original platform. You're helping, but you're not required to. The Second Layer: Trade Execution: At this layer, you no longer just tell users where to go; you help them complete the transaction. Amazon's "Buy with One Click" button is a classic example: the system finds the cheapest option and completes the order using your account information. In DeFi, Aave occupies this layer. When a user initiates a loan, the required liquidity is already locked in Aave's contracts. Execution creates stickiness because transaction outcomes are directly tied to your platform. You, not the market, are responsible for the quality of the user experience (whether it's an instant transaction or a failed transaction). The key to this layer is that you become the starting point for transactions. Google is the starting point for web content, and the App Store is the starting point for mobile apps. In crypto, the built-in Swap function in a wallet is the entry point for some users—they both begin and end there. On Solana, Jupiter has reached this level. It starts as a price discovery tool, advances to the execution layer through its intelligent routing system, and then, through integration with front-ends like Phantom and Drift, becomes the default path for users' transactions. Even if users don't visit the jup.ag website, a significant number of transactions on Solana are routed through Jupiter. This is distribution control: if the supply side wants to reach users, they must go through you. The "Climbing Challenge" in DeFi: The biggest problem in DeFi is the rapid movement of liquidity; even the slightest incentive can drain the pool overnight. Therefore, climbing from Layer 1 to Layer 3 isn't a matter of "first come, first served" but rather who can consistently convince users and order flow to choose you, even if newcomers imitate your features. On Ethereum, 1inch largely remains on Layer 2 because Uniswap already aggregates most of the liquidity, and the marginal improvements provided by aggregators are very limited. Many users simply skip 1inch transactions. Add to that competitors like CowSwap and KyberSwap, and the market is further fragmented. In contrast, Aave's stability stems from its control over transaction execution in its own vertical, making it its own infrastructure. Jupiter's advantage over Solana lies in its sequential completion of three layers. Solana's liquidity is decentralized → the price discovery layer has real value, intelligent routing optimizes transactions → enters the execution layer, integrates with wallets and dApps → reaches the distribution control layer. At one stage, half of the Solana network's computing resources came from Jupiter-related transactions, as both users (demand) and liquidity pools (supply) rely on Jupiter. Once the third layer is reached, the problem changes. The question is no longer, "How do we acquire more users?" but, "What else can we operate with this distribution model?" Amazon started with books and eventually sold nearly everything. Google started with search and eventually expanded to maps, email, and cloud computing. For Jupiter, the distribution model is order flow. The obvious next step is to add more products that leverage the same liquidity relationships, such as perpetual bonds, loans, and portfolio tracking. The bigger option here is Jupnet. Solana has yet to achieve the specialized throughput and execution capabilities of platforms like Hyperliquid, which were designed from the outset with financial-grade latency and determinism as their goals. These qualities are critical to scaling a full financial stack to real-world scale. The easier option would be to launch these products on a chain that already has these guarantees. Instead, Jupiter chose the more difficult route, building Jupnet as an application-controlled, low-latency execution layer designed to run alongside Solana. Jupnet is intended to serve as shared infrastructure within the Solana ecosystem. It will serve as a layer that enables traders, RFQ systems, batch auctions, and other latency-sensitive processes to execute precisely and ultimately settle natively on Solana. If successful, it will keep users and assets on Solana while providing the speed and finality expected of a vertically integrated platform. This aims to bridge the gap between general-purpose blockchain throughput and the micro-latency requirements of global finance, while avoiding the fragmentation of cross-chain liquidity. But it's important to look at the bigger picture. While Jupiter may be dominant within Solana, it still faces stiff competition at an industry level. In the broader cross-chain space, 1inch, CoWSwap, and OKX Swap remain significant competitors. By 2025, Jupiter will average approximately 55% market share among the top five DEX aggregators, but this figure will fluctuate based on on-chain activity and integrations. The chart below illustrates how fragmented the aggregation layer outside of Solana remains. At this stage, Jupiter has undoubtedly become an aggregator within the Solana ecosystem. The flywheel has begun to turn: more traders → more liquidity → better execution → attracting more traders. At this point, you're more than just a liquidity aggregator; you're the "shelf," the "habit," the "starting point of the market." However, maintaining this position isn't automatic. So, when liquidity itself is no longer sufficient, how can Jupiter grow? Jupiter's answer: Acquire entrepreneurial teams that already have access to new types of user traffic and bring that traffic into its own ecosystem. M&A as a Growth Engine A few months ago, I wrote two articles on fundamental themes about how companies scale. The first is the nature of compounding innovation and how companies can use M&A to accelerate this compounding growth. The first is to consolidate existing advantages so that each new product, feature, or capability benefits from all the advantages that came before it. The second is to recognize when acquiring, rather than building, is the fastest way to increase those advantages. Jupiter's evolution bears traces of both. Its M&A strategy is rooted in finding teams led by truly influential founders and integrating them into distribution networks to amplify their impact. The company seeks teams with deep expertise in their respective verticals, enabling Jupiter to expand its reach without slowing down its core roadmap. Moonshot provides a token launch platform for projects looking to increase liquidity, translating the creation of new tokens into direct redemption and trading activity on Jupiter. DRiP adds a community-driven NFT minting and distribution platform, capturing attention from audiences beyond the trading interface and converting it into on-chain activity. The acquisition of Portfolio provides Jupiter with a suite of tools for active traders to manage their positions, enhancing everyday engagement. Jupiter could have built these features in-house at a lower cost, but this is about founder recruitment, not just the features themselves. However, growth in some of these metrics has yet to materialize. Take the token issuance platform (Launchpad) as an example. Market leaders Pumpdotfun and LetsBonk control over 80% of daily token issuance, while Jup Studio and Moonshot have a combined market share of less than 10%. The chart below illustrates the dominance of the incumbent giants. In this case, the default model may be entrenched, and if Jupiter wants to break out of this situation, it may require a radically different strategy.

Founder-led M&A as a multiplier

Once you control the "shelf," the way to expand it is to bring in operators who already have a foothold in a certain part of the market you want to serve. Jupiter's screening criteria is: Does the team bring some kind of new type of liquidity or users that can enhance the flywheel effect? In this respect, the logic is reminiscent of Amazon's early flywheel model—each new product category or supplier represents an expansion of choice, improving the user experience, driving more traffic, and ultimately attracting more suppliers. For Jupiter, each acquisition is like adding a new aisle to its store, broadening the selection and deepening the reasons why traders and liquidity providers choose it as a starting point. In this process, the founders' energy itself becomes a breakthrough. By acquiring teams with strong founding DNA, Jupiter can enter unfamiliar territory, such as the NFT culture through DRiP and the mass token issuance market through Moonshot, without diluting its core focus. These founders possess deep expertise in their respective sectors, command a trusted community, and can move quickly. By connecting them to Jupiter's distribution channels, their influence can be amplified overnight, and Jupiter gains new users and liquidity. These acquisitions clearly demonstrate: Moonshot is a token issuance and trading channel designed for mainstream user behavior, allowing newly issued tokens to seamlessly access Jupiter's swap, financing market, and perpetual contract system—all without leaving the Jupiter ecosystem. DRiP is an NFT minting and distribution channel for creators, attracting communities that might not otherwise actively use the swap interface, converting their attention into on-chain activity. Moonshot attracted over 250,000 users and exceeded $1.5 billion in trading volume within three days of $TRUMP's launch. DRiP has attracted over 2 million collectors, minted over 200 million items, and facilitated over 6 million secondary sales. The integration process follows a clear path: the founders retain control of their product direction. From day one, their products are integrated into Jupiter's front-end and back-end systems, immediately leveraging its user base, while Jupiter gains new user flow. Each acquisition adds a unique liquidity primitive, such as issuance, culture, and leverage, rather than duplicating existing ones. The core identity remains unchanged: all paths ultimately lead to Jupiter. In DeFi, code can be forked overnight, but the "market origin" is not so easily replicated. Founder-led acquisitions allow Jupiter to add new entry points without losing its central role as a hub for user engagement, making its flywheel even harder to replicate. As its app-controlled execution and low-latency infrastructure mature, Jupiter is likely to acquire teams with execution primitives, such as risk control engines, matching layers, and professional trading platforms, and integrate them into Jupiter. Aggregators vs. Providers: Looking further ahead, two dominant models are emerging in DeFi: Jupiter and Hyperliquid. Both are highly capable, but their strategies differ significantly. Hyperliquid's goal is to control liquidity. It doesn't prioritize directly owning end-user relationships, but instead offers a "liquidity-as-a-service" offering. If you can build a better user experience, you can definitely use Hyperliquid's order book and execution engine. This is the idea of "Builder Codes"—it allows others to own the front-end experience, while Hyperliquid quietly supports the back-end. This is a model centered on the "supply side." Jupiter, on the other hand, focuses on distribution. It controls the interface, the shelf, the entry point for the market. Its strategy is to aggregate fragmented market liquidity and become the default entry point. It attracts liquidity and then allocates it. This means controlling user relationships, not just execution channels. From perpetual swaps to portfolios, Jupiter is trying to bring every financial interface into its orbit. But perpetual swaps perhaps best illustrate the limitations of this approach—at least at this stage. While Jupiter has made some breakthroughs on Solana, Hyperliquid remains far ahead globally, holding approximately 75% of the perp DEX market share. The chart below demonstrates Hyperliquid's overwhelming advantage in trading volume. Both models essentially bet on scale, but their driving forces are completely different: Jupiter's logic is: liquidity follows the user interface. Hyperliquid's logic is: Liquidity itself is the user interface. Jupiter is building the "entry point"; Hyperliquid is building the "end point layer." In reality, we're witnessing a divergence: if you seek broad user coverage and cohesiveness, you'll choose Jupiter. If you seek depth, certainty, and composability, you'll choose Hyperliquid. One transforms liquidity into a dependency network, while the other becomes the underlying layer upon which everyone builds. The ultimate winner won't be determined by who reaches the end point first, but by who becomes irreplaceable. This is one of the reasons DeFi is so exciting right now—for the first time, we're witnessing a head-on clash between two philosophies. One says distribution is the moat; the other says liquidity is. Applications are becoming the new platforms. When Ethereum's Layer 2 (L2) platforms first emerged, hopes were high that they would become the new platform—perhaps a neutral space where applications could freely combine, compete, and scale. The reality is, however, that most L2s have failed to become the platforms we envisioned. They remain primarily "infrastructure": providing speed, security, and scalability, but lacking a grasp on the user relationship. A true "platform" is the starting point of the user journey. It's where demand aggregates, habits form, and distribution occurs. Few L2s have reached this level. Most are more like pipes than shelves. Few L2s have established meaningful distribution systems, and even fewer have become the default starting point for users. Instead, applications like Jupiter and Hyperliquid are beginning to exhibit the characteristics of platforms. They master user relationships, become ingrained in users' daily habits, and continue to strengthen this position through acquisitions or integrations with other applications. They are beginning to resemble more and more Web2 platforms. Google is more than just a search engine. It acquired YouTube, transforming its search dominance into video dominance. Facebook, in turn, expanded its dominance of the attention market by acquiring Instagram and WhatsApp. They share a common strategy: entering adjacent sectors where they haven't yet captured a significant portion of the market but where users are already active, and acquiring the dominant players in those sectors. YouTube was already a dominant force in online video; WhatsApp dominated mobile communications. Once acquired, Google and Facebook's distribution flywheels could immediately accelerate these products, ultimately achieving a complete command of user attention and consolidating their dominance.

Jupiter is following the same path. Launchpad, NFT minting tools, portfolio managers, and the upcoming Jupnet—all share the common goal of expanding touchpoints, capturing more user behavior, and channeling more liquidity into their systems. Their strategic objective is to become the "shelf"—the default entry point—the starting point for financial interactions. But aggregation doesn't guarantee success. History is littered with examples of failed platform acquisitions or aggregations. The root cause of these failures lies in a failure to understand user relationships or a miscalculation of the mechanisms that shape user behavior. Take, for example, Microsoft's acquisition of Nokia. It was a gamble intended to control mobile distribution. But users had already migrated to iOS and Android. Although Microsoft controlled both hardware and operating systems, its offerings, both hardware and software, were largely indistinguishable from existing user choices or lacked sufficient appeal to encourage migration. It lacked control over the application layer, earned developer loyalty, and persuaded users to change their habits. Lacking control over supply and differentiation, this "shelf" ultimately fell by the wayside. Another example is Google's $12.5 billion acquisition of Motorola. While seemingly gaining control of phone manufacturing capabilities, it didn't change how users used Android. A few years later, Google sold it to Lenovo for $2.9 billion. Control over the supply side doesn't translate into control over the demand side. Yahoo's $1.1 billion acquisition of Tumblr is another example. Tumblr was once a cultural phenomenon, but Yahoo misjudged its user base and prematurely pursued monetization. It seemed like a distribution asset, but ultimately, product changes and review policies led to user churn, turning it into a negative asset. These cases reveal a core truth: M&A alone doesn't create a flywheel. If you're not your users' starting point, their habits, or their interface, then no matter how many features you bundle, users won't follow you. This is what's so interesting about the current DeFi world. Jupiter is acquiring frontends, distribution channels, and liquidity primitives, striving to become the default starting point for the Solana financial system. Hyperliquid is taking the opposite approach: focusing on depth rather than breadth, building the underlying system that others can build around. In other words, the "platform wars" we're witnessing aren't chains versus chains, but rather applications that act like platforms. This raises a larger question: If L2 itself doesn't control distribution, how does value accrue when applications do? Does the logic of the FAT protocol still hold? We end with some unanswered questions, and this openness is intentional. This landscape is still undetermined. We will return with sharper judgments, more data, and more stories and analogies to help us understand this evolution.

Catherine

Catherine