Author: David C. Source: Bankless Translation: Shan Ouba, Golden Finance

Last week, trader James Wynn lost $100 million in liquidation on Hyperliquid.

The losses included 949 bitcoins (about $99.3 million) and 982.5 million kPEPE (about $11.6 million), which triggered liquidation of his 40x leveraged position after Bitcoin fell below $105,000. But the wonderful thing is that Wynn claimed that he was not just "bad luck", but "hunted."

Wynn wrote on social media: "I at least exposed how corrupt these markets are." He believes that someone deliberately planned a "liquidation hunt" to trigger his highly leveraged position by lowering the price, and then quickly let the market rebound.

Whether the allegation is true or not, the incident does expose a significant loophole in decentralized trading: everyone's positions are public. Just like showing your cards to everyone when playing poker.

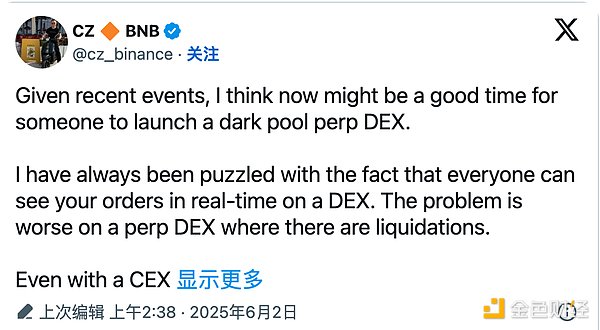

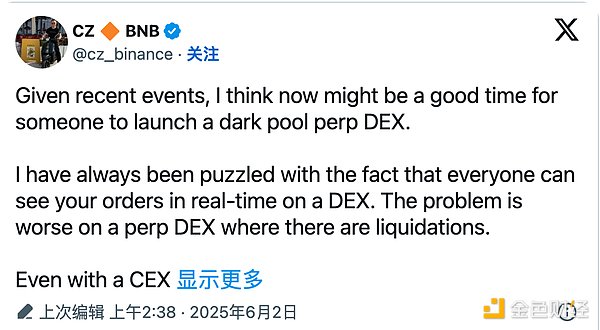

The incident prompted Binance founder CZ to propose a solution on June 1: launching a "dark pool perpetual contract DEX".

His logic is simple: if traders can't see each other's positions, they can't conduct liquidation hunting. Using zero-knowledge proofs to hide order books can protect large investors from being targeted while maintaining decentralization.

Let's take a quick look at the origins of dark pools, their advantages and disadvantages, and the related projects that are currently available in the crypto industry.

Origins of Dark Pools

Dark pools are not new, and despite their mysterious name, they are not illegal in themselves.

Dark pools first appeared in traditional finance in the 1980s, and the core problem they solved was: How to trade large blocks of stock without affecting market prices?

For example, a pension fund needs to sell 10 million shares of Apple. If it sells directly on the open market, the price will collapse quickly; others will also flee first when they see the large order, and as a result, you not only fail to sell all the shares, but also lose more.

The U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) officially approved the Alternative Trading System (ATS) in 1979, allowing institutions to trade anonymously through "dark pools" until the transaction is completed and not announced to the public. In the spring of 2017, dark pools accounted for 40% of the trading volume in the U.S. stock market, far higher than 16% in 2010.

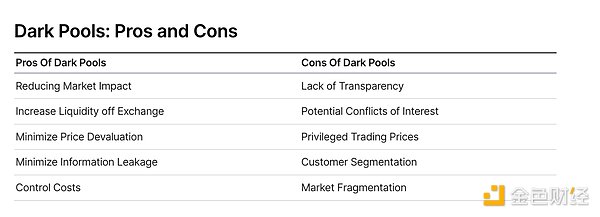

The basic mechanisms of dark pools include:

Hidden order book, private matching of orders

Transactions are completed at negotiated or middle prices

Announced only after transactions are completed

Usually only open to institutions

Why the crypto world needs dark pools more

If dark pools are important in traditional finance, they may be a necessity in the blockchain world.

In DeFi, extreme transparency becomes a flaw - every transaction, every position, and every address is completely public.

In traditional finance, at least your transactions will not be seen by the whole world in real time; in DeFi, your wallet is your own "bulletin board". This has led to the frequent occurrence of the following "predatory" behaviors:

MEV (Maximum Extractable Value): Robots monitor transactions in the memory pool and conduct front-running arbitrage. It's like someone peeked at your cards and placed a bet.

Copy trading: Profits can be made by simply copying the wallet operations of successful traders, which weakens the advantages of strategy developers.

Liquidation hunting: The Wynn case is a classic example. Public leveraged positions are easy to calculate and attack.

Quote decay: When market makers detect that large orders are about to be traded, they withdraw liquidity and increase slippage.

Dark pools use the following privacy technologies to address the above problems:

ZKPs (zero-knowledge proofs): Verify the validity of transactions without disclosing details.

MPC (Multi-Party Computation): No party can see all the information during the order matching process.

TEE (Trusted Execution Environment): Execute transactions in a hardware-isolated secure environment. For example, Uniswap’s new L2 chain “Unichain” uses TEEs to hide transaction information and avoid MEV extraction.

This type of technology makes transactions both private and verifiable, anonymous and auditable — while retaining the “trustless” nature of blockchain, it protects the privacy of traders.

Current dark pool projects

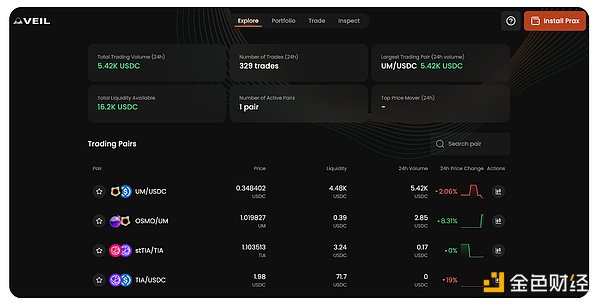

The following projects have implemented or are developing dark pool related functions:

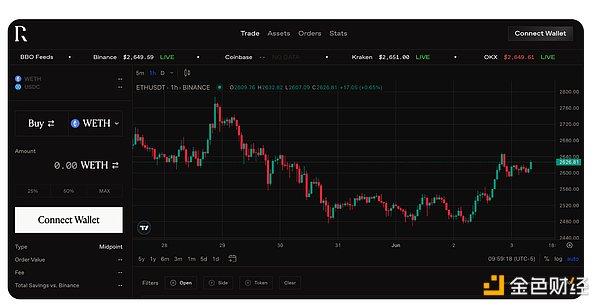

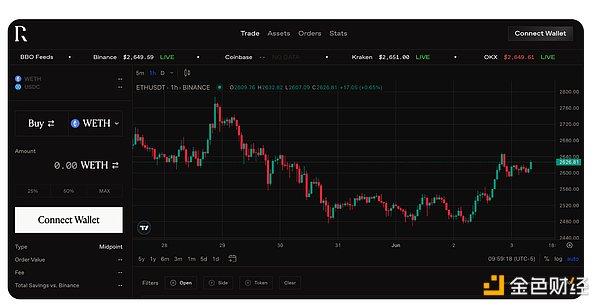

Renegade is an on-chain dark pool based on multi-party computation (MPC) on the Arbitrum platform, which ensures privacy and no slippage in transactions. The platform matches transactions of its supported tokens directly between peers at Binance's mid-price, eliminating front-running and price manipulation. This means that large transactions can be conducted privately without any impact on market prices.

Silhouette is different. It adds privacy to transactions by hiding transaction matching, building on the deep liquidity and fast transactions of the Hyperliquid exchange. Although the platform is still in development and there is no specific launch timeline, it does not require the use of any special wallets, making it easy to get started while enjoying enhanced privacy.

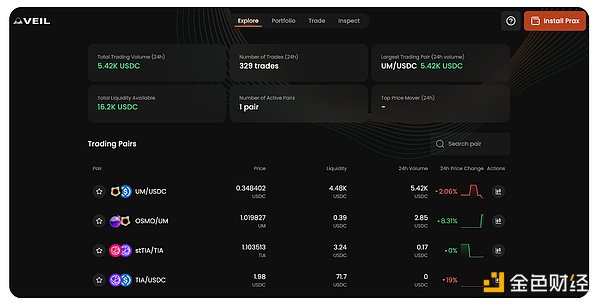

Penumbra provides dark pool spot market capabilities by creating a new, privacy-centric blockchain in the Cosmos ecosystem. It uses zero-knowledge proofs (ZKP) to hide all transactions, balances, staking, and even governance. Its decentralized exchange (DEX) protects transactions through batch auctions to prevent front-running and uses cryptography to ensure complete privacy.

sFOX is a US-based company dedicated to helping large investors (mainly institutional investors) acquire and trade cryptocurrencies, and provides dark pool services regulated by the Financial Crimes Enforcement Agency (FinCEN) and the State of Wyoming. Through its services, sFOX allows institutional investors to use hidden orders and combine liquidity from more than 30 exchanges to carefully execute large trades.

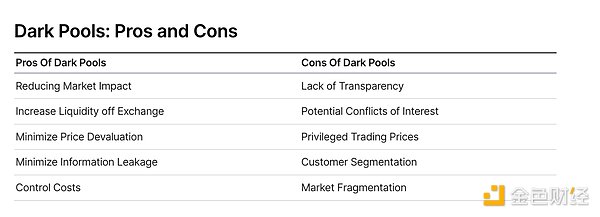

Why aren't dark pools widespread yet?

Despite the many advantages of dark pools—such as protection against maximum extractable value (MEV), liquidation hunting, and front-running—they are not yet widespread because there are significant technical and practical challenges in building dark pools, especially for perpetual futures markets.

The fundamental challenge is how to achieve both privacy and verifiability. You need to prove that a trade is fair without revealing the content of the trade. While the aforementioned technologies, such as zero-knowledge proofs (ZKPs), multi-party computations (MPCs), and trusted execution environments (TEEs), provide a viable path, it is extremely complex to apply these technologies well—it is not enough to just hide the data, but also to ensure that the information cannot be inferred by other means. In other words, if the price of a so-called "private AMM" can be queried at any time, it is actually no longer private.

Dark pools also face a classic “chicken or egg” problem: they need enough volume to work well, but if there is no ready liquidity, traders will not use it. This is particularly acute in perpetual contract markets, which require a continuous supply of funds and an active liquidation mechanism, relying on highly active liquidity.

Then there is the trust paradox. The lack of transparency is the value of dark pools, but it can also lead to skepticism. How do we know the price is fair when we can't see the transaction? This problem is even more prominent in the cryptocurrency industry, where "trust but verify" is a core credo. Dark pools could theoretically become a tool for market manipulation rather than a preventive mechanism. For example, by removing a large amount of trading volume from the open market, dark pools could distort the price discovery process and form a two-track market structure: institutional investors get better prices in private markets, while retail investors can only trade in the thinner and more volatile open market.

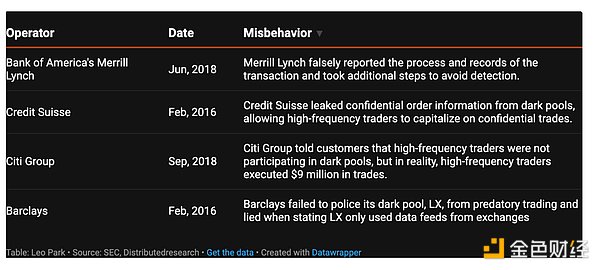

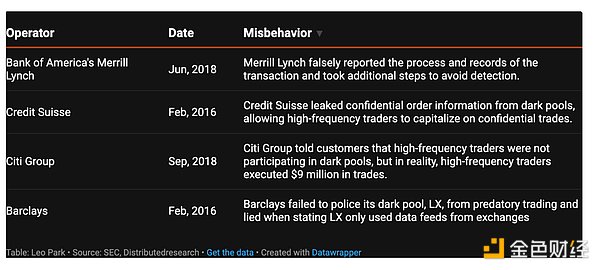

Similar warning examples have been seen in traditional financial markets. For example, Barclays was fined $70 million for lying about its dark pool operations, and other institutions such as Credit Suisse have been punished for giving some traders an unfair advantage.

Finally, launching an on-chain dark pool, especially one for perpetual contracts, faces complex regulatory hurdles. The intersection of derivatives, privacy technology, and cross-border transactions has formed a regulatory maze that few projects have successfully navigated.

Overall, whether or not James Wynn's incident is really a "hunting behavior," it reveals a fundamental tension in the crypto industry: we have built a highly transparent mechanism to achieve a "trustless" system, but this transparency itself may also become a means of attack.

Dark pools provide a solution, but this road is not easy. The challenge is how to give transactions the privacy required to make certain behaviors truly fair while maintaining the "verifiable and fair" nature of cryptocurrency. Projects like Renegade have proven in spot markets that this is possible - using cryptography to prove the fairness of transactions without revealing the details. However, CZ's vision of a "perpetual contract dark pool DEX" has not yet been realized, and only Silhouette is currently working in this direction.

As the crypto industry matures and institutional capital continues to pour into the on-chain world, infrastructure must continue to evolve to protect the big players without sacrificing the interests of the small players. These technical challenges are real, but not insurmountable. Dark pools are not perfect, but they are becoming increasingly necessary.

Weiliang

Weiliang