Buffett buys Bitcoin

Recent reports suggest that Berkshire Hathaway and some of its investment managers may be becoming more lenient toward cryptocurrencies.

JinseFinance

JinseFinance

Author: Buffett; Compiler: Tencent Finance; Source: Xinbang+

To Berkshire Hathaway shareholders:

In 2024, Berkshire's performance exceeded my expectations, even though 53% of the 189 operating companies in which we hold shares reported a decline in earnings. We benefited from a significant increase in predictable investment income due to higher Treasury yields and our significant increase in holdings of these highly liquid short-term securities.

Our insurance business also achieved significant growth in earnings, with GEICO (the fourth largest auto insurance company in the United States) performing particularly well. Over the past five years, Todd Combs has significantly transformed GEICO, improving efficiency and updating underwriting standards. GEICO is a gem worth holding for the long term, but it needs to be refinished, and Todd is working tirelessly to do that. Although the reform is not yet complete, progress in 2024 was impressive.

Overall, property and casualty (P/C) pricing strengthened in 2024, reflecting a significant increase in losses from convective storms. Climate change may have already arrived quietly. However, no "catastrophic" event occurred in 2024. But one day, any day, a truly shocking insurance loss may occur - and there is no guarantee that it will only happen once a year.

The P/C business is so important to Berkshire that I will discuss it further in the second half of the open letter.

Total earnings improved in Berkshire's railroad and utility businesses, our two largest businesses outside of insurance. Yet both businesses still have plenty of room for improvement. We increased our ownership of the Utilities business from about 92% to 100% at the end of 2024 at a cost of about $3.9 billion, $2.9 billion of which was paid in cash and the balance in Berkshire Class “B” stock.

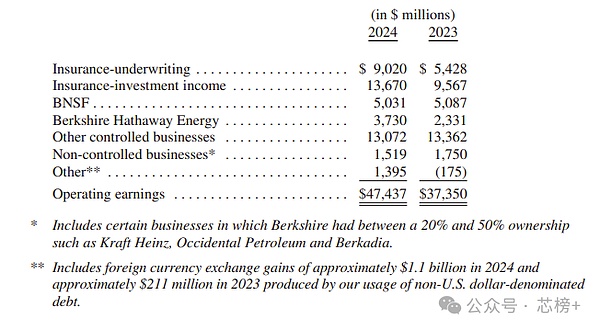

All told, we recorded operating earnings of $47.4 billion in 2024. We often — and even tirelessly — emphasize this metric over earnings reported in K-68 under GAAP.

Our calculations exclude capital gains and losses, realized or unrealized, on the stocks and bonds we hold. Over the long term, we believe earnings are likely to prevail, or else why would we buy these securities? Even though the annual numbers can fluctuate wildly and unpredictably. Our time horizons for these investments often extend far beyond a single year, and in many cases span decades. These long-term investments can sometimes make cash registers ring like church bells.

Here is a breakdown of earnings for 2023-2024, with all calculations net of depreciation, amortization, and income taxes. EBITDA is Wall Street’s favorite metric, but it’s not for us. (Unit: Millions of U.S. Dollars)

Notes: 1) Includes certain businesses in which Berkshire owns 20% to 50% of its shares, such as Kraft Heinz, Acor Petroleum, and Beccadia. 2) Includes foreign currency exchange gains of approximately $1.1 billion in 2024 and approximately $211 million in 2023, which come from our use of non-U.S. dollar-denominated debt.

Sixty years ago, the current management took over Berkshire. That decision was a mistake—my mistake—and it haunted us for 20 years. Charlie immediately spotted my obvious error: Although the price I paid for Berkshire looked cheap at the time, its business—a large northern textile business—was dying.

The U.S. Treasury had already quietly foreseen Berkshire’s fate. In 1965, the company paid no income taxes, an embarrassing tenure that lasted a decade. Such behavior might be understandable for some hot startup, but for a pillar of American industry, it was undoubtedly a warning sign that Berkshire was destined for decline.

Imagine the Treasury’s surprise 60 years later: the company, which still operates as Berkshire Hathaway, paid far more in corporate income taxes than the U.S. government received from any company, even the trillion-dollar American tech giants.

To be precise, Berkshire paid four payments totaling $26.8 billion to the IRS in 2024. That figure represents about 5% of all taxes paid by all U.S. corporations. (In addition, we pay significant income taxes to foreign governments and 44 states.)

It is worth noting that this record tax payment was made possible by one key factor: Berkshire shareholders received only one cash dividend between 1965 and 2024. On January 3, 1967, we paid that one and only dividend—$101,755, or 10 cents per Class A share. (I can no longer remember why this decision was presented to Berkshire’s board of directors at the time; in retrospect, it feels like a nightmare.)

For 60 years, Berkshire’s shareholders have supported a consistent reinvestment strategy that has enabled the company to accumulate taxable income. Cash income tax payments to the U.S. Treasury, which were meager in their first decade, now total more than $101 billion…and counting.

That’s a number too large for the average person to comprehend. Let me rephrase the $26.8 billion in taxes we paid last year.

If Berkshire sent a $1 million check to the Treasury every 20 minutes throughout 2024—imagine 366 days and nights, since 2024 is a leap year—we’d still owe the federal government a substantial tax bill at the end of the year. In fact, the Treasury may not tell us until mid-January, when we can take a break, get some sleep, and prepare for our 2025 tax payments.

Berkshire’s holdings are held in two ways. On the one hand, we own controlling interests in many businesses, holding at least 80% of the shares. But generally, we own 100% of the shares.

These 189 subsidiaries resemble common stocks in the market, but they are not identical. The total value of these businesses is in the hundreds of billions of dollars, including some rare gems, many well-run but not great businesses, and some disappointing laggards. We do not own any major laggards, but there are some businesses that I should not have bought.

On the other hand, we own minority stakes in more than a dozen very large and profitable businesses that are household names, such as Apple, American Express, Coca-Cola, and Moody's. These companies earn very high returns on the net tangible equity required to operate. As of the end of 2024, the marketable value of our holdings is $272 billion. Understandably, truly great businesses are rarely sold as a whole, but small portions of these businesses can be bought on Wall Street during trading on Monday through Friday, and occasionally sold at bargain prices.

We choose equity vehicles impartially and always based on where your (and my family’s) savings can best be deployed. Often, we don’t have any attractive investments. But on rare occasions, we find ourselves in the middle of an opportunity. Greg demonstrates the same ability as Charlie in these moments.

With tradable stocks, it’s easy to change strategy when I’m wrong. But it’s important to emphasize that Berkshire’s current size impairs the ability to make these choices. We can’t buy or sell stocks easily. Sometimes it takes a year or more to build or divest an investment. In addition, with minority companies, we can’t replace management when necessary or control where the money goes. Even if we’re unhappy with the decisions, we can’t intervene effectively.

With holding companies, we can lead these decisions, but we have much less flexibility to deal with mistakes. In fact, Berkshire almost never sells a holding unless we face a problem we believe we can’t solve. The upside is that some business owners have sought Berkshire’s help. Sometimes, this is a distinct advantage for us.

Although some analysts currently believe that Berkshire’s cash position is too large, the majority of your money is still invested in stocks. This preference will not change. While the value of our marketable stock holdings has declined from $354 billion to $272 billion in 2024, the value of our non-listed controlling stakes has increased and remains far higher than the value of the marketable stock portfolio.

Berkshire shareholders can rest assured that we will always keep the vast majority of their money invested in stocks, primarily U.S. stocks, even though many of these businesses have significant international operations. Berkshire will never give preference to holding cash equivalents, preferring to own good businesses, either controlling or partially owned.

The value of paper money can quickly disappear in the event of a fiscal policy error. In some countries, such irresponsible behavior has become customary, and the United States has faced this risk in its short history. Fixed-interest bonds offer no protection against currency debasement.

However, as long as a company or individual's goods or services are popular with a country's citizens, they can usually find ways to cope with currency instability. The same is true of personal skills. Lacking athletic talent, a beautiful voice, medical or legal skills, or any special talents, I have had to rely on investing in stocks all my life. In fact, I have always relied on the success of American businesses, and I will continue to do so.

In any case, citizens' rational (and preferably imaginative) use of savings is necessary to drive a society's output to continue to grow. This system is called capitalism. It has its flaws, some of which are serious, but it can also work wonders that no other economic system can match. The United States is the best example. Our country has made progress in its short 235 years of history that even the most optimistic colonists could not have imagined when the Constitution was enacted in 1789.

Admittedly, in our early days, we occasionally borrowed foreign funds to supplement our savings. But at the same time, we need many Americans to continue saving, and we need those savers or other Americans to use that money wisely. If the United States consumed all of its output, the country would be standing still.

American progress has not always been beautiful, and our country has always had many villains and promoters who seek to take advantage of those who mistakenly entrust their savings to them. But even with such lawlessness - which still exists today - and many capital investments that ultimately fail due to fierce competition or disruptive innovation, American savings have achieved a quantity and quality of output that no colonizer could have imagined.

The United States began with a population of only 4 million, and despite a brutal civil war in its early years and Americans killing each other, the United States changed the world in the blink of an eye.

In part, Berkshire shareholders have participated in the American miracle by forgoing dividends and choosing to reinvest their income rather than consume it. At first, this reinvestment was negligible and almost meaningless, but over time it grew rapidly, the result of a culture of continuous savings combined with the magic of long-term compounding.

Berkshire’s investment activities now affect every corner of our country, and they continue to do so. Businesses die for many reasons, but unlike human fate, aging is not inherently fatal. Berkshire is more vibrant today than it was in 1965.

Yet, as Charlie and I have always acknowledged, Berkshire could not have achieved its current success anywhere else in the world except in the United States. And the United States would have achieved the same success even if Berkshire had never existed.

So thank you, Uncle Sam. Someday, Berkshire’s descendants will hope to pay you more in taxes than you did in 2024. Please use them wisely and take good care of those less fortunate in life who deserve better. At the same time, never forget that we need you to maintain a stable currency, which requires your wisdom and constant vigilance.

Property-casualty (P/C) insurance remains Berkshire’s core business, and the industry follows a financial model that is rare among large corporations.

Typically, companies incur costs such as labor, materials, inventory, plant, and equipment before or as they sell their products or services. As a result, their CEOs have a good idea of their costs before they sell their products. If the sales price is below costs, managers quickly discover a problem. After all, a cash drain is hard to ignore.

In writing P/C insurance, we receive payments in advance and learn much later what our products cost—sometimes this “moment of truth” is delayed by 30 years or more. (We are still paying huge claims for asbestos exposure that occurred more than 50 years ago.) This operating model has the desirable effect of receiving cash before the insurer incurs most of its expenses, but it also carries the risk that the company may incur losses, sometimes large losses, before the CEO and directors realize it.

Certain insurance categories minimize this mismatch, such as crop insurance or hail damage, where losses are quickly reported, assessed and paid. Other categories, however, can cause executives and shareholders to let their guard down and not even notice that a company is going bust. Think of malpractice insurance or product liability. In “long-term liability” lines, P/C insurers may report to regulators huge, fake profits that have existed for years (or even decades). This accounting treatment is particularly dangerous if the CEO is an optimist or a liar. These possibilities are not fanciful: history has seen plenty of them.

In recent decades, this “collect first, pay later” model has enabled Berkshire to invest large sums of money (“float”) while generally realizing what we consider to be small underwriting profits. We make estimates for “surprises,” and so far, those estimates have been adequate.

We are not discouraged by the large losses we have incurred. (Disasters such as wildfires come to mind as I write this.) Our job is to price these surprises and to calmly take the losses when they occur. Our job also includes fighting “out-of-control” judgments, sham lawsuits and outright fraud.

Under the leadership of Ajit, our insurance business has grown from a little-known Omaha company to a world leader, known for its ability to handle risk and its deep pockets. Moreover, myself, Greg and the members of our board of directors have invested far more in Berkshire than any compensation we have ever received. We do not use options or other unilateral forms of compensation; if you lose money, we lose money. This practice encourages prudence but does not ensure forward-looking behavior.

The growth of P/C insurance depends on the increase of economic risk. After all, without risk, there is no demand for insurance.

Recall that 135 years ago, there were no cars, trucks or airplanes. And now, with 300 million cars in the United States alone, this massive fleet is causing enormous losses every day. Property damage from hurricanes, tornadoes and wildfires is also growing and becoming increasingly unpredictable in its pattern and ultimate cost.

It would be foolish—even crazy—to write 10-year policies for these, but we believe that the risk underwriting for one year is generally manageable. If we change our minds, we will modify the contracts we offer. In my lifetime, auto insurers have generally abandoned one-year policies in favor of six-month policies. This change reduces float but also allows for more flexible underwriting.

No private insurer is willing to take on the amount of risk that Berkshire can offer. Sometimes this advantage can be critical. But we also need to shrink when the price is not right. We must not write policies that are not priced right just to stay in the game. That approach would be tantamount to corporate suicide.

Properly pricing P/C insurance is both an art and a science and is definitely not a business for optimists. Berkshire executive Mike Goldberg—who recruited Ajit—once said, “We want our underwriters to be nervous but not paralyzed when they come to work every day.”

Overall, we like the P/C insurance business. Berkshire can handle extreme losses financially and psychologically without hesitation. Nor are we dependent on reinsurers, which gives us a substantial and lasting cost advantage. Finally, we have excellent managers (no optimists) and are particularly adept at using the huge pool of capital available for investment from P/C insurance.

Over the past 20 years, our insurance business has earned $32 billion in after-tax profits from underwriting, or about 3.3 cents on each dollar of sales. Over the same period, our float has grown from $46 billion to $171 billion. Float may grow slightly over time and, with judicious underwriting (and some luck), could potentially be realized at zero cost.

In addition to our focus on U.S. businesses, our investments in Japan are growing.

It has been nearly six years since Berkshire began buying shares in five Japanese companies that are successfully operating in a manner similar to Berkshire’s own. The five companies, in alphabetical order, are: Itochu, Marubeni, Mitsubishi, Mitsui and Sumitomo. Each has a wide range of operations, many in Japan but others operating around the world.

Berkshire first bought shares in all five companies in July 2019. We simply looked at their financial records and were surprised at how low their stock prices were. Over time, our appreciation for these companies has grown. Greg has met with them several times, and I follow their progress regularly. We both like their capital operations, management, and attitude toward investors.

These five companies increase dividends when appropriate, repurchase shares when appropriate, and their top management compensation plans are far less aggressive than those of their U.S. counterparts.

Our holdings in these five companies are long-term, and we are committed to supporting their boards of directors. From the beginning, we agreed to keep Berkshire's holdings below 10% of each company's shares. But as we approached that limit, the five companies agreed to relax the restrictions modestly. As time goes by, you may see Berkshire's holdings in these five companies increase. As of the end of 2024, Berkshire's total investment cost is $13.8 billion, and the holdings are worth a total of $23.5 billion.

At the same time, Berkshire has been increasing its yen-denominated borrowings. All borrowings are fixed-rate, with no "floating rates." Greg and I do not have any expectations about future foreign exchange rates, so we seek a position that is approximately currency neutral. However, under GAAP rules, we must periodically recognize in earnings any gains or losses on the yen we borrow, and through the end of 2024, we have included $2.3 billion of after-tax gains, $850 million of which occurred in 2024, due to the strength of the U.S. dollar.

I expect Greg and his successors to hold this Japanese portfolio for decades to come, and that Berkshire will find other ways to engage more productively with these five companies in the future.

We also like the mathematical logic of the current yen-balanced strategy. As I write this, we expect annual dividend income from our Japanese investments to total approximately $812 million in 2025, while interest costs on our yen-denominated debt will be approximately $135 million.

I hope you will join us in Omaha on May 3. This year our schedule has been tweaked, but the basics remain the same. Our goal is to answer your many questions, support you in making connections with friends, and have you leave with a good impression of Omaha. The city is waiting for you.

We will continue to have the same team of volunteers to provide you with a variety of Berkshire products that will both lighten your wallet and brighten your day. As in previous years, we will be open on Friday from 12 noon to 5 pm and offer lovely Squishmallows, Fruit of the Loom underwear, Brooks running shoes, and many other tempting items.

This year we will only sell one book. Last year we launched Poor Charlie’s Almanack and it sold out quickly—all 5,000 copies were sold by the close of business on Saturday. This year we will launch Berkshire Hathaway 60 Years. In 2015, I asked Carrie Sova, a former assistant to Buffett who was managing the annual meeting activities and many other tasks, to try to write a lighthearted and entertaining history of Berkshire. I gave her full freedom to use her imagination, and she soon wrote a book that amazed me with its creativity, content and design.

Sova later left Berkshire to start a family and now has three children. But every summer, the Berkshire office team gets together to watch the Omaha Storm Chasers play a baseball game against a Triple A opponent. I invited some old employees to join us, and Sova usually brought her family. At this year's event, I boldly asked her if she would be willing to write a 60th anniversary edition of Berkshire featuring Charlie's photos, quotes and little-known stories.

Despite having three young children to care for, Sova immediately agreed. As a result, we will sell 5,000 copies of the new book from 7 a.m. to 4 p.m. on Friday afternoon and Saturday during the shareholder meeting.

Sova refused to be paid for her efforts in writing the new book. I suggested that she join me in signing 20 copies of the new book and give them to any shareholder who donated $5,000 to the Stephen Center in South Omaha, which provides services to homeless adults and children. The Kizer family (beginning with my old friend Bill Kizer Sr., who, like Sova’s grandfather, has helped the organization for decades) will make a matching donation to whatever funds are raised through the sale of these 20 signed copies.

Becky Quick will cover our slightly modified gathering on Saturday. Quick knows Berkshire inside and out and always schedules interesting interviews with executives, investors, shareholders and celebrities. She and the CNBC team do an excellent job of broadcasting our meetings around the world and of archiving a wealth of Berkshire-related material. The idea for the archive goes to our director, Steve Burke.

This year we will not have a film screening, but will begin a little earlier, at 8 a.m. I will give a brief opening speech, and then we will move quickly into a question-and-answer session, alternating between Quick and the audience.

Greg and Ajit will join me to answer questions, and we will take a half-hour break at 10:30 a.m. Only Greg will remain on the stage with me when we resume at 11 a.m. This year we will close at 2 p.m., but shopping in the exhibit area will be open until 4 p.m. You can find full details of the weekend's activities on page 16. Pay special attention to the Brooks Run, which is always popular on Sunday morning. (I'll be sleeping in.) My clever and pretty sister, Bertie, whom I wrote about last year, will be in attendance, along with her two equally pretty daughters. Observers agree that the genes for such dazzling results come only from the female side of the family. (Weeping) Bertie is now 91, and we talk every Sunday on the old-fashioned telephone. We talk about the joys of old age and discuss such exciting topics as the merits of a cane. In my case, the usefulness of a cane is limited to keeping me from falling flat on my face. But Bertie often hammers me home with the added bonus she enjoys: Men no longer “hit up” on a woman when she uses a cane, she tells me. Bertie’s explanation is that male egos make a little old lady on crutches simply an inappropriate target. At this point, I have no data to refute her claim.

But I have my suspicions. I can’t see much from the stage at meetings, and I’d appreciate it if attendees would keep an eye out for Bertie. Let me know if the cane really does the trick. I bet she’ll be surrounded by men. For people of a certain age, the scene will bring to mind Scarlett O’Hara in Gone with the Wind and her legion of male admirers.

The Berkshire directors and I welcome you to Omaha, and I hope you’ll have a great time and perhaps make some new friends.

Recent reports suggest that Berkshire Hathaway and some of its investment managers may be becoming more lenient toward cryptocurrencies.

JinseFinance

JinseFinanceWarren Buffett’s decision to end his charity lunch auction is linked to the controversies involving Sun Yuchen, which exposed significant flaws in the event’s integrity and effectiveness.

Edmund

EdmundIt’s just that most people want to get rich overnight, and are not willing to get rich slowly.

JinseFinance

JinseFinanceAs more and more Wall Streeters flock to Bitcoin. The critics are getting older. There are fewer and fewer people.

JinseFinance

JinseFinanceAfter a week of silence, in the early morning of February 27, the price of Bitcoin suddenly changed again, exceeding US$54,000, and then soared, once exceeding US$57,000 at around 10 a.m. on the 27th.

JinseFinance

JinseFinanceDespite Bitcoin (BTC) climbing over 80% since the turn of the year, the flagship digital asset is not without its detractors.

Finbold

Finbold Coinlive

Coinlive It appears that the rising popularity of Bitcoin and other cryptocurrencies — despite the continuous carnage on the broader crypto ...

Bitcoinist

BitcoinistThe “Oracle of Omaha” now has more direct/indirect investments in Bitcoin and similar cryptocurrencies in his portfolio.

Cointelegraph

Cointelegraph“If you told me you own all of the Bitcoin in the world and you offered it to me for $25 I wouldn’t take it because what would I do with it?” Warren Buffett said.

Cointelegraph

Cointelegraph