Crypto exchange tokens are an important source of financing for centralized crypto exchanges, and they are at the heart of some of the most turbulent events in the crypto industry. This article constructs a tractable model for analyzing the exchange rate of crypto exchange tokens that combines user demand, investment demand, and token buyback commitments that are common on exchanges. This article derives closed-form solutions for the valuation of exchange tokens and the time required to fulfill buyback commitments. Buyback commitments can increase the amount of funds raised through token sales, but the increase is always less than the discounted cost of the buyback commitment.

I. Introduction

The introduction details the importance of cryptocurrency exchanges and their tokens in the modern financial system. The article points out that despite the challenges faced by crypto exchanges, such as regulatory uncertainty and market volatility, they have successfully raised large amounts of capital by issuing tokens. The introduction also mentions several notable cases, such as Binance raising funds by issuing BNB tokens and using these funds to expand its business and improve its technical infrastructure. In addition, the introduction also discusses the impact of crypto exchange tokens on market liquidity and how they appear in the mainstream market as investment tools.

The contents of these two parts lay a solid theoretical foundation for the entire article, not only outlining the core issues and methods of the research, but also highlighting the important role and potential impact of crypto exchange tokens in the global financial market. Through the detailed background introduction and model preview, readers can have a clear understanding of the research direction and purpose of the article. The following chapters will further develop specific model analysis and case studies to provide in-depth insights into the economic mechanism of crypto exchange tokens.

II. Related Literature

The literature section reviews the academic literature on cryptocurrency exchange exchange rates and theoretical models for using cryptocurrencies or tokens to raise funds for companies or platforms.

Main research and progress:

1. Understanding of cryptocurrency trading rates:

Academia has used a variety of theoretical models to explain changes in cryptocurrency trading rates. These studies generally explore how market supply and demand, investor behavior, and macroeconomic factors affect cryptocurrency prices and trading activities.

2. Fundraising potential:

A large number of theoretical studies focus on the potential of using cryptocurrencies or tokens to raise funds. These studies discuss how crypto assets can help companies or platforms raise funds quickly, and how these funds can be used for technological innovation and business expansion.

3. Token economics:

Some of the latest papers focus on "tokenomics", exploring the characteristics of tokens and how these characteristics are closely related to other aspects of the cryptocurrency exchange model. These studies typically include token buyback strategies, price incentives, and how tokens influence user and investor demand.

While existing studies have provided valuable insights, there are still some gaps in the current literature. In particular, the valuation of exchanges committing resources to repurchase a certain number of tokens has not been fully explored. In addition, the possible impact of strategic investors taking advantage of exchanges' commitments has not been adequately studied. This paper seeks to fill these gaps by building a model to analyze the valuation of exchange tokens and examine how strategic investors influence the market.

Background

A considerable number of the world's largest centralized cryptocurrency exchanges have issued their own tokens to raise funds or enhance customer loyalty. Table 1 summarizes the key characteristics of crypto exchange tokens sorted by market capitalization. The list includes tokens issued by six of the top ten centralized crypto exchanges by trading volume. The market capitalization of these tokens is dominated by Binance’s BNB token, which is also the token with the longest trading history (starting in September 2017). All exchanges in the table offer trading fee discounts to their token holders, although the requirements for traders to qualify for discounts vary from exchange to exchange. The most common scheme is to offer discounts to traders who pay fees with tokens. Another popular scheme is to require traders to hold a certain amount of tokens to qualify for discounts. Finally, some exchanges offer discounts based on the number of tokens held by traders. This latter approach is sometimes used to provide additional discounts on top of traders paying fees with exchange tokens. Some exchanges also aim to increase the attractiveness of their tokens by offering alternative benefits that may attract specific user groups, such as raffles or early access to new token launches.

Almost all exchanges have committed to buyback and burn tokens in some specific way. In all of these cases, the resources committed are proportional to the activity of the trading platform or its financial success. Platforms use various measures to calculate the amount of resources committed to buyback, ranging from a portion of trading fees (e.g., FTX and OKX) to a portion of profits (e.g., Binance and Kucoin). In addition, most exchanges report clear targets for the total share of tokens they intend to buyback and burn. This percentage ranges from one-tenth of some smaller tokens to 100% of the above-mentioned LEO tokens.

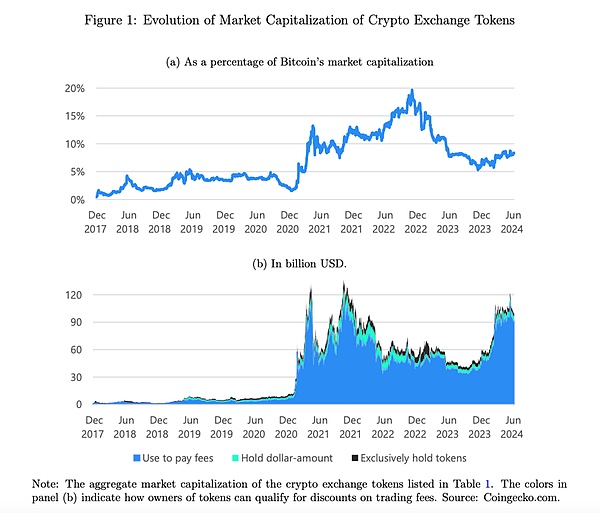

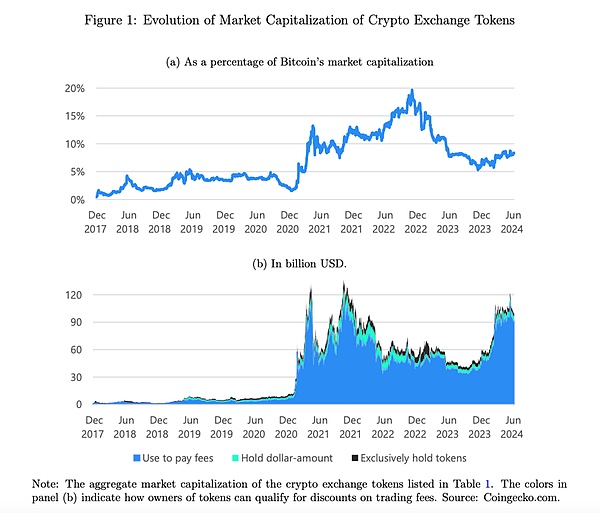

Figure 1 shows the evolution of the market capitalization of crypto exchange tokens. Between 2019 and 2020, the market capitalization of crypto exchange tokens remained stable at approximately 5% as a percentage of Bitcoin's market capitalization. At the beginning of 2021, the market capitalization exploded from a level of about $5 billion to a level of more than $100 billion. This growth was almost entirely due to the strong appreciation of existing crypto exchange tokens during the surge in the Bitcoin exchange rate. During this period, the market share of crypto exchange tokens calculated by Bitcoin market capitalization roughly doubled to about 10%. After imitating the double peak of Bitcoin prices in 2021, the market value of crypto exchange tokens has fallen as the Bitcoin exchange rate has fallen. Since the second half of 2023, the value of crypto exchange tokens has also increased as the Bitcoin exchange rate has risen. In the chart, the value of crypto exchange tokens reached a final level of about $100 billion.

Fourth, Model Brief

This model covers two main characteristics of cryptocurrency exchange tokens. First, token holders will receive certain benefits from the issuer; second, exchanges usually promise to use part of their resources to repurchase and destroy part of the tokens at market prices, thereby withdrawing these tokens from circulation.

Model setting:

Time continuity: The model assumes that time is continuous.

Token issuance: The exchange issues tokens at the initial time \( t = 0 \) with a quantity of \( M > 0 \).

Market price: The market price or exchange rate of the token at any time\( t \) is represented by \( S(t) \).

Token repurchase and destruction: The exchange promises to repurchase at least \( U \geq 0 \) tokens at the market price over time and destroy them permanently, and the amount of funds used is represented by \( Y$(t) \).

Model operation:

Token liquidity: If the exchange operates normally, the number of tokens it will repurchase and destroy between any time \( t1 \) and \( t2 \) is represented by \( W(t1, t2) \).

Total repurchase amount: As of time \( t \), the total number of tokens that the exchange has repurchased and destroyed is represented by \( W(0, t) \).

Time point for completion of repurchase: The time when the exchange completes the repurchase plan is represented by \( T \). Token Demand: Utility Demand: The benefits provided by the issuer result in a time-varying demand for the utility of the token, expressed as \( X$(t) \), where \( X \) is in USD. Threshold Demand: Some exchanges require users to hold tokens above a certain USD threshold to receive benefits such as discounts. Payment Discounts: Other exchanges offer discounts conditional on users paying fees with issued tokens. Investor Role: Investor Held: Tokens not held by users for utility purposes are held by investors, who are risk-neutral and assess the present value of their investment.

Non-strategic investors: These investors take the token price as a given and do not consider the impact of their actions on the token price.

Platform activity:

Activity growth: Assume that the activity of the trading platform grows at a fixed growth rate \( g < r \) until the possible collapse of the platform.

Activity volume: In the absence of a collapse, the platform's activity volume at time \( t \) is

\( A(t) = e^{gt} \), otherwise \( A(t) \) is close to 0.

This model considers the utility demand of tokens and how the amount of resources invested by the exchange to repurchase tokens is proportional to the platform activity, further setting the probability of exchange operation and the intensity of default, providing a comprehensive analytical framework for understanding the market dynamics of exchange tokens.

V. Equilibrium Analysis

A. Graphical Representation of Market Clearing Conditions

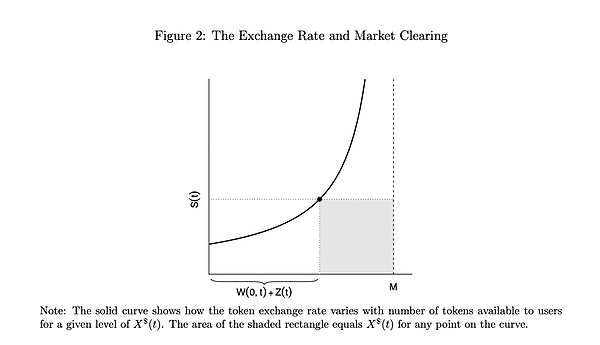

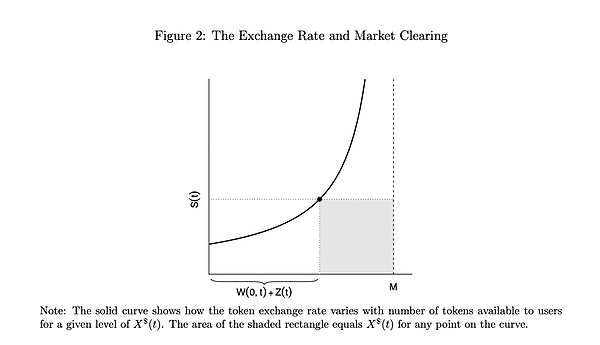

Before analyzing the equilibrium results, the article provides a graphical representation of the market clearing conditions. Figure 2 shows the mechanism of the market clearing conditions, where a given value of X$(t) is represented by the shaded rectangle in the figure. The upward sloping curve represents the supply curve of tokens provided by users to investors and trading platforms. The total amount of tokens held by investors and trading platforms is W(0,t)+Z(t), and users hold the remainder, that is, M−W(0,t)−Z(t). The US dollar balance maintained by users is X$(t). If the exchange rate rises, users are willing to provide more tokens because they need fewer tokens to maintain the same US dollar balance X$(t). This leads to an upward curve in the relationship between the exchange rate and the number of tokens for investment purposes.

B. Equilibrium Exchange Rate with and without Investors

The equilibrium exchange rate level depends on whether the platform's buyback commitment is large enough to attract investors to hold tokens. To keep investors holding tokens, the required buyback resources increase with the increase of investors' expected returns and the increase of the platform's failure rate, and decrease with the increase of the platform's growth rate.

Proposition 1

In an environment with non-strategic investors, investors will hold tokens at the beginning only when Y$ > (r + λ−g)X$. If there is no crash, the equilibrium exchange rate of the token S(t) depends on the execution of the buyback plan. The duration of the buyback T depends on the number of tokens U that the platform promises to buy back and the resources Y$ invested. If investors do not hold tokens, the equilibrium exchange rate still evolves according to user demand.

This proposition confirms the intuitive idea that the duration of the buyback program T increases with the number of repurchased tokens and decreases with the platform's resource commitment. Higher user demand X$ will make the platform buy back tokens at a higher price, thereby extending the time it takes to complete the buyback.

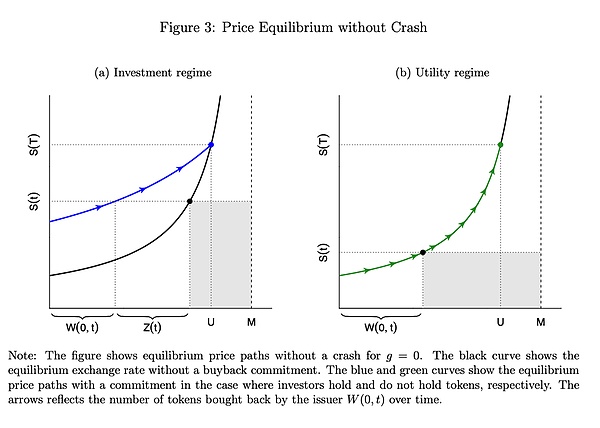

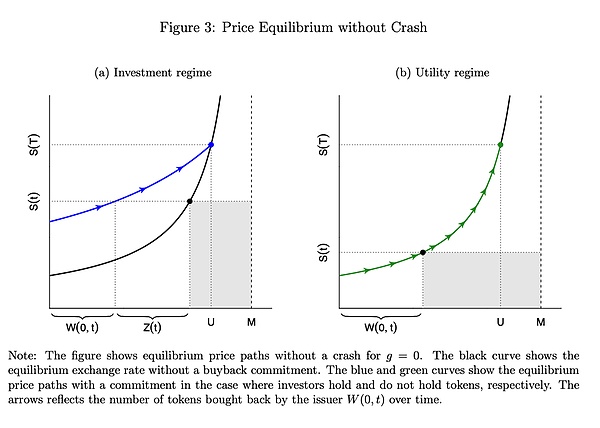

Figure 3: Price equilibrium without collapse

Figure 3 shows the evolution of the exchange rate under two equilibrium scenarios without collapse.

Panel (a) shows the equilibrium path under the buyback program when investors choose to hold tokens; Panel (b) shows the equilibrium path when investors do not hold tokens and the platform only buys back from users. In the case of g=0 (no platform growth), the black curve does not change, and the change in the exchange rate is completely driven by buybacks.

Corollary 1

In a full buyback plan, if Y$ > (r+ λ−g)X$, then the initial equilibrium exchange rate is

S(0) = 1/M * Y$/(r + λ−g). Otherwise, the initial equilibrium exchange rate is S(0) = X$/M. If investors hold tokens, the change in the exchange rate is similar to the valuation of continuously growing cash flows under the Gordon growth model. If investors do not hold tokens, the initial exchange rate only reflects the ratio of user demand to the number of tokens.

VI.Cost of the Platform's Buyback Program

A. The Gap between the Cost of Capital and the Required Rate of Return

This paper uses a model to evaluate the difference between the additional funds raised by an exchange through a buyback commitment and the expected cost of the buyback program. The funds an exchange receives from selling tokens with a buyback commitment are equal to the total number of tokens multiplied by the equilibrium exchange rate. Without the buyback commitment, the exchange's revenue from selling tokens is X$, so the incremental revenue brought by the buyback commitment is the difference. C represents the expected cost of the buyback program over the entire period, which can be obtained by calculating the discounted cost of the entire program.

Proposition 2

By offering a buyback commitment, an exchange can raise less additional funds than its expected discounted cost.

This proposition states that the cost of raising funds through buyback commitments is higher than the rate of return required by investors. Therefore, if exchanges can raise funds at a lower cost through more efficient capital markets, they should avoid buyback commitments.

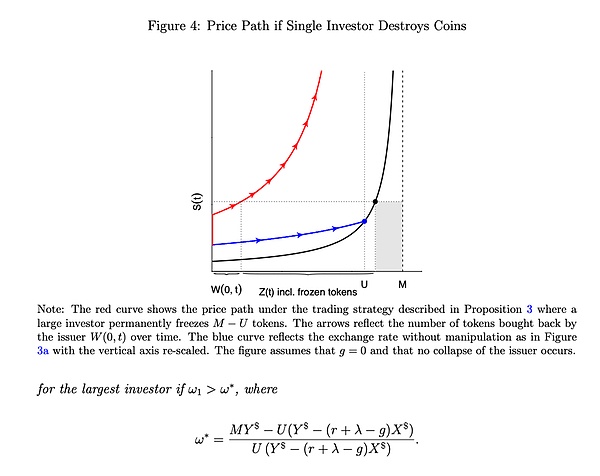

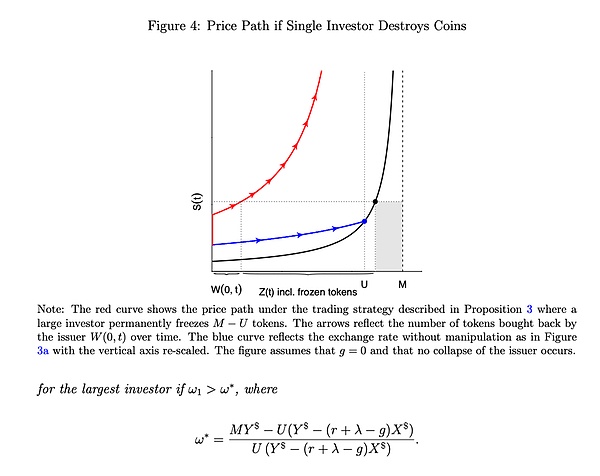

B. Additional costs under price manipulation

Issuing tokens through buyback commitments may result in higher costs, especially the possibility that large investors can manipulate prices by "burning" tokens (i.e., freezing tokens permanently). In this case, the platform may be forced to buy back indefinitely, pushing up the price of tokens.

1. Single large investor

Proposition 3

If a large investor holds all the tokens that are not held by users, the investor can destroy some of the tokens, provided certain conditions are met. This causes the token price to rise and the buyback rate to slow down, ultimately resulting in the platform being unable to complete the buyback plan and the price continuing to rise.

2. One large investor, multiple small investors

Proposition 4

If the proportion of tokens held by the largest investor reaches a certain level, it is beneficial for it to destroy some tokens. In this case, even if other small investors join the destruction action, the largest investor can still profit from it.

3. Many small investors

When no single investor holds enough tokens to manipulate, multiple investors can profit by destroying tokens in a collaborative way. This kind of cooperation is possible through multi-input transactions on the blockchain, although coordinating multiple investors in practice may be more complicated.

4. Preventing Manipulation

Platforms can prevent manipulation by limiting the number of tokens promised for buyback. If the platform promises to buy back more than half of the total token supply, it is vulnerable to manipulation. Therefore, many platforms usually limit the proportion of buyback commitments to less than 50%.

VII. Users with Investment Motivations

In this section, we discuss the situation where user demand for tokens is affected by the rate of its price appreciation, especially when the buyback plan is a full buyback. Even if the platform only commits a small amount of resources for the buyback, as long as users have investment motivations, the buyback commitment will still have an impact on the token price, thereby affecting the amount of funds raised by the platform through token sales.

Proposition 5

When user demand depends on the token appreciation rate, the more resources are pledged in the buyback, the more user demand and the funds raised by the platform through the token sale will be.

For example, if the user's utility function is a logarithmic function, the more resources are pledged in the buyback, the higher the initial equilibrium exchange rate will be.

VIII. Conclusion

This paper concludes that buyback commitments have a significant impact on the price dynamics of crypto exchange tokens and can cause drastic price fluctuations in some cases. Buyback commitments are a costly fundraising method that may be exploited by large investors or multiple small investors. Therefore, the presence of buyback commitments often indicates that the platform faces financing barriers in traditional capital markets.

Weatherly

Weatherly