Author: Kieren James-Lubin, CoinTelegraph; Translator: Baishui, Golden Finance

ETH was conceived in late 2013 and launched in July 2015. I started working on Ethereum in the summer of 2014, and the decade seems unimaginable. As these milestones pass, it’s useful to check what we expected versus what actually happened.

Blockchains and tokens are not unifying, they are proliferating

Blockchains have strong network effects, almost by definition. As a result, one might expect there to be a small number of blockchains, or even a single blockchain, where most end-user activity occurs. Ethereum was created in part to “one chain to rule them all,” in stark contrast to the practice at the time of making a new blockchain for each new feature.

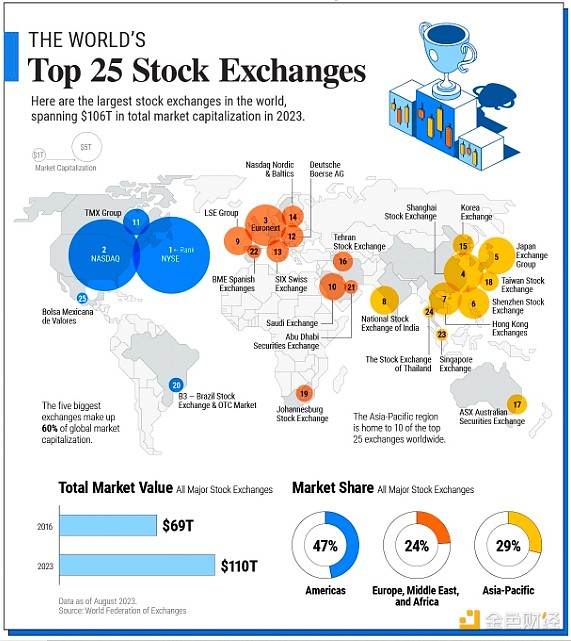

Social networks and stock markets exhibit consolidation behavior — we have a popular social network for roughly every use case (X/Twitter — text, Instagram — pictures, YouTube — videos, etc.). There are two popular stock markets in the United States. Most countries have one or none, and only the top 20 or so stock markets are truly globally significant. By comparison, there are about 2.5 million cryptocurrencies—a fivefold increase from 2021. While many of these tokens and blockchains may not see a lot of use, there are more than 50 billion-dollar tokens and blockchains by September 2024. Blockchains and blockchain-based tokens are relatively easy to build and raise money, so it makes sense that there would be a large number of them. Ethereum has greatly facilitated this activity, reducing the issuance of new tokens to a short snippet of code or even a few clicks. Private investment often chases hot areas, with large amounts of money flowing into a particular category - such as artificial intelligence and blockchain, or ride-sharing companies in the past.

Top 25 stock exchanges in the world. Source: Visual Capitalist

We usually see market consolidation, with one to three winners taking most of the market share, and other players being acquired or shut down. In contrast, blockchains and blockchain-native tokens are strangely resilient, with some projects lasting forever even if they are no longer actively developed. Some projects will make a comeback — Dogecoin, for example, had a long period of dormancy but has seen a resurgence of activity since 2020.

The “markets decide everything” thesis has yet to be proven

Roughly around 2014, every long discussion about the uncensorability of blockchain technology would eventually turn to assassination markets — markets that allow speculators to bet on the time of someone’s death. Assassination markets did first appear in 2018, but don’t seem to have lasted. Prediction markets in areas that were popular before blockchain — elections and sports — have become popular, with huge volumes recently.

Less not so dramatic, decentralized on-chain insurance has long been conceptualized but seems to remain fringe. We can imagine countless micro-insurance markets — will my train arrive on time? If not, will I get compensation? But simply having the ability is not enough for these markets to exist. There is not enough interest in these market operations – at least not yet.

Institutional adoption is progressing differently than expected

Institutional adoption is more about new assets than migrating business processes, and legacy assets are coming to blockchain more slowly than expected.

In the early days of the tech industry, government (especially defense) is often your first customer. Well-funded institutions hire technologists who can take less mature products and get better results than what was available at the time. This may be the adoption path for blockchain technology, especially given the strong interest from traditional financial institutions.

Instead, the use cases that are digitally successful for large institutions tend to be consumer. The technology may be too transformative to be incrementally adopted and for traditional players to use it for core business processes. New asset classes have been a major focus, with brands such as Nike raking in a staggering $185 million in non-fungible token (NFT) revenue and the iShares Bitcoin Trust managing over $20 billion in revenue.

Startups have been more successful than traditional institutions in putting traditional assets on-chain. Tether, with a market cap of $120 billion, is the most obvious success story. Large financial institutions have much larger AUM, with BlackRock leading the way with $9 trillion. But relatively speaking, their on-chain actions so far have been very few.

The evolution of this industry has completely caught me by surprise. It’s been strange, disappointing in some ways, but amazing in others. In his 1997 letter to shareholders—a year when Amazon had revenue of $150 million—Jeff Bezos called the internet “the world’s waiting.” With pragmatism and optimism, we will all succeed.

Alex

Alex

Alex

Alex Brian

Brian Edmund

Edmund Cheng Yuan

Cheng Yuan Joy

Joy Beincrypto

Beincrypto Beincrypto

Beincrypto Coindesk

Coindesk Bitcoinist

Bitcoinist Cointelegraph

Cointelegraph