Written by: Research firm Kaiko Translated by: Felix, PANews

On October 9, three market makers (ZM Quant, CLS Global, and MyTrade) and some of their employees were charged with conspiracy to conduct false trading on behalf of NexFundAI tokens and crypto entities. A total of 18 individuals and entities face charges based on evidence provided by the FBI (Federal Bureau of Investigation).

This article will delve into the on-chain data of the NexFundAI token to identify false trading patterns that can be extended to other tokens and question the liquidity of certain tokens. In addition, this article will explore other false trading strategies in DeFi, how to detect illegal activities on centralized platforms, and finally study price manipulation in the Korean market.

Identifying Wash Trades in FBI Token Data

NexFundAI is a token issued by a company established by the FBI in May 2024 to uncover market manipulation in the crypto markets. The accused firms engaged in algorithmic wash trading, pump and dump schemes, and other manipulative tactics on behalf of their clients, often on exchanges like Uniswap. These practices targeted newly issued or small-cap tokens to create the illusion of an active market, attract real investors, and increase token prices and visibility.

The individuals involved confessed to the FBI investigation, and those involved clearly outlined their processes and intentions. Some even confirmed, "This is how we always make markets on Uniswap."

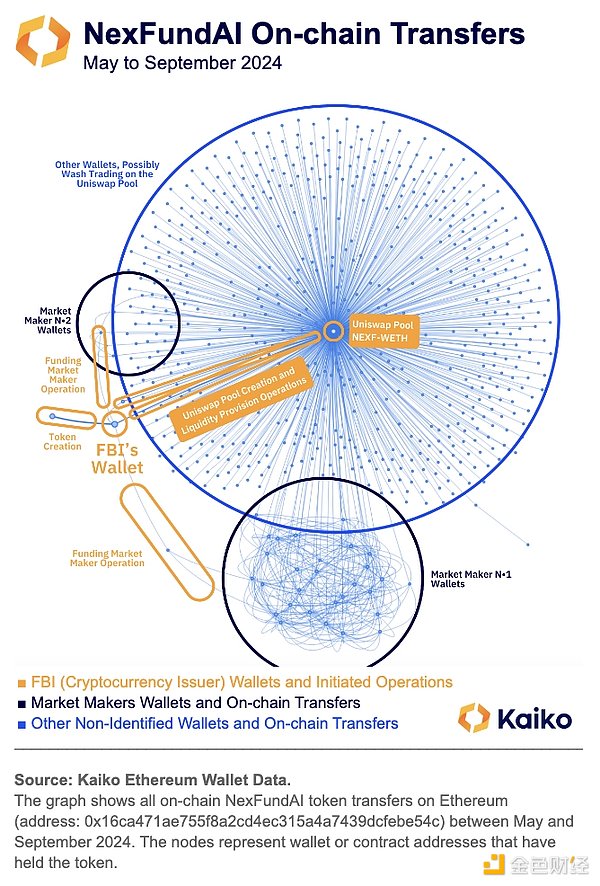

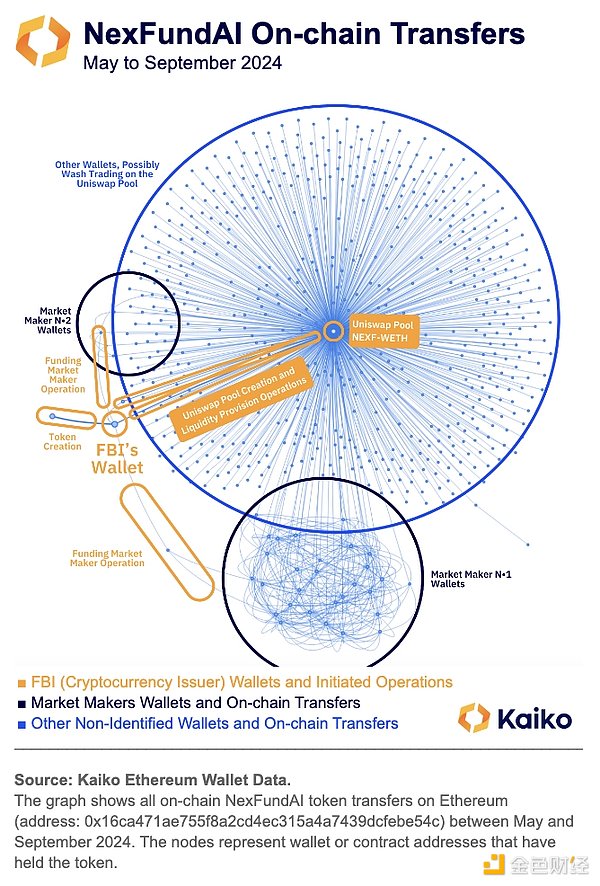

To conduct data exploration of the FBI’s fake token NexFundAI, this article examines the on-chain transfers of the tokens. The data provides complete information from issuance to every wallet and smart contract address holding these tokens.

The data shows that the token issuer funded a market maker’s wallet with the tokens, which then redistributed the funds to dozens of wallets, which are identified by the cluster highlighted in dark blue.

The funds were then used for wash trading in the token’s only secondary market, which was created by the issuer on Uniswap, identified in the center of the chart as the convergence point of almost all wallets that received and/or transferred this token between May and September 2024.

These findings further corroborate the FBI investigation. The accused company used multiple bots and hundreds of wallets to conduct fake transactions.

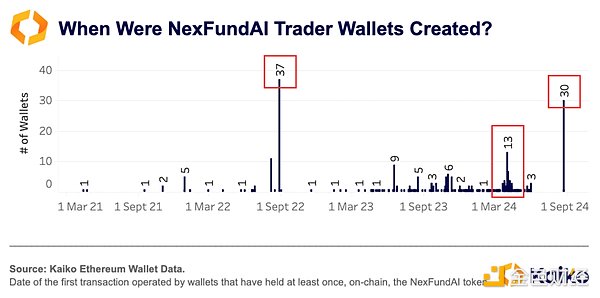

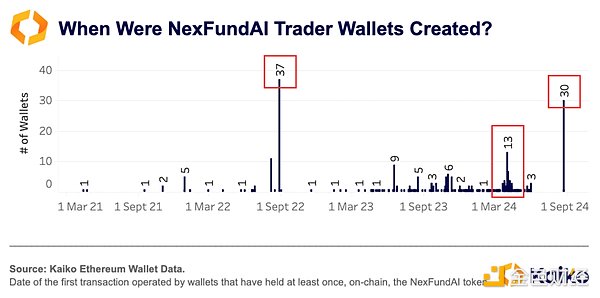

To refine the analysis and confirm the fraudulent nature of transfers from certain wallets (particularly those in the cluster), we determined the date of the first transfer received by each wallet and looked at the entire chain, not just NexFundAI token transfers. The data shows that 148 of the 485 wallets (28%) first received funds on the same block as at least 5 other wallets in the sample.

Addresses trading such an unknown token are naturally unlikely to show this pattern. Therefore, at least these 138 addresses are likely related to the trading algorithm and may be used for wash trading.

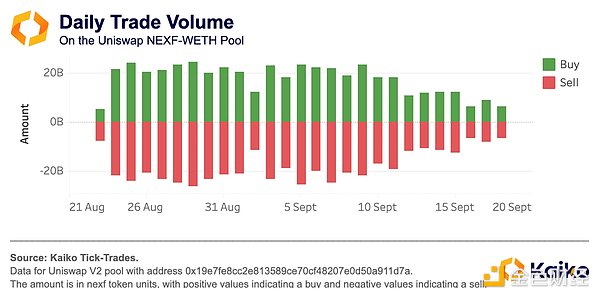

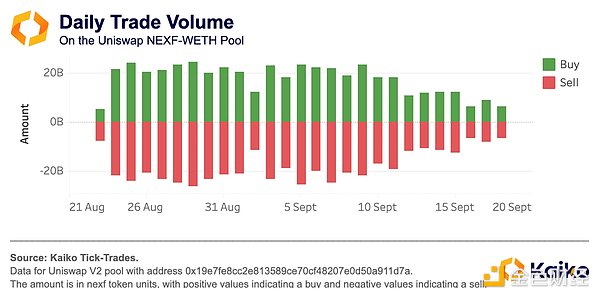

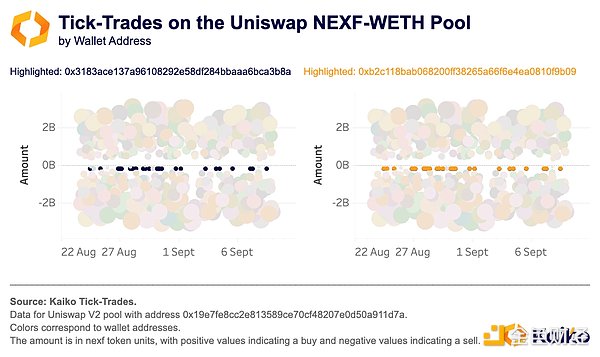

To further confirm wash trading involving this token, we checked market data for the only secondary market this token exists on. By aggregating the daily volume on this Uniswap market and comparing the buy and sell volumes, we found a striking symmetry between the two. This symmetry suggests that market makers are offsetting the total amount of all wallets engaged in wash trading on this market every day.

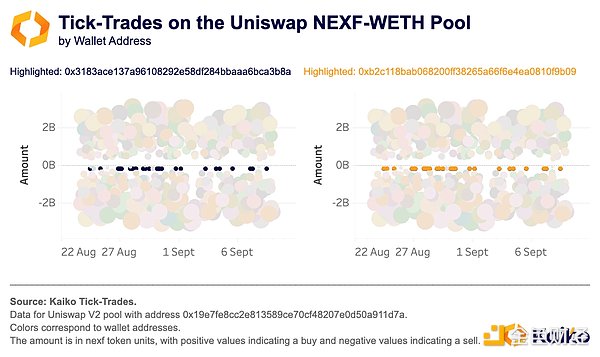

By observing individual transactions and coloring the transactions by wallet address. We found that some addresses executed exactly the same single transaction (same amount, same time point) in a month of trading activity. This suggests that these addresses are correlated and there is a fake trading strategy.

Further investigation using Kaiko’s wallet data solution revealed that both addresses, despite never interacting on-chain, were funded with WETH tokens by the same wallet address 0x4aa6a6231630ad13ef52c06de3d3d3850fafcd70. This wallet itself was funded by a smart contract from Railgun. According to the Railgun website, “Railgun is a smart contract for professional traders and DeFi users that adds privacy protection to crypto transactions.” These findings suggest that the wallet addresses are hiding secrets, such as market manipulation or worse.

DeFi fraud is not limited to NexFundAI

Manipulative behavior in DeFi is not limited to the FBI investigation. Data shows that many of the more than 200,000 assets on Ethereum DEXs lack utility and are controlled by individuals.

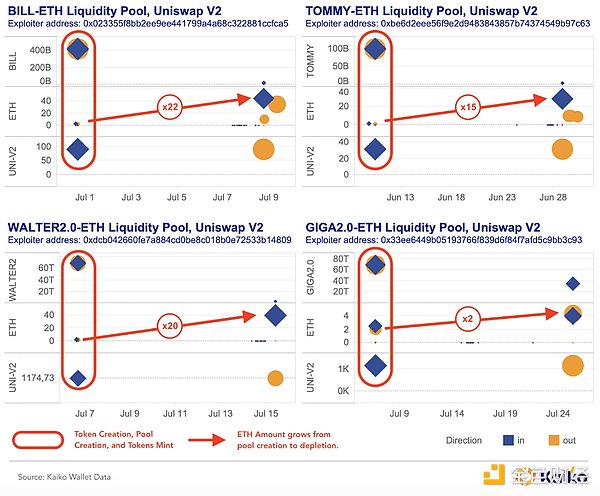

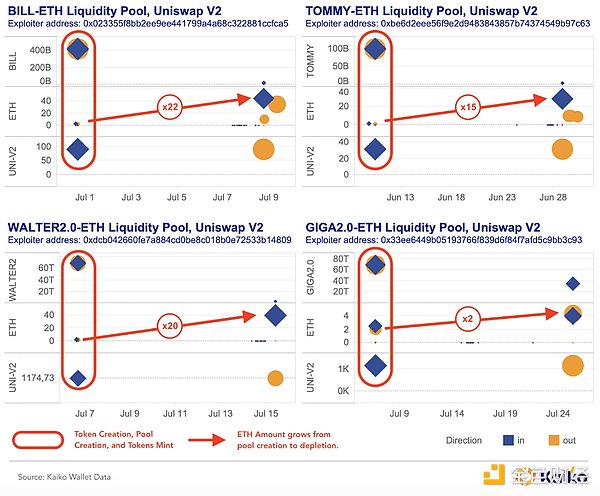

Some token issuers found on Ethereum are creating short-term liquidity pools on Uniswap. By controlling the liquidity of the pool and performing wash trading with multiple wallets, the pools are enhanced to attract regular investors, accumulate ETH, and sell their tokens. As shown, 22 times the initial ETH investment was generated in about 10 days. This analysis reveals widespread fraud by token issuers, which extends beyond the FBI's NexFundAI investigation.

Data Schema: GIGA2.0 Token Example

A user (e.g. 0x33ee6449b05193766f839d6f84f7afd5c9bb3c93) receives (and originates) the entire supply of new tokens from an address (e.g. 0x000).

The user immediately (within a day) transfers the tokens and some ETH to create a new Uniswap V2 pool. It owns all the liquidity and gets UNI-V2 tokens representing its contribution.

After an average of 10 days, the user withdraws all liquidity, destroys their UNI-V2 tokens, and collects the additional ETH earned from the pool's transaction fees.

When examining the on-chain data for these four tokens, the exact same pattern is found. This is evidence of an orchestrated manipulation through an automated and repetitive scheme with the sole purpose of profit.

Market manipulation is not unique to DeFi

While the FBI’s approach was effective in uncovering these practices, market abuse is not new to crypto, nor is it unique to DeFi. In 2019, the CEO of market maker Gotbit publicly discussed his unethical business of helping crypto projects “masquerade” and exploit the incentives of smaller exchanges to manipulate on their platforms. The Gotbit CEO and two directors were also charged in similar schemes involving multiple cryptocurrencies.

However, it is more difficult to detect such manipulation on centralized exchanges. These exchanges only display market-level order and transaction data, making it difficult to identify fake trading. However, it can be assisted by comparing trading patterns and market indicators across exchanges. For example, if the trading volume greatly exceeds the liquidity of the asset and exchange (1% market depth), it may be due to wash trading. Generally, tokens like meme coins, privacy coins, and low-market-cap altcoins often exhibit abnormally high volume-to-depth ratios.

It is important to note that the volume to liquidity ratio is not a perfect indicator, as volume can be heavily influenced by exchange initiatives designed to increase volume on an exchange, such as zero-commission campaigns.

It is possible to examine cross-exchange correlations in volume. Volume trends for an asset tend to be correlated over time across exchanges. Consistent, monotonous volumes, periods of zero volume, or differences between exchanges can all signal unusual trading activity.

For example, when studying PEPE, which has a high volume to depth ratio on some exchanges, it was noted that there was a large difference in volume trends between an anonymous exchange and other platforms in 2024. PEPE volumes on this exchange remained high and even increased in July, while PEPE volumes on most other exchanges decreased.

More detailed trading data shows that algorithmic traders are active in the PEPE-USDT market on this exchange. On July 3, there were 4,200 buy and sell orders for 1 million PEPE in a 24-hour period.

Similar patterns were seen on other trading days in July for the same trading pairs, confirming automated trading activity. For example, between July 9 and 12, more than 5,900 buy and sell trades for 2 million PEPE were executed.

Some signs point to possible automated wash trading. These signs include high volume-to-depth ratios, unusual weekly trading patterns, and repetitive orders of fixed size and rapid execution. In wash trading, a single entity places buy and sell orders simultaneously to artificially increase volume and make the market appear more liquid.

The line between market manipulation and inefficiency is blurry

Market manipulation in crypto markets is sometimes mistaken for arbitrage, where traders profit from market inefficiencies.

The "Fishing Net Pumping" in the South Korean market is an example. Traders took advantage of temporary pauses in deposits and withdrawals to artificially increase asset prices and profit. One notable example was the suspension of trading of CRV tokens on several South Korean exchanges after a hack in 2023.

When an exchange suspended deposits and withdrawals for CRV tokens, the price initially rose sharply due to a large amount of buying. However, it quickly fell as selling began. During the suspension, there were several short-lived price increases due to buying, but they were always followed by selling. Overall, there were more selling than buying.

Once the suspension ended, the price fell rapidly because traders could easily buy and sell between exchanges to make a profit. Due to limited liquidity, these pauses often attract retail traders and speculators who expect prices to rise.

Conclusion

Research on how to identify market manipulation in crypto markets is still in its early stages. However, combining data and evidence from past investigations can help regulators, exchanges, and investors better address this issue in the future. In DeFi, the transparency of blockchain data provides a unique opportunity to detect wash trading across all tokens and gradually improve market integrity.

On centralized exchanges, market data can highlight new market abuse issues and gradually align the incentives of some exchanges with the public interest. As the crypto industry develops, leveraging all available data can help reduce harmful practices and create a fairer trading environment.

Catherine

Catherine