Introduction

The mediator had just announced Facebook’s settlement: $65 million. The room was silent. Mark Zuckerberg’s lawyers waited for a response.

Most people would have taken the money and walked away. Tyler Winklevoss looked at his brother, Cameron Winklevoss, and then across the table.

“We’re taking the stock.”

The lawyers probably exchanged glances. Facebook was still private, and the stock could be worthless, and the company could fail. Cash was tangible, while stock was a gamble.

But Tyler’s response defined the next decade of their lives. They bet the entire settlement on a company that had technically stolen their idea.

When Facebook went public in 2012, their $45 million in stock was worth nearly $500 million.

The Winklevoss twins pulled off one of the most audacious moves in Silicon Valley history. They lost the battle for Facebook but made more money from it than most early employees.

In 2013, they seized the moment again and found a new opportunity.

The Birth of a Mirror Image

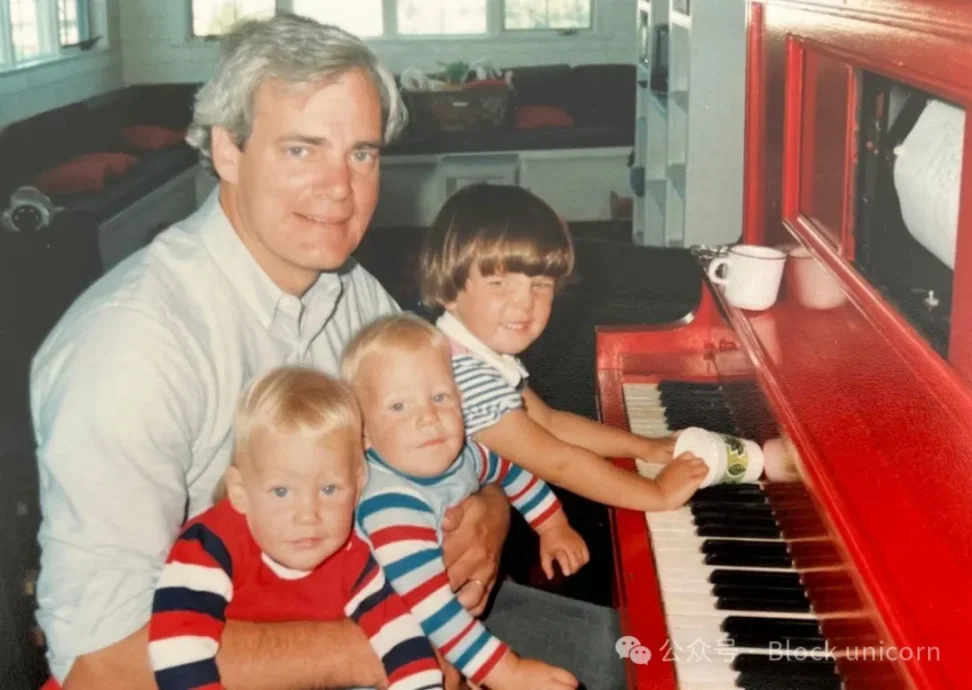

Before they became cryptocurrency billionaires or Facebook litigants, Cameron and Tyler Winklevoss were mirror images of each other, literally.

They were born on August 21, 1981, in Greenwich, Connecticut, as identical twins with one key difference: Cameron is left-handed and Tyler is right-handed. Perfect symmetry.

They were tall, athletic, and incredibly well-coordinated. At 13, they taught themselves HTML and built websites for local businesses. As teenagers, they founded their first dot-com company, creating websites for any client willing to pay.

At Greenwich Country Day School and later Brunswick School, they discovered competitive rowing and co-founded the school’s rowing program.

In an eight-man boat, timing is critical. A few tenths of a second off, and you lose. Perfect coordination requires reading your teammates, reading the water, and making split-second decisions under pressure.

They became really good. Good enough to row at Harvard, good enough to compete in the Olympics.

But rowing taught them something far more valuable than athletic accolades—the art of perfect timing and seamless collaboration.

Harvard Lab

In 2000, the Winklevoss twins entered Harvard University as economics majors with dreams of competing in the Olympics.

Cameron joined the men's varsity team, the exclusive Porcellian Club, and the Hasty Pudding Club. The brothers threw themselves into competitive rowing with an intensity that would eventually take them to international competition.

In 2004, they helped Harvard's team, nicknamed "The God Team," to a winning collegiate rowing season. They won the Eastern Sprint, the Collegiate Rowing Association Championships, and the legendary Harvard-Yale rivalry.

But an important discovery occurred beyond the water.

In December 2002, during their junior year, the twins conceived HarvardConnection, later renamed ConnectU, while researching the social dynamics of elite college life.

The idea was to create an exclusive social network for college students, starting at Harvard and expanding to other elite universities. They had a deep understanding of their generation’s needs: Students wanted to connect digitally, but existing tools were clunky and cookie-cutter.

There was only one problem: They were athletes and economics majors, not programmers.

They needed help, someone smart, someone who understood their vision.

And that’s when Mark Zuckerberg showed up.

October 2003, Kirkland Dining Hall, Harvard University.

The twins pitched their social network idea to Mark Zuckerberg.

The sophomores, computer science majors, were reportedly working on a project called Facemash, where students could rate each other’s photos.

Perfect.

They pitched their vision for HarvardConnection to Zuckerberg. He listened, nodded, asked about features and technical details, and seemed interested. They scheduled a follow-up meeting.

For a few weeks, everything went well. Zuckerberg participated in discussing ideas, discussing implementation details, and showing his commitment to the project. The twins thought they had found their programmer.

January 11, 2004. While the twins waited for their next meeting with Zuckerberg, he registered a domain name: thefacebook.com.

Four days later, instead of meeting with them, he launched Facebook.

The twins read the news in the Harvard Crimson and discovered that their programmer had become a competitor. They realized they had been tricked.

The Legal Battle

In 2004, ConnectU sued Facebook, alleging that Zuckerberg had stolen their idea, breached an oral contract, and built a competing platform using their concept.

Four years of legal battles followed. The team of lawyers grew, and the case became a sensation. But the lawsuit gave the twins a close-up look at one of the most significant technological shifts in human history.

During the legal battle, they watched Facebook take over college campuses, then expand to high schools, then open to everyone. The platform they envisioned was taking over the world, just with someone else's name.

They studied Facebook's user growth, analyzed its business model, and observed its network effects. By the time of the 2008 settlement, they understood Facebook better than almost anyone outside the company.

But their biggest rivalry took place in the courtroom, not on the water.

The twins’ decision to settle for Facebook stock rather than cash in 2008 proved to be visionary. When Facebook went public in 2012, their $45 million in stock was worth nearly $500 million.

They proved that even if the Winklevosses can lose a battle, they can win the war.

Their athletic careers ran parallel to the legal drama. At the 2007 Pan American Games in Rio, Cameron won gold in the men’s eights and silver in the men’s coxless fours. The following year, the brothers competed in the Beijing Olympics, finishing sixth in the men’s coxless doubles and becoming among the world’s top rowers.

Bitcoin Apocalypse

After Facebook's huge returns, the twins tried to become Silicon Valley angel investors. But every startup rejected them. The reason? Mark Zuckerberg would never buy a company related to the Winklevoss twins. Their money turned into "poison."

Deeply shocked, they fled to Ibiza. One night in a club, a stranger named David Azar approached them with a dollar bill and said, "A revolution."

Standing on the beach, David explained Bitcoin to them. Bitcoin is a completely decentralized digital currency, with only 21 million ever created. The twins had never heard of it. In 2012, almost no one owned one.

As Harvard economics graduates, they saw the potential of Bitcoin: digital gold, with all the properties that have historically given gold its value, but better.

In 2013, while Wall Street was still figuring out what cryptocurrencies were, the Winklevoss twins were already investing heavily.

They invested $11 million when the price of Bitcoin was $100. That was about 1% of all Bitcoins in circulation at the time, about 100,000.

Just think about it: they were Olympians, Harvard graduates, young people with endless possibilities, betting millions on a digital currency that most people associated with drug dealers and anarchists.

Their friends must have thought they were crazy.

But they had seen a dorm-room idea turn into a company worth hundreds of billions of dollars. They understood how quickly the impossible could become inevitable.

Their analysis: If Bitcoin became a new kind of money, early adopters would reap huge rewards; if it failed, they could afford to lose.

When Bitcoin hit $20,000 in 2017, their $11 million turned into more than $1 billion. They became the world’s first confirmed Bitcoin billionaires.

The pattern was becoming clear. Cameron and Tyler Winklevoss had a vision.

Building Infrastructure

The twins didn’t just buy Bitcoin and wait for it to appreciate, they started building the infrastructure that would drive mass adoption.

Winklevoss Capital provides seed money to build a new digital economy: exchanges (like BitInstant), blockchain infrastructure, custody tools, analytics platforms, and later DeFi and NFT projects. Their portfolio ranges from protocol developers (like Protocol Labs and Filecoin) to energy infrastructure for cryptocurrency mining.

In 2013, they filed the first Bitcoin ETF application with the U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC). It was an attempt that was almost doomed to fail, but someone had to take the first step. In March 2017, the SEC rejected their application on the grounds of market manipulation. They tried again and were rejected again in July 2018. But their regulatory efforts laid the foundation for other applicants. In January 2024, the spot Bitcoin ETF was finally approved, marking the fruition of the framework the twins had begun to build more than a decade ago.

In 2014, BitInstant CEO Charlie Shrem was arrested at the airport for money laundering related to Silk Road transactions, and BitInstant was forced to close. Major Bitcoin exchange Mt. Gox was hacked and 800,000 Bitcoins were lost. The infrastructure the twins invested in was collapsing, and the Bitcoin market was turbulent.

But they saw opportunity in the chaos. The Bitcoin ecosystem needed legitimate, regulated companies.

In 2014, they founded Gemini, one of the first regulated cryptocurrency exchanges in the United States. While other crypto platforms operated in a legal gray area, Gemini worked with New York State regulators to establish a clear compliance framework.

They understood that for crypto to go mainstream, it had to have institutional-grade infrastructure. The New York State Department of Financial Services granted Gemini a limited purpose trust charter, making it one of the first licensed Bitcoin exchanges in the U.S.

By 2021, Gemini was valued at $7.1 billion, with the twins owning at least 75% of the shares. Today, the exchange has total assets of over $10 billion and supports more than 80 cryptocurrencies.

Through Winklevoss Capital, they have invested in 23 cryptocurrency projects, including participating in Filecoin’s funding round in 2017 and Protocol Labs.

Instead of fighting regulators, the Winklevoss twins worked to educate them. Instead of seeking regulatory arbitrage, they built compliance into their products from the start.

Gemini’s challenges included a $2.18 billion settlement in 2024 over its Earn program. But the exchange survived and continues to operate.

The twins understand that technology alone is not enough to succeed, and regulatory acceptance will determine the fate of cryptocurrencies.

In 2024, they each donated $1 million in Bitcoin to Donald Trump’s presidential campaign, positioning themselves as advocates for crypto-friendly policies. Their donations exceeded federal contribution limits and were partially refunded, but they have made their stance clear.

The twin brothers have been outspoken critics of the SEC’s overly aggressive enforcement approach under Chairman Gary Gensler. Their regulatory battles have involved both personal and professional development. The SEC’s lawsuit against Gemini directly challenges their business model. In June 2025, Gemini confidentially filed for an IPO.

Current Record

Forbes currently values the brothers at $4.4 billion, with their combined net worth of approximately $9 billion, with Bitcoin assets constituting the largest portion of their wealth.

Their crypto assets include approximately 70,000 Bitcoins, valued at $4.48 billion, as well as significant holdings in Ethereum, Filecoin, and other digital assets.

Gemini remains one of the most trusted cryptocurrency exchanges in the world, with institutional-grade security features and regulatory compliance. The exchange’s IPO filing marks an important step toward mainstream financial market integration.

In February 2025, the twins became part-owners of Real Bedford Football Club, an eighth-tier English football team, investing $4.5 million.

Partnering with crypto podcaster Peter McCormack, they are trying to push the semi-pro team into the Premier League.

Their father Howard also donated $4 million in Bitcoin to Grove City College in 2024, the school's first Bitcoin donation, to fund the new Winklevoss School of Business.

The twins personally donated $10 million to Greenwich Country Day School, the largest alumni donation in the school's history.

They have publicly stated that they will not sell Bitcoin even if its market value reaches the level of gold, demonstrating their belief that Bitcoin is not just a store of value, but a fundamental reinvention of money.

The Harvard Crimson revealed Mark Zuckerberg's betrayal, and a dollar bill on an Ibiza beach ignited a revolution - these two moments happened before and after they learned to see what others did not see. For years, brothers Cameron and Tyler Winklevoss were thought to have missed the party. Turns out, they just made it to the next big party early.

JinseFinance

JinseFinance

JinseFinance

JinseFinance Catherine

Catherine Beincrypto

Beincrypto cryptopotato

cryptopotato dailyhodl

dailyhodl Beincrypto

Beincrypto Beincrypto

Beincrypto Cryptohayes

Cryptohayes Ftftx

Ftftx Ftftx

Ftftx