Source: Grayscale; Compiled by Wuzhu, Golden Finance

Abstract

Bitcoin is able to serve as a global digital currency system because of Bitcoin mining: a competitive process for updating the blockchain and coordinating economic incentives across the network. Today, the Bitcoin mining network is so large that it generates more than 700 trillion "hashes" per second. [1]

Bitcoin miners earn income from issuing new Bitcoins and network transaction fees. They also have to cover the costs of capital equipment, electricity, and other operating costs. Many miners also hold Bitcoin on their balance sheets, and a growing number are diversifying into artificial intelligence (AI) and high-performance computing (HPC) services.

Grayscale Research estimates that Bitcoin mining accounts for only 0.2% of global electricity use; clean energy may also account for a higher share of electricity consumed by Bitcoin mining than in other industries. Bitcoin mining may help accelerate environmental goals, particularly in areas such as methane emissions.

Bitcoin is a decentralized, open network of computers worth $2 trillion. [2] This modern miracle is made possible by Bitcoin mining: network participants compete for the right to add the next block to the blockchain and receive a reward. Today, Bitcoin miners operate at an incredible scale, transforming real resources into digital security. The computing power used to protect the Bitcoin blockchain is its digital “vault door”: an autonomous network of computers that serves as the mechanism for a global digital currency system. The technical expertise, capital expenditures, and ongoing operating expenses required to operate Bitcoin mining facilities, as well as the highly competitive nature of the business, help keep the Bitcoin network decentralized and costly to attack.

Investing in publicly traded Bitcoin miners can earn revenue from block production, as well as potential revenue growth from rising network transaction fees over time. In practice, most publicly traded Bitcoin miners follow different business models, with many retaining mined Bitcoin on their balance sheets or even purchasing Bitcoin on the open market. Bitcoin miners have also begun to diversify, operating data centers for AI and high-performance computing (HPC).

A Modern Marvel

Although technically complex, the process of Bitcoin mining is conceptually simple. Specialized computers compete to guess a random number, and the machine that guesses the correct number first is awarded the right to update the blockchain ("mine a block"). The winning miner is awarded newly issued Bitcoins and transaction fees ("block reward"). [3]

There are no shortcuts in this race—for example, there are no algorithms that can help find the right number faster—Bitcoin miners compete by brute force. The process can be thought of as a game of chance. Miners keep guessing until they find the right solution—like rolling a multi-sided die until the desired number comes up. The probability of winning is therefore a function of the number of guesses (“rolls”) a miner can make per second. The operator with the most machines and/or the most efficient machines will make the most guesses and have the best chance of winning a block reward.

Technically speaking, the winning result is not just the random number, but the “hash value” of that number combined with other data. In computer science, a hash function is a mathematical operation that converts arbitrary data into a string of letters and/or numbers, called a hash value. For example, using the same hash function in the Bitcoin network, the word “Bitcoin” hashes to:

b4056df6691f8dc72e56302ddad345d65fead3ead9299609a826e2344eb63aa4

Thus, the purpose of Bitcoin miners is to generate hashes quickly: guess a random number, calculate its hash (combining the random number with other data), and then check whether it is correct.

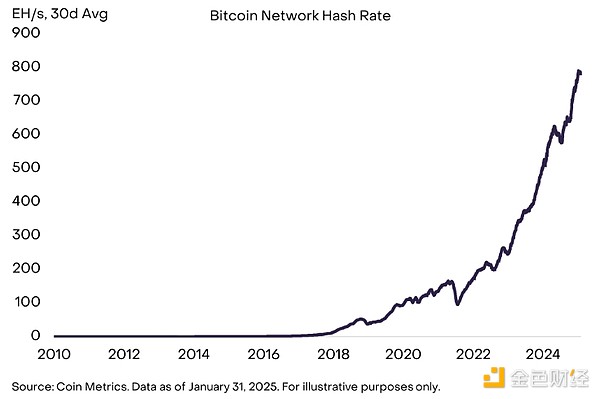

Today, there are an estimated 5 to 6 million Bitcoin mining machines[4] generating hashes at an astonishing scale (Figure 1). In total, Bitcoin miners have generated an average of 765 exahashes per second (EH/s) over the past 90 days. [5] An exahash is equal to one quadrillion (10^18) hashes. So, to put it simply, the average Bitcoin miner guesses a random number and calculates its hash over 700 quadrillion times per second. To put that number in context, it’s estimated that there are about 7.5 quadrillion grains of sand and 10 quadrillion insects alive on Earth. [6]

Figure 1: Bitcoin miners mass-produce hashes

Generating all those hashes is expensive—and that’s the point. To compete for the rewards, mining operators need to purchase specialized machines and other hardware, and pay for ongoing electricity and maintenance costs. Thus, by generating the correct hash, miners provide a “proof of work”: proof that they have expended economic resources and that they can be trusted to update the blockchain.

Attacking Bitcoin would mean disrupting the existing Bitcoin mining industry. In theory, if a malicious actor controlled 51% of the network’s hash rate, and thus could mine a majority of blocks, they could disrupt the network (for example, by double-spending bitcoins or censoring certain transactions). In one paper, researchers estimated that as of February 2024, the cost of a one-hour 51% attack on the Bitcoin network would be between $5 billion and $20 billion (depending on how the attacker acquires the mining machines). [7] In practice, no actor has an economic incentive to expend these resources, and in any case the network has other defenses besides mining. [8]

Bitcoin Mining

Bitcoin miners earn a reward equal to the reward for mining a new block, and they also need to pay for the electricity to run their machines and generate hashes (as well as possible other operating expenses such as maintenance, mining pool fees, etc.). Therefore, the goal of Bitcoin miners is to generate the most hashes per second at the lowest possible cost.

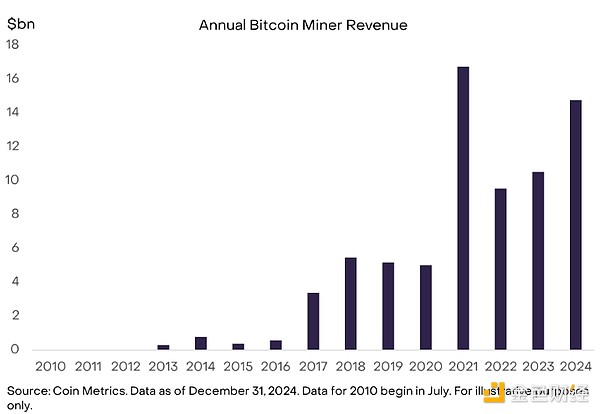

In 2024, miners will have earned a total of about 230,000 Bitcoins, worth nearly $15 billion (at current prices). [9] This is about 19 times more than in 2014, with a compound annual growth rate of 34% (Exhibit 2).The rate at which new Bitcoins are issued decreases every four years, an event known as the Bitcoin halving. Despite the decline in issuance in bitcoin terms, mining revenue has increased over time due to the appreciation of the bitcoin price in U.S. dollar terms. In the future, growth in mining revenue could come from rising bitcoin prices and/or growth in network transaction fees.

Figure 2: Bitcoin mining revenue growth over time

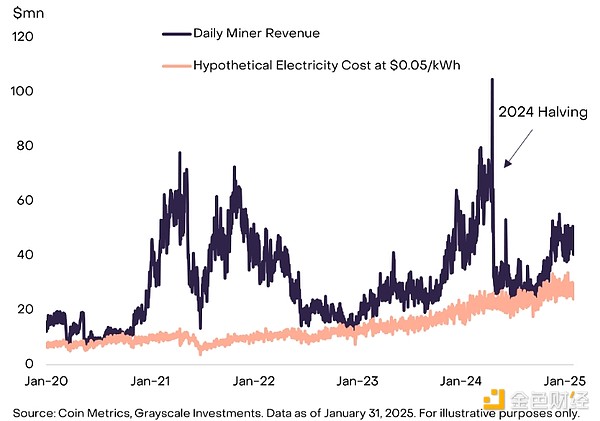

Miners incur operating expenses, primarily in the form of electricity required to run their machines. [10] Each operator negotiates its own power purchase agreement, and these agreements vary widely around the world. For the purposes of this heuristic analysis, we can create a simplified picture of the overall economics of bitcoin miners by using an assumed cost of electricity and ignoring other costs. For example, Exhibit 3 compares Bitcoin miners’ revenues to an estimated total electricity cost assuming an electricity price of $0.05 per kilowatt-hour (kWh). The difference between revenues and electricity costs can be viewed as a simplified measure of miners’ operating margins. Miners benefit when the dollar value of block rewards increases, and lose when the dollar price of produced hashrate increases.

Exhibit 3: Miner operating margins reflect the difference between block rewards and electricity costs

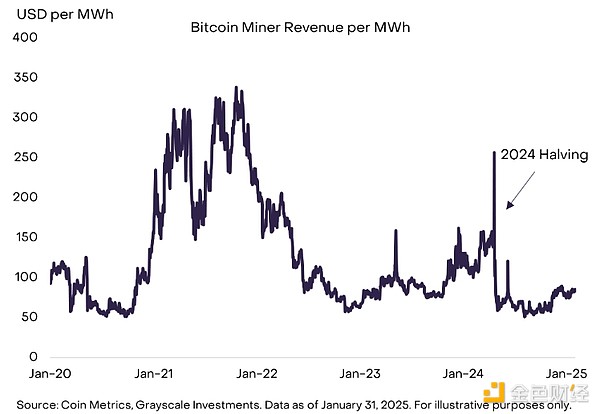

Given the differences in electricity costs faced by miners around the world, a more intuitive measure might be the dollar value received for a given amount of electricity consumed—for example, miners’ revenue per megawatt-hour (MWh). Mining industry participants often refer to the closely related concept of “hash price,” which is calculated as the ratio of daily miner revenue to the network hash rate. While the concepts are very similar, hash price will tend to decline as miners become more efficient. Therefore, the ratio of miner revenue to electricity consumption may more accurately reflect the changes in mining economics over time. Figure 4 shows Bitcoin miner daily revenue per megawatt-hour. This estimate has remained largely stable over the past two years, although there has been significant fluctuations around the 2024 halving.

Figure 4: Miners’ revenue per MWh has remained relatively stable over the past two years

Investing in Bitcoin Miners

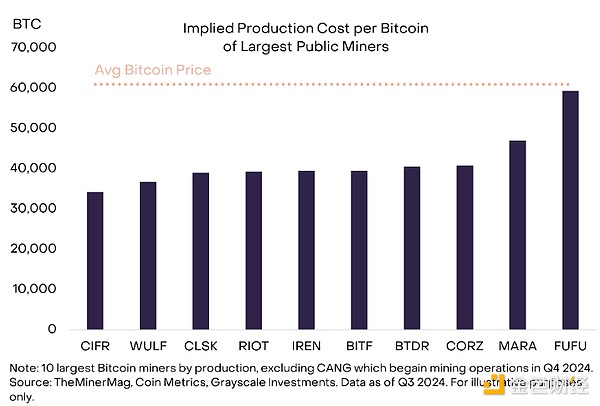

Investing in publicly traded miners’ shares provides exposure to the Bitcoin economy through stock market instruments. Bitcoin miners’ business models may be increasingly diverse, but all miners engage in the core business of producing hashrate, mining blocks, and earning block rewards. Due to differences in electricity costs, non-electricity operating expenses, and other factors[11], each miner receives block rewards at a different effective price. In the third quarter of 2024, the largest publicly traded miners produced Bitcoin at an average cost of $34,000 to $59,000 (Exhibit 5). This compares to an average price of $61,000 for Bitcoin during the quarter.

Figure 5: Production costs vary among miners

Bitcoin miners hold Bitcoin on their balance sheets in different ways. Some miners liquidate block rewards immediately, some retain them, and some even purchase additional Bitcoin on the open market. Of course, differences in balance sheet policies can have a significant impact on the relative financial performance of listed miners when the price of Bitcoin changes (Figure 6). That being said, many factors influence the risk profile of an individual miner, and those miners with relatively high Bitcoin balance sheet holdings are not necessarily riskier than those who liquidate block rewards. Figure 6: Some miners hold Bitcoin on their balance sheets Recently, Bitcoin miners have begun to expand into other AI and high-performance computing (HPC) services, which have rapidly growing demand for data center infrastructure. For example, Goldman Sachs research[12] estimates that data center electricity demand (excluding cryptocurrency) could grow by 160% between 2023 and 2030. Bitcoin miners may have a competitive advantage in supplying the AI/HPPC market because they already have access to low-cost electricity and related infrastructure. In early 2024, Core Scientific, the third largest publicly traded miner by market capitalization, announced a long-term contract with CoreWeave, a provider of specialized AI infrastructure services. [13] Since the Core Scientific/CoreWeave deal was announced in June 2024, several other publicly traded miners have taken steps to move into the AI/HPC space.

Bitcoin Mining and Sustainability

Bitcoin mining consumes real economic resources—electricity—to create decentralized digital security. Bitcoin’s success as a digital currency system means that mining now consumes a significant amount of electricity. Bitcoin is a unique energy consumer that already uses a significant portion of clean energy resources, and Grayscale Research believes it can make a positive contribution to the green energy transition over time.

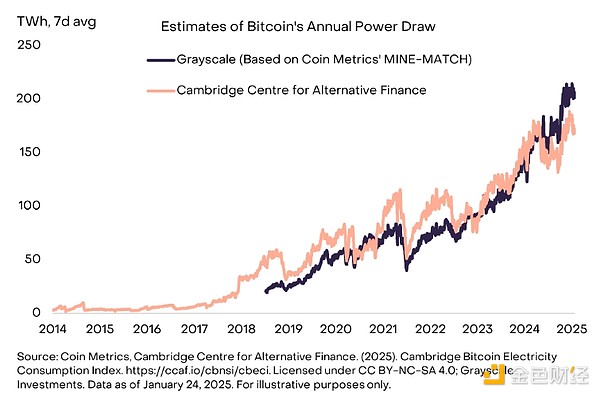

Using data from Coin Metrics’ MINE-MATCH algorithm, we estimate that the Bitcoin network consumed about 175 terawatt hours (TWh) of electricity over the past 12 months. [14] This is comparable to estimates from the Cambridge Centre for Alternative Finance (Figure 7). Based on data for 2023 (the latest available year), Bitcoin’s energy consumption accounts for 0.2% of total global electricity consumption (taking into account power losses during transmission). [15] According to the Cambridge Centre for Alternative Finance, data centers consume about 200 TWh of electricity per year, and projections suggest that data center energy consumption is likely to rise due to the use of AI models. [16]

Figure 7: Bitcoin mining consumes electricity to create digital security

Bitcoin is a unique energy consumer compared to typical residential or commercial users. Bitcoin mining is modular and portable, location-independent, interruptible, and highly sensitive to changes in electricity prices. As a result, miners can often operate in locations where clean energy resources are cheap. It is estimated that approximately 50%-60% of the electricity used by the Bitcoin mining industry comes from sustainable energy sources (including nuclear power). [17] For the United States and the world as a whole, the share of sustainable electricity generation is approximately 40%. [18] Using data from 2023 (the latest available year), and assuming a sustainable share of 50%-60% for Bitcoin electricity consumption, we estimate that Bitcoin mining accounts for 0.2%-0.3% of global electricity generation-related CO2 emissions. [19]

Grayscale Research argues that Bitcoin mining could help accelerate the adoption of renewable energy generation in the coming years. Due to its unique properties, Bitcoin mining incentivizes investment in renewable energy infrastructure development, particularly in locations without transmission to major hotspots. Bitcoin mining can also help stabilize grid demand—which would otherwise fluctuate based on consumption patterns and weather—as it does in the Electric Reliability Council of Texas (ERCOT) system. [20] Additionally, startups like Sustainable Bitcoin Protocol have created market-based mechanisms to incentivize clean energy use and reward efforts to reduce methane emissions. Tackling methane emissions could be a particularly important way for Bitcoin miners to contribute to environmental goals. Methane is released by flaring gas or burning natural gas produced by oil production. Companies like Crusoe Energy have developed ways to capture excess natural gas rather than releasing it, then convert it into electricity and power Bitcoin miners.

The growth in technology use will create a huge demand for electricity production in the coming years - from digital assets, artificial intelligence, and other industries. Grayscale believes that Bitcoin contributes to the health of the global power infrastructure and is uniquely positioned to help accelerate the transition to renewable energy compared to many other industries.

Notes

[1] Source: Coin Metrics. Data as of January 31, 2025.

[2] Source: Coin Metrics. Data as of January 31, 2025.

[3] This number is called a “nonce” (a number used only once) and is not purely random. See, for example, “The Mystery of Bitcoin’s Nonce Pattern”, BitMEX Research, 2019.

[4] Source: Grayscale Research calculations based on reported network hashrate and estimates of average miner productivity. For the latter, we use a central estimate of 125 TH/s based on Coin Metrics’ MINE-MATCH data and analysis of individual mining machine profitability at different combinations of hash price and electricity price.

[5] Source: Coin Metrics. Data as of January 31, 2025.

[6] Sources: “Which is greater, the number of grains of sand on Earth or the number of stars in the sky?”, NPR, September 2012; “Insect Populations (Species and Individuals)”, Smithsonian Institution.

[7] Nuzzi, Waters, and Andrade, “Breaking BFT: Quantifying the Costs of Attacking Bitcoin and Ethereum.” February 15, 2024.

[8] See, for example, “Analyzing Bitcoin Consensus: The Risks of Protocol Upgrades”, Ren Crypto Fish, Steve Lee, and Lyn Alden, November 2024.

[9] Source: Coin Metrics.

[10] At any given time, there are many different types of mining machines in operation. Data provider Coin Metrics has developed technology to identify the types of machines that are actively contributing hashrate to the network. We use this data to estimate power consumption and the number of active machines on the network.

[11] For example, miners may incur other costs, such as mining pool fees, and revenue may vary based on fee income for a particular block.

[12] Source: “Generational Growth – The Global Power Surge for AI/Data Centers and Its Implications for Sustainability,” Goldman Sachs, April 30, 2024.

[13] Source: “Core Scientific Signs 12-Year Deal with AI Firm for $3.5B in Total Revenue,” The Block, June 4, 2024.

[14] For the 365 days ending January 31, 2025, this approach implies an annualized power consumption of 177.8 TWh; this should be viewed as an estimate with significant uncertainty.

[15] Source: Grayscale calculations based on data from the Institute for Energy Research’s Statistical Review of World Energy and the Cambridge Centre for Alternative Finance.

[16] Source: Cambridge Centre for Alternative Finance; “Carbon Emissions from AI and Cryptocurrencies Are Surgein’; Tax Policy Can Help”, Shafik Hebous and Nate Vernon-Lin, IMF Blog, August 15, 2024.

[17] Source: See, for example, Daniel Batten’s Bitcoin Energy and Emissions Sustainability Tracker and “Bitcoin Mining Council Survey Confirms Year-over-Year Improvements in Sustainable Power and Technology Efficiency”, Bitcoin Mining Council, August 2023.

[18] Source: Grayscale calculations based on data from the Institute for Energy Research’s Statistical Review of World Energy.

[19] Source: Grayscale calculations based on data from the Institute for Energy Research’s Statistical Review of World Energy.

[20] Source: U.S. Energy Information Administration.

Brian

Brian

Brian

Brian Joy

Joy Brian

Brian Kikyo

Kikyo Joy

Joy Brian

Brian Joy

Joy Joy

Joy Kikyo

Kikyo Alex

Alex