Author: Daniel Barabander, Investment Partner at Variant Fund; Translated by AIMan@金色财经

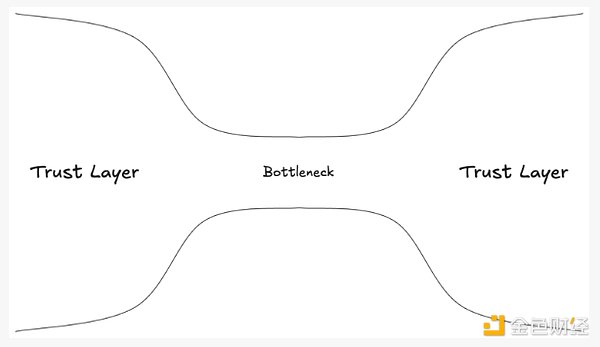

One of the biggest opportunities for cryptocurrency is to disrupt what I call “hourglass markets”—markets where value must move from one trust layer to another, but can only do so through a narrow bottleneck of intermediaries.

While these types of markets can form anywhere, they are particularly common in cross-border transactions because political sovereignty prevents countries from merging their domestic trust layers into a single global trust layer.

The best place to observe these dynamics is in the payments space. Imagine buying groceries and handing the cashier a personal IOU for $50, payable in 30 days. You'd likely be laughed at by the clerk. The fundamental problem is settlement risk: you're taking the groceries now, promising to pay later. Since the grocery store doesn't know whether you'll honor your obligations, it won't accept your IOU as payment. However, if you and the supermarket both have accounts at Bank A, the transfer of value becomes much easier. This is because you both trust Bank A. So when Bank A updates its ledger, debiting your account for $50 and debiting the supermarket's account for $50, each participant confirms that the transaction has been settled. We solved the settlement problem by stacking layers of trust and passing them up to a shared trust layer: Bank A. The problem arises again when the participants have different banks. Bank A doesn't trust Bank B's ledger for the same reason the supermarket doesn't trust yours. But we solve this problem again by stacking and aggregating trust at another shared trust layer: the central bank. Let's say that we open accounts for Bank A and Bank B at a government-run central bank. To complete an inter-bank transfer, the central bank debits Bank A's account and credits Bank B's account. Thus, the default approach to scaling payments is to stack and aggregate trust from decentralized trust layers into a centralized trust layer. But when things move across borders, we face a fundamental coordination problem that makes stacking and aggregation infeasible. There is no single "central" bank to settle cross-border payments, because no country would trust another to operate a global central bank; each nation maintains its own political and economic sovereignty (not least because each sovereign issuing state is the source of truth for its own currency). Our settlement problem is once again raised. Because banks in different jurisdictions don't share a unified settlement layer, they rely on bilateral agreements to bridge the gap between their disjointed trust layers. In effect, Bank C in Argentina must open an account with Bank B in the United States. But because Bank C doesn't trust Bank B, it must establish that trust through a legal contract so that transfers on Bank B's books are considered final. These bilateral agreements are costly, requiring disclosure, compliance with AML/CFT regulations, collateral, and audits. The institutions providing these services are known as correspondent banks, as they maintain correspondent accounts at each other's banks. Only a handful of banks are large enough to command the trust and operate at the scale required to absorb the high costs of these agreements. In fact, as of 2019, just eight banks processed over 95% of euro-denominated cross-border transactions. This handful of banks monopolizes this interoperability function, creating anticompetitive bottlenecks that restrict the flow of funds between layers of trust. Take remittances, a nearly $1 trillion market: the average cost of sending remittances is approximately 6%, and the average time to arrival often takes a day or more, largely due to the inefficiencies created by this bottleneck. It's an hourglass-shaped market. What about cryptocurrencies? Cryptocurrencies solve the settlement problem by creating a ledger controlled by no one person and building a shared trust layer whose validity is recognized by all participants. Tokens on a blockchain act like digital bearer assets: whoever controls the key is deemed the owner. This democratizes the holding and transfer of value because transactions can be settled without trusting the sender of the asset. Therefore, participants can transfer assets peer-to-peer. This is precisely why stablecoins have such strong product-market fit in cross-border payments. By enabling peer-to-peer transfers of US dollars, cryptocurrencies allow participants to bypass the bottleneck of this hourglass market, significantly improving the efficiency of cross-border payments. While in some ways this feels like a "cryptocurrency primer," this framework allows us to zoom in and see the natural, even inevitable, formation of hourglass markets in cross-border transactions. This is because the principle of political sovereignty remains a persistent reconciliation issue, hindering the integration of disjointed trust layers across different countries. Wherever we see this pattern, cryptocurrencies offer the potential to bypass the inevitable bottlenecks and break the mold. Stocks are another example of a cross-border hourglass market. Ownership of publicly traded company stock is very similar to our banking system. In the United States, trust is accumulated and passed on through brokers and custodians, which then pass it on to a central securities depository (CSD) called the DTCC. Europe follows a similar model, with trust ultimately passing on to its own clearinghouses, such as Euroclear in Belgium and Clearstream in Luxembourg. But just as there is no global central bank, there is no global CSD either. Instead, these markets are connected through a small number of large intermediaries using costly bilateral agreements that traverse layers of trust, creating an hourglass market. As a result, cross-border stock trading remains predictably slow, expensive, and opaque. Similarly, we can use cryptocurrencies to democratize ownership, bypassing bottlenecks and enabling participants to directly own these securities regardless of their location.

Beyond Cross-Border

Hourglass markets are everywhere once you know how to look. In fact, even within cross-border payments, there are arguably two hourglass markets: the one I focus on in this article—cross-border fund flows—and currency exchange. For similar reasons, the foreign exchange market exhibits an hourglass shape, with a small group of global transaction banks—connected by a dense network of bilateral trade agreements and privileged access to settlement systems like CLS—sitting at the bottleneck of national currencies' disconnection. Projects like OpenFX are now using cryptocurrencies to circumvent this bottleneck.

While cross-border transactions are the easiest way to identify hourglass markets, these markets are not specific to geographic location. Given the right conditions, they can emerge anywhere. Two markets stand out:

Assets with Cross-Tier Utility.Hourglass markets require assets with cross-tier utility; otherwise, participants have no reason to move them, and bottlenecks don't form. For example, the Kindle Bookstore and the Apple Bookstore can be viewed as disjointed trust networks—each issues IOUs for digital book licenses, but neither has an incentive to make its IOUs compatible with the other's network. Since Kindle books have no utility for Apple, there's no reason to transfer them across these layers. Without such utility, intermediaries don't emerge to facilitate flows, and hourglass markets don't form. In contrast, assets with broad or universal utility, such as currencies or speculative instruments, are more likely to form. Regulatory fragmentation. Cross-border bottlenecks can be described as the fragmentation of trust layers caused by differing regulatory regimes, but the same effect can also occur within a single jurisdiction. For example, in domestic securities markets, cash is typically settled through real-time gross settlement (RTGS), while securities are settled through central depositories (CSDs). This leads to high costs of coordination through brokers, custodians, and other intermediaries—a domestic mechanism that the Bank for International Settlements estimates costs banks $17 billion to $24 billion annually in transaction processing. While writing this article, I've heard a range of other potential hourglass markets, including syndicated loans, commodity futures, carbon trading, and more. Even in the cryptocurrency space, many similar markets exist, such as fiat-to-crypto on-ramps, certain bridges between blockchains (e.g., wrapped BTC), and interoperability between different fiat-backed stablecoins. Builders who can discover these hourglass markets will be best positioned to leverage the principles of cryptocurrency and transcend systems rooted in bilateral agreements.

Anais

Anais