Source: Industrial Bank Research, Author: Zhang Lihan, Guo Yuwei, Lu Zhengwei

Abstract

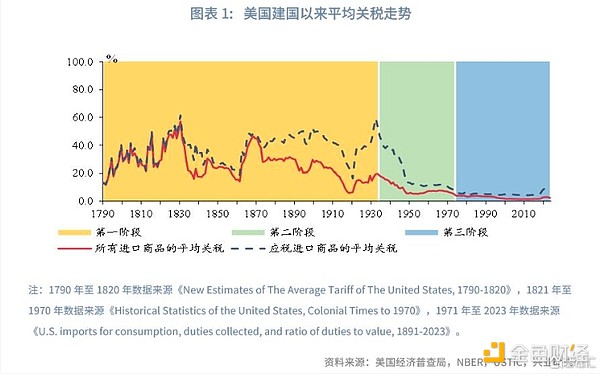

The United States will see a rise in trade protectionism every few decades. The purpose of trade policy can be attributed to the three "Rs": revenue, restriction, and reciprocity. Based on this, the trade policy of the United States since its founding can be divided into three stages:

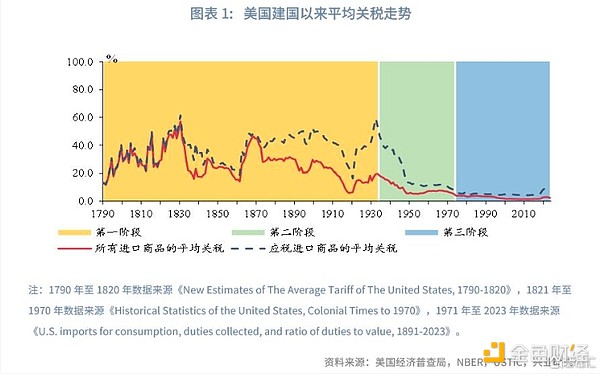

The first is the period of trade protectionism from 1789 to 1933, during which tariffs fluctuated greatly. Between the American War of Independence and the Civil War, the United States was still in the early stages of industrialization. Protecting infant industries and increasing fiscal revenue were the main reasons for the United States to raise tariffs. From 1863 to 1933, with the diversification of tax sources, protecting industries and defending the gold standard became the main reasons for the United States to raise tariffs. The second is the period of free trade from 1934 to 1973, when the US industry had matured, promoting exports through reciprocal agreements became the main goal, and tariff levels dropped significantly. However, in the early 1970s, when the relative strength of the US industry weakened and the balance of payments was unbalanced, trade protectionism rose again. Third, since 1974, the United States has entered a new stage of trade policy with low tariffs but complex non-tariff barriers.

The rise and fall of U.S. trade protectionism shows that: first, protecting domestic industries, improving international payments, and reducing fiscal deficits are the unchanging motivations of trade protectionism. Second, the high tariff policy that goes against the historical trend is doomed to be unsustainable, and with the deepening of globalization, the duration of high tariffs is getting shorter and shorter. The Tariff Act, the Smoot-Hawley Tariff Act, and Nixon's high tariffs ushered in a turning point after 5 years, 4 years, and less than 1 year respectively. Only the Dingley Tariff Act coincided with the surge in global gold production and lasted for a long time. Third, the direct reasons for the end of high tariffs are more complicated. The dissatisfaction of the American people with high prices, the opposition of domestic interest groups, and the countermeasures of trading partners may all lead to a turning point in trade protection. Fourth, the turning point of tariff policy is usually accompanied by fundamental changes in the monetary system, such as a sharp depreciation of the US dollar or a significant increase in gold production. This means that there may be a trade-off between the monetary system and tariffs, and the excessive imbalance of international payments must be corrected.

I. Review of the major tariff bills in the United States

Irwin (2017) believes that the purpose of the US trade policy in history can be attributed to three "Rs": revenue, restriction, and reciprocity. Among them, in terms of revenue, tariffs can increase government fiscal revenue; in terms of restriction, tariffs can limit foreign imports to achieve the purpose of protecting domestic industries; in terms of reciprocity, reaching tariff reciprocity agreements with foreign countries can promote US exports. Based on the above three purposes, looking at the history of the United States since its founding, the attitude of the United States on tariffs and trade issues can be mainly divided into three stages.

1.1 The period of trade protectionism

Between 1789 and 1933, the United States was in a stage of gradual industrialization and economic take-off. In order to protect domestic industries, trade protectionism prevailed in the United States. During this period, reasons such as raising military funds and defending the gold standard also strengthened the tendency of trade protectionism in the United States. Economic depression and rising prices may be the motivation for reducing tariffs, and a more flexible exchange rate system (abandoning the gold standard) paved the way for reducing tariffs.

1.1.1 From the War of Independence to the Civil War: Protecting infant industries and raising military expenses

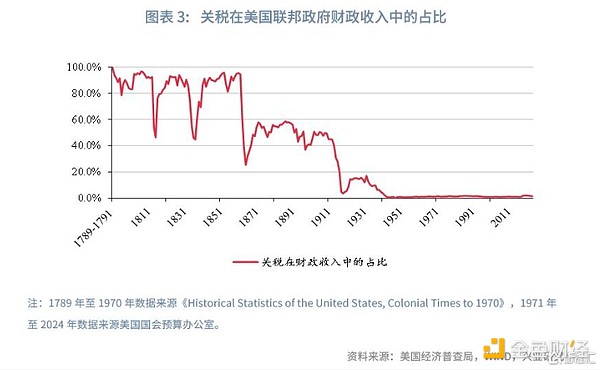

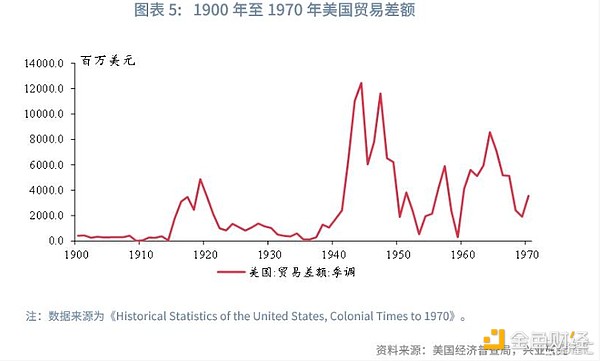

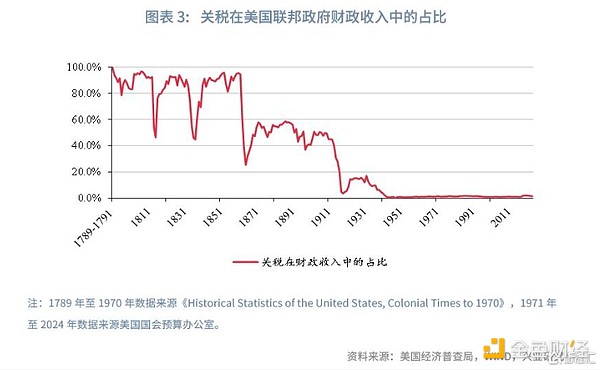

From 1789 to 1862, roughly corresponding to the period between the American War of Independence and the Civil War, the United States was still in the early stages of industrialization. Protecting infant industries and increasing fiscal revenue were the main reasons for the United States to increase tariffs. During this period, tariffs usually contributed about 90% to the US fiscal revenue, and the United States implemented a comprehensive tariff policy mainly during this period. However, we can observe that the US tariff level changed greatly during this period. This is because tariffs, while protecting the development of US industry, hurt US agricultural exports, thus touching the "cake" of the US Southern interest groups.

In the 1820s, the US Industrial Revolution began to accelerate. In 1818, James Monroe, the fifth president of the United States, proposed in his message to Congress that "tariffs should especially protect the nascent manufacturing industry and industries closely related to national independence". In 1828, in order to protect the development of American industry, the Adams administration passed a tariff law, raising the average tariff level of taxable products in the United States to 44.8%. This tariff law was later called the "Abominable Tariff Law" by the interest groups in the southern United States.

From the impact of the tariff law, the tariff law intensified the contradictions between the interest groups in the north and south of the United States. There is a conflict of economic interests between the industrial states in the north and the agricultural states in the south of the United States. The northern states tend to have high tariffs to protect local industries, while the southern states rely on exporting agricultural products and tend to have low tariffs to promote exports. Against the opposition of the Southern interest groups, Congress lowered the tariff rate twice in 1830 and 1832. However, after the Jackson administration signed the Tariff Act of 1832, South Carolina declared that the Tariff Acts of 1828 and 1832 were unconstitutional and threatened to withdraw from the federal government.

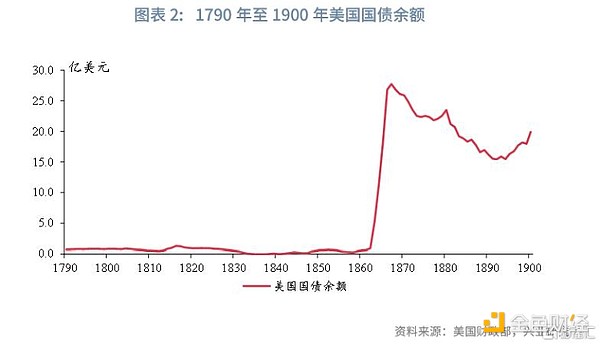

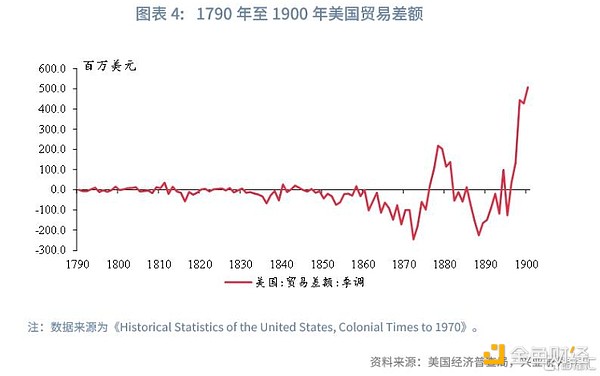

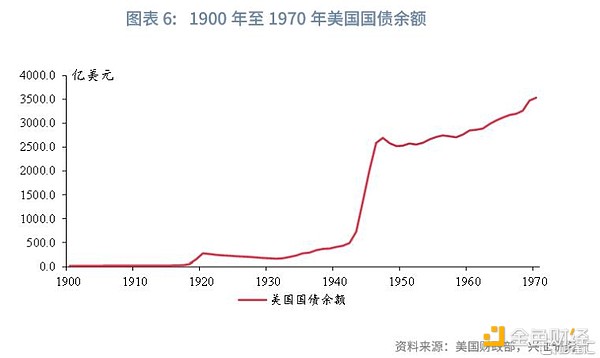

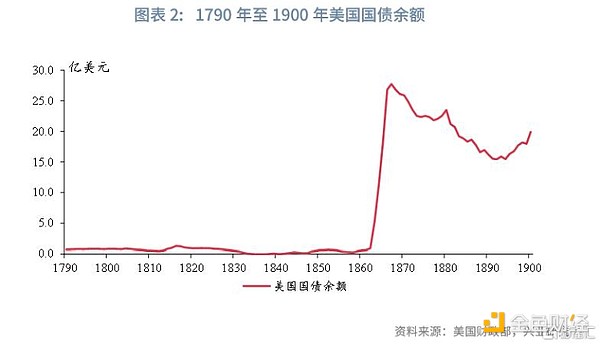

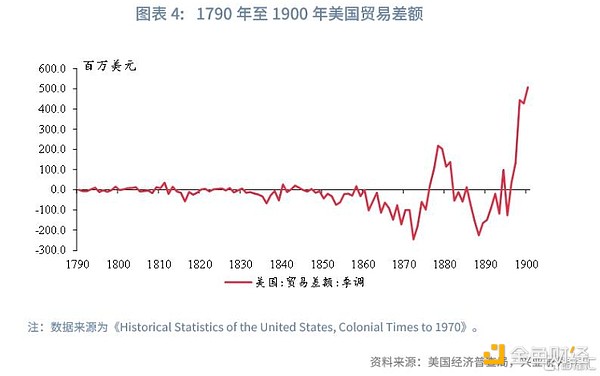

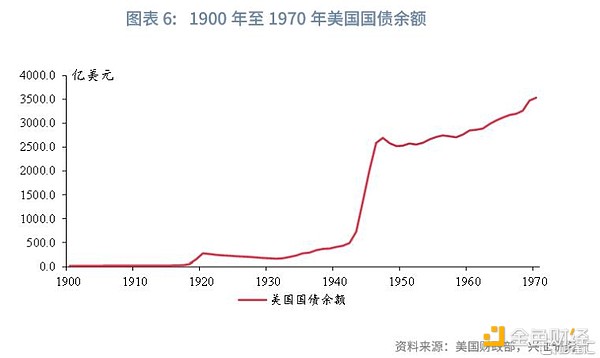

In 1833, Congress passed a compromise bill that stipulated that tariffs would be gradually reduced from 1834 to 1842 until all tariffs were reduced to 20%, which temporarily calmed the dispute between the interest groups of the North and the South over tariffs. However, with the change of government, the mutual struggle between the interest groups of the North and the South did not stop. In 1837, the United States experienced an economic crisis. In 1842, the "Black Tariff" was promulgated, and the US tariff level increased again. After the economic crisis, the Walker Tariff Act of 1846 was passed, and the US tariff level was reduced. It was not until 1861 that the American Civil War finally broke out. In 1861, the Morrill Tariff Act was enacted to raise military funds for wartime. Against the backdrop of high US government debt, the long-term rule of the Republican Party after the war allowed the United States to maintain a high tariff level for a long period of time.

1.1.2 From the Civil War to the Great Depression: Protecting Industries and Defending the Gold Standard

From 1863 to 1933, with the improvement of the tax system, the consideration of protecting industries and defending the gold standard became the main reasons for the United States to raise tariffs. From 1863 to 1913, as other taxes (such as consumption taxes) contributed more to fiscal revenue, the contribution of tariffs to U.S. fiscal revenue fell to about 50%. After the income tax was passed in 1913, the share of tariffs in U.S. fiscal revenue further declined, and from 1917 to 1933, the share of tariffs in U.S. fiscal revenue fell to below 20%. At the same time, we can also observe that since 1863, the average import tariff of all U.S. goods and the average import tariff of taxable goods have tended to diverge, which reflects that the United States has begun to impose tariffs on some industries in a targeted manner to protect the development of domestic industries in the United States.

In late 1892, the collapse of Baring Brothers triggered a run on the bank and a sharp monetary tightening, which led to the bankruptcy of many American railway companies. The US economy fell into recession, and US industrial production fell by 17% from its peak in May 1892 to its trough in February 1894. The unemployment rate jumped from less than 4% in 1892 to more than 12% in 1894. A large amount of gold flowed out of the United States, and the US "gold standard" monetary system was shaken (Irwin, 2017). McKinley was elected president in 1896, and in 1897 the McKinley administration signed the Dingley Tariff Act, which raised the average tariff level of taxable products in the United States from 40.2% in 1896 to 52.4% in 1899, the highest average tariff level for taxable goods since the American Civil War until the Great Depression of 1929. In his inaugural address, McKinley stressed the need to reduce the fiscal deficit and strengthen tariff protection for American industry. McKinley believed that higher tariffs would improve the fiscal deficit, reverse the trend of gold outflow, and help restore the country's prosperity and provide protection for industry.

From the perspective of the impact of the tariff law, fortunately, at roughly the same time that McKinley enacted the tariff law, the world's gold supply began to grow rapidly as supply from Australia, South Africa and Alaska increased. Under the "gold standard" monetary system, the easing of global monetary conditions promoted economic recovery and asset prices began to rise again. However, this somewhat coincidental timing led to the widespread belief at the time that McKinley's tariff law was the cause of the economic recovery (Irwin, 2017).

From 1895 to 1900, the export value of manufactured goods in the United States doubled, and the proportion of total exports increased from 26% to 35%. The export volume of manufactured goods increased by an astonishing 90%. The recovery of the global economic prosperity was one of the reasons for the surge in US exports. The increase in the export of manufactured goods strengthened the voice of some domestic producers in the United States with export demand, and questioned the necessity of high protective tariffs to restrict imports, and finally gave rise to the idea of reciprocity as a new approach to trade policy. In fact, Section 3 of the Dingley Tariff Act authorized the president to reduce tariffs on a certain list of specific goods for countries that made "reciprocal concessions" to US goods. However, in practice, most of the reciprocal treaties with foreign countries submitted by McKinley to Congress were not approved.

After entering the 20th century, the rising cost of living and the trust monopoly problem caused by the increase in industrial concentration at the end of the last century triggered a discussion on high tariffs in American society. Although economists were skeptical that tariffs would lead to rising inflation and increased industrial concentration, the power of the progressives within the Republican Party eventually prevailed, and in 1909 Congress passed the Payne-Aldrich Tariff Act, which significantly reduced tariff rates (Irwin, 2017).

1.1.3 The Great Depression: Protecting Industries and Defending the Gold Standard

The Great Depression in the United States that began in 1929 once again triggered a decline in U.S. net exports and an outflow of gold. In order to mitigate the impact of the Great Depression, the United States once again chose to raise tariffs, similar to the late 19th century. In 1930, the Hoover administration enacted the Smoot-Hawley Tariff Act, which further expanded the scope and level of tariffs on the basis of the existing high tariffs, causing the average tariff level of U.S. taxable products to rise from 40.1% in 1929 to 59.1% in 1932. The Hoover administration hoped to protect jobs and ease the economic crisis by raising tariffs.

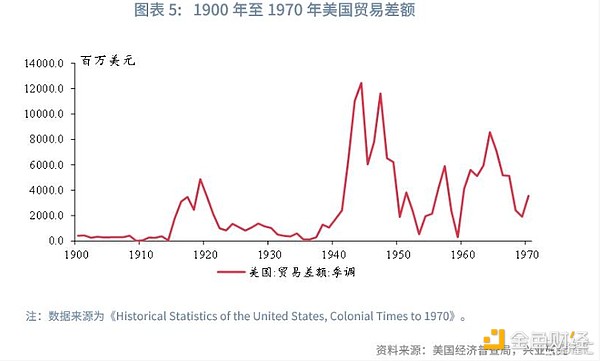

From the impact of the tariff law, after the United States implemented the Smoot-Hawley Tariff Act, major trading partners of the United States imposed tariffs on the United States. From 1929 to 1933, the amount of U.S. imports and exports both fell by more than 50%. However, the reduction in imported goods did not drive domestic production in the United States. The average annual GDP growth rate in the United States from 1929 to 1933 was -7.4%. At the same time, the unemployment rate in the United States rose sharply, and the economy experienced relatively severe deflation. In 1933, the unemployment rate in the United States was 24.9%, and the average annual CPI from 1929 to 1933 was -6.8% year-on-year.

In "Trade Wars in the 1930s - A Monetary System Narrative" published in April 2025, we mentioned that the fixed exchange rate under the gold standard was the crux of the economic depression that began in 1929, so abandoning the gold standard and devaluing the local currency became the first policy measure implemented by various countries. In September 1931, Britain announced its abandonment of the gold standard, and the pound depreciated by 30%. By 1935, the exchange rate of Britain had depreciated by 141% relative to the gold parity in 1929. Some countries that were closely linked to the pound exchange rate, such as Denmark, Sweden, and Norway, also abandoned the gold standard and devalued their currencies (Eichengreen & Sachs, 1985). This move effectively expanded the money supply, eased deflationary pressure, and improved export competitiveness, thereby promoting the economic recovery of countries that abandoned the gold standard. At the beginning of Britain's abandonment of the gold standard, the United States still adhered to the gold standard, and the economy fell into a deflation-recession spiral. The continued economic downturn caused the American people's growing dissatisfaction with the Hoover administration, and finally Hoover was defeated by Roosevelt in the presidential election in 1932.

After Roosevelt came to power, he immediately implemented the Emergency Banking Act and the Gold Reserve Act in March 1933 and January 1934, gradually abandoning the gold standard. Subsequently, in June 1934, the U.S. House of Representatives and the Senate passed the Reciprocal Agreements Act of 1934, which amended the Tariff Act of 1930. The main contents include: first, authorizing the negotiation of tariff agreements with foreign governments or institutions. Without the approval of the Senate, the President can sign trade agreements with foreign governments and modify the current tariffs and other restrictive trade measures, but the upper limit of the adjustment is 50%; second, follow the principle of unconditional most-favored-nation treatment of tariffs. After the passage of the Reciprocal Agreements Act, from 1934 to 1939, the United States signed a total of 22 trade agreements with other countries aimed at reducing their respective tariffs (Tan Tan, 2010), and the average tariff rate of U.S. taxable goods dropped from 59.1% in 1932 to 37.3% in 1939.

1.2 Free Trade Period

From 1934 to 1973, the United States was already the world's largest industrial country. During this period, the United States held high the banner of free trade and promoted American exports through reciprocal agreements. However, in the early 1970s, when the relative strength of American industry weakened and the international balance of payments was unbalanced, trade protectionism rose again.

Since the promulgation of the Reciprocal Trade Agreements Act in 1934, the United States has promoted trade by reducing tariffs through bilateral and multilateral free trade systems, and maintained a low tariff level for a long period of time. The average tariff level of taxable products in the United States dropped from 46.7% in 1934 to 10.0% in 1970.

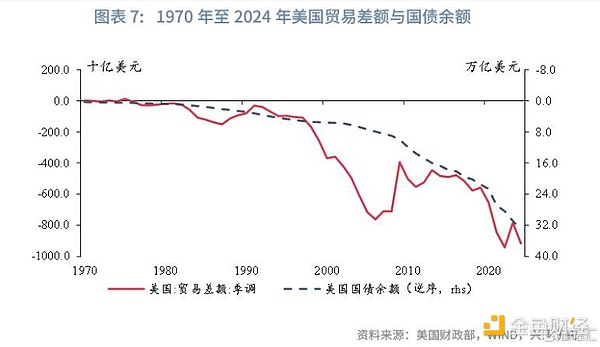

In order to cope with domestic economic stagflation, rapid growth of fiscal deficits, deterioration of international balance of payments and the dollar crisis, the Nixon administration launched the "New Economic Plan" in 1971, which mainly included wage and price controls, suspension of gold and dollar convertibility, and an additional 10% tariff on all taxable imported goods. Among them, wage and price controls were aimed at controlling inflation, the suspension of gold-dollar exchange was to ease the dollar crisis caused by the continuous outflow of gold under the Bretton Woods system, and the additional 10% tariff on all taxable imported goods was to ease the deterioration of the balance of payments. Nixon used the 10% additional tariff as a negotiating tool, trying to cancel the additional tariff in exchange for the appreciation of other countries' currencies.

From the impact of the plan, the "New Economic Plan" played a certain role in stabilizing the economy and controlling inflation in the short term. The US GDP growth rate rose from 5.2% in 1970 to 10.2% in 1972, and the CPI year-on-year growth rate fell from 5.7% in 1970 to 3.2% in 1972. Then stagflation returned. In 1974, the US GDP growth rate fell back to 8.8%, and the CPI year-on-year growth rate rose again to 11.0%.

At the end of 1971, the United States and its trading partners reached the Smithsonian Agreement. The US dollar depreciated against gold, other foreign currencies appreciated against the US dollar, and the United States abolished the 10% tariff. However, the exchange rate established in the Smithsonian Agreement did not last long. In 1973, the US dollar was in crisis again and the Bretton Woods system collapsed.

1.3 The period of non-tariff barriers under the cover of free trade

Since 1974, the United States has protected its economy by setting up non-tariff barriers under the condition of low overall tariff levels. From 1975 to 2018, the average tariff level of US taxable products remained below 6%. Since 2019, the average tariff level of US taxable products has risen, from 5.6% in 2018 to 7.4% in 2023.

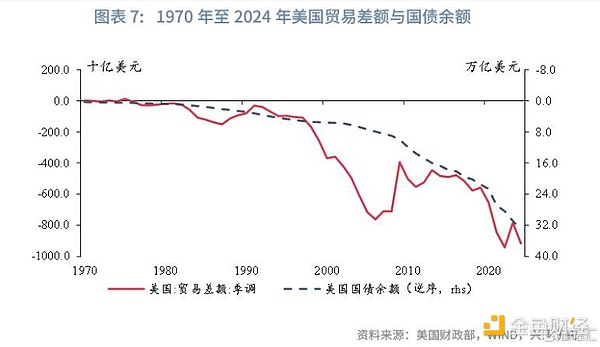

During this period, the US trade deficit has expanded rapidly. In 2024, the US trade deficit was US$9.2 trillion, accounting for 3.1% of the US GDP, while in 1974, the US trade deficit was only US$4.29 billion, accounting for 0.1% of the US GDP at that time.

II. Revelation

It is not difficult to find that trade protectionism rises in the United States every few decades. It took 69 years from the Tariff of 1828 to the Dingley Tariff of 1897; about 33 years to the Smoot-Hawley Tariff; 41 years later came the Nixon shock; and 47 years later Trump began to abuse tariff policies.

Protecting domestic industries, improving international balance of payments, and reducing fiscal deficits are the unchanging motivations for trade protectionism. In the early days of American industrialization, the motivation to protect domestic industries was even stronger; and as the US economy matured and the US dollar became the global standard currency, the imbalance between international balance of payments and fiscal balance of payments gradually became an inducement for trade protection.

However, the high tariff policy that goes against the tide of history is doomed to be unsustainable, and with the deepening of globalization, the duration of high tariffs is getting shorter and shorter. Five years after the Tariff of 1833, the US Congress passed a compromise bill to reduce tariffs; four years after the Smoot-Hawley Tariff, the US House of Representatives and the Senate passed the Reciprocal Trade Agreements Act; the deepening of globalization after World War II made it even more difficult for high tariffs to survive, and Nixon's additional tariff policy lasted less than a year. Only the Dingley Tariff Act coincided with the growth of global gold production and lasted for a long time.

The direct reasons for the end of high tariffs are more complicated. The dissatisfaction of the American people with high prices, the opposition of domestic interest groups, and the countermeasures of trading partners may all lead to a turning point in trade protection. Regardless of the direct incentives for reducing tariffs, the turning point of tariff policy is usually accompanied by fundamental changes in the monetary system, such as a sharp depreciation of the US dollar or a significant increase in gold production. This means that there may be a trade-off between the monetary system and tariffs, and the excessive imbalance of the balance of payments must eventually be corrected.

Alex

Alex