Author: Sleepy.txt

This autumn has been particularly cold for the tech industry.

On October 28th, Amazon announced plans to cut up to 30,000 corporate jobs, nearly 10% of its total workforce, its largest layoff since the end of 2022. CEO Andy Garcetti stated that the company will replace some positions with AI.

The US human resources software company Paycom also laid off more than 500 employees earlier this month; their positions will be replaced by "AI and automation".

A month ago, Just Eat Takeaway, Europe's largest food delivery company, announced 450 layoffs, citing "automation and AI" as the reason. Two weeks prior, freelance platform Fiverr laid off 30% of its workforce, with the CEO stating the company's goal was to become an "AI-native company." In addition, Meta, Google, Microsoft, and Intel have also tightened their workforce. These layoffs weren't for assembly line workers, but for specialized positions requiring high levels of education, years of experience, and rigorous interviews, including software engineers, data analysts, and product managers. For a long time, they believed skills were a moat, education was insurance, and hard work would eventually pay off. According to TrueUp, a tech industry layoff tracking website, hundreds of thousands of tech professionals have lost their jobs this year. The impact of AI doesn't begin with low-skilled jobs; it first shakes up those intellectually demanding jobs considered the safest and most professionally protected. Even more brutally, this replacement process isn't gradual. AI won't replace 10% of jobs first, then 20%, then 30%; instead, at a certain tipping point, entire departments will be eliminated. The essence of labor is exchanging time for money. Time is inherently finite, and the biggest risk of this system lies in its continuity. Once labor is forced to stop, whether due to unemployment, illness, or old age, income will immediately cease. This is the common predicament that all those who earn income by selling their time will ultimately face. Stalling Wages, Wildly Rising Assets

In April 2024, Scott Galloway, a professor at NYU's Stern School of Business, published an article titled "War on the Young." He stated that from 1974 to 2024, the median real wage in the United States increased by 40%, while the S&P 500 index rose by 4,000% during the same period. A full hundredfold difference.

This means that if you had $10,000 in 1974 and invested it in the S&P 500, it would become $400,000 by 2024.

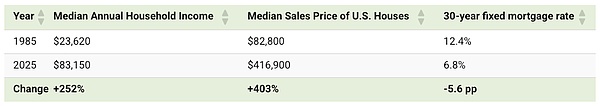

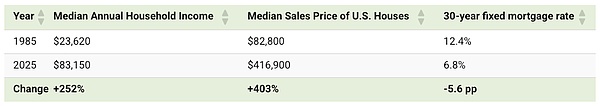

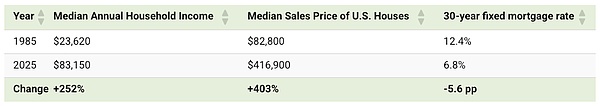

But if you started working in 1974 and saved money little by little from your salary, by 2024 you could only buy 40% more than you did back then. Research from the Washington-based think tank, the Center for Equitable Growth, further confirms this trend. Since the beginning of the 21st century, wage growth has lagged behind almost all other sources of income. Capital gains, dividends, and interest—income that doesn't require you to clock in every day—have grown far faster than wages. This gap has already permeated everyone's daily life. In 1985, the median home price in the United States was $82,800, while the median annual household income was $23,600, meaning home prices were approximately 3.5 times income. Forty years later, home prices had risen to $416,900, while income had only increased to $83,150, widening the ratio of home prices to income to five times.

Comparison of Median Income, Home Prices, and Mortgage Rates in the US in 1985 and 2025|Source: Visual Capitalist

In the San Francisco Bay Area, home prices have risen far faster than the national average, while income growth for tech workers has been relatively limited. An engineer who joined Google in 2015, earning over $100,000 a year, had his eye on a two-bedroom apartment in South Silicon Valley that cost around $2 million. He thought that if he worked a few more years and saved enough for a down payment, he could afford it. Five years later, his salary increased, but home prices rose even faster. That apartment became $3 million; and by 2025, it has approached $4 million.

Wages have barely doubled, but housing prices have nearly doubled and a half. Ten years later, he's even further from owning that house. From the beginning of 2021 to mid-2025, US consumer prices rose by 22.7%, and average hourly wages increased by 21.8%. On paper, your wages are rising, but when converted to the cost of living, you can buy less. This is precisely the dilemma for many wage earners; for them, wealth growth almost never keeps pace with the rising cost of living. Wages are rising, but so are rent, electricity bills, and childcare expenses. Data from the World Inequality Lab shows that in the US, the top 10% of workers earn five times more than the bottom 50%. But at the wealth level, this gap is magnified a hundredfold. The wage gap is merely superficial; what truly determines fate is the gap in capital. For most people, wealth accumulation depends on the investment of time; but for those who already possess capital, time itself is the engine of wealth. As assets appreciate and appreciate further, no matter how fast workers chase after them, it's difficult to surpass that ever-rising curve. The middle class trapped in an illusion. This structural gap is particularly pronounced in the tech industry. That was once the industry workers dreamed of. High salaries, stock options, and a seemingly eternal promise—that as long as you're smart enough and hardworking enough, you can achieve financial freedom through your own labor. This belief has sustained an entire generation of knowledge-based middle-class individuals and forms the core of the Silicon Valley narrative. However, the wave of layoffs in 2025 tore a crack in this narrative. A report released by the Boston Consulting Group in February of this year, targeting high-income groups in North America, showed that they surveyed several thousand people in Canada with annual incomes between $75,000 and $200,000—presumably upper-middle class or even wealthy. The results revealed that only 20% felt financially secure, nearly a third felt their situation had become more unstable in the past year, and about 40% feared being laid off. This anxiety is becoming increasingly prevalent among the American middle class. According to a survey by US media, nearly half of those earning over $100,000 annually report living paycheck to paycheck. One Amazon engineer in Seattle earns $180,000 a year, seemingly a glamorous job, but he has to pay $4,000 a month for mortgage payments, $2,000 for childcare, $1,000 for car loans and insurance, and $500 for student loans. His after-tax income is approximately $11,000, leaving him with less than $1,000 in savings. "I feel like I'm trapped on a treadmill, afraid to stop," he said in an interview. "I'm afraid to change jobs; the new position might pay less. I'm afraid to get sick because taking leave will affect my performance." This anxiety illustrates that what people are truly uneasy about isn't the amount of income; a high salary doesn't equal security. True financial security comes from passive income, that is, income that doesn't depend on continuous labor. As long as life is still tied to working hours, even the highest salary is only temporary stability. Besides wages, stock options were once seen as the key to wealth for working people. It made countless engineers, product managers, and designers believe that they were not only employees of the company but also "co-owners." Every overtime shift, every night of product launch, seemed to contribute to future wealth accumulation. But reality is backfiring on this narrative. A product manager who had worked at Meta for three years discovered after being laid off that he still had half of his stock options that hadn't vested, worth approximately $150,000 based on the stock price at the time. However, due to his departure, those options were all forfeited. "I always thought they were my assets," he said, "but they were just a tool the company used to retain you. Once you leave, they're nothing." Stock options, seemingly an allocation of capital, are essentially a deferred payment for labor. They postpone risk and bring forward hope, allowing employees to extend their working hours in an illusion. More and more tech professionals are beginning to realize that security doesn't come from the level of salary, but from the proportion of capital in one's personal income structure. They began searching for paths to transition from "laborers" to "capital owners." The first path is entrepreneurship. It's about shifting from selling your own time to buying other people's time, from employee to boss. This is the most direct, but also the most difficult, path. According to the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics, approximately 20% of startups fail in their first year, less than half survive within five years, and less than 30% survive for ten years. And of those 30%, only a very small minority achieve true financial freedom. The second path is delayed gratification. Believers in the FIRE (Financial Independence, Retire Early) movement believe that with sufficient self-discipline, saving a large portion of their income and investing in assets that generate stable returns, they can escape the constraints of work sooner. It sounds like a rational choice—restraint, saving, and letting compound interest work for you. But in cities like San Francisco and New York, saving half your annual salary amidst high rents and the cost of living almost means giving up socializing, travel, and consumption. Even more difficult is that this delayed gratification requires maintaining a high income, staying employed, avoiding illness, and escaping unforeseen circumstances. If any of these variables go wrong, the plan will be disrupted. Besides these two paths, many young people are starting to explore new possibilities. They are no longer satisfied with simply keeping money in bank accounts to earn interest, nor do they rely solely on company-provided pensions; they are actively learning about asset allocation and letting their money work for them. According to research reports, Millennials and Generation Z are among the first to widely use automated investment tools early in their careers. They prefer to manage their accounts personally and their investments are more diversified, ranging from stocks and bonds to index funds and even crypto assets. This shift is driven by anxiety. As high salaries no longer equate to security, and as the rise of AI makes "stability" increasingly difficult to achieve, investing—a game once reserved for the wealthy and professional institutions—is being relearned and redefined by today's young people. The most mainstream choice remains investing in traditional financial markets, such as stocks and index funds. For young people who cannot afford to buy a house, Real Estate Investment Trusts (REITs) offer another compromise. According to Nareit data, the total market capitalization of US REITs exceeded $1.4 trillion in 2025. By purchasing REITs, people can indirectly hold a portion of commercial real estate with relatively little capital, sharing in the appreciation of the real estate market, which can also be seen as hedging against ever-rising rents and housing prices. However, for many young people, this is still too slow. They grew up in the internet age, are naturally close to new technologies, and are more risk-averse. In their pursuit of financial freedom, they are beginning to turn their attention to a more radical area—cryptocurrencies. A report released by A16Z in October 2025 mentioned that since the advent of ChatGPT, a large number of talents have continued to flow from traditional finance and technology companies into the crypto world. As artificial intelligence arrives at the center of the new world, the crypto field continues to attract a group of people chasing uncertain opportunities. For many tech workers, the crypto world offers a seemingly faster path. In traditional companies, they receive salaries and stock options, which can only be cashed out when the company goes public or is acquired. In crypto projects, however, compensation is often distributed in the form of tokens, which can be traded on the secondary market as soon as the project launches, offering far greater liquidity than traditional equity. For those tired of waiting, this means a more direct incentive. But crypto remains a highly volatile gamble. Price swings occur far more frequently than with any traditional asset, with daily fluctuations of 20-30 percent becoming commonplace. This investment frenzy precisely illustrates how hopeless the traditional path can be. Starting a business is too difficult, FIRE (Financial Income, Investment, and Retirement) is too slow, and the returns on traditional investments can't keep up with rising asset prices. This leads people to prefer constantly betting on a risky new field. These factors act like a mirror, reflecting not greed, but anxiety. The Cost of the New Order All of this ultimately converges on two curves. In the first three quarters of 2025, the S&P 500 rose 17%, and the Nasdaq rose 22%. Those who held stocks saw their wealth grow. At the same time, real wages were declining, and the unemployment rate was rising. The two curves, one upward and one downward, are widening in distance. This is not accidental. When the growth rate of labor income fails to keep pace with the cost of living, and when AI begins to threaten the stability of highly skilled jobs, people will naturally seek other sources of income—investment, speculation, gambling, and arbitrage. This anxiety is most pronounced in emerging industries. The question is, where will this shift lead society as a whole? If more and more people begin to rely on investment, what will happen to those without capital? How can a recent college graduate, without savings or family support, acquire their first pot of gold? If the only way is through gradual accumulation via wages, and wage growth cannot keep up with asset price increases, they will never catch up with those already ahead, leading to further social stratification. Another question is, to what extent will the total amount of human work decrease as AI continues to replace labor? In the future, AI and robots may replace most human jobs. This is not a short-lived economic cycle; in this transformation, the meaning of labor, the source of income, and even the value of "effort" are being redefined. Historically, humanity has faced similar moments. In the early stages of the Industrial Revolution, machines replaced manual labor, leading to widespread unemployment among textile workers and plunging society into chaos and anger. But ultimately, industrialization did not destroy labor; rather, it reshaped it. New jobs were created, new industries emerged, and overall productivity and living standards were elevated to a new level. The question is, will the AI revolution follow a similar path? No one knows the answer. The transformation of the Industrial Revolution took more than a century, accompanied by countless social upheavals, strikes, and redistributions. The speed of the AI revolution far surpasses that era. In less than three years since ChatGPT's release, it has already transformed the job market. As algorithms can write code, generate content, handle customer service, and formulate strategies, the so-called "professional skills" are being redefined. Perhaps the end of labor is not the end of work itself, but rather the redistribution of its meaning. AI will not cause complete unemployment, but it is rewriting the essence of "work" and reshaping the source of "security." In the next decade, this new distribution order will determine the form of the economy and how individuals find their place and dignity within it.

Anais

Anais