Source: Quantum

When you think of AI’s contribution to science, you probably think of AlphaFold, Google DeepMind’s protein-folding program whose creators won a Nobel Prize last year.

Now, OpenAI says it’s getting into science, too — building a protein engineering model.

The company says it has developed a language model that can come up with proteins that can turn ordinary cells into stem cells — and it has handily beaten humans.

The study is OpenAI’s first model to focus on biological data, and the first time the company has publicly claimed that its model can provide unexpected scientific results. As such, it’s a step toward determining whether AI can make real discoveries, which some see as a major test toward “general artificial intelligence.”

Last week, OpenAI CEO Sam Altman said he was “confident” his company knew how to build general artificial intelligence, adding that “superintelligent tools could dramatically accelerate scientific discovery and innovation, far beyond what we humans can do ourselves.”

The protein engineering project began a year ago when Retro Biosciences, a San Francisco-based longevity research company, approached OpenAI to discuss a partnership.

This collaboration is no accident. OpenAI CEO Sam Altman reportedly personally provided Retro with $180 million (about 1.318 billion yuan) in funding.

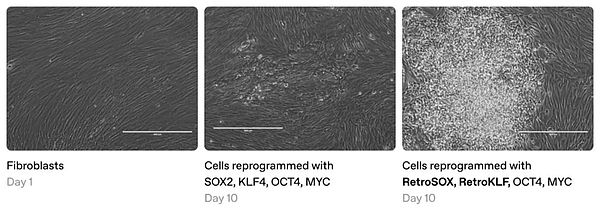

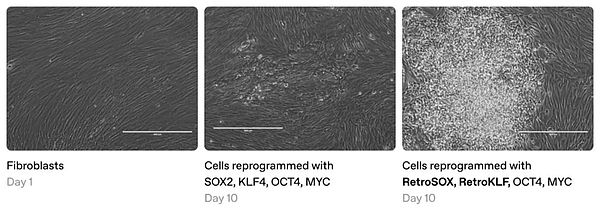

(Image source: OpenAI)

Retro's goal is to extend the normal human lifespan by 10 years. To do this, the company studied the so-called Yamanaka factors (or induced pluripotent stem cells). This is a group of proteins that, when added to human skin cells, turn them into seemingly youthful stem cells, a type of cell that can give rise to any other tissue in the body.

Researchers at Retro and other well-funded companies like Altos Labs see the phenomenon as a possible starting point for rejuvenating animals, making human organs or providing replacement cells.

But this cellular “reprogramming” isn’t very efficient. It takes weeks, and less than 1% of the cells treated in a lab dish complete the regenerative journey.

OpenAI’s new model, called GPT-4b micro, is trained to suggest ways to redesign protein factors to enhance their function. According to OpenAI, the researchers used the model’s suggestions to increase the efficiency of two Yamanaka factors by more than 50 times — at least according to some preliminary measurements.

“Overall, the proteins seem to work better than what scientists could produce themselves,” said John Holman, a researcher at OpenAI.

Holman and Aaron Jack of OpenAI and Rico Meni of Retro were the lead developers of the model.

Outside scientists can’t tell if the results are real until they’re published, which the companies say they plan to do. The model also hasn’t been made more widely available yet — it’s still a custom demo, not a formal product launch.

“This project is about showing that we’re serious about contributing to science,” Jack says. “But whether these capabilities will come out as a separate model or baked into our main inference model — that’s yet to be determined.”

The model works differently from Google’s AlphaFold, which predicts the shape of proteins. OpenAI says that because Yamanaka factors are unusually soft and unstructured proteins, they required a different approach, one that its large language models were well suited to.

The model was trained on samples of protein sequences from many species, as well as information about which proteins tend to interact with each other. While the data is large, it’s only a small fraction of what OpenAI’s flagship chatbot was trained on, so GPT-4b is an example of a “small language model” using a centralized dataset.

Once Retro scientists had the model, they tried to guide it to come up with possible redesigns of Yamanaka’s protein. The prompting strategy used was similar to the “few-shot” approach, where users ask the chatbot a question by providing a series of examples with answers, and then provide an example for the bot to respond to.

While genetic engineers have ways to direct molecular evolution in the lab, they can usually only test a limited number of possibilities. And even proteins of average length can be altered in nearly infinite ways (because they’re made of hundreds of amino acids, each with 20 possible variants).

Yet OpenAI’s model often gave suggestions for changing just one-third of the amino acids in a protein.

“We immediately put this model into the lab and got real results,” says Joe Bates-Lacroix, CEO of Retro. He also said the model’s concept was very good and that it was an improvement over the original Yamanaka factor in a significant number of cases.

Vadim Gladyshev, an expert on aging at Harvard University and an adviser to Retro, said better ways of making stem cells were needed. “For us, this would be very useful. [Skin cells] are easy to reprogram, but other cells are not,” he said. “And to reprogram in a new species — usually it’s very different and you get nothing.”

Exactly how GPT-4b came up with its guesses is unclear — AI models often are. “It’s like AlphaGo beat the best human player at Go, but it took a long time to figure out why,” Bates-Lacroix said. "We're still trying to figure out what it does, and we think we've only scratched the surface of how we're applying it."

OpenAI CEO Sam Altman (Photo credit: TechCrunch, CC BY 2.0, via Wikimedia Commons)

OpenAI said no money was exchanged in the partnership. But because the research could benefit Retro, whose largest investor is Altman, the news could raise more questions about the OpenAI CEO's sideline.

Last year, the Wall Street Journal said Altman's extensive investments in private tech startups amounted to an "opaque investment empire" and were "generating more and more potential conflicts" because some of those companies also did business with OpenAI.

For Retro, simply being associated with Altman, OpenAI and the AGI race raises its profile and strengthens its ability to recruit employees and raise money. Bates-Lacroix did not respond to questions about whether the early-stage company is currently in the fundraising phase.

OpenAI said Altman was not directly involved in the work and the company never made decisions based on Altman's other investments.

Weatherly

Weatherly