By Byron Gilliam, Blockworks

There was a pleasant time when Federal Reserve chairmen had the freedom to lecture politicians about their irresponsible spending habits.

In 1990, for example, Alan Greenspan told Congress that he would lower interest rates, but only if Congress cut the deficit.

In 1985, Paul Volcker even put a number on it, telling Congress that the Fed’s “stable” monetary policy depended on Congress cutting about $50 billion from the federal budget deficit.

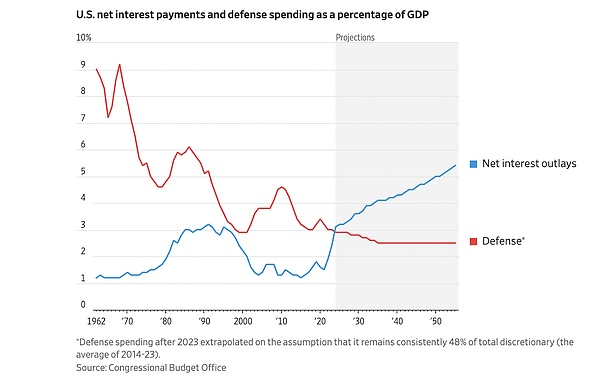

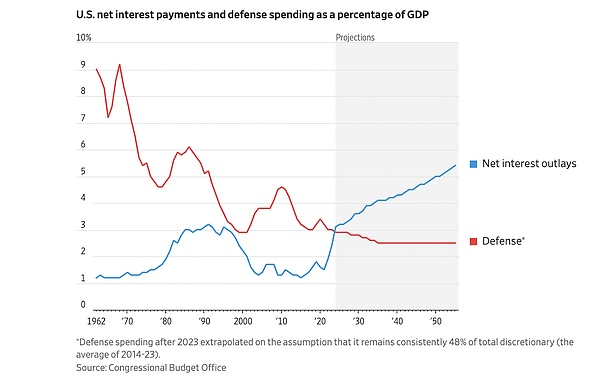

(Ah, that’s $500 billion in federal debt, not even in the era of rounding errors.) In both cases, the Fed chairmen were implicitly threatening Congress and the White House with recession risks: You have a great economy right now, and it would be a shame if something went wrong. Now, however, the situation is reversed, with President Trump lecturing the Fed about interest rates. In recent weeks, Trump has commented that the federal funds rate is "at least 3 percentage points higher," insisted there is "no inflation," and mocked Federal Reserve Chairman Jerome Powell as "Too Late Powell." This, too, is a form of pressure: You have good central bank independence... Trump also lobbied for lower interest rates during his first term. Like nearly all modern American presidents, he wants the Fed to stimulate the economy. This time, however, it’s about much more than that: Trump wants the Fed to finance the deficit. The Trump-Powell showdown is ostensibly about the current level of interest rates (the Federal Open Market Committee (FOMC) left them unchanged today, which presumably displeased the president). But what the president has been threatening is “fiscal dominance”—a state in which monetary policy is subordinated to the government’s spending needs. “Our interest rates should be three percentage points lower than they are now, saving the country $1 trillion a year,” the president recently wrote on Truth Social in his signature casual capitalization. By repeatedly making such statements, Mr. Trump made history as the first American president to explicitly call for fiscal dominance. But he was by no means the first to acknowledge the possibility. When Mr. Volcker and Mr. Greenspan threatened Congress with rate hikes, they brought to the surface the usually hidden connection between monetary and fiscal policy. It worked for them: Both Fed chairmen successfully used the threat of recession to get Congress to address deficit spending, a hopeful precedent. But that strategy seems unlikely to work this time. Chairman Powell has frequently warned of the risks of growing deficits, even explaining that higher deficits could mean higher long-term interest rates. But it's hard to imagine him issuing the explicit threats of Volcker and Greenspan—perhaps because he knows he's in a significantly weaker bargaining position. In the 1980s, the most feared consequence of raising interest rates was a recession, a risk the Fed was willing to take to persuade Congress to change its extravagant spending habits. Back then, lawmakers faced a ballooning defense budget and a stagnant economy, both of which seemed manageable. At just 35% of GDP, the federal debt also looked manageable.

Now,

<Chart: The rapidly rising blue line represents the proportion of federal debt interest payments to GDP, which far exceeds defense spending>

“I guess it was the banks’ problem, not my problem,” Trump later wrote about being unable to repay his debts. “What the hell do I care? I even told one bank, ‘I told you you shouldn’t have loaned me money, I told you that damn deal ain’t gonna work.’ ”

Now, as president, when Trump tells Powell that interest rates should be lower, what he’s really saying is that the national debt is the Fed’s problem, not his.

He’s not wrong. “When interest payments on the debt rise and fiscal surpluses become politically unfeasible,” writes David Beckworth, a former U.S. Treasury economist, “something has to give. That sacrifice is more debt, more money creation, or both.” Yes, the Fed could resort to the Volcker/Greenspan maneuver and threaten Congress with higher interest rates. But Powell probably knows that if he does, it will only exacerbate a problem that the Fed may eventually need to solve—and hasten the point at which it will be forced to do so. “If debt levels get too high and keep growing,” Beckworth explained, “the Fed’s job becomes to accommodate—either by holding down interest rates or monetizing the debt.” That, he warned, is the Fed’s real existential threat, not Trump: “When a central bank is forced to accommodate fiscal demands, it loses its economic independence.” Beckworth remains hopeful that it might not come to that. Perhaps not. We’ve seen how unpopular inflation is, so if there’s another bout of it, voters might force lawmakers to address the deficit. But he despairs that focusing on Trump’s demands for lower interest rates is a red herring: “What we are witnessing is less about Trump himself than about the growing and unavoidable fiscal demands being placed on the Fed.” Trump was the first to make these demands explicitly, presumably because he knows that the US government’s current fiscal policy is unsustainable. But everyone knows that, even the government itself. The only question now is: who will deal with it?

Joy

Joy