Tenth in a series of studies on stablecoins and crypto assets

Since the second half of 2023, with the rapid expansion of market size and the rapid expansion of usage scenarios, stablecoins have become an important bridge connecting the cryptocurrency market and the traditional financial economic system.

Based on the analysis of the operating model and potential risks of stablecoins, this article analyzes the stablecoin regulatory practices in major countries and regions such as the European Union, the United States, Japan, Singapore, Hong Kong, China, and the United Arab Emirates, According to the regulatory framework of "how to define stablecoins - who will issue them - what to regulate - how to redeem them - how to prevent money laundering", this article analyzes the theoretical issues and current development trends behind stablecoin regulation.

Overall, global regulatory practices reflect five major trends in stablecoin regulation:

1) Currently, stablecoins are used as payment tools and mainly support the development of legal currency stablecoins;

2) Stablecoin issuers are subject to licensing supervision and are required to establish local entities;

3) Operational supervision of issuers is moving closer to the regulatory framework of commercial banks and payment institutions;

4) The focus of reserve management redemption supervision is to stabilize asset value and protect user redemption rights;

leaf="">5) Adapt to the regulatory requirements of financial institutions for anti-money laundering and anti-terrorist financing and strictly implement the rules.

Article source: Zhu Taihui, Research on the framework, theory and trend of global stablecoin supervision, "Financial Supervision Research 2025 Issue 3. This article is a simplified version, please download the detailed journal version from CNKI.

"Stablecoin" is an encrypted digital value expression that meets the following conditions: it is issued and traded based on blockchain and distributed ledgers, expressed in the form of accounting units or storage of economic value, maintains a relatively stable value with a single asset or a group or basket of reference assets, can be accepted by the public and used as a transaction medium for payment of goods or services, repayment of debts, and investment, and is transferred, stored or bought and sold electronically. As a type of cryptocurrency, stablecoins can be divided into legal currency-backed stablecoins (such as USDC, USDT), cryptocurrency-backed stablecoins (such as DAI), physical-backed stablecoins such as gold, silver and commodities (such as PAXG), and algorithm-backed stablecoins according to the types of collateral assets behind them. Among them, legal currency-backed stablecoins occupy the majority of the entire stablecoin market, and the market value of US dollar stablecoins alone accounts for about 95% of the stablecoin market.

Among cryptocurrencies, stablecoins, especially fiat-backed stablecoins, have the stability and credibility of legal tender, and also have the advantages of decentralization, globalization, anonymity, transparency, high efficiency and low cost brought by blockchain to cryptocurrencies. Therefore, they have become a bridge between the cryptocurrency system and the traditional financial system and real economic activities, and have therefore become the focus of recent cryptocurrency research.

Based on the analysis of the operating model and potential risks of stablecoins, this paper analyzes the regulatory practices of stablecoins in major countries and regions such as the European Union, the United States, Japan, Singapore, Hong Kong, China, and the United Arab Emirates. According to the regulatory framework of "how to define stablecoins - who will issue them - what to regulate - how to redeem them - how to prevent money laundering", this paper analyzes the theoretical issues and current development trends behind the regulation of stablecoins.

1. Stablecoin operation model and potential risks

Stablecoins have multiple types, providing different trade-offs in decentralization, stability and risk to meet different demand preferences in the financial ecosystem. Different types of stablecoins adopt different operation models, and there are differences in issuing institutions, redemption mechanisms, stabilization mechanisms, etc. If we do not consider the challenges brought by stablecoins at the macro level, such as sovereign currency substitution, cross-border capital control, and monetary policy regulation, from the perspective of operation model and functional mechanism, stablecoins mainly have three potential risks:

First, market risk, liquidity risk and credit risk. This type of risk is closely related to the selection and management of stablecoin reserve assets, especially the extent to which they can be liquidated at or close to current market prices. The ability of stablecoins to sell reserve assets in large quantities at current market prices depends on the maturity, quality, liquidity and concentration of stablecoin reserve assets.

Second, operational risk, network risk and data loss risk. This type of risk is closely related to potential vulnerabilities in the governance, operation and design of the stablecoin infrastructure, including its ledger and the way it verifies user ownership and token transfers. The degree of vulnerability of stablecoins in this regard is affected by the effectiveness of the governance and control of the stablecoin operating model.

Third, there is the vulnerability risk of global stablecoin applications and components. This type of risk is related to the applications and components that users use to store private keys and trade stablecoins. Since these are operational matters of wallets or exchanges, this type of risk will have different specific manifestations under different stablecoin operating models.

In addition, since the various activities and functions of stablecoins are interrelated, the above risks will also transform into each other.

Second, the regulatory definition of the use of stablecoins

The regulation of the definition and use of stablecoins mainly focuses on two issues. One is whether to issue stablecoins backed by domestic currencies, or whether to issue stablecoins backed by foreign currencies. The theoretical issues behind this are: Is the stablecoin backed by legal tender a global currency and payment tool? What impact will it have on monetary policy? Will the stablecoin backed by foreign currency affect the monetary sovereignty of the country?

Another question is whether stablecoins backed by crypto assets and algorithmic stablecoins are supported in addition to stablecoins backed by legal tender? The theoretical issues behind these are: What functions of currency are stablecoins backed by legal tender performing? Can stablecoins backed by crypto assets and algorithmic stablecoins also effectively perform these functions?

The definition and regulatory policies on the use of stablecoins in major countries and regions such as the European Union, the United States, Japan, Singapore, the United Arab Emirates, and Hong Kong, China, reflect the following major trends: (1) Currently, countries mainly support stablecoins backed by fiat currency (payment stablecoins), and at the same time regulate the use of fiat currency stablecoins with reference to digital payment regulation; (2) Most of them support the simultaneous issuance of local currency stablecoins and foreign currency stablecoins within the country, but in order to maintain the stability of sovereign currencies, they set restrictions on the scope of use of foreign currency-backed stablecoins; (3) Uncollateralized algorithmic stablecoins have too great a volatility risk and have not yet been recognized by regulatory authorities in various countries. It should be noted that, although in a narrow sense, legal tender-backed stablecoins and electronic payment tools have great similarities (this is also the reason why the United States, Singapore, the United Arab Emirates and other countries regulate stablecoins based on payment regulations), there are still huge differences between the two: from the perspective of business model, stablecoin transactions are decentralized and programmable, while electronic payment tools are centralized and not programmable; from the perspective of functional attributes, legal tender-backed stablecoins are not only payment tools, but also investment tools, and are the basis of DeFi businesses such as decentralized lending, while electronic payment tools are only payment tools. These differences mean that the regulatory framework of electronic payment institutions cannot be fully applied to the access supervision and operation supervision of stablecoin issuers.

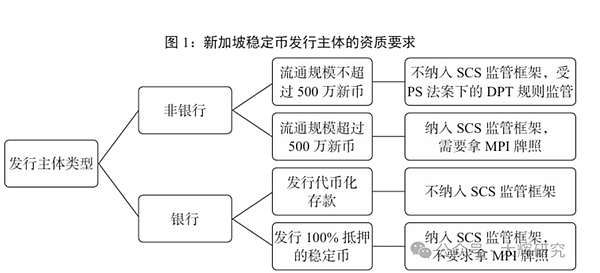

III. Access supervision of stablecoin issuers

After clarifying the definition, type and use requirements of stablecoins, the regulatory issue of stablecoin issuance follows: whether stablecoin issuance requires a license and what kind of access conditions should be established. The theoretical issue behind this is how big the difference is between the business scope (deposits, loans and foreign exchange) of stablecoin issuers, trading service institutions, payment institutions and banking institutions, and whether credit creation has been carried out.

The access supervision policies of major countries and regions such as the European Union, the United States, Japan, Singapore, the United Arab Emirates, and Hong Kong, China on stablecoin issuers show that it is a global trend to implement licensed access and supervision on stablecoin issuers. Regulatory authorities of various countries (regions) also require issuers to establish stablecoin issuance and operation entities in their own countries/regions as a means to implement supervision and impose penalties.

In terms of license types, banking institutions themselves can serve as issuers and traders of legal tender-backed stablecoins, while payment service providers/money transfer service providers are optional license types, indicating that regulatory authorities in various countries currently recognize the monetary payment and settlement functions of legal tender stablecoins.

In addition, most regulatory authorities in various countries currently require that stablecoin issuers cannot pay interest on stablecoins and cannot directly provide lending services, so they cannot create multiple credits like banks.

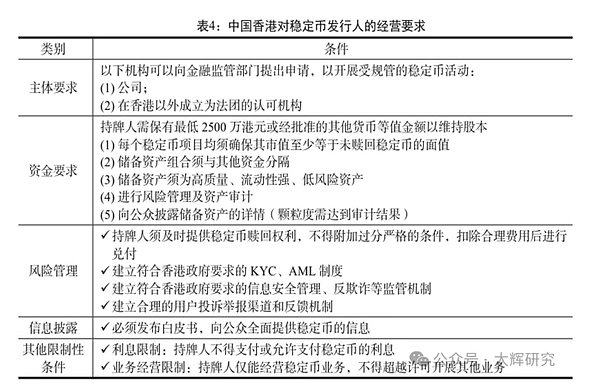

IV. Operational supervision of stablecoin issuers

From the perspective of the regulatory process, after clarifying the nature and positioning of the product and the entry requirements of the issuing institution, it is necessary to formulate the operating and management requirements of the issuing institution. The theoretical issue behind this is whether the operational supervision of the stablecoin issuers should follow the "same activities, same risks, same supervision" principle proposed by the FSB, whether it should follow the existing regulatory framework for banking institutions or payment institutions, and what targeted adjustments need to be made in terms of capital, business scope, operating requirements, risk management, etc.?

The regulatory policies on the operation and management of stablecoin issuers in major countries and regions such as the European Union, Singapore, the United Arab Emirates, and Hong Kong, China show that although there are certain differences in the specific measures of various countries in implementing the "same activities, same risks, same supervision" principle, they generally refer to the operational and regulatory framework of banking institutions and payment institutions, and most of them clarify the minimum capital requirements, business operation requirements, business scope, risk management mechanism, corporate governance requirements, etc. of stablecoin issuers.

At the same time, the EU and other countries also refer to the idea of "systemically important financial institutions" supervision, and evaluate whether stablecoins belong to "important crypto assets" based on the number of stablecoin customers, market value, transaction scale, etc., and impose additional risks and own capital requirements on important crypto asset issuers. Among them, the EU and Hong Kong have also formulated recovery and disposal plans similar to those in systemic banking supervision.

In addition, all countries require stablecoin issuers to set up entities locally and employ a certain number of local managers as a means to implement regulatory requirements.

V. Management and supervision of stablecoin reserves

For stablecoins backed by fiat currencies, it is the core key to ensure that users can redeem fiat currencies at any time, so it is necessary to focus on the supervision of the reserves of stablecoin issuers. The theoretical issue behind this is that if countries refer to banks or payment institutions for access and operation supervision of stablecoin issuers, should the management of stablecoin reserves refer to the capital and liquidity supervision of banks and the customer reserve requirements of payment institutions?

The regulatory policies of the European Union, the United States, Singapore and other countries on the reserves of stablecoin issuers show that around the main line of stabilizing the value of reserve assets and preventing user runs, all countries have put forward more or less requirements for the third-party isolation custody of stablecoin reserve funds, the scope and proportion of investment assets, the customer redemption mechanism and time limit, and the priority order of repayment when the issuer goes bankrupt, which has already formed a trend. Compared with the regulatory framework of existing financial institutions, these countries' requirements for the custody, investment and redemption of stablecoin reserves are, on the whole, a combination of bank liquidity supervision requirements and payment institutions' reserve fund management requirements.

VI. Stablecoins Anti-Money Laundering and Anti-Terrorist Financing Supervision

Stablecoins are issued and traded based on blockchains, and have the characteristics of decentralization, globalization, anonymity, and convertibility (convertible into legal currency). The chain bridge technology strengthens the interconnection of different blockchains, making it easier for money launderers to hide their identities and sources of funds. The irrevocability of transactions on the blockchain will also hinder the pursuit and recovery of money laundering and terrorist financing, resulting in more complicated forms of money laundering and terrorist financing in stablecoins and cryptocurrencies. Therefore, how to prevent the potential money laundering and terrorist financing risks of stablecoins has become the focus of attention of regulatory authorities in various countries. Under the existing anti-money laundering and anti-terrorist financing regulatory framework for financial institutions, the theoretical issue that needs to be considered behind this is what is the focus of anti-money laundering and anti-terrorist financing in stablecoin transactions and what is the grip?

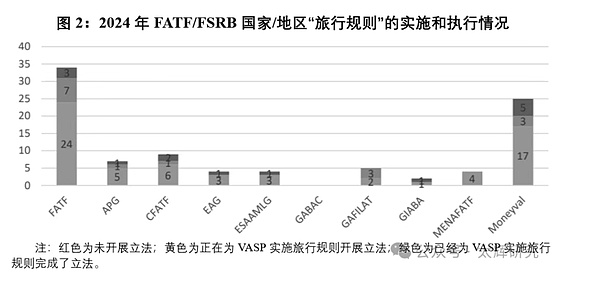

In June 2019, the Global Financial Action Task Force (FATF) updated the "FATF Recommendations on International Standards for Combating Money Laundering, Terrorist Financing and Proliferation Financing" (hereinafter referred to as the "FATF Recommendations") issued in 2012, and included virtual asset activities and virtual asset service providers (VASPs) in the international standards for anti-money laundering and counter-terrorist financing by adding "interpretations" to "Recommendation 15 (New Technologies)".

The regulatory policies on anti-money laundering and anti-terrorist financing of stablecoins/cryptocurrency assets in major countries and regions such as the European Union, the United States, Singapore, and Hong Kong, China show that most countries have transplanted the anti-money laundering and anti-terrorist financing requirements for payment institutions (money service providers) and banking institutions to the field of stablecoins/cryptocurrency assets, and compliance with FATF anti-money laundering standards has gradually become a trend.

At the same time, based on the decentralization, globalization, anonymity, convertibility, and irrevocability of stablecoin/cryptocurrency transactions, FATF and the above-mentioned countries have further put forward some more targeted requirements, such as reducing the transaction amount applicable to the "travel rule". The EU requires that crypto asset service providers must provide information about remitters and beneficiaries when transferring crypto assets, otherwise any amount of cryptocurrency will not be allowed to be transferred between accounts of crypto asset service providers (CASPs), which is significantly higher than the 1,000 euro/dollar starting point proposed by FATF for the travel rule.

VII. Research Enlightenment

Through the sorting and analysis of the current stablecoin regulatory policies of some major countries and regions, the following policy enlightenment can be obtained:

First, for financial innovation supported by emerging technologies, the formulation of financial regulatory policies can follow the idea of "principles first, gradual improvement". In the early stage, it is necessary to follow up the business development dynamics in a timely manner. After roughly understanding the operating model and potential risks of the innovative business, first formulate a principled regulatory plan, and then revise the policy continuously according to the innovative development and risk situation. However, in the long run, the operating model and risk characteristics of stablecoins, cryptocurrencies and decentralized finance (Defi) are very different from the existing financial system. It may not be appropriate to follow the principle of "same business, same risk, same regulation" and copy the regulatory framework rules of the existing financial system. In the future, it may be necessary to build a financial regulatory model and rules that are more compatible with the decentralized financial ecosystem.

Second, for financial innovation supported by new technologies, the implementation of financial regulatory policies needs to follow the principle of "technological neutrality and innovative supervision". Financial innovations supported by new technologies need to use new technologies to change the concepts, models and tools of supervision and promote the digital transformation of supervision. For example, in stablecoins and cryptocurrency products and businesses based on blockchain and distributed ledgers, the information contained in the blockchain is verified by decentralized economic consensus and guaranteed by economic incentives; while the reliability of data in current supervision is guaranteed by the legal system, regulatory authorities and regulatory penalties. In view of this, financial regulatory authorities need to apply blockchain and distributed ledger technology to financial supervision in the future and actively implement "embedded supervision".

Third, for financial innovation supported by new technologies, the implementation of financial regulatory policies needs to follow the principle of "benign interaction, knowing each other". For financial innovation driven by cutting-edge technologies, there is very little that financial regulatory authorities can really do at the beginning. This requires regulatory authorities to adhere to the concept of open supervision, through equal and open communication with the regulated departments, to deeply grasp the mechanism and nature of innovation, and at the same time let market players stand at a higher level to enhance compliance concepts and risk awareness. For example, with the continuous formulation and implementation of regulatory policies, the risk awareness of stablecoin issuers is also constantly improving. In August 2024, Circle, the issuer of the stablecoin USDC, proposed that stablecoins need to go beyond the adequate capital reserve requirements of the existing Basel banking regulatory framework to mitigate the risks unique to stablecoins, other fiat currency equivalent tokens and their issuers. The "Token Capital Adequacy Framework" (TCAF) constructed on this basis adopts a dynamic risk-sensitive model, starting from stress test reserves and stakeholder opinions, while considering technical risks such as blockchain network performance and network security, and mitigating the externalities of negative risks through incentive accountability.

Hui Xin

Hui Xin

Hui Xin

Hui Xin Kikyo

Kikyo Jasper

Jasper YouQuan

YouQuan Brian

Brian Hui Xin

Hui Xin Joy

Joy Jasper

Jasper Catherine

Catherine Jasper

Jasper