Author: Bai Ding, Geekweb3

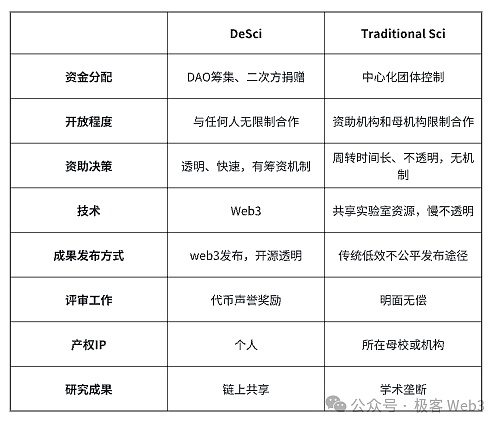

Recently, due to Vitalik and CZ nominating DeSci, this concept has become a hot word and has sparked widespread discussion. From the literal meaning, DeSci mainly refers to "decentralized science". Aiming at the centralization problem inherent in the traditional academic research process, DeSci attempts to change the publishing and dissemination model of academic activities in a decentralized way, making the scientific research field more open and fair.

There are deep-rooted structural problems in the traditional academic research and dissemination system. A few publishers such as Elsevier and Springer have basically monopolized the dissemination channels of high-quality papers by controlling top journals, which has produced serious negative effects. In addition, due to various reasons such as the inadequacy of the traditional academic evaluation system, many scientific research works have become "paper carvings, papers are supreme" in recent years, squeezing out the innovation and practicality of scientific research; on the other hand, the unequal distribution of resources has aggravated the "marginalization" of academics in developing countries, leading to a systematic imbalance in global scientific research.

In this context, we urgently need to rethink: Should academic papers really be paid for? What is the key to the academic community's problems? Combined with the recent hot words such as Sci-Hub, we might as well conduct a preliminary discussion on DeSci and look forward to the possibility of openness and progress brought to the academic community by combining Web3 with the field of scientific research.

Publishers' monopoly on academic journals

Journals are an important carrier of academic research results and a medium for promoting scientific progress. However, the biggest problem in today's traditional academic community is precisely related to journals. From Nature, The Lancet to Cell, the influence of top journals goes far beyond publication and dissemination, and has become the core of the scientific research evaluation system. The number of results published in journals of different levels is an important credential for researchers in the distribution of academic discourse power, which makes the operation model of academic journals inevitably mixed with fame and fortune, and has commercial characteristics, which is the essence of the current traditional academic system.

From submission to publication, papers have to go through a complicated process of editing, peer review, and final publication. There are many operational places in it. For example, the paper review is mainly evaluated by experts in the field. Relatively authoritative scholars in the field will be invited to participate, but these experts often cannot get financial rewards through reviewing. As a result, this "free" step has become one of the gimmicks for publishers to increase pricing. Using the authority of reviewers as a selling point, they in turn charge high subscription fees to people who read journals.

People are not completely ignorant of this operation model, but based on the high degree of market monopoly of academic publishers, they have to accept the reality. A few publishing giants, such as Elsevier, Springer Nature and Wiley, control almost 70% of the world's scientific journals. This monopoly position gives publishers strong bargaining power. They regard academic journals as high-end commodities and set prices based on high impact factors and prestige effects rather than actual operating costs.

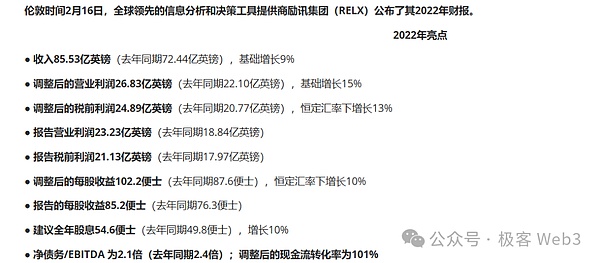

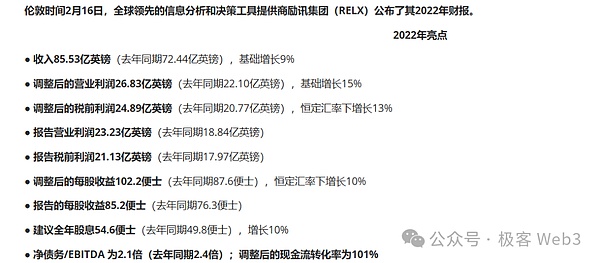

Institutions and individuals have to pay high fees when subscribing to journals, and even have to be forced to buy hundreds of journals in a package to obtain certain journal resources. This unscrupulous bundling sales model is called "BigDeal". Elsevier's parent company, RELX Group, had a profit margin of 30%-40% in the technology field in 2022, exceeding technology giants such as Apple and Google.

These strange phenomena all indicate a problem: the academic world is now highly market-oriented and monopolistic market-oriented. Monopoly will bring negative externalities, and a minority of groups will reap the monopoly benefits. The ultimate beneficiary of the academic market is undoubtedly the capital represented by publishers, while the negative externalities are borne by researchers and readers in the academic world.

Impact Factor and Demand Price Elasticity

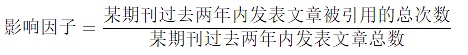

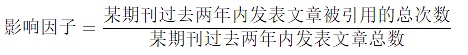

In traditional academia, the impact factor plays a pivotal role, and the impact factor of a journal is one of the important indicators used to measure the influence of the journal. The calculation method is as follows:

For example, the impact factor of a journal in 2024 is 5.0, which means that each article published in the journal in 2022 and 2023 was cited an average of 5 times in 2024, which is a relatively objective level. Journals with high impact factors have great fame and fortune for the authors of the published papers, have high academic influence, and are generally called "top journals".

It is precisely because of "having goods in hand" that publishers can earn monopoly profits. Take Elsevier as an example. Its parent company RELX Group's revenue in 2022 exceeded US$8 billion, of which STM (science, technology and medicine) publishing business accounted for the largest proportion, with a profit margin of 30%-40%. In contrast, the profit margins of global technology giants such as Apple and Google are only about 20%-25%, which shows the huge profit margin of academic publishing. In contrast, the cost of university subscription journals has increased by 5%-7% each year, even far higher than the monetary inflation rate.

From RELX Group's 2022 Financial Report

Such a huge profit margin makes publishers reluctant to give up this "academic cake". In addition, the academic community has a rigid demand for high-impact journals. Publishers use their monopoly position to maintain a high-price strategy, and at the same time transform researchers' intellectual property rights into their own commercial assets through copyright agreements. This business model has transformed academic journals from a bridge for knowledge dissemination into a tool of capital, hindering the openness and fairness of scientific research.

In 2019, the University of California system suspended its subscription service for two years because it could not afford Elsevier's high fees. Even in the world's leading universities, there is this phenomenon of "scientific researchers cannot afford to read papers", not to mention the scientific research difficulties faced by small and medium-sized institutions.

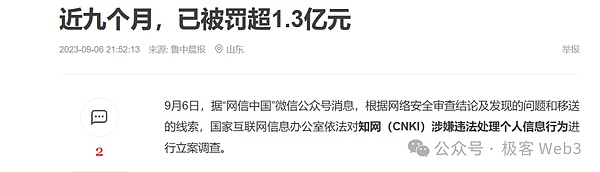

CNKI also has similar problems. In 2016, the library of Wuhan University of Technology issued an announcement that between 2010 and 2016, the price of CNKI increased by 132.86%. The school believed that the price increase was too large and unbearable, so it decided to suspend the use of CNKI database services. In 2021, Nanjing University announced that it would suspend the use of CNKI on the grounds that the subscription fee of CNKI continued to rise, bringing huge financial pressure to the school. In April 2022, the Documentation and Information Center of the Chinese Academy of Sciences issued a notice that it decided to suspend the use of CNKI database because the renewal fee of CNKI has reached the level of tens of millions.

So far, CNKI has been fined a total of more than 130 million yuan for monopoly and violations.This can also roughly estimate the order of magnitude of its reliance on academic resources to obtain huge profits.

From "Luzhong Morning News"

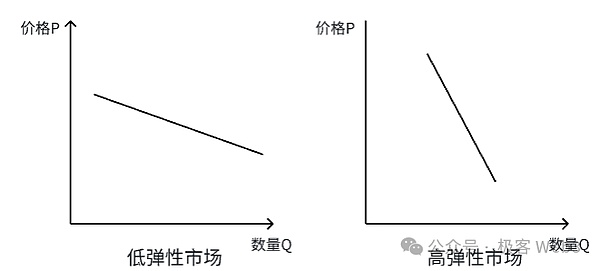

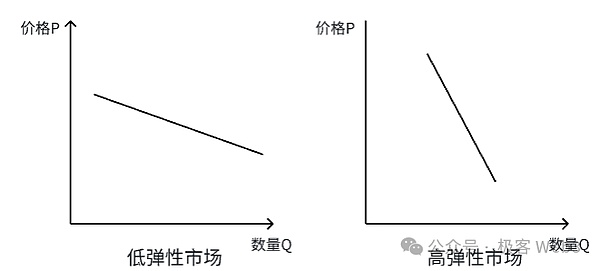

In fact, in the final analysis, the root cause of the monopoly of academic resources lies in the fact that the demand for technical resources by scientific researchers is too rigid. The sensitivity of market demand to price changes is called "demand price elasticity" in economics. The more necessary the goods, the lower the elasticity, such as food, medicine, water and electricity bills, etc.; on the contrary, the more non-necessary the goods, the higher the elasticity, such as luxury goods, fast-moving consumer goods, etc. The comparison of the demand curves of the two is shown in the figure below.

Compared with the general e-book market, the academic publishing market is small in scale but highly sticky, so the price elasticity of demand is extremely low. Since scientific research institutions and scholars rely heavily on specific journals, publishers are almost not restricted by market competition in pricing. Once the supplier obtains a monopoly position in this "rigid demand market", since there are almost no substitutes, the monopoly price can be raised as high as possible, and the subscription fee and submission fee will always be high.

Such an academic publishing system has also invisibly exacerbated the inequality in the distribution of global academic resources. Developing countries and small and medium-sized institutions are often unable to afford the high subscription fees for journals, which restricts their academic development. Even small and medium-sized institutions in developed countries face the same problem. Well-known universities and top institutions are usually able to sign "Big Deal" agreements to obtain comprehensive academic resources, while small and medium-sized institutions can only purchase a small number of journals, or even rely entirely on public resources. And the more this is the case, the less likely small countries and small institutions are to attract more talent and funds, and fall into a vicious cycle.

Academic papers are public goods

From an economic perspective, knowledge itself is non-exclusive and non-competitive, and naturally belongs to public goods. And scientific research mostly relies on public funding support, especially basic scientific research, which is usually funded by government grants or support from public welfare organizations. This means that the production process of scientific knowledge itself is a cause jointly funded by the whole society. Therefore, research results should be a public resource shared by all mankind, rather than being monopolized by a few publishers through various channel advantages. Publishers commercialize scientific results, not only setting up high-price barriers to access, but also restricting authors from freely sharing in other scenarios through copyright agreements. This closed model obviously violates the concept of public goods, and further, it is contrary to the spirit of modern scientific research collaboration. Free access to academic papers is even more significant in narrowing the resource gap between scientific research subjects with different economic strengths. At present, many universities and research institutions in developing countries cannot subscribe to expensive academic journals due to budget constraints, making it difficult for researchers to follow up on international cutting-edge research, and their research capabilities are further marginalized. If academic papers can be made free and open, it will greatly improve the research conditions in these countries and allow more researchers to participate equally in global scientific exchanges.

More importantly, the free and timely access of papers by more researchers, educators and the public will greatly accelerate the dissemination and innovation of knowledge, which is of great significance to society in avoiding direct and major losses. For example, after Hurricane Katrina, the timely update of meteorological research results significantly reduced casualties in the subsequent hurricanes; the flood control design concept adopted by the "Delta Project" in the southwest of the Netherlands was derived from academic research, which avoided the recurrence of disasters similar to the 1953 flood; and the timely update of scientific research results in the medical field can save countless lives.

Sci-Hub: An attempt to break through publishing barriers

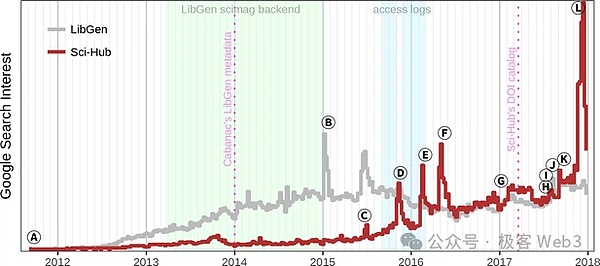

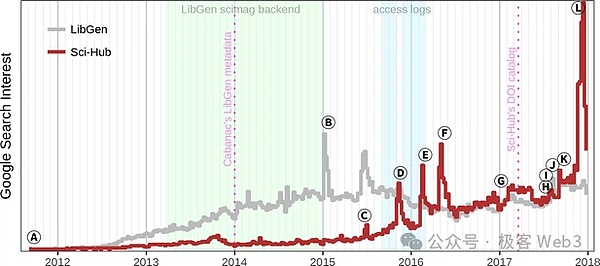

Against the background of high academic journal subscription fees and huge knowledge barriers in traditional industries, the emergence of Sci-Hub in 2011 can be said to be a revolution. As the world's largest "shadow library", Sci-Hub not only challenges the monopoly of publishing giants, but also redefines the way knowledge is disseminated. Some even say that the significance of Sci-Hub is comparable to Prometheus stealing fire to bring light to mankind, or liberating knowledge from the monopoly of the church during the Renaissance. Since its establishment, Sci-Hub has become more and more well-known, and it has become well-known on the Internet since 2018.

The data comparison in the above figure shows that people's metaphor for Sci-hub does not seem to be excessive. Even non-professional scientific researchers, I believe that everyone who has received a master's degree or above can feel the inestimable value of a free paper knowledge base. What's more, Sci-Hub does not belong to the country, does not belong to the government, has no grants and subsidies, and is only created and operated by private individuals, which is undoubtedly even more valuable.

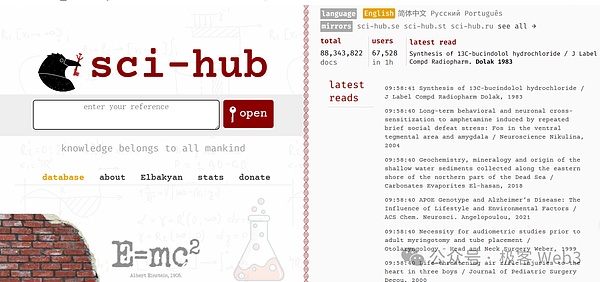

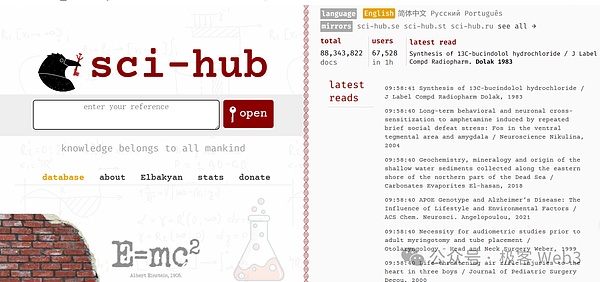

Sci-Hub is a free academic paper acquisition platform founded in 2011 by Alexandra Elbakyan, a Kazakh (born in the former Soviet Union). Elbakyan's original intention was to break the monopoly of academic publishers on knowledge dissemination and allow everyone to have equal access to academic resources. She once said: "Scientific knowledge should be the common wealth of all mankind, not a private resource seized by a few people." So far, Sci-Hub has collected nearly 90 million academic papers, covering the content of most mainstream journals in the world.

As a free platform, Sci-Hub obtains paper resources in the following ways:

The first is to use the academic resources subscribed by universities and research institutions to obtain papers with the help of authorized access. Universities and research institutions usually subscribe to the databases of large publishers such as Elsevier, Springer, Wiley, etc. Sci-Hub uses the accounts provided by academic users to access these resources, and then uses scripts to automatically download papers in batches within the scope of authorization and save them to its own server.

This practice of snatching cheese from mainstream publishers is of course unacceptable to the latter. In 2016, a legal document from the Southern District Court of New York in the United States showed that Sci-Hub used the legitimate accounts of some academic institutions to download Elsevier's papers in batches without authorization, which directly led to Elsevier filing a copyright lawsuit.

The second is that when Sci-Hub has a certain reputation, it has been supported by many academic users and has received spontaneous support from these people. They may be scholars, students, or staff of research institutions, who will take the initiative to provide access rights to Sci-Hub or directly upload academic resources. This behavior has allowed Sci-Hub to collect a large number of paper texts in a short period of time. Alexandra Elbakyan (founder of Sci-Hub) once mentioned in an interview that many academic users took the initiative to contact Sci-Hub and expressed their willingness to contribute accounts or downloaded documents to support knowledge sharing.

The third type is more special. Sci-Hub may use some means to exploit or cause the leakage of account information of some universities or institutions to obtain access to subscribed resources.

There are reports that some account leaks may come from phishing emails targeting university libraries or publisher database users. Sci-Hub uses these leaked accounts to download papers in batches; some university or institutional users use simple or repeated passwords (such as "123456" or account names), making the accounts easy to crack. Sci-Hub or its supporters use automated scripts to conduct password probing attacks, find accounts with weak passwords, and then log in in batches. In addition, operations such as not changing passwords in time and not logging out after leaving the job will give Sci-Hub "opportunities to take advantage of."

At this point, we can certainly see that Sci-Hub's known ways of obtaining academic resources are actually very controversial, but they are still within the scope of discussion. We are more concerned about a question: Has Sci-Hub used drastic illegal acts to obtain papers?

Although Sci-Hub's founder Alexandra Elbakyan has repeatedly denied using hacking methods to directly attack publishers' databases, she emphasized that Sci-Hub's acquisition of resources mainly relies on voluntary account sharing and technical exploitation of vulnerabilities. However, according to reports from some publishers and security experts, some account leaks may indeed involve technical means of hacker attacks, such as using automated tools to crack weak passwords, or attacking the internal networks of universities or research institutions to steal user login information.

Although Sci-Hub's acquisition method is controversial and even regarded as infringement and illegal by publishers, in the eyes of many scholars and supporters, this behavior is the most powerful evidence of Sci-Hub's fight against traditional academic monopoly, an "inevitable revolution" in knowledge sharing, and a necessary counterattack against the monopoly and high pricing model of the existing publishing system.

From this we can see that the attitude of ordinary researchers towards Sci-Hub can be said to be completely opposite to that of publishers. Why? As a non-profit platform, Sci-Hub has opened up access to academic knowledge for hundreds of millions of researchers, students and the general public around the world. In many developing countries, Sci-Hub is even the only choice for researchers to obtain the latest research results. According to statistics, Sci-Hub has been downloaded more than 650 million times, a considerable number of which came from developing countries. For example, in 2017 alone, Iran and India contributed 25 million and 15 million downloads respectively.

Under the shadow of knowledge monopoly, the emergence of Sci-Hub has benefited almost all scientific researchers, especially enabling scientific knowledge to reach those who are excluded due to economic, geographical and other reasons, injecting new vitality into the fair dissemination of knowledge. However, although Sci-Hub is of great significance in breaking down knowledge barriers, it touches the interests of others after all, and its operation faces challenges in different aspects.

The first is the issue of compliance. The existence of Sci-Hub poses a direct threat to the business model of publishing giants, facing the latter's continuous lawsuits and blockades. Publishers such as Elsevier and Springer have filed lawsuits against Sci-Hub many times, accusing it of copyright infringement. Court decisions usually require Sci-Hub to stop operating, and the domain name has been blocked many times.

For example, in 2017, a US court ruled in favor of Elsevier, and several domain names of Sci-Hub were forced to close. Since its establishment, Sci-Hub has been blocked more than 10 times. For example, in countries such as India and Russia, publishers have tried to block access to Sci-Hub through legal means, but users can often continue to use it through VPNs and mirror sites.

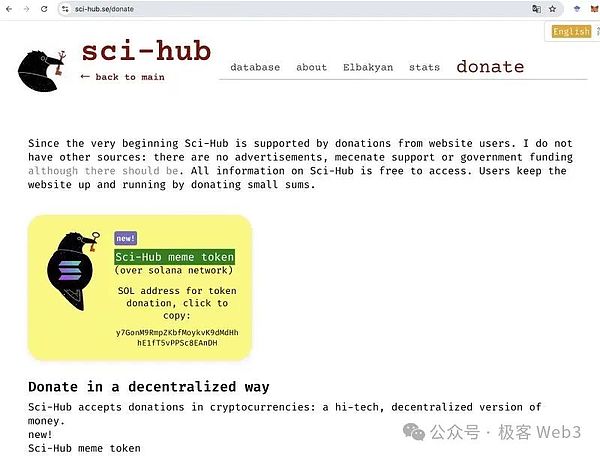

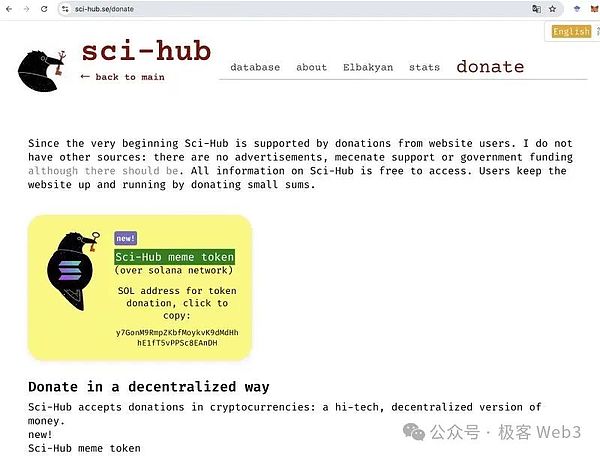

The second is the common problem of public goods - the source of funds. Sci-Hub's operation depends entirely on user donations and support from university accounts.There is nostablesource of revenue, which makes the sustainability of the platform very challenging. A report in 2020 showed that Sci-Hub's main source of income was Bitcoin donations, with an annual donation amount of about $120,000, but this is far from enough to cover the platform's server and operating costs.

In 2024, some netizens spontaneously promoted memecoin, which has the same name as Sci-Hub. After memecoin became popular, they donated 20% of the total tokens to Sci-Hub, which is about $5 million based on the current market value, which largely solved Sci-Hub's dilemma.

To summarize, despite Sci-Hub’s great achievements in knowledge sharing, its model is not without limitations. First, Sci-Hub’s legal status is unstable, and the long-term survival of the platform is seriously threatened. Second, Sci-Hub solves the problem of knowledge acquisition, but does not fundamentally change the business model or power structure of academic publishing.

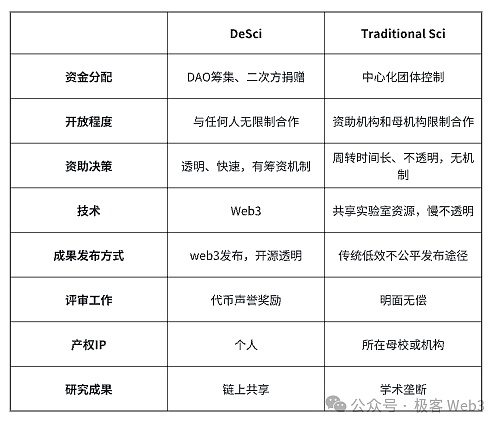

Perhaps, blockchain technology can provide a better solution to breaking the academic monopoly. The concept of decentralized science (DeSci) can use blockchain to achieve transparent sharing of academic papers, decentralized management of intellectual property rights, and fair distribution of funds. Compared with Sci-Hub’s passive acquisition model, DeSci provides a more legalized and systematic way of sharing knowledge.

DeSci: The future path to solve academic monopoly

As the monopoly and high cost of traditional academic publishing models become increasingly prominent, decentralized science (DeSci) is providing new hope for solving these challenges. The core vision of DeSci is to use blockchain technology and decentralized concepts to create a new scientific research ecosystem that does not rely on a few publishers and funding agencies. In this ecosystem, researchers can directly obtain funding, their results can be publicly accessed, and intellectual property rights can be transparently managed to ensure that all contributors can share the benefits fairly.

Blockchain has the advantage of underlying logic in solving money-related problems. DeSci can record the publication, citation and review process of papers on the chain to ensure transparency and credibility, and significantly reduce costs or increase scholars' income through technologies such as smart contracts to help them overcome financial difficulties.

Token, as the core product of blockchain, can help researchers obtain more diversified sources of income. In the vision of the DeSci platform, papers can be published for free, and Token rewards can be directly provided to researchers based on data such as reading and citation. In this regard, Arweave has tried to combine open access with blockchain to ensure permanent preservation and fair access to documents. In this way, for researchers, DeSci has reduced costs and increased revenue, which can be described as "increasing revenue and reducing expenditure."

In addition,new organizational relationships like DAO can bring more transparency to the DeSci research system.In DeSci, research funding can flow directly to specific research projects, and achieve de-intermediation as much as possible. Through the DAO decision-making mechanism based on community voting, funders can choose to support projects of interest and monitor the use of funds in real time.

In addition, for knowledge items such as papers and research data, property rights clarification is a core issue that is difficult to bypass. In the traditional academic publishing model, the ownership of intellectual property rights and the distribution of benefits are often controversial. For example, most academic journals require researchers to transfer the copyright of their papers to publishers, and it is difficult for researchers themselves to benefit from the subsequent dissemination of academic results. In the open access (OA) model mentioned above, although papers can be made public for free, the high article processing fees still transfer the economic burden to researchers.

And NFT is naturally suitable for solving similar copyright/property rights clarification issues. DeSci uses IP-NFT (Intellectual Property Non-Fungible Token) technology to digitize the property rights of scientific research results and record them on the blockchain, making the ownership of property rights transparent and tamper-proof, thus completing patenting. Researchers can directly own and control intellectual property rights without transferring copyright to publishers. In addition, the distribution of revenue is also automatically executed by smart contracts. Every time a paper is cited or scientific research data is used, the revenue will be distributed to the relevant contributors in real time.

This model not only solves the problems of copyright transfer and unfair revenue in the traditional publishing system, but also encourages the sharing and cooperation of scientific research data. At present, some projects have made attempts in this direction. For example, on the decentralized biomedical research platform Molecule, the research team can convert new drug patents into IP-NFTs, and benefit funders and team members through a transparent distribution mechanism. This mechanism brings new fairness and efficiency to intellectual property management and is a key link for DeSci to promote open sharing of science.

In general, compared to Sci-Hub, which uses some non-mainstream means to open up a shaky academic oasis under the logic of traditional Internet, DeSci is more like trying to innovate or even "revolutionize" from the underlying logic, providing a completely new system and platform for academic resources.

JinseFinance

JinseFinance