Author: Degg_GlobalMacroFin

1. US debt will reach a peak of 6 trillion in June this year

Recently, there is a very popular saying: US debt will reach a peak of 6 trillion in June this year, and there is a huge risk of rolling refinancing. This is a trap that Biden deliberately left for the Trump administration.

There is also a popular view that after the debt limit problem is alleviated, a large number of US debt issuances will trigger a "liquidity crisis" or significantly push up US debt interest rates. The author originally planned to write a long article to systematically answer the long-term and short-term risks of US debt, but because there are too many friends who have asked recently, I will simply write a reply here.

2. Ask the most fundamental question first: Is the monthly maturity of US debt an important indicator?

Answer: It is not important. What is important is the issuance volume (not the maturity volume) of US Treasury bonds with a maturity of more than 1 year (i.e. notes and bonds).

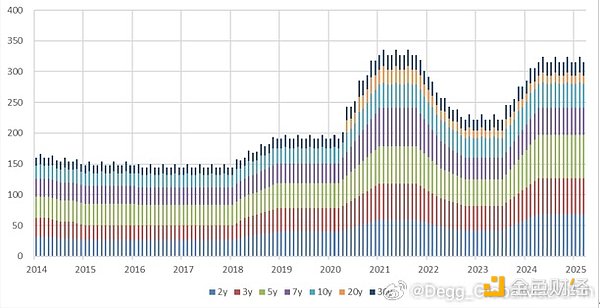

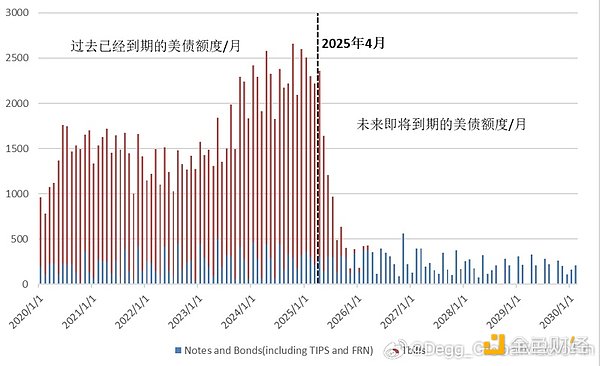

Explanation: The issuance mechanism of US Treasury bonds is not "immediately issue 100 yuan of 5-year US Treasury bonds to continue the maturity of 100 yuan of 5-year US Treasury bonds", but can be summarized in one sentence: "Long-term bonds are issued as planned, and short-term bonds are used for emergencies". Since the duration of long-term bonds (notes and bonds, US Treasury bonds with a maturity of more than 1 year) is much higher than that of short-term bonds (Tbills), in order to ensure stable market demand, the Ministry of Finance will plan the issuance volume of long-term bonds for the next quarter in advance at the quarterly refinancing meetings in January, April, July and November each year, and basically will not make temporary changes. If there is a temporary increase in the deficit (such as the epidemic), the financing gap fluctuation will be smoothed by issuing more Tbills. This is why we see that the issuance of long-term bonds usually remains stable over a period of time, unlike the deficit and the issuance of Tbills, which jump up and down (Figure 1).

Why can Tbills be issued/reduced at will? Because the term of Tbills is very short and the demand is very elastic. In extreme cases, the Ministry of Finance can issue cash management bonds (CMBs) with a maturity of one day, which can almost be regarded as a substitute for reserves and overnight repurchases. As long as its interest rate is a few bps higher than SOFR, EFFR, IORB, ONRRP rate, etc., 6 trillion MMF + 3.4 trillion bank reserve funds will flow into the market. Therefore, the interest rate of Tbills is mainly affected by the current and short-term policy interest rate expectations of the Federal Reserve, and is not very affected by supply changes. An intuitive way to understand it is that the large-scale issuance of 50-yuan banknotes will not cause its price to fall to 49.5 yuan.

Because Tbills has such flexibility, if the maturity of US Treasury bonds at a certain stage is particularly large, and the issuance of long-term bonds planned in advance is not very high, the Ministry of Finance can issue a large number of Tbills to fill the financing gap. This has little impact on the operation of major asset classes and financial markets, unless you are a money market fund PM who specifically deducts those bps.

Of course, this is a short-term emergency measure to ensure that the money that should be raised is obtained without disrupting the operation of the market and without significantly increasing the financing cost. If the fiscal deficit continues to increase and the number of maturing US bonds continues to grow over a period of time, this approach will lead to an increase in the proportion of Tbills, making the Ministry of Finance's future annual interest expenditure increasingly dependent on the future policy interest rate path of the Federal Reserve, and unable to lock in future interest rates several years in advance like issuing long-term US bonds. This is why when the Ministry of Finance decides on the issuance plan of long-term bonds, in addition to the high or low interest rates, it always has to balance the market demand for duration (suppressing the Ministry of Finance's willingness to issue long-term bonds) vs. the interest rate risk borne by the Ministry of Finance (pushing up the Ministry of Finance's willingness to issue long-term bonds). Once the issuance of long-term bonds is significantly increased, it is possible to significantly push up the term premium and interest rate level of US bonds. One example is that in October 2023, the 10-year US bond interest rate quickly exceeded 5% due to the continuous issuance of long-term bonds by the Ministry of Finance.

Therefore, we say that it is better to focus on the issuance of U.S. Treasuries than on the maturity of U.S. Treasuries. Instead of focusing on the issuance of U.S. Treasuries, it is better to focus on the issuance of long-term bonds - it depends on the fiscal deficit and the maturity of U.S. Treasuries, and more importantly, it depends on the balance of various factors by the Ministry of Finance. In the final analysis, U.S. Treasuries are different from U.S. Treasuries. What the market is really wary of is the supply of duration risk, not the supply of the nominal value of U.S. Treasuries.

3. Let me ask you a question that everyone is concerned about but is not important: Will there be a peak in the maturity of U.S. Treasuries in the next few months?

Answer: The maturity is quite large but not extreme, and the maturity is mainly Tbills. There will not be a 6 trillion maturity peak in June

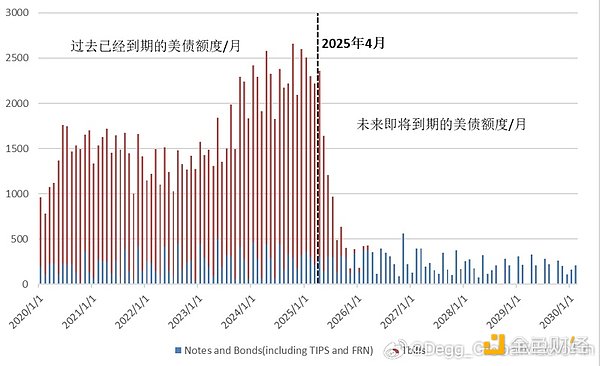

Explanation: The U.S. Treasury Department will regularly and in detail the future maturity of each outstanding U.S. Treasuries in its monthly fiscal report (Monthly Treasury Statement). According to the latest data, the amount of maturing bonds in April, June and June is 2.36 trillion, 1.64 trillion and 1.20 trillion respectively (Figure 2). The amount of maturing bonds in April is significantly lower than that in April, October and December 2024. It should be noted that since many tbills maturing in May and June have not actually been issued, and the issuance of tbills is not accurately announced in advance like long bonds, it is impossible to strictly estimate the actual amount of maturing bonds in May and June. However, there will not be a single-month maturity of 6 trillion in any case, because before the debt limit expires, the amount of additional issuance of US bonds cannot exceed the amount of US bonds maturing + the remaining funds of G Fund (i.e., extraordinary measure). If it is assumed that all the additional issuance of US bonds in April and May will mature in June, and then add the US bonds that have already matured in June, the total amount that can mature in June is theoretically 5.3 trillion. This is the theoretical limit. In fact, only a part of the additional issuance of US bonds in April and May will mature in June, and the actual amount of maturity in June is expected to be around 2 trillion.

4. Will the issuance of additional US debt after the debt limit is resolved trigger a liquidity crisis?

Answer: Not likely.

Explanation: There are several reasons.

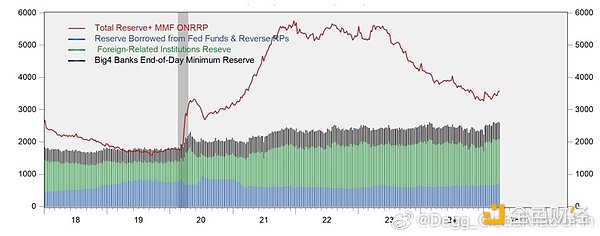

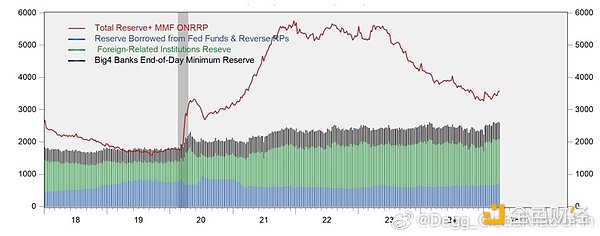

Reason 1: Most mainstream indicators show that the reserve balance of the US banking system is still hundreds of billions of dollars away from the level that triggers a "money shortage". Here we only cite an "effective excess reserve" indicator previously constructed by Zoltan in GMN 22, which is calculated by deducting inactive reserves (including overseas bank reserves + borrowed reserves + reserve safety cushions reserved by large banks at the end of the day to ensure intraday liquidity, currently totaling 2.6-2.7 trillion) at present, which is about 700 billion (Figure 3). This roughly means that the Ministry of Finance can replenish 700 billion TGA without triggering a money shortage.

Reason 2: The pace of the Treasury's bond issuance is adjustable. If it is found that the market demand for short-term bonds has obvious problems (reflected in the sharp rise in the issuance rate of Tbills along with the SOFR rate, that is, a cash shortage), the Ministry of Finance can completely reduce the issuance speed of Tbills and replenish TGA at a relatively moderate speed.

Reason 3: The Fed has slowed down the pace of QT in advance, and this time there is an SRF tool. Zoltan once had a very profound insight: the faster the balance sheet shrinkage, the deeper the V-shaped decline in the daily reserves of large banks, and the larger the reserve scale they need to set aside at the end of the day (also from GMN 22), and the higher the threshold for triggering a cash shortage. Since the Fed has slowed down the QT speed of US Treasury bonds to 5 billion/month, it can be almost considered that the balance sheet shrinkage has stopped, so the reserve threshold for cash shortages may have dropped. In addition, the Fed has long launched a standing repurchase facility (SRF) specifically to solve the problem of insufficient financing liquidity of primary dealers (PD) in the later stage of balance sheet shrinkage. Therefore, even if the TGA withdrawal leads to a decrease in the size of reserves, in theory, PD can easily seek financing from the Federal Reserve.

5. The real risk of US debt is not in the short term but in the long term

The real risk of US debt at present is not the short-term rolling refinancing risk. All the above-mentioned problems are technical problems. The technical bureaucrats of the Federal Reserve and the Treasury Department have rich experience in dealing with them, not to mention that the design of these mechanisms and response tools also involves the participation of TBAC (the top institutional player in the US Treasury market) and top scholars from various universities. Even if there is a problem, there is no political controversy for the Federal Reserve to take action to ensure the smooth operation of the bond market (for example, after SVB went bankrupt, it immediately launched BTFP, which provides liquidity at par rather than market value).

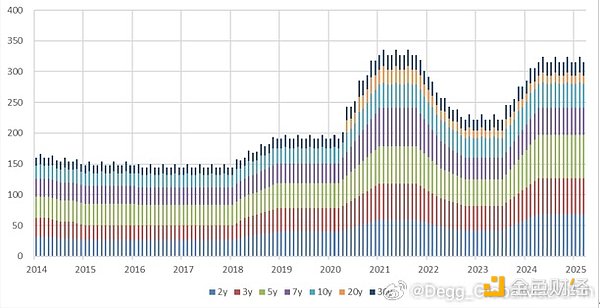

The real risk of US debt at present is the fermentation of long-term sustainable risks. On the one hand, it comes from Trump's extremely chaotic economic policies. If investors no longer trust the safe asset status of US Treasuries and the US dollar, US Treasuries will need to offer higher risk premiums to attract investors, which in itself will exacerbate fiscal sustainability concerns. On the other hand, it comes from the poor fiscal discipline of the Republicans. I believe that the most important macro information in the past month, apart from tariffs, is the joint budget bill formed by the two houses of Congress on April 10. It adds 5.3 trillion tax cuts (including 4 trillion TCJA extension) on a 10-year scale, but there is almost no spending cuts (Figure 4), completely abandoning the previous version of the House of Representatives' 10-year spending cut of 2 trillion (although 2 trillion is not much). If Republicans are unwilling to fulfill their promise to reduce spending in a relatively stable economic environment, then as the economy slows down or even declines, will Republicans cut spending significantly in fiscal 2026? Or will investors in the bond market pin their hopes on a divided Congress after the midterm elections, hoping that it can follow the example of 2011 and pass a fiscal discipline act (BCA) that may trigger a "fiscal cliff" to force spending cuts?

Of course, the sustainability of U.S. debt never means that U.S. debt will "hard default", because the 14th Amendment to the U.S. Constitution clearly stipulates that "the validity of the public debt of the United States, authorized by law, . . . shall not be questioned." (Once the money really cannot be repaid, Congress may require the Federal Reserve to purchase bonds directly to force repayment as it did during World War II), but from the continued depreciation of the US dollar exchange rate, the continued rise in residents' inflation expectations, and the much-watched Trump's dismissal of Federal Reserve Chairman Powell, the possibility of resolving the U.S. debt problem through "super-expected" inflation is increasing - just as the price fiscal theory (FTPL) predicts.

Tonight, we once again saw the triple kill of U.S. stocks, bonds and currencies and the surge in gold prices. This extremely rare phenomenon has been repeated frequently in the past few weeks. If this is not enough to alert every investor, politician and economist, I don't know what can.

Weiliang

Weiliang