Author: Paul Timofeev

Source: Shoal ResearchA Long-Overdue Change

In the financial services industry, a sector characterized by rigid systems, risk aversion, and heavy technical debt, innovation is often scarce. However, history shows that advances in financial infrastructure have always coincided with periods of exponential economic growth. Double-entry bookkeeping laid the foundation for modern accounting and credit systems; the emergence of joint-stock companies in the 17th century opened the door to large-scale investment and capital formation; and the Society for Worldwide Interbank Financial Telecommunication (SWIFT) and the Automated Clearing House (ACH) promoted the standardization of interbank transfers and cross-border payments. Global GDP growth has not slowed since the Industrial Revolution.

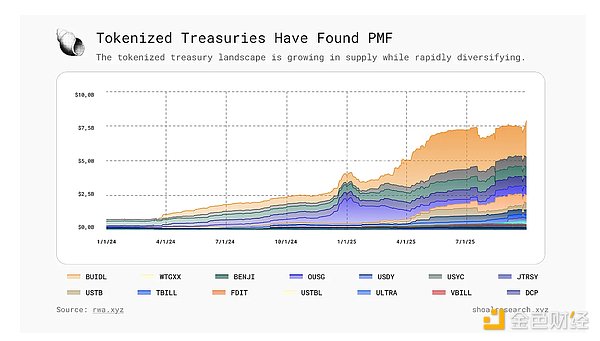

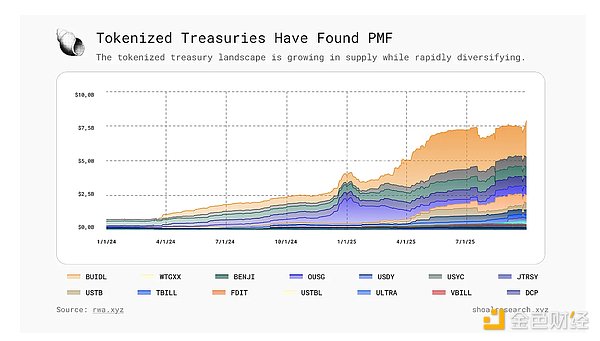

This naturally raises the question: where and how will the next opportunities for financial innovation emerge? As BlackRock and Fidelity put hundreds of billions of dollars into blockchain, landmark digital asset legislation continues to emerge, and even pension fund managers begin allocating funds to crypto assets, a clear trend is emerging: more and more forces are moving in the same direction: tokenization. At its core, tokenization involves encoding and deploying assets of economic value (cash, securities, real estate, etc.) and their associated ownership claims onto a blockchain. These distributed ledgers record every transaction as a transparent and immutable event, maintaining a single, synchronized source of truth across a decentralized network of nodes. Off-chain assets are represented by digital tokens; when ownership changes—that is, when assets are created, transferred, or destroyed—these changes are first verified by nodes and then permanently stored on-chain. Today, the most prominent and widely publicized example of this phenomenon is stablecoins. Stablecoins are designed to be anchored to the value of a stable reference asset (most commonly the US dollar) and are digital dollars issued and transferred on blockchain rails. They provide a stable, borderless unit of exchange in digital form: just as anyone with an internet connection can communicate with anyone around the world in seconds via WhatsApp, anyone can use stablecoins to transfer funds globally. Given that over 99% of stablecoins in circulation are backed by the US dollar, they can be considered "tokenized dollars": their on-chain supply is pegged 1:1 to reserves held in assets such as US dollars and Treasury bonds. Stablecoins have withstood the test of time, with issuance growing significantly, now totaling just over $300 billion. However, a comparison of monthly issuance of tokenized assets from five years ago and this year reveals that the market demand for tokenization extends far beyond digital dollars. To better understand why demand for tokenization is growing, it's helpful to first examine the limitations of current market infrastructure. Why does the financial industry need a new track? If there's one word to describe the state of current financial infrastructure, it's "old." The systems that move trillions of dollars daily—payment networks, clearing houses, and settlement systems—were largely designed over half a century ago. History doesn't simply repeat itself, but it often does. For much of the 20th century, American giants founded before 1935 dominated the market. But their advantage was gradually eroded by emerging competitors, with their market capitalization declining by approximately 2.2% annually. Then, in the 1970s, the emergence of new technologies, the oil crisis, and inflation broke this deadlock, and the rate of decline for these giants nearly doubled to 3.4% per year, sometimes surging to over 10%. That decade marked a structural turning point. Electronic systems, replacing paper-based transactions and manual clearing, ushered in a new era of efficiency, standardization, and economies of scale. Networks like SWIFT, ACH, and the Depository Trust & Clearing Corporation (DTCC) digitized the infrastructure of global markets, revolutionizing the flow and recording of capital. Yet, half a century later, the very systems that once powered market modernization have become bottlenecks hindering its development. The T+1 and T+2 Settlement Cycles Still in Use (and Even Longer) Today, most global securities markets still rely on delayed, multi-day settlement cycles, with the time between trade completion and final funds transfer typically taking one to two business days. A trade executed on Monday might not settle until Wednesday; a trade executed on Friday might not settle until the following week. The antiquity of this model is self-evident—it stems from the era of paper certificates, when transactions required physical delivery and manual reconciliation. Today, while trades can be completed electronically in seconds, the final transfer of asset ownership can still take days. Until settlement is complete, every trade is merely a record on a single institution's closed, private ledger. It would be naive to dismiss this structural delay as a simple operational inconvenience: delayed settlement is actually one of the largest hidden costs in global markets. Delays leave asset ownership uncertain, exposing participants to credit and counterparty risks, and tying up capital that could be used for productive investment. Overall, trillions of dollars are effectively idle and unproductive because the underlying infrastructure hasn't kept pace. DTCC reports that settlement failures total tens of billions of dollars daily. These failures are rarely isolated: when a security fails to settle on time, it may have already been used as collateral for another trade, causing a second trade to fail, potentially triggering a third, ultimately creating a chain reaction of settlement failures. The impact of this chain reaction is amplified in highly leveraged, illiquid markets. Even when trades are ultimately cleared, structural inefficiencies persist. Longer settlement cycles increase the amount of collateral required, as clearing houses demand higher margins to account for the added risk. Meanwhile, banks and brokers often struggle to determine which securities are truly available in real time, and settlement delays often lead to over-allocation of funds and disruptive inventory management. Furthermore, settlement systems cease operations when markets close, limiting their daily and weekly operating hours. These issues are exacerbated in cross-border transactions, where different regions maintain their own central securities depositories, each implementing different rules and timelines. Transferring assets across regions requires multiple intermediaries and reconciliation processes. A fragmented regulatory system adds another layer of hurdle: compliance requirements vary across jurisdictions, forcing firms to invest heavily in reconciliation and reporting. Market operating hours are rarely synchronized, leading to "blackout periods" when trading cannot proceed. A prime example is Europe's planned adoption of a T+1 settlement cycle until 2027, meaning EU markets will continue to be out of sync with those in the US and elsewhere, imposing new costs on participants operating across these markets. With this in mind, it's important to recognize that the evolution of financial infrastructure has often been reactive: In the 1960s, Wall Street's back-office paperwork burden led to the establishment of NASDAQ in 1971, the world's first electronic stock market. In 1973, the Depository Trust Company (DTC) established a centralized record-keeping system, completely eliminating the physical transfer of security certificates. After 9/11, Congress passed the Check Clearing for the 21st Century Act, allowing digital images to replace paper checks. In 2012, Hurricane Sandy flooded the DTCC's vaults, destroying 1.7 million security certificates and accelerating the transition to fully digital record-keeping. Infrastructure changes typically occur only when inefficiencies become entrenched or a crisis presents no alternative. History is repeating itself today. The shortcomings of today's market infrastructure are not abstract concepts; they translate directly into costs, user experience pain points, and risks, ultimately borne by end users. The internet has long enabled millisecond-level global transmission of information. If the technology for instant and continuous transfer already exists, why should funds and securities be constrained by regional ledgers and time-sensitive settlements? Value should flow as freely as information: globally accessible, operating 24/7, and secured by a transparent, programmable infrastructure—this is the natural progression. All roads lead to tokenization. Tokenization was designed to directly address the structural delays inherent in the modern financial system. By recording ownership and transfer information on a shared ledger, tokenization eliminates the need for multiple intermediaries to repeatedly reconcile the same transaction across decentralized databases. Settlement becomes a matter of adjusting balances on a digital ledger, rather than relaying instructions through layers of correspondent banks and clearing houses. The core resource consumed in this process is computing power, with the cost reflected in transaction fees (i.e., gas fees). With low or even near-zero gas fees now standard on blockchains, the marginal cost of transferring tokenized asset value will continue to approach zero. By contrast, traditional payment systems are still burdened with heavy institutional operating costs. A wire or ACH transfer may pass through multiple intermediaries—the sending bank, the receiving bank, the agency, and the clearing house—each of which incurs fees and adds settlement delays. Currently, the average transaction cost for global cross-border transfers remains as high as 6.49%, effectively a fixed tax on capital mobility. Tokenized rails largely eliminate this cost. The concept of asset tokenization is not new. It has resurfaced in various forms over the past decade. As early as 2012, Meni Rosenfeld's "Colored Coins" proposal was the first attempt to attach metadata to Bitcoin fragments to represent other assets such as stocks, bonds, and commodities—meaning that a digitally registered asset could contain both monetary value and external ownership claims. A few years later, Singapore's DigixDAO project attempted to bring physical assets like gold on-chain. Built on Ethereum and the InterPlanetary File System (IPFS), the project introduced a proof-of-origin model, allowing anyone to verify the authenticity of an asset through its custody chain. Digix was also one of the first projects to combine asset-backed tokens with decentralized autonomous organization (DAO) governance. However, the overall environment at the time was not yet ripe for scalable development. From 2017 to 2020, on-chain liquidity was extremely scarce, with many exchanges experiencing average daily trading volumes of less than $10 million. Bid-ask spreads for small-cap tokens often exceeded 4%-8%, resulting in unreliable price discovery and limiting the widespread adoption of tokenization. The supporting infrastructure required for tokenization—including custody, settlement, and compliance systems—is also immature. In 2018, there were only a handful of licensed custodians worldwide, and most lacked a clear regulatory position. The U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) noted that few institutions could meet the custody standards set forth in Section 206 (4)-2 of the Advisers Act, which leaves uncertainty surrounding asset segregation and custody. In addition, the access channels between banks and blockchains are unstable. As of 2020, the average failure rate for fiat-to-cryptocurrency conversions by mainstream institutions was close to 50% due to inconsistent KYC processes and frequent payment rejections. The diversity of infrastructure is also extremely limited: early entrants such as MoonPay, Ramp, and Transak only support less than 60 fiat currencies worldwide, excluding a large number of emerging markets and regions. Although the concept of tokenized finance itself is reasonable, the market lacks the necessary structure, incentive mechanisms, and trust systems to support institutional participation. Another five years passed before tokenization finally began to reach the scale it had originally envisioned, driven by advances in compliant custody technology, the rise of stablecoin liquidity, and the emergence of cross-chain settlement frameworks. The core principle of this revolution is liquidity. In any monetary system, highly divisible, low-friction assets tend to circulate rather than remain idle. Tokenized assets follow the same logic: they are designed to enable real-time flow, integration, and settlement across networks. Blockchain, as a public digital ledger, reduces the cost of asset transfer through automated reconciliation, while fractional ownership lowers the barrier to participation and deepens liquidity. The Current Tokenization Market Landscape: Currently, the total value of tokenized assets has surpassed $320 billion, spanning over 220 issuers and approximately 400,000 on-chain addresses. However, only a small fraction of this value is actively circulating within DeFi protocols. This gap highlights a key fact: the majority of tokenized assets today remain in custodial or permissioned environments, rather than freely composing and circulating on-chain. Setting aside these nuances in definition, the trend is clear: while still dwarfed by the $100 trillion-plus traditional market, tokenized assets have seen significant growth in value over the past year. The rise of tokenized assets has been most pronounced in two specific asset classes: stablecoins and tokenized government bonds. The Current State of Stablecoin Development Stablecoins remain the clearest proof-of-concept example of tokenization. With over $300 billion in circulation, stablecoins demonstrate the real demand and practical value of programmable, globally transferable, and 24/7 digital cash at scale. Over the past five years, stablecoin adoption has surged. Trillions of dollars have already flowed through stablecoins, and issuance continues to reach record highs. In terms of token type, issuance remains highly concentrated in USDT and USDC, which together account for the vast majority of the market share. New entrants such as FDUSD and PYUSD, backed by major exchanges and payment networks, signal a gradual shift by institutions toward compliant issuance. Tokens like DAI, USDS, and USDe demonstrate the persistent market demand for decentralized, DeFi-native stablecoins. In terms of blockchain distribution, Ethereum remains the leader in total stablecoin issuance and transaction value, but Tron, Solana, and Base are experiencing rapid growth. This distribution pattern reflects two different application scenarios of stablecoins: Ethereum dominates DeFi-related uses (such as liquidity pools, lending markets, and settlements); while Tron leads in peer-to-peer transfer volume, especially in emerging markets - its low fees and fast confirmation make it an ideal choice for payments and remittances. More notably, stablecoins are already impacting traditional payment networks. Currently, the average monthly transfer volume of stablecoins reaches trillions of US dollars, comparable to networks like Visa, Mastercard, and SWIFT. They also offer near-instant settlement speeds and significantly lower transaction costs. The regulatory landscape surrounding stablecoins is also evolving. The emergence of a new class of compliant money market fund (MMF) tokens—such as BUIDL, BENJI, and USDtb—and Cap Money, which integrates these tokens, demonstrates the convergence of stablecoin designs with traditional cash management structures. These instruments, combining the accessibility of stablecoins with the yield of government bonds, offer guidance for the next phase of tokenized asset development. If stablecoins provide a blueprint for tokenization, then government bonds are emerging as the rising star of the tokenization landscape. As of this writing, tokenized government bonds have surpassed $8 billion, representing over 80% growth so far this year. This growth rate, far exceeding the early trajectory of stablecoins, reflects the growing demand for interest-bearing, low-risk assets that can serve as collateral and liquidity in global markets.

Overall, the current tokenized treasury bond market has the following scale (data source: rwa.xyz):

Catherine

Catherine