Key Points

A 25 basis point rate cut was dissented by Milan, who preferred a 50 basis point cut. Cook did not dissent.

Not much information was provided regarding the timetable for balance sheet reduction.

The meeting contained few unexpected surprises, and the market experienced some moderate volatility.

The US dollar was a winner, gold was a loser, and the 10-year Treasury bond rebounded after breaking below the 4% level.

At the press conference, Powell looked overly composed and seemed out of form. Reporters' questions focused on employment data, tariffs, and independence. On the question of independence, Powell's rhetoric was tough, he was hesitant when mentioning members of the Trump faction, and he seemed somewhat dismissive. He noted that independence is ingrained in the Fed's culture and is in its DNA. Regarding the balanced risk stance, the Fed's rhetoric leaned more heavily toward employment risks, which is understandable given recent unfavorable data. Overall, the tone was neutral, with a slight hawkish edge. FOMC Statement

Recent indicators suggest that the growth of economic activity slowed in the first half of this year. Job growth decelerated, and the unemployment rate rose slightly but remained low. Inflation has increased somewhat and remains elevated.

The Committee seeks to achieve maximum employment and 2 percent inflation in the longer run. Uncertainty about the economic outlook remains considerable.

FOMC Statement

Recent indicators suggest that the growth of economic activity slowed in the first half of this year.

Members voting in favor of the monetary policy action were: Jerome H. Powell, Chairman; John C. Williams, Vice Chairman; Michael S. Barr; Michelle W. Bowman; Susan M. Collins; Lisa D. Cook; Austan D. Goolsbee; Philip N. Jefferson; Alberto G. Musallem; Jeffrey R. Schmid; and Christopher J. Waller.

Stephen I. Milan voted against the action, preferring to lower the target range for the federal funds rate by 1/2 percentage point at this meeting.

Members voting in favor of lowering the target range for the federal funds rate by 1/2 percentage point at this meeting.

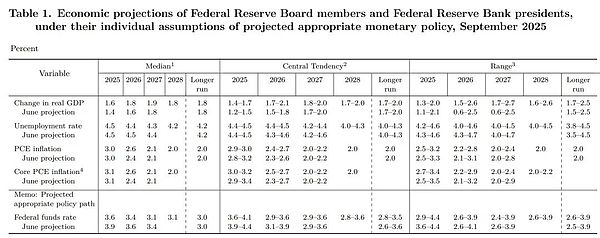

Economic Forecast

Bitmap

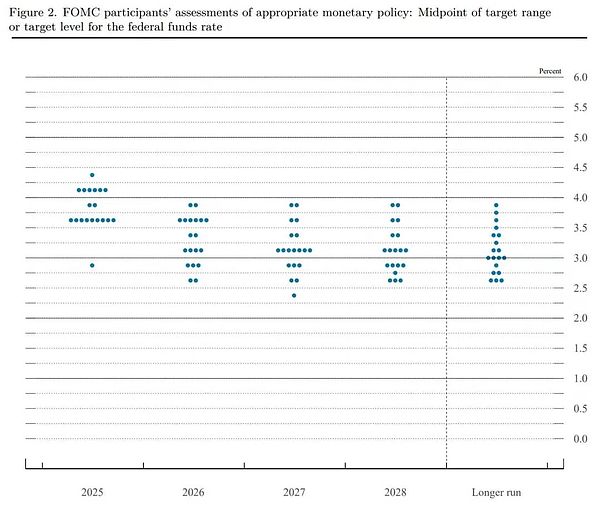

mostly by companies that sit between exporters and consumers. So if you buy something and then sell it to a retailer, or you use it to make a product, you're probably bearing most of those costs and not being able to pass them all on to consumers. at this point. That seems to be what we're seeing. All of these companies and entities in the middle, they'll tell you they fully intend to pass these costs on in the future, but they're not doing that right now. The pass-through to consumers has been minimal. It's been slower and smaller than we thought. But the evidence is very clear that there's been some pass-through. Questioner: I also wanted to ask if you could share with us under what conditions you might consider leaving the Fed in May. Powell: I have nothing new on that for you today. Questioner: Hi, Katerina Sariva from Bloomberg. I just wanted to follow up on a response you made a few minutes ago. We often hear you talk about how you and your colleagues don't consider politics. That doesn't enter the room. But one of your new colleagues does come from a world where everything is viewed through the lens of politics and which party benefits. And that person is still employed by the White House. How are the markets and the public interpreting, for example, some of his speeches and some of the forecasts we're seeing today? I mean, the median forecast for this year has been moved by his introduction. I'm talking about the number of rate cuts expected this year. What would you say to the markets and the public trying to interpret what you're saying? Powell: There are 19 participants, and 12 of them vote on a rotating basis. So there's no single voter, and the only way you can really move things is to be extremely persuasive. And in the context of our work, the only way to do that is to make a very strong argument based on the data and one's understanding of the economy. That's what really matters. And that's how it works. I think that's the way this institution is; it's in its DNA. That's not going to change. Questioner: And then I want to ask about a Gallup poll that shows that Americans now have more confidence in the president than in the Federal Reserve to do the right thing for the economy. Why do you think that is? What's your response? What's your message to the public? Powell: Our response is that we will do everything we can to use the tools that we have to achieve the goals that Congress has given us, and we won't be distracted by anything. So I think that's what we're going to do. We're just going to keep doing our jobs. Question: Claire Jones of the Financial Times. Given the range of views expressed before the meeting, I think today's meeting was much less divided than many expected. It would be interesting to know what you think drove such a strong consensus at the meeting, and on the other hand, could you explain why the dot plot was so scattered across the board, ranging from some even expecting higher rates by the end of the year to five rate cuts. What kind of range of views did you hear, and why, on the one hand, was there so much support for a rate cut today, and on the other hand, why was there such a wide divergence about what would happen next? POWELL: So I think there's been a pretty broad reaction, a broad assessment that things have changed about the labor market. Even though we could and did say at the July meeting that the labor market was solid, and we could point to 150,000 jobs a month and a lot of other things, I think the new data that we've gotten, not just the nonfarm payroll data but other data as well, suggests that there are indeed meaningful downside risks. I said there were downside risks then, but I think that downside risk has now materialized, and there's clearly more downside risks. So I think that's been widely accepted. And that means different things to different people. Some people, almost everyone wrote in favor of this rate cut, some people supported more rate cuts, and some people didn't, as you can see from the dot plot. That's the situation. I mean, people have a lot of experience with this. I think that's the situation. I think that's the situation. I think that's the situation. I think you have people who take this job very seriously and have been thinking about it, doing their work, and discussing it with our colleagues. We discussed this endlessly among ourselves, and then we met and laid everything out on the table, and this is what you get. You're right. There's a wide range of views in the dot plot, which I think, as I said, is unsurprising given the rather unusual, historically unusual nature of the challenges we face. But let's remember, unemployment is 4.3%. The economy is growing at 1.5%. So this isn't a bad economy or anything like that. We've seen more challenging economic times. But from a policy perspective, from the perspective of what we're trying to accomplish, knowing what to do is challenging. As I mentioned earlier, there's no risk-free path. What to do isn't immediately obvious. So we have to keep a close eye on inflation. At the same time, we can't lose sight of, and we have to keep a close eye on, maximum employment. Those are our two co-equal goals, and you'll see a range of views on what to do. Despite this, we came together in this meeting today and acted with great unity. QUESTIONER: Thank you, Archie Hall of The Economist. You mentioned earlier that job creation is falling short of your guess at its "break-even" rate. I'm curious to know a little more about that. Where do you think that "break-even" rate is? POWELL: You know, there are lots of different ways to calculate it, and none of them are perfect. But you know, it's clearly fallen significantly. You could say it's between zero and 50,000, and you could be right or wrong. I mean, there are just lots of different ways. So wherever it was a few months ago, 150,000, 200,000, it's down quite a bit, quite significantly, and that's because there are very few people joining the labor force. There's really not a lot of growth in the labor force right now, and that's been the main source of labor supply for the past two or three years. So we don't have that anymore. We also have a lot lower demand. You know, what's interesting is that supply and demand have really been falling together so far, except now we do have inflation, sorry, it's the unemployment rate that's up, just a little bit above its year-round range. 4.3% is still a low level, but... you know, I think the fact that both supply and demand have fallen so quickly has certainly caught everyone's attention. Questioner: You mentioned a lot about downside risks to employment, but what's striking is that the activity and output indicators we have for the third quarter seem quite strong. The Atlanta Fed's GDPNow model is very strong, and you mentioned the strong PCE data as well. How do you reconcile those things? If those activity indicators are correct, are there any upside risks to the labor market? POWELL: Well, that's great. We'd love to see that. So I don't know if you see a big contradiction there, but it's comforting to see that economic activity is holding steady. A lot of that is coming from consumption. It looks like consumption is stronger than expected, and that's what we got data on earlier this week, I think. And we also have a fairly narrow sector that's generating a lot of economic activity, and that's AI construction and business investment. So we look at all of that, and I would say we did revise upward. Between the June and September SEPs, the median growth for the year was actually revised upward, while inflation and the labor market didn't change much. And what really became the focus today was the risks we see in the labor market. Questioner: Hello, Nicole Goodkind from Barron's. Thank you for taking my question. Given the cumulative impact of high interest rates on the real estate industry, I'm wondering how concerned you are that current interest rate levels are exacerbating housing affordability issues and potentially hindering household formation and wealth accumulation for a segment of the population. Powell: You know, housing is an interest rate-sensitive activity, so it's at the heart of monetary policy. When the pandemic hit and we cut interest rates to zero, real estate companies were very grateful. They really said that was the only thing that allowed them to continue operating, which was that we were so aggressive in cutting rates and providing credit and things like that, and they were able to finance because we did that. The flip side is that when inflation gets higher and we raise interest rates, you're right, that does put a burden on the housing sector. So interest rates have come down a bit, and as that's happening, we don't set mortgage rates, but changes in our policy rate do affect mortgage rates, and that's already happening, which of course will increase demand, and lowering borrowing rates for builders will help, you know, help builders' supply, so some of that should happen. I think most analysts agree that it takes a pretty significant change in interest rates to have a significant impact on the housing sector, and, you know, another thing is that a strong economy, with maximum employment and stable prices, is a good economy for housing. Finally, I would say there's a deeper issue here that's not a cyclical issue that the Fed can address, and that's the nationwide housing shortage, or the fact that there simply aren't enough homes for people in many parts of the country. And, you know, all the areas around metro areas like Washington, D.C., are built very densely. So you have to build further and further out. That's the situation. Q: Just a quick follow-up question. At your last press conference after the September 10 meeting, you seemed to suggest that policymakers lacked confidence in their forecasts. I'm wondering if you still feel that way. POWELL: You know, forecasting is incredibly difficult, even in calm times. As I mentioned before, forecasters are a humble bunch, with a lot to be humble about. So I think this is a particularly challenging time, with even more uncertainty than usual. So I don't know any forecaster anywhere, really. Ask any forecaster if they have a lot of confidence in their forecasts right now. I think they'd honestly say no. Questioner: Thank you, Chairman Powell. Jennifer Schoenberger of Yahoo Finance. If you're cutting rates, why do you continue to shrink your balance sheet and then pause it? Powell: Well, I think we're, you know, shrinking the balance sheet very limitedly right now. As you know, we remain in a position of ample reserves on the balance sheet, and we said we would stop at just above ample reserves. We are there. And we're, you know, approaching that level. We're monitoring it very carefully. We don't believe it's having any significant macroeconomic impact. These are fairly small numbers moving within a massive economy. You know, the level of contraction isn't very large. So I wouldn't attribute macroeconomic consequences to this. Q: In his recent confirmation hearing, Stephen Milan mentioned that the Federal Reserve actually has a three-pronged mandate given by Congress: not just employment and stable prices, but also moderate long-term interest rates. So what does Congress mean by "modest long-term interest rates"? And how should we interpret changes in the 10-year Treasury yield? How do you think about this part of the mandate when policy choices like rate cuts or balance sheet reduction affect the long end of the yield curve? POWELL: We've always thought of it as a dual mandate, maximum employment and price stability, and that's been the case for a long time, because we thought that moderate long-term interest rates were a consequence of stable inflation, low and stable inflation, and maximum employment. So for a long time, we didn't think of it as a third mandate that required independent action. That's the case. And, as far as I'm concerned, there's no consideration that we incorporate it in some different way. Q: Thank you, Chairman Powell. Matt Egan, CNN. We recently learned that the average FICO credit score has dropped two points this year, the largest drop since the Great Recession of 2009, and delinquency rates are high on auto loans, personal loans, and credit cards. How concerned are you about the health of consumers' finances, if at all? Do you expect today's rate cut to help? POWELL: So, you know, we're aware of that. I think delinquencies have been rising, and we're certainly watching. They haven't reached a level, and I don't think they've reached a level that's very concerning overall, but it's something we're watching. You know, lower interest rates should support economic activity. I don't know if one rate cut will have a measurable impact on that, but over time, you know, a strong economy with a strong labor market is what we're aiming for, and stable prices, so that should help. Questioner: First, this rate cut comes at a time when the stock market is at or near all-time highs and some valuation measures are historically elevated. Is there a risk that this rate cut could overheat financial markets and potentially fuel a bubble? Powell: We are closely focused on our goals, which are maximum employment and price stability. So the actions we take are all aimed at those goals. So, we did what we did today. In addition, we monitor financial stability very, very carefully. And, you know, I would say it's a mixed picture, but households are in good shape. Banks are in good shape. Overall, households, overall, remain in good shape. I know that people at the lower end of the income spectrum are clearly feeling the pinch. But from a financial stability perspective, we monitor the entire picture. We don't think there's a right or wrong future level of asset prices. We don't think there's a right or wrong price level for specific financial assets, but we monitor the entire picture and really look for structural vulnerabilities, and I would say those are not elevated right now. Questioner: Hello, Chairman Powell. Jen Young with M&I Markets News. I wanted to ask you about inflation expectations. You said the Fed can't take the stability of inflation expectations for granted. You mentioned that they've risen in the short term. I wonder if you could talk about that. And then looking longer term, I'm wondering if you see any evidence that the debate over Fed independence and the growing deficit are putting pressure on inflation expectations? Powell: As you said, short-term inflation expectations tend to react to near-term inflation. So if inflation rises, inflation expectations predict that it will take a while to fall back. Unfortunately, throughout this period, long-term inflation expectations, whether it's the break-even inflation rate in the market or in almost all long-term surveys, with the University of Michigan survey being a bit of an exception recently, have been remarkably stable, at levels consistent with 2% inflation over the long run. So we don't take that for granted. We actually assume that our actions have a real impact on that, and we need to continually demonstrate and talk about our commitment to 2% inflation. So you'll hear us do that. But as I mentioned, it's a difficult situation because the risks we face affect both the labor market and inflation. Those are our two objectives. So we have to balance that. And that's really what we're trying to do. Part of your question was about independence. I don't see market participants, I don't see them factoring that into their rate setting right now.

mostly by companies that sit between exporters and consumers. So if you buy something and then sell it to a retailer, or you use it to make a product, you're probably bearing most of those costs and not being able to pass them all on to consumers. at this point. That seems to be what we're seeing. All of these companies and entities in the middle, they'll tell you they fully intend to pass these costs on in the future, but they're not doing that right now. The pass-through to consumers has been minimal. It's been slower and smaller than we thought. But the evidence is very clear that there's been some pass-through. Questioner: I also wanted to ask if you could share with us under what conditions you might consider leaving the Fed in May. Powell: I have nothing new on that for you today. Questioner: Hi, Katerina Sariva from Bloomberg. I just wanted to follow up on a response you made a few minutes ago. We often hear you talk about how you and your colleagues don't consider politics. That doesn't enter the room. But one of your new colleagues does come from a world where everything is viewed through the lens of politics and which party benefits. And that person is still employed by the White House. How are the markets and the public interpreting, for example, some of his speeches and some of the forecasts we're seeing today? I mean, the median forecast for this year has been moved by his introduction. I'm talking about the number of rate cuts expected this year. What would you say to the markets and the public trying to interpret what you're saying? Powell: There are 19 participants, and 12 of them vote on a rotating basis. So there's no single voter, and the only way you can really move things is to be extremely persuasive. And in the context of our work, the only way to do that is to make a very strong argument based on the data and one's understanding of the economy. That's what really matters. And that's how it works. I think that's the way this institution is; it's in its DNA. That's not going to change. Questioner: And then I want to ask about a Gallup poll that shows that Americans now have more confidence in the president than in the Federal Reserve to do the right thing for the economy. Why do you think that is? What's your response? What's your message to the public? Powell: Our response is that we will do everything we can to use the tools that we have to achieve the goals that Congress has given us, and we won't be distracted by anything. So I think that's what we're going to do. We're just going to keep doing our jobs. Question: Claire Jones of the Financial Times. Given the range of views expressed before the meeting, I think today's meeting was much less divided than many expected. It would be interesting to know what you think drove such a strong consensus at the meeting, and on the other hand, could you explain why the dot plot was so scattered across the board, ranging from some even expecting higher rates by the end of the year to five rate cuts. What kind of range of views did you hear, and why, on the one hand, was there so much support for a rate cut today, and on the other hand, why was there such a wide divergence about what would happen next? POWELL: So I think there's been a pretty broad reaction, a broad assessment that things have changed about the labor market. Even though we could and did say at the July meeting that the labor market was solid, and we could point to 150,000 jobs a month and a lot of other things, I think the new data that we've gotten, not just the nonfarm payroll data but other data as well, suggests that there are indeed meaningful downside risks. I said there were downside risks then, but I think that downside risk has now materialized, and there's clearly more downside risks. So I think that's been widely accepted. And that means different things to different people. Some people, almost everyone wrote in favor of this rate cut, some people supported more rate cuts, and some people didn't, as you can see from the dot plot. That's the situation. I mean, people have a lot of experience with this. I think that's the situation. I think that's the situation. I think that's the situation. I think you have people who take this job very seriously and have been thinking about it, doing their work, and discussing it with our colleagues. We discussed this endlessly among ourselves, and then we met and laid everything out on the table, and this is what you get. You're right. There's a wide range of views in the dot plot, which I think, as I said, is unsurprising given the rather unusual, historically unusual nature of the challenges we face. But let's remember, unemployment is 4.3%. The economy is growing at 1.5%. So this isn't a bad economy or anything like that. We've seen more challenging economic times. But from a policy perspective, from the perspective of what we're trying to accomplish, knowing what to do is challenging. As I mentioned earlier, there's no risk-free path. What to do isn't immediately obvious. So we have to keep a close eye on inflation. At the same time, we can't lose sight of, and we have to keep a close eye on, maximum employment. Those are our two co-equal goals, and you'll see a range of views on what to do. Despite this, we came together in this meeting today and acted with great unity. QUESTIONER: Thank you, Archie Hall of The Economist. You mentioned earlier that job creation is falling short of your guess at its "break-even" rate. I'm curious to know a little more about that. Where do you think that "break-even" rate is? POWELL: You know, there are lots of different ways to calculate it, and none of them are perfect. But you know, it's clearly fallen significantly. You could say it's between zero and 50,000, and you could be right or wrong. I mean, there are just lots of different ways. So wherever it was a few months ago, 150,000, 200,000, it's down quite a bit, quite significantly, and that's because there are very few people joining the labor force. There's really not a lot of growth in the labor force right now, and that's been the main source of labor supply for the past two or three years. So we don't have that anymore. We also have a lot lower demand. You know, what's interesting is that supply and demand have really been falling together so far, except now we do have inflation, sorry, it's the unemployment rate that's up, just a little bit above its year-round range. 4.3% is still a low level, but... you know, I think the fact that both supply and demand have fallen so quickly has certainly caught everyone's attention. Questioner: You mentioned a lot about downside risks to employment, but what's striking is that the activity and output indicators we have for the third quarter seem quite strong. The Atlanta Fed's GDPNow model is very strong, and you mentioned the strong PCE data as well. How do you reconcile those things? If those activity indicators are correct, are there any upside risks to the labor market? POWELL: Well, that's great. We'd love to see that. So I don't know if you see a big contradiction there, but it's comforting to see that economic activity is holding steady. A lot of that is coming from consumption. It looks like consumption is stronger than expected, and that's what we got data on earlier this week, I think. And we also have a fairly narrow sector that's generating a lot of economic activity, and that's AI construction and business investment. So we look at all of that, and I would say we did revise upward. Between the June and September SEPs, the median growth for the year was actually revised upward, while inflation and the labor market didn't change much. And what really became the focus today was the risks we see in the labor market. Questioner: Hello, Nicole Goodkind from Barron's. Thank you for taking my question. Given the cumulative impact of high interest rates on the real estate industry, I'm wondering how concerned you are that current interest rate levels are exacerbating housing affordability issues and potentially hindering household formation and wealth accumulation for a segment of the population. Powell: You know, housing is an interest rate-sensitive activity, so it's at the heart of monetary policy. When the pandemic hit and we cut interest rates to zero, real estate companies were very grateful. They really said that was the only thing that allowed them to continue operating, which was that we were so aggressive in cutting rates and providing credit and things like that, and they were able to finance because we did that. The flip side is that when inflation gets higher and we raise interest rates, you're right, that does put a burden on the housing sector. So interest rates have come down a bit, and as that's happening, we don't set mortgage rates, but changes in our policy rate do affect mortgage rates, and that's already happening, which of course will increase demand, and lowering borrowing rates for builders will help, you know, help builders' supply, so some of that should happen. I think most analysts agree that it takes a pretty significant change in interest rates to have a significant impact on the housing sector, and, you know, another thing is that a strong economy, with maximum employment and stable prices, is a good economy for housing. Finally, I would say there's a deeper issue here that's not a cyclical issue that the Fed can address, and that's the nationwide housing shortage, or the fact that there simply aren't enough homes for people in many parts of the country. And, you know, all the areas around metro areas like Washington, D.C., are built very densely. So you have to build further and further out. That's the situation. Q: Just a quick follow-up question. At your last press conference after the September 10 meeting, you seemed to suggest that policymakers lacked confidence in their forecasts. I'm wondering if you still feel that way. POWELL: You know, forecasting is incredibly difficult, even in calm times. As I mentioned before, forecasters are a humble bunch, with a lot to be humble about. So I think this is a particularly challenging time, with even more uncertainty than usual. So I don't know any forecaster anywhere, really. Ask any forecaster if they have a lot of confidence in their forecasts right now. I think they'd honestly say no. Questioner: Thank you, Chairman Powell. Jennifer Schoenberger of Yahoo Finance. If you're cutting rates, why do you continue to shrink your balance sheet and then pause it? Powell: Well, I think we're, you know, shrinking the balance sheet very limitedly right now. As you know, we remain in a position of ample reserves on the balance sheet, and we said we would stop at just above ample reserves. We are there. And we're, you know, approaching that level. We're monitoring it very carefully. We don't believe it's having any significant macroeconomic impact. These are fairly small numbers moving within a massive economy. You know, the level of contraction isn't very large. So I wouldn't attribute macroeconomic consequences to this. Q: In his recent confirmation hearing, Stephen Milan mentioned that the Federal Reserve actually has a three-pronged mandate given by Congress: not just employment and stable prices, but also moderate long-term interest rates. So what does Congress mean by "modest long-term interest rates"? And how should we interpret changes in the 10-year Treasury yield? How do you think about this part of the mandate when policy choices like rate cuts or balance sheet reduction affect the long end of the yield curve? POWELL: We've always thought of it as a dual mandate, maximum employment and price stability, and that's been the case for a long time, because we thought that moderate long-term interest rates were a consequence of stable inflation, low and stable inflation, and maximum employment. So for a long time, we didn't think of it as a third mandate that required independent action. That's the case. And, as far as I'm concerned, there's no consideration that we incorporate it in some different way. Q: Thank you, Chairman Powell. Matt Egan, CNN. We recently learned that the average FICO credit score has dropped two points this year, the largest drop since the Great Recession of 2009, and delinquency rates are high on auto loans, personal loans, and credit cards. How concerned are you about the health of consumers' finances, if at all? Do you expect today's rate cut to help? POWELL: So, you know, we're aware of that. I think delinquencies have been rising, and we're certainly watching. They haven't reached a level, and I don't think they've reached a level that's very concerning overall, but it's something we're watching. You know, lower interest rates should support economic activity. I don't know if one rate cut will have a measurable impact on that, but over time, you know, a strong economy with a strong labor market is what we're aiming for, and stable prices, so that should help. Questioner: First, this rate cut comes at a time when the stock market is at or near all-time highs and some valuation measures are historically elevated. Is there a risk that this rate cut could overheat financial markets and potentially fuel a bubble? Powell: We are closely focused on our goals, which are maximum employment and price stability. So the actions we take are all aimed at those goals. So, we did what we did today. In addition, we monitor financial stability very, very carefully. And, you know, I would say it's a mixed picture, but households are in good shape. Banks are in good shape. Overall, households, overall, remain in good shape. I know that people at the lower end of the income spectrum are clearly feeling the pinch. But from a financial stability perspective, we monitor the entire picture. We don't think there's a right or wrong future level of asset prices. We don't think there's a right or wrong price level for specific financial assets, but we monitor the entire picture and really look for structural vulnerabilities, and I would say those are not elevated right now. Questioner: Hello, Chairman Powell. Jen Young with M&I Markets News. I wanted to ask you about inflation expectations. You said the Fed can't take the stability of inflation expectations for granted. You mentioned that they've risen in the short term. I wonder if you could talk about that. And then looking longer term, I'm wondering if you see any evidence that the debate over Fed independence and the growing deficit are putting pressure on inflation expectations? Powell: As you said, short-term inflation expectations tend to react to near-term inflation. So if inflation rises, inflation expectations predict that it will take a while to fall back. Unfortunately, throughout this period, long-term inflation expectations, whether it's the break-even inflation rate in the market or in almost all long-term surveys, with the University of Michigan survey being a bit of an exception recently, have been remarkably stable, at levels consistent with 2% inflation over the long run. So we don't take that for granted. We actually assume that our actions have a real impact on that, and we need to continually demonstrate and talk about our commitment to 2% inflation. So you'll hear us do that. But as I mentioned, it's a difficult situation because the risks we face affect both the labor market and inflation. Those are our two objectives. So we have to balance that. And that's really what we're trying to do. Part of your question was about independence. I don't see market participants, I don't see them factoring that into their rate setting right now.

JinseFinance

JinseFinance

JinseFinance

JinseFinance Wilfred

Wilfred JinseFinance

JinseFinance JinseFinance

JinseFinance cryptopotato

cryptopotato Bitcoinist

Bitcoinist Cointelegraph

Cointelegraph Cointelegraph

Cointelegraph Cointelegraph

Cointelegraph Cointelegraph

Cointelegraph