Author: Pavel, Source: Hazeflow, Compiler: Shaw Golden Finance

Abstract

We are considering whether destroying or redistributing assets is more conducive to maintaining a healthy system and aligning incentives.

When slashing is the initial stage of punishing malicious behavior, redistributing assets is often more effective than destroying them directly.

When destruction is a core feature of the design and does not involve slashing (such as in a deflationary economy), there is no reason to implement redistribution.

When redistribution is a core feature of the design but appears more like a vulnerability, there is no reason to replace it with destruction; improvements must be made at a fundamental level.

Definition

Many people seem confused and believe that when a token is slashed, the slashed shares are automatically destroyed, resulting in a decrease in supply. This is not the case.

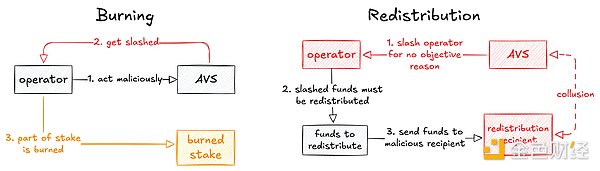

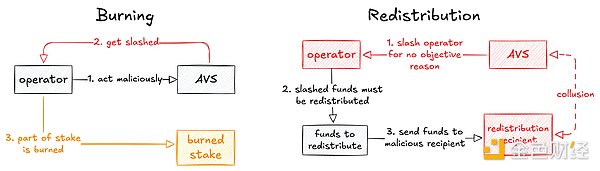

"Slashing" describes the "taking" of assets from a malicious actor, while "burning" and "reallocation" describe what happens to the assets after they are taken. As we've discussed before, they can either be destroyed or redistributed: one action reduces the total supply, while the other transfers value to another party (not always to the detriment of the other). Due to the protocol's built-in mechanism design, destruction can also occur without slashing. Redistribution contributes to economic security. Let's take EigenCloud, one of the most prominent protocols in the cryptocurrency space, as an example. Here, operators face slashing of rewards if they fail to meet their obligations, which is a good thing: bad actors are punished. However, before a redistribution mechanism for slashed funds was introduced, these funds were permanently destroyed (and may still be destroyed today). We believe that destroying slashed funds in such a system is tantamount to shooting oneself in the foot. When an operator's stake is slashed, the operator is penalized (for good reason), but: The injured party receives no compensation for the harm they incurred (imagine being hit by a car and the driver is jailed and penalized, but you receive no help). The system becomes less secure (because there are now fewer assets protecting it). So why destroy the value and shoot yourself in the foot when we can just keep it and transfer it to the injured party? Trustworthy parties can increase their rewards, compromised users can be compensated, and value remains in the ecosystem; it's simply redistributed. This can also unlock a vast array of use cases for applications. New on-chain insurance protocols have the potential to operate correctly in a permissionless manner. Faster, more reliable DEX transactions will compensate traders if trade requests fail, expire, or aren't completed on time. This will further incentivize operators to operate honestly and transparently. Lenders will be protected through a guaranteed annual percentage rate (APR), greater transparency, and potentially fixed interest rates in the native currency. Economic security not only directly protects users before an incident (e.g., through burn mechanisms), but also directly protects users after it occurs. Protocols like Cap already implement redistribution mechanisms where slashed operator funds are redistributed to affected cUSD holders. It's not without its drawbacks. Burning assets is easier than redistributing them because you don't have to worry about what happens to the assets; they're simply destroyed, and no one benefits. Burning assets offers fewer benefits and significantly lower risks. Redistribution, on the other hand, significantly changes the rules of the game, and its implementation (confiscating assets from bad actors and redistributing them to the damaged parties) is not as simple as it seems. A malicious operator can now join forces with a malicious validator set (AVS). Currently, the AVS can implement any custom slashing logic, even if it's unfair or biased. With slashing mechanisms in place, malicious AVS actions become moot because operators won't stake their assets if they know they might be slashed for no reason. Through reallocation, the AVS can transfer an operator's stake to malicious operators (who collude), thereby extracting value from the system. The same thing happens if the AVS keys are compromised, which also affects the overall "attractiveness" of the operator or AVS.

Additional evaluation of the mechanism design is needed here. Operators should not have the option to "switch types" after creation. Instead, there should be a way to identify compromised (malicious) operators and redistribute value when it falls into their hands, as well as ongoing monitoring, etc.

While destroying funds would be much easier and redistributing more fairly, it requires additional complexity. Solving the Problem of Mal-Redistribution Maximum Extractable Value (MEV) can be viewed from this perspective: innocent users and liquidity providers (LPs) suffer losses for no apparent reason. When users want to swap assets, they may be front-run or squeezed, resulting in a worse trade outcome (price). We can safely say that they suffer losses because they invested stake (the asset to be swapped) into the system (DEX), held it for a period of time (the swap time), and ultimately received far less than they should have received. There are two core issues here: LPs are being slashed for no apparent reason (they didn't act maliciously).

Users are slashed for no reason; they acted without malicious intent or even with the intention of profiting or doing good for the system, they simply wanted their actions to be executed.

Here, value is extracted and redistributed, with the exploiters being rewarded and parties who have done nothing wrong being hammered.

This problem can be more easily addressed by users through the creation of certain sorting rules, such as Arbitrum Boost.

For LPs, this problem is compounded, as they are often victims of leverage ratios (losses vs. rebalancing). Can this be solved by burning? Burning can provide broad benefits to all token holders without specifically compensating liquidity providers who directly suffer losses from arbitrage activities. Technically, this problem can be solved by burning; once profits are destroyed, there's no incentive for arbitrage. However, once arbitrage profits are extracted, identifying them becomes more difficult: while on-chain transactions are visible, CEX data doesn't reveal the exact addresses of the traders. In this case, poor redistribution design can be addressed through application-specific ordering, allowing liquidity providers to capture value that would otherwise be taken away by speculators. This is one of the solutions implemented by Angstrom, and it works quite well. In the specific case of MEV, neither redistribution nor burning is a viable option; they only address the symptoms, not the root cause. Changes must occur at a fundamental level. Burning May Be Better Than Redistribution We want to emphasize that redistribution is not a panacea and cannot always replace burning. When slashing (Phase 1) is not involved, burning funds is a key feature of mechanism design in most cases. For example, BNB tokens are burned quarterly, a core feature of a deflationary token economics model. In this model, redistribution is impossible because the process involves neither exploiters nor compromised users. A similar process occurs in Ethereum (EIP-1559), where basefees are burned, creating a deflationary effect. Given Ethereum's mechanism design, fees can become very high during periods of network congestion. Rather than burning basefees, one might argue that instead of burning them, basefees should be transferred to a treasury fund to offset some of the costs during periods of network congestion. However, the downsides far outweigh the potential benefits: Redistributing fees could weaken the deflationary effect, leading to higher inflation and potentially depressing token value over time. Funds could be misallocated, reducing revenue (how should the fund prioritize which transactions to fund? Does it make sense to pay priority fees when users can be compensated with funds? etc.). It might be easier to spam and cause greater congestion if you know your fees will be funded. Hypothetically, redistributing Ethereum's base fees to stakers could incentivize validators to prioritize high-fee transactions over those that haven't been funded or whose fees were paid in advance. There are many other scenarios, but the key point is that redistribution is not a panacea. If destruction happens on its own (without prior slashing), then there's little reason to replace it with reallocation.

Conclusion

Finally, we'd like to note that reallocation is generally less effective than destruction when no upfront slashing is involved, and generally works better than destruction when slashing is involved.

The incentive alignment problem is a long-standing one in cryptocurrency and often varies from protocol to protocol. If economic value directly impacts the security or other critical aspects of the system, then it's better not to destroy that value, but to find a way to correctly redistribute it to those who act honestly, thereby incentivizing fair and honest behavior.

Anais

Anais