Author: Lyn Alden, Investment Analyst; Translator: AIMan@Golden Finance

The persistence of deficits has a variety of impacts on investments, but it is important not to be distracted by illogical things in the process.

Fiscal Debt and Deficit 101

Before I dive into these misunderstandings, it is necessary to quickly review the specific meanings of debt and deficit.

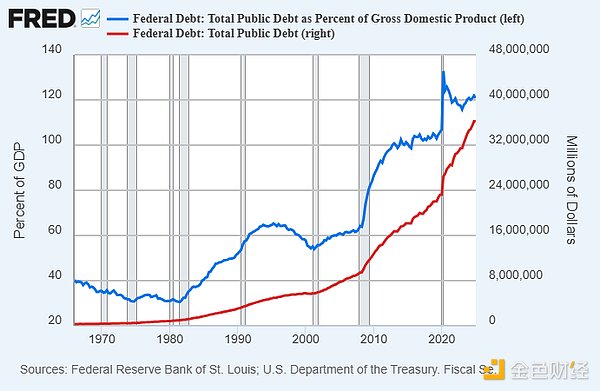

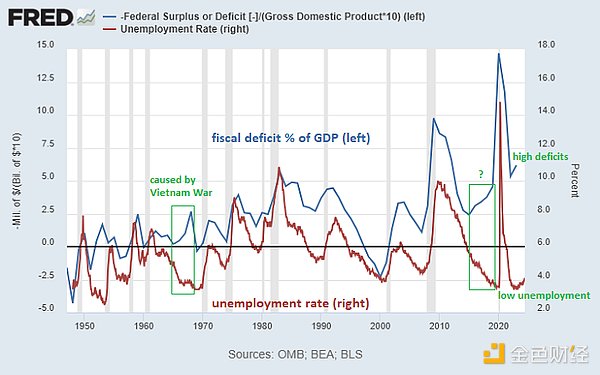

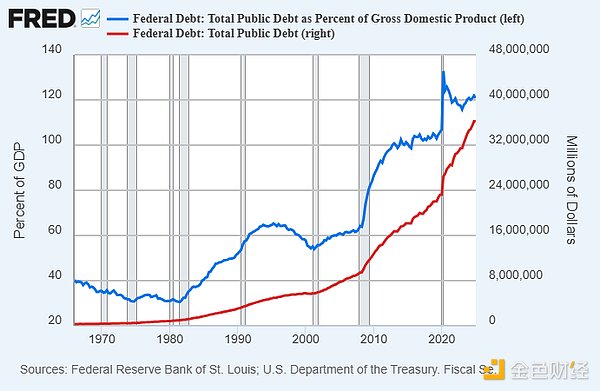

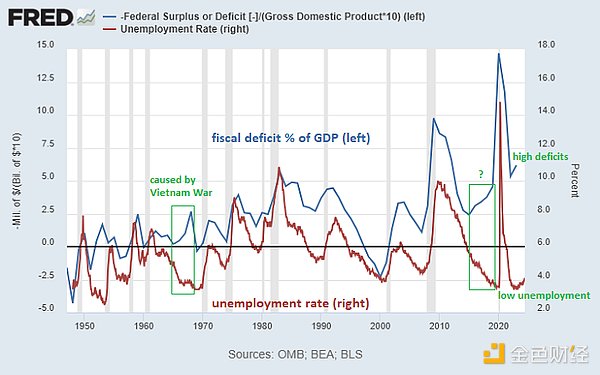

-Most years, the U.S. federal government spends more than it collects in taxes. This difference is the annual deficit. We can see the deficit over time, both in nominal terms and as a percentage of GDP: - Because the U.S. federal government has been running deficits for many years, these deficits have accumulated to form the total outstanding debt. This debt is the stock of debt owed by the U.S. federal government to creditors, and the federal government needs to pay interest. When some of the bonds mature, they issue new bonds to repay the old ones.

A few weeks ago, I gave a keynote speech at a conference in Las Vegas on the state of the US fiscal debt. This is a simple 20-minute summary of the state of the US fiscal debt.

My view, as expressed in that speech and over the years, is that the US fiscal deficit will be quite large for the foreseeable future.

Myth 1: It’s a debt we owe ourselves

A common saying popularized by Paul Krugman and others is “We owe it to ourselves.” Similar claims are often made by supporters of Modern Monetary Theory, who, for example, argue that the accumulated outstanding debt is primarily just the total surplus appropriated to the private sector.

The underlying implication is that this debt is not really a big deal. Another potential implication is that we might be able to selectively default on some of it because it is only “what we owe to ourselves.” Let’s look at each of these parts separately.

Whom it is owed to

The federal government owes money to holders of U.S. Treasury bonds. This includes foreign entities, U.S. institutions, and U.S. individuals. Of course, these entities hold a fixed amount of Treasury bonds. For example, the Japanese government is owed a lot more dollars than I am, even though we all hold Treasury bonds.

If you, me, and eight or ten other people go out to dinner together, we will all owe money at the end. If each of us eats a different amount, then the amount we owe may not be the same. Expenses usually need to be shared fairly.

In the case of the dinner above, this is actually not a big deal because the group of people at the dinner are generally friendly to each other and people are willing to generously pay for the meals of others at the dinner. But in a country of 340 million people living in 130 million different households, this is not a trivial matter. If you divide the $36 trillion federal debt by 130 million households, the total federal debt per household is $277,000. Do you think that's your share? If not, how do we calculate it?

In other words, if you have $1 million worth of Treasury bonds in your retirement account and I have $100,000 worth of Treasury bonds in my retirement account, but we are both taxpayers, then while there is a sense that "we owe it to ourselves," it is certainly not equal.

In other words, numbers and proportions do matter. Bondholders expect (usually wrongly) that their bonds will maintain their purchasing power. Taxpayers expect (again, usually wrongly) that their governments will maintain sound fundamentals for their money, taxes, and spending. This may seem obvious, but sometimes it needs to be clarified anyway.

We have a shared ledger, and we have divided authority over how that ledger is managed. Those rules may change over time, but the overall reliability of the ledger is why the world uses it.

Can we default selectively?

It is indeed possible for individuals, companies, and countries to default if they owe debts denominated in a currency that cannot be printed (such as gold ounces or other currencies) and lack sufficient cash flow or assets to repay the debts. However, developed country governments usually have debt denominated in their own currencies and can print it, so they rarely default in nominal terms. It is easier for them to print money and devalue the debt relative to their own economic output and scarce assets.

I and many others would consider a large devaluation of a currency to be a default. In this sense, the US government defaulted on bondholders in the 1930s by devaluing the dollar against gold, and then again in the 1970s by completely delinking the dollar from gold. The 2020-2021 period was also a default because the broad money supply increased by 40% in a short period of time and bondholders experienced the worst bear market in more than a century, with their purchasing power falling sharply relative to almost all other assets.

But technically, a country can default in nominal terms even if it does not have to default. Rather than subjecting all bondholders and currency holders to the pain of devaluation, it would be better to have currency holders and non-defaulting bondholders be broadly protected by defaulting only on unfriendly entities or those that can afford it. In such a tense geopolitical environment, this is a possibility that deserves serious consideration.

So the real question is: are there circumstances where the consequences of default by some entities are limited?

Some entities would have very severe and obvious consequences if they defaulted:

- If the government defaulted on its debts to retirees or asset managers that hold Treasury bonds on behalf of retirees, then this would undermine their ability to support themselves after a lifetime of work, and we would see seniors taking to the streets in protest.

- If the government defaulted on its debts to insurance companies, then this would undermine their ability to pay insurance claims, hurting American citizens in an equally bad way.

- If the government defaulted on banks, the banks would become insolvent, and consumer bank deposits would not be fully backed by assets.

Of course, most entities (the ones that survive) would refuse to buy Treasury bonds again.

The rest is a bit more attainable. Are there entities that the government could default to that would be less damaging and less existentially threatening than the above options? The odds generally lie with foreign companies and the Fed, so let’s look at each separately.

Analysis: Defaulting on Foreigners

Currently, foreign entities hold about $9 trillion in U.S. Treasuries, or about a quarter of the $36 trillion in total U.S. debt outstanding.

Of that $9 trillion, about $4 trillion is held by sovereign entities and $5 trillion by foreign private entities.

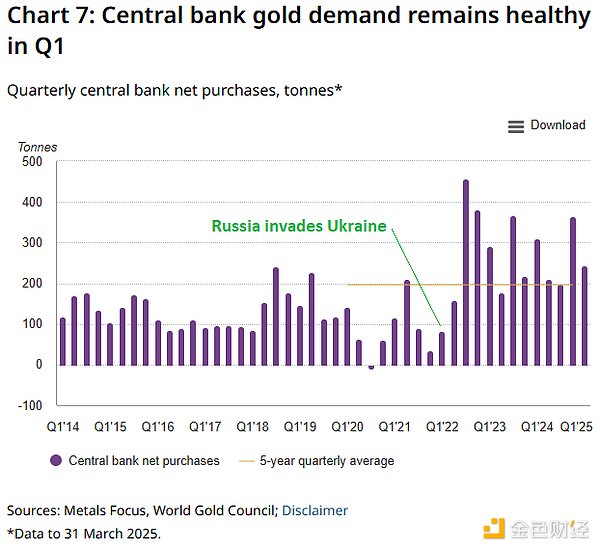

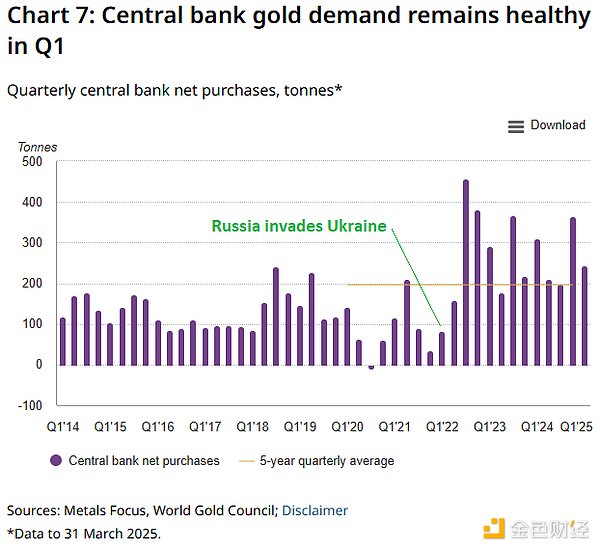

The likelihood of defaults on specific foreign entities has certainly risen dramatically in recent years. In the past, the U.S. has frozen sovereign assets in Iran and Afghanistan, but those were small and extreme cases, not enough to constitute any “real” defaults. However, after Russia invaded Ukraine in 2022, the U.S. and its allies in Europe and elsewhere froze Russian reserves totaling more than $300 billion. A freeze is not exactly the same as a default (that depends on the ultimate fate of the assets), but it’s pretty close.

Since then, foreign central banks have become sizable buyers of gold. Gold represents an asset that they can keep themselves, so it is protected from default and confiscation, and is also not prone to depreciation.

The vast majority of foreign holdings of US debt are held by friendly countries and allies. These countries include Japan, the UK, Canada, and many others. Some of these countries, such as the Cayman Islands, Luxembourg, Belgium, and Ireland, are safe havens where many institutions have set up and hold US Treasuries. Therefore, some of these foreign holders are actually US entities incorporated in these places.

China currently holds less than $800 billion in Treasuries, which is only equivalent to 5 months of US deficit spending. They are at the top of the potential "selective default" risk, and they are aware of it.

A massive default by the U.S. on such entities would greatly undermine the U.S. ability to convince foreign entities to hold its Treasuries for the long term. The freezing of Russian reserves already sent a signal, to which countries responded, but at the time they did so under the guise of a Russian “de facto invasion.” A default on debt held by non-aggressive countries would be seen as a clear default.

So overall this is not a particularly viable option, although it is not impossible in some cases.

Analysis: Fed Default

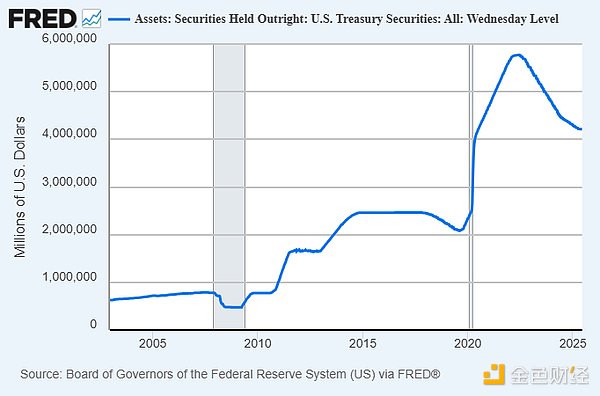

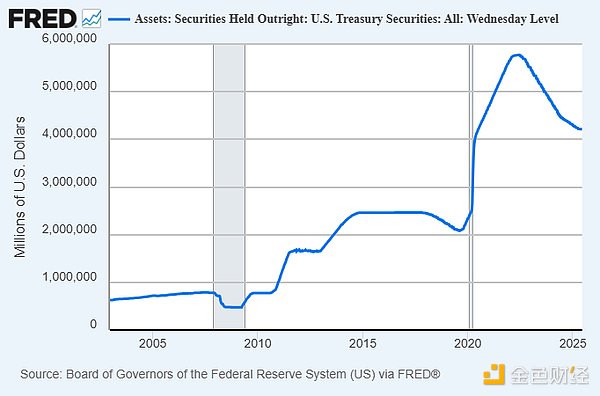

Another option is that the Treasury could default on the U.S. Treasury securities held by the Fed. Currently, the Fed holds a little over $4 trillion in U.S. Treasury securities. After all, that’s the best way to say “we owe it to ourselves,” right?

This also presents major problems.

The Fed, like any bank, has assets and liabilities. Its main liabilities are 1) physical currency and 2) bank reserves owed to commercial banks. Its main assets are 1) U.S. Treasuries and 2) mortgage-backed securities. The Fed's assets pay interest on it, and the Fed pays interest on bank reserves to set a floor on interest rates, disincentivize banks to lend, and create more broad money.

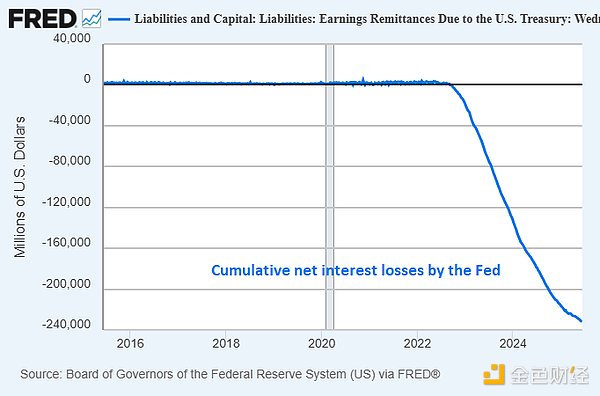

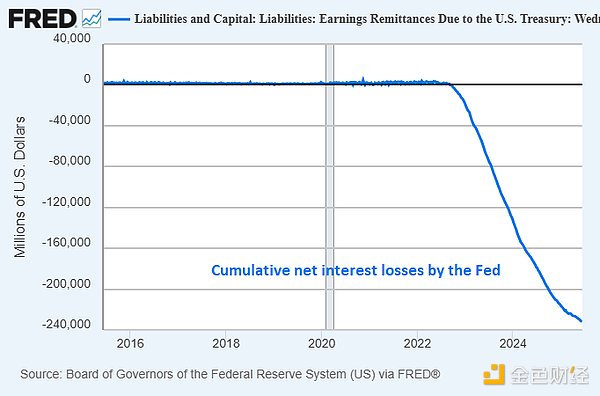

Right now, the Fed is racking up huge unrealized losses (hundreds of billions of dollars) and paying far more in interest each week than it earns. If the Fed were a normal bank, it would surely experience a run and eventually fail. But since the Fed is the central bank, no one can run on it, so it can operate at a loss for a long time. Over the past three years, the Fed has accumulated net interest losses of over $230 billion:

If the Treasury completely defaulted on its debt to the Fed, it would be severely insolvent in real terms (its liabilities would be trillions more than its assets), but as a central bank they would still be able to avoid a bank run. Their weekly net interest losses would be much larger because by then they would have lost most of their interest income (because they would only have mortgage-backed securities left).

The main problem with this approach is that it would undermine any idea of central bank independence. The central bank should be largely separate from the executive branch, so that, for example, the president cannot cut rates before an election, raise them after an election, or pull similar shenanigans. The president and Congress appoint the Fed Board of Governors and give them a long term, but from that point on, the Fed has its own budget and is generally supposed to be profitable and self-sustaining. A defaulting Fed is an unprofitable Fed with huge negative assets. Such a Fed is no longer independent, or even has the illusion of independence.

One potential way to alleviate this problem would be to eliminate the interest the Fed pays commercial banks on bank reserves. However, this interest exists for a reason. It is one of the ways the Fed sets a floor on interest rates in an environment of abundant reserves. Congress could pass legislation that: 1) forces banks to hold a certain percentage of their assets as reserves; and 2) eliminates the Fed's ability to pay commercial banks interest on these reserves. This would shift more of the problem to commercial banks.

The last option is one of the more viable avenues, and has more limited consequences. The interests of bank investors (not depositors) would be harmed, and the Fed's ability to influence interest rates and the amount of bank lending would be weakened, but it would not be an overnight disaster. Yet the Fed is only holding about two years’ worth of federal deficits, or about 12% of the total federal debt, so this somewhat extreme package of financial repression will only work as a temporary salve to ease the problem.

In short, we don’t owe ourselves debts. The federal government owes debts to specific entities, both domestic and foreign, that would suffer a host of consequential damages if they default, many of which would in turn harm the federal government and American taxpayers.

Myth 2: People have been saying this for decades

Another narrative you often hear about debt and deficits is that people have been calling them problems for decades, and things have been just fine. The implication of this view is that debt and deficits are not a big problem, and that those who think they are will ultimately just “cry wolf” prematurely over and over again, and therefore can safely be ignored.

Like many misconceptions, there is some truth here.

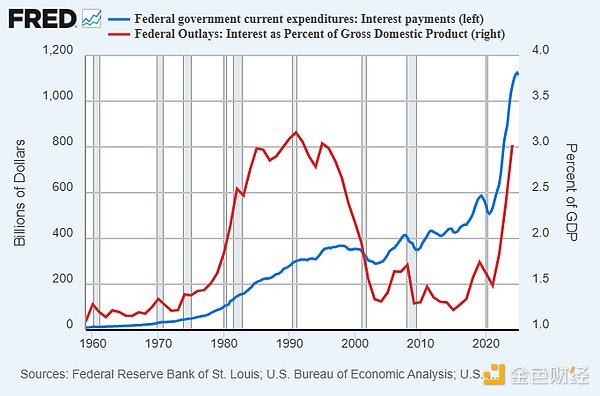

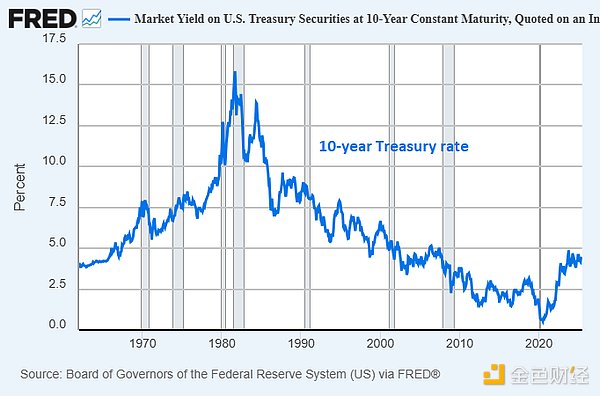

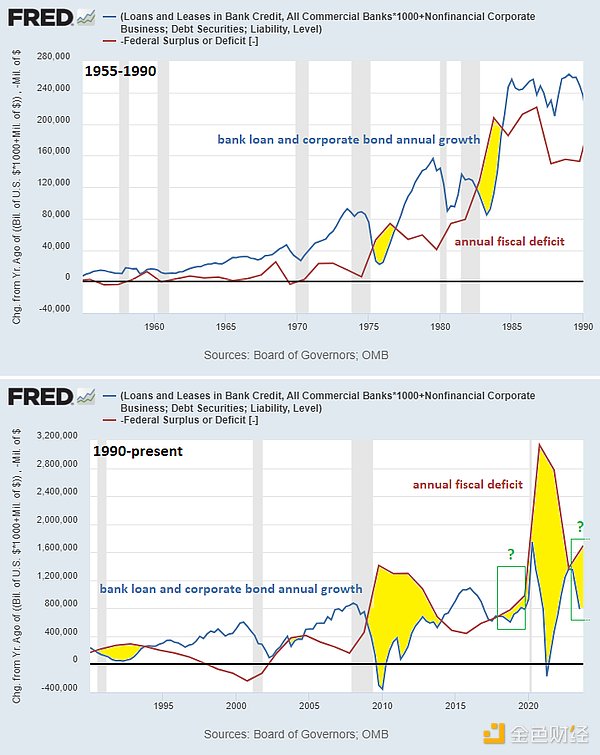

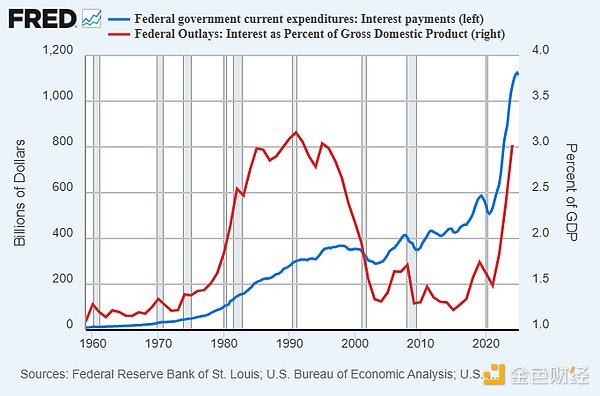

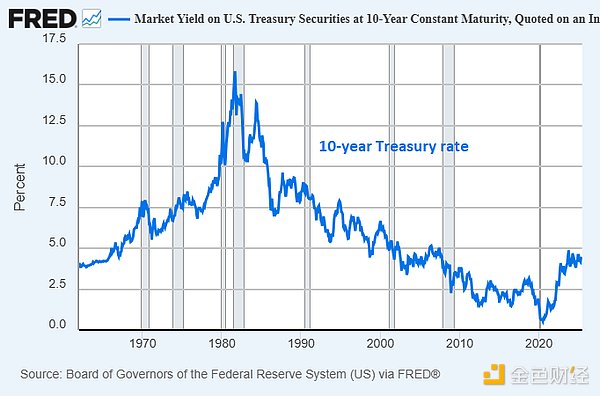

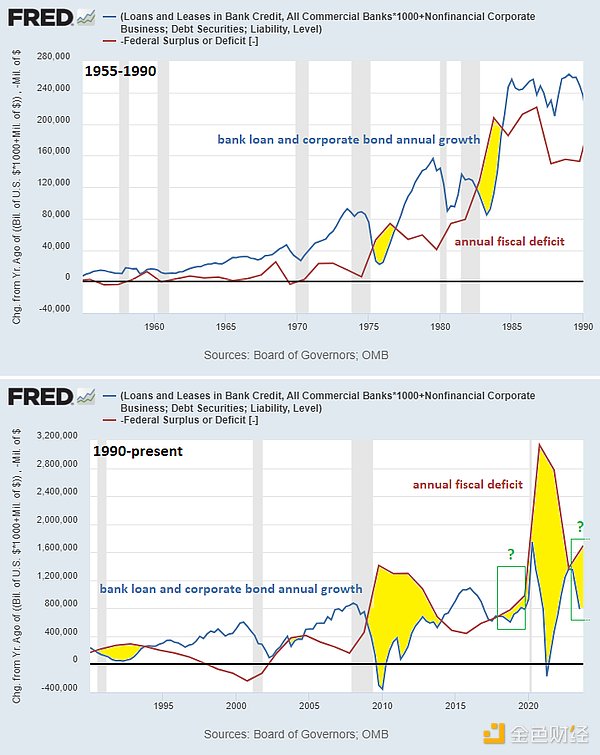

As I’ve pointed out before, the “peak of the zeitgeist” for the view that federal debt and deficits were a problem dates back to the late 1980s and early 1990s. The famous “debt clock” was erected in New York in the late 1980s, and Ross Perot’s most successful independent presidential campaign in modern history (19% of the popular vote) was largely based on the theme of debt and deficits. Interest rates were very high at the time, so interest payments as a percentage of GDP were high:

Those who thought the debt was going to get out of control were indeed wrong. For decades, things have been going pretty well. There are two main things that led to this. First, the opening up of China in the 1980s and the collapse of the Soviet Union in the early 1990s had a very significant deflationary effect on the world. Large amounts of Eastern labor and resources were able to connect with Western capital, bringing a large new supply of goods to the world. Second, partly due to these factors, interest rates were able to remain low, which made the interest payments on the growing debt stock in the 1990s, early 2000s and 2010s more manageable.

So yes, if someone said debt was a looming problem 35 years ago and is still talking about it today, I can understand why someone would choose to ignore them.

However, one should not take it too far and assume that since it didn’t matter during this time, it will never matter. This is a fallacy.

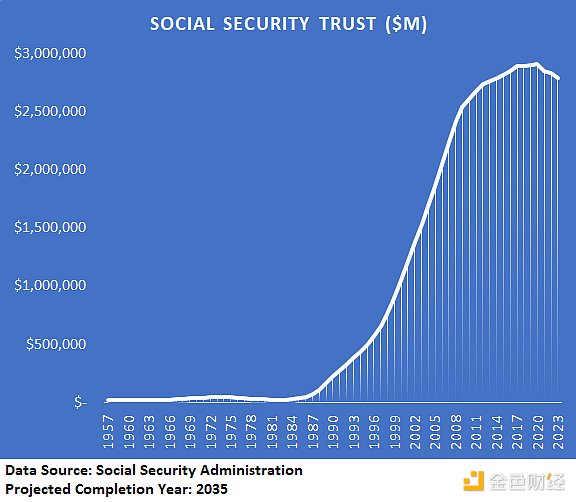

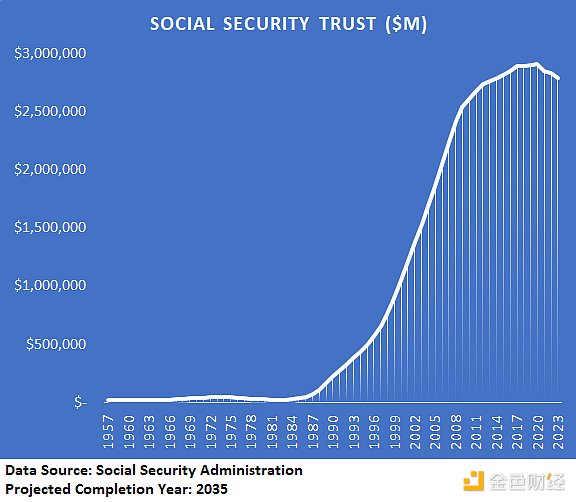

Multiple trend changes occurred in the late 2010s. Interest rates fell to zero and are no longer in a structural downward trend. The baby boomers began to retire, causing the Social Security trust to peak and enter a reduction mode, and globalization reached a potential peak, with the three-decade interconnection of Western capital with Eastern labor/resources essentially ending (and now perhaps reversing slightly).

Some trend changes are visualized as follows:

For six years, after witnessing the early stages of some of the trends, I have been emphasizing the increasing importance of fiscal spending in modern macroeconomics and investment decisions. For many years, it has been my main "North Star" as I navigated this rather chaotic macro environment.

Since these trend changes began to occur, taking debt and deficits seriously has been a good way to 1) not be surprised by some of the things that have happened and 2) manage a portfolio more successfully than a typical 60/40 stock/bond portfolio.

- My 2019 article “Are We in a Bond Bubble?” is a preface to this paper. My conclusion is that yes, we may be in a debt bubble, that the combination of fiscal spending and central bank debt monetization may be more influential and inflationary than people think, and that this situation is likely to occur in the next recession. In early 2020, I wrote “The Subtle Risk of Treasury Bonds” warning that Treasury bonds could depreciate significantly. In the 5-6 years since that article, the bond market has experienced the worst bear market in more than a century.

- At the height of the deflationary shock in March 2020, I wrote “Why This Is Different Than the Great Depression”, highlighting how massive fiscal stimulus (i.e. deficits) had begun and could get us back to nominal equity highs sooner than people thought, though it would likely come at the cost of high inflation.

Throughout the rest of 2020, I published a series of articles such as “Quantitative Easing, Modern Monetary Theory and Inflation/Deflation”, “A Century of Fiscal and Monetary Policy”, and “Banks, QE and Money Printing”, exploring why the powerful combination of fiscal stimulus and central bank support would be very different from the bank recapitalization QE of 2008/2009. In short, my argument was that this was more like the war financing of the inflationary 1940s than the private debt deleveraging of the deflationary 1930s, and therefore it would be better to hold stocks and hard money than bonds. As a bond short, I spent a lot of time debating this topic with bond longs.

By spring 2021, the stock market had risen sharply and price inflation had indeed begun to explode. This was further described and forecasted in my May 2021 newsletter, Fiscal Driven Inflation.

In 2022, as price increases peaked and the pandemic-era fiscal stimulus wore off, my thoughts on fiscal consolidation and a potential recession became quite cautious. My January 2022 newsletter, The Capital Sponge, was one of my early framings of this scenario. Much of 2022 was indeed a bad year in terms of broad asset prices and a sharp economic slowdown, but by most measures a recession was avoided because of what began to happen later in the year.

By late 2022 and especially early 2023, the fiscal deficit widened again, largely due to rapidly rising interest rates that inflated interest payments on the public debt. The Treasury General Account pulled liquidity back into the banking system, and the Treasury turned to issuing excess Treasury bills, a liquidity-friendly move designed to pull money from the reverse repo facility back into the banking system. Overall, deficit expansion is back on track. My July 2023 newsletter, titled “Fiscal Dominance,” focused on this theme.

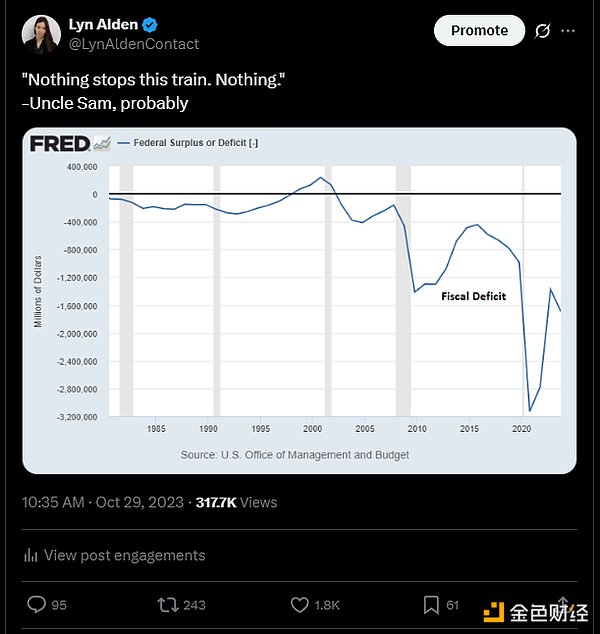

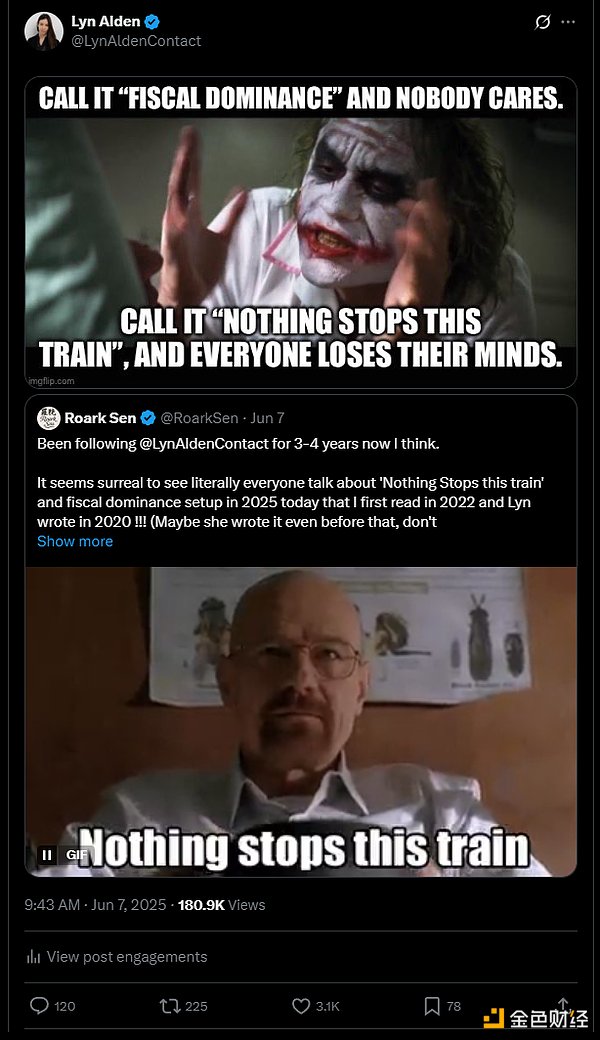

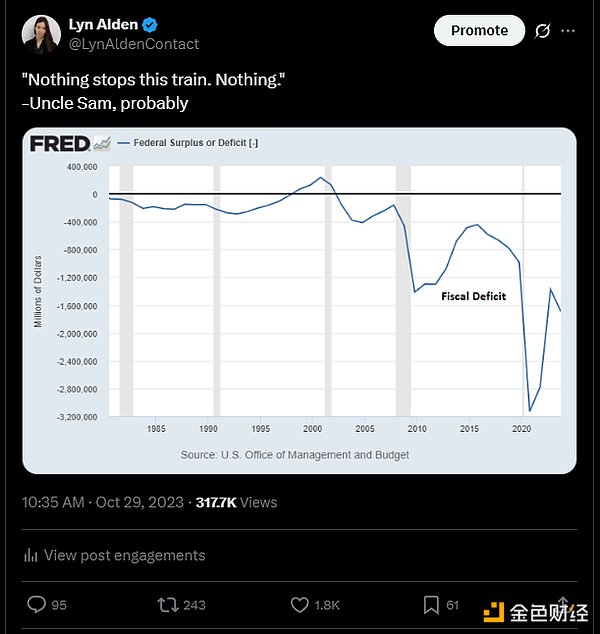

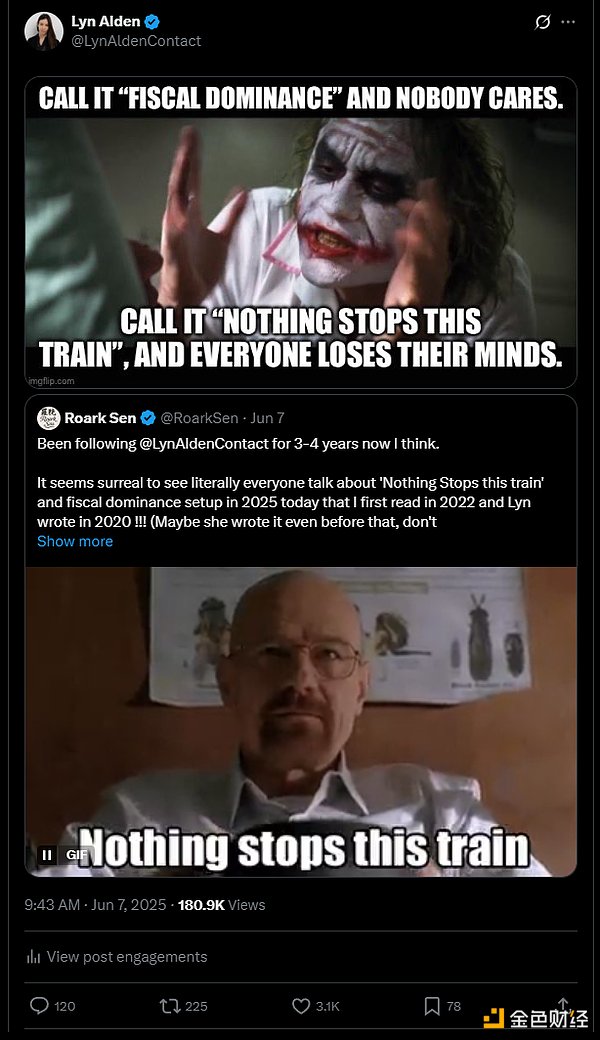

- In October 2023, the 2023 federal fiscal year (from October 2022 to September 2023) has ended, the nominal deficit has increased again, and I started the "Nothing can stop this train" meme with this theme (originally from the TV series "Breaking Bad", but here referring to the US fiscal deficit), and my tweet looked like this:

I keep emphasizing this point because it effectively expresses the main point:

My point is that we are in an era where total debt and ongoing federal deficits have real effects. Depending on whether you bear these deficits, you may feel that the effects of these deficits are positive or negative, but in any case, they have effects. These effects can be measured and reasoned about, so they have an impact on the economy and investment.

Myth 3: The Dollar Is About to Collapse

The first two myths contradict the common view that debt doesn't matter.

The third is a bit different because it refutes the view that things will blow up tomorrow, next week, next month, or next year.

Those who claim that things will blow up soon tend to fall into two camps. The first camp is people who benefit from sensationalism, click-throughs, and so on. Those in the second camp, they really misunderstand the situation. Many in the second camp do not do a deep analysis of foreign markets and therefore do not really understand the real reasons for the collapse of the sovereign bond market.

The US deficit is currently around 7% of GDP. As I have pointed out many times, this is largely structural and will be difficult to significantly reduce now or in the next decade. However, a deficit of 70% of GDP is not the problem. Size is important.

There are some important metrics to quantify here.

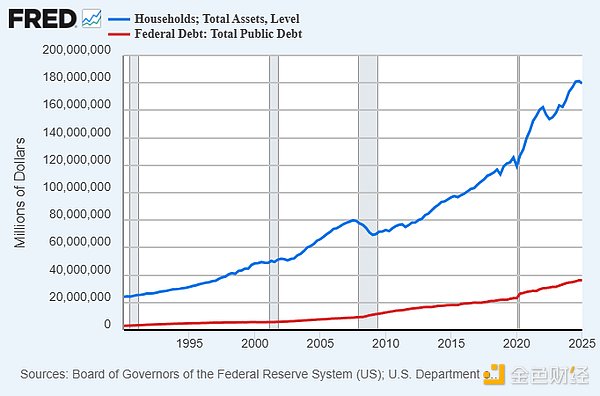

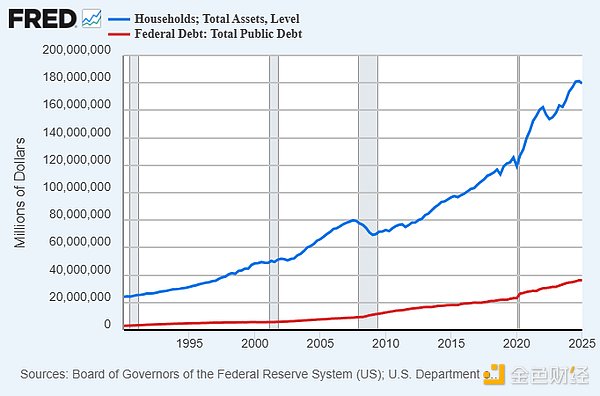

- The federal government debt is just over $36 trillion. By comparison, US households have total assets of $180 trillion, and net worth after liabilities (primarily mortgages) is $160 trillion. However, since we do not "owe ourselves", this comparison is a bit like apples and oranges, but it helps put the large numbers into a more concrete context.

The US monetary base is about $6 trillion. The total outstanding dollar-denominated loans and bonds (both public and private, domestic and international, excluding derivatives) is over $120 trillion. In the overseas sector alone, dollar-denominated debt is about $18 trillion, three times the existing base of dollars.

This means that the demand for dollars at home and abroad is extremely large and inflexible. All holders of US debt need dollars.

When countries like Turkey or Argentina have hyperinflation or near hyperinflation, the context is that almost no one needs their lira or peso. There is no deep-rooted demand for their currencies. So if their currency becomes unpopular for any reason (usually due to a rapidly growing money supply), it's easy to just negate it and send its value to hell.

This is not the case with the dollar. All of this $18 trillion of foreign debt represents an inflexible demand for dollars. Most of it is not owed to the US (the US is a net debtor nation), but foreign countries don't "owe themselves" either. Countless specific entities around the world contractually owe countless other specific entities around the world a certain amount of dollars by a certain date, and therefore need to constantly try to get dollars.

The fact that the total amount of dollars they owe exceeds the amount of base dollars in existence is crucial. Because of this, the monetary base can double, triple, or even more without causing outright hyperinflation. This is still a very small increase relative to the amount of contractual demand for dollars. When the outstanding debt far exceeds the amount of base dollars, it takes a lot of printing of base dollars to make that base dollar worthless.

In other words, people severely underestimate how much the US money supply can grow before they cause a real dollar crisis. It's not hard to create politically problematic levels of inflation or other problems, but creating a real crisis is another matter.

Think of debt and deficits as a dial, not a switch. Many people ask “when does it matter?” as if it’s a light switch that goes from no problem to disaster. But the answer is that it’s usually a dial. It matters now. We’re already running hot. The Fed’s ability to regulate the growth of total new credit has been impaired, giving it fiscal dominance. But the rest of the dial has a lot of room to turn before it actually reaches the end.

That’s why I used the phrase “nothing can stop this train.” The deficit problem is more intractable than the bulls think, which means the U.S. federal government is unlikely to get them under control anytime soon. But on the other hand, it’s not as imminent as the bears think; it’s unlikely to cause an outright dollar crisis anytime soon. It’s a long, slow train wreck. A needle is gradually turned.

Sure, we could have a mini-crisis similar to the 2022 UK Gilt crisis. Once it happens, a few hundred billion dollars can usually be devalued to put out the fire.

Suppose bond yields spike to the point where banks go bankrupt or the Treasury market becomes illiquid. The Fed could resort to quantitative easing or yield suppression. Yes, this comes at the cost of potential price inflation and has an impact on asset prices, but in this case it will not cause hyperinflation.

The dollar does face major problems in the long run. But there is nothing to suggest catastrophic problems in the short run unless we become socially and politically divided (which is not relevant to the data and therefore outside the scope of this article).

Here is some background information. Over the past decade, the U.S. broad money supply has grown by 82%. Over the same period, Egypt’s broad money supply has grown by 638%. The Egyptian pound has also outperformed the dollar by about 8 times; ten years ago, the dollar was worth just under 8 Egyptian pounds, while today it is just over 50 Egyptian pounds. Egyptians have faced double-digit price inflation for most of this decade.

I live in Egypt part of every year. It’s not easy there. They suffer from frequent energy shortages and economic stagnation. But life goes on. Even that level of currency devaluation wouldn’t be enough to send them into outright crisis, especially with an institution like the IMF on the scene, where they’re basically stuck on a path of increasing debt and devaluing currencies.

Imagine how much it would take to get the dollar into that situation, let alone worse, given how inflexible its demand is. When people think the dollar is about to collapse, I usually assume they haven’t traveled much and haven’t researched other currencies. Things are probably a lot worse than people think, but still able to partially work.

More data shows that over the past decade, China’s broad money supply has grown 145%, Brazil’s 131%, and India’s 183%.

In other words, the dollar doesn’t go directly from a developed market currency to a collapsing currency. It has to go through the “developing market syndrome” along the way. Foreign demand for dollars is likely to weaken over time. Continued budget deficits and an increasingly controlled Fed could lead to a gradual acceleration in money supply growth and financial repression. Our structural trade deficit gives us currency vulnerabilities that countries with structural trade surpluses do not have. But we start as a developed market with deep-rooted global network effects, and as things get worse, our currency is likely to resemble in many ways the currencies of developing markets. For quite a while, it will probably be more like the Brazilian currency, then the Egyptian currency, then the Turkish currency. It is not going to jump from the dollar to the Venezuelan bolivar in a year or even five years, unless something like a nuclear strike or civil war happens.

To sum up, the United States's rising debt and deficit situation is indeed having increasingly real consequences, both in the present and in the future. It is not as negligible as the "all is well" camp claims, nor is it an imminent disaster as the sensationalist camp claims. It is likely to be a thorny problem that will haunt us as a background factor for quite some time, and investors and economists must consider this if they want to make accurate judgments.

Jasper

Jasper