Author: Scott Walker, Kate Dellolio, David Sverdlov Source: a16zcrypto

Translation: Shan Ouba, Golden Finance

Registered investment advisors (RIAs) investing in crypto assets have been faced with the dual dilemma of insufficient regulatory clarity and limited viable custody options. Further complicating matters, crypto assets carry different ownership and transfer risks than the assets RIAs have historically been responsible for. RIAs’ internal teams—operations, compliance, legal, etc.—expend considerable effort to find third-party custodians willing to meet their expectations. Despite this, RIAs sometimes cannot find a custodian at all, or cannot find a custodian that can realize the full economic and governance rights of the assets, which leads RIAs to hold these assets directly. As a result, the current reality in the crypto custody space presents significant legal and operational risks and uncertainties.

The industry needs a principles-based approach to address this critical issue to serve professional investors who custody crypto assets on behalf of their clients. In response to a recent request for information from the U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC), we developed principles that, if implemented, would extend the goals of the Investment Advisers Act’s custody rules—security, regular disclosure, and independent verification—to new token asset classes.

Cryptoassets: How They Are Different

Holder control over traditional assets means that no one else has control. This is not the case with cryptoassets. Multiple entities may have access to the private keys associated with a set of cryptoassets, and multiple people may be able to transfer those cryptoassets regardless of contractual rights.

Cryptoassets also often come with a variety of inherent economic and governance rights that are fundamental to the assets. Traditional debt or equity securities can earn income (such as dividends or interest) “passively” (i.e., without the holder having to transfer the asset or take any further action after receiving it). In contrast, cryptoasset holders may need to take action to unlock certain income streams or governance rights associated with the asset. Depending on the capabilities of the third-party custodian, RIAs may need to temporarily transfer these assets out of custody to unlock these rights. For example, certain crypto assets can earn income through staking or yield farming, or have voting rights in governance proposals for protocol or network upgrades. These differences from traditional assets create new challenges for custodial crypto assets.

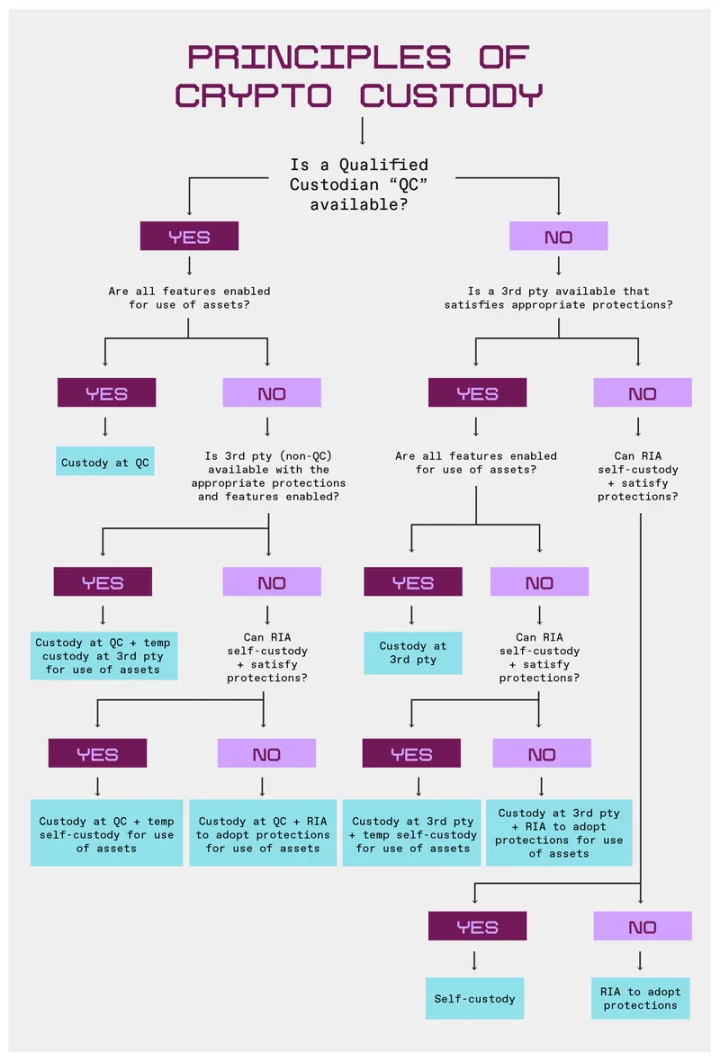

To track when self-custody is appropriate, we developed the following flow chart.

Principles

The principles we present here are designed to demystify custody for RIAs while preserving their responsibility to protect client assets. Currently, the market for qualified custodians (e.g., banks or broker-dealers) that specialize in crypto-assets is very thin; therefore, our primary focus is on the ability of a custodial entity to meet the substantive safeguards we consider necessary to custody crypto-assets—not simply the entity’s legal status as a qualified custodian under the Investment Advisers Act.

We also recommend that RIAs that are able to meet the substantive safeguards consider self-custody when third-party custody solutions that meet those substantive safeguards are unavailable or when those solutions do not support economic and governance rights.

Our goal is not to expand the scope of the custody rules beyond securities. These principles apply to crypto-assets that are securities and articulate the standards by which RIAs should exercise their fiduciary duties with respect to other asset types. RIAs should seek to maintain crypto-assets that are not securities under similar conditions and should document their custody practices for all assets, including any reasons for material differences between custody practices for different types of assets.

Principle 1: Legal Status Should Not Determine Qualification of a Crypto Custodian

Legal status and the protections associated with a particular legal status are important to a custodian’s clients, but are not the whole story when it comes to custodial crypto assets. For example, federally chartered banks and broker-dealers are subject to custody regulations that provide important protections to clients, but state-chartered trust companies and other third-party custodians may offer similar levels of protection (as we discuss further in Principle 2).

A custodian’s registration should not be the sole determinant of whether it is qualified to custody crypto-asset securities. The category of “qualified custodian” in the Custody Rule should be expanded in the crypto space to include:

State-chartered trust companies (which means they do not need to meet the criteria for the definition of “bank” in the Investment Advisers Act, but are only subject to oversight and examination by state or federal agencies with regulatory authority over banks).

Any entity registered under the (proposed) federal crypto market structure legislation.

Any other entity, regardless of its registration status, that can demonstrate that it meets strict standards for protecting customers.

Principle 2: Crypto Custodians Should Build In Appropriate Safeguards

Regardless of the specific technological tools used, crypto custodians should implement certain safeguards around the custody of crypto assets. These include:

Separation of Powers: Crypto custodians may not transfer crypto assets out of custody without the cooperation of the RIA (e.g., signing of transactions and/or device-based authentication).

Segregation: A crypto custodian shall not commingle any assets held for RIAs with any assets held for other entities. However, a registered broker-dealer may use a single omnibus wallet, provided that it maintains up-to-date records of ownership of those assets at all times and promptly discloses the fact of such commingling to the relevant RIAs.

Source of Custody Hardware: A crypto custodian shall not use any custodial hardware or other tools that increase security risks or present a risk of compromise.

Audit: A crypto custodian shall undergo financial control and technical audits at least annually. Such audits should include:

ISO 27001 certification;

penetration testing (“pen testing”); and

testing of disaster recovery procedures and business continuity plans.

Service Organization Controls (SOC) 1 Audit;

SOC 2 Audit; and

Recognition, measurement, and presentation of crypto assets from the holder’s perspective;

Financial controls audit conducted by an auditor registered with the Public Company Accounting Oversight Board (PCAOB):

Technical Audit:

Insurance: Crypto custodians should have adequate insurance coverage (including “umbrella” insurance) or, if that is not available, establish adequate reserves, or a combination of the two.

Disclosures: Crypto custodians must provide RIAs with a list of the principal risks associated with their custody of crypto assets, and the relevant written supervisory procedures and internal controls to mitigate those risks, on an annual basis. Crypto custodians will evaluate this on a quarterly basis and determine whether updated disclosures are required.

Custody Locations: A crypto custodian should not custody crypto assets in a location where local law would require that such custody assets become part of the bankruptcy estate in the event of the custodian’s bankruptcy.

In addition, we recommend that crypto custodians implement safeguards related to the following processes at each stage:

Preparation Phase: Review and evaluate the crypto assets to be custodyed – including the key generation process and transaction signing procedures, whether they are supported by open source wallets or software, and the source of each piece of hardware and software used in the key management process.

Key Generation: All levels of this process should use encryption, and multiple encryption keys should be required to generate one or more private keys. The key generation process should be both "horizontal" (i.e., multiple encryption key holders at the same level) and "vertical" (i.e., multiple encryption levels). Finally, arbitration requirements should also require the physical presence of validators, which should be protected and monitored to prevent interference.

Key Storage: Keys should never be stored in plain text, only in encrypted form. Keys must be physically separated by geographic location or by individuals with different access rights. If a hardware security module (or similar module) is used to maintain key copies, it must meet the U.S. Federal Information Processing Standard ("FIPS") security rating. Strict physical separation and authorization measures should be in place to ensure air-gap isolation. (See our full response for example measures). Crypto custodians should maintain redundancy of at least two layers of encryption to enable operations to be maintained in the event of a natural disaster, power outage, or property damage.

Key Usage: Wallets should require identity verification; in other words, they should verify that the user is who they claim to be, and that only authorized parties can access the contents of the wallet. (See our full response for example identity verification forms). Wallets should use mature, open-source cryptographic libraries. Another best practice is to avoid using a single key for multiple purposes. For example, encryption and signing should use different keys. This follows the “principle of least privilege” to prevent compromise, meaning that access to any asset, information, or operation should be limited to parties or code that absolutely requires the system to operate.

Principle 3: Crypto Custody Rules Should Allow RIAs to Exercise Economic or Governance Rights Related to the Crypto Assets They Custody

Unless otherwise directed by a client, RIAs should be able to exercise economic or governance rights related to the crypto assets they custody. Under the previous SEC administration, given the uncertainty surrounding token classification, many RIAs took a conservative approach by placing all of their crypto assets in custody with a qualified custodian (unless no qualified custodian is available). As we mentioned previously, the market for alternative custodians is limited, which often results in only one qualified custodian willing to support a particular asset.

In these cases, the RIA may request that it be allowed to exercise economic or governance rights, but the crypto custodian may choose not to provide these rights based on its internal resources or other factors. In turn, the RIA does not consider itself entitled to choose another third-party custodian or engage in self-custody to exercise these rights. Examples of these economic and governance rights include staking, yield farming, or voting.

In accordance with this principle, we believe that RIAs should select third-party crypto custodians that meet relevant safeguards that allow the RIA to exercise its economic or governance rights associated with the crypto assets it holds. If the third party cannot meet both requirements, then the RIA's temporary transfer of assets to self-custody to exercise economic or governance rights should not be considered a transfer out of custody - even if the assets are deployed to any non-custodial protocol or smart contract.

All third-party custodians should make best efforts to provide RIAs with the ability to exercise these rights while the assets remain with the custodian and, with the RIA’s authorization, should be permitted to take commercially reasonable actions that may be necessary to enforce any rights associated with on-chain assets. This includes the right to expressly delegate any crypto asset to the RIA’s wallet to exercise any rights associated with that asset.

Before removing any crypto asset from custody to exercise rights associated with that asset, the RIA or custodian, as the case may be, must first reasonably determine in writing whether those rights can be exercised without removing the asset from custody.

Principle 4: Crypto Custody Rules Should Be Flexible to Allow for Best Execution

RIAs have an obligation of best execution with respect to traded assets. To this end, regardless of the status of the asset or custodian, an RIA may transfer an asset to a crypto trading platform to ensure best execution for that asset, provided that the RIA has taken the necessary steps to ensure the resiliency and security of the trading venue, or that the RIA has transferred the crypto asset to an entity regulated under crypto market structure legislation once the relevant legislation is finalized.

The transfer of crypto assets to a trading venue shall not be considered a withdrawal of custody if the RIA determines that it is advisable to transfer the crypto asset to such venue in order to obtain best execution. This would require the RIA to reasonably determine that the venue is suitable for best execution. If the transaction cannot be properly executed on that venue, the assets should be promptly returned to the crypto custodian for custody.

Principle 5: RIAs Should Be Permitted to Self-custody in Certain Circumstances

While the use of a third-party custodian should remain the primary option for crypto-assets, RIAs should be permitted to self-custody crypto-assets in the following circumstances:

The RIA determines that there is no third-party custodian that can custody the crypto-assets that meets the protections required by the RIA.

The RIA’s own custody arrangement provides at least as much protection for the crypto-assets as a reasonably available third-party custodian.

Self-custody is necessary to best exercise any economic or governance rights associated with the crypto-assets.

When an RIA decides to self-custody crypto assets for one of the reasons listed above, the RIA must confirm annually that the circumstances justifying self-custody remain the same, disclose the self-custody to clients, and subject such crypto assets to the Custody Rule’s audit requirements, where auditors can confirm that the assets are segregated from the RIA’s other assets and adequately safeguarded.

A principles-based approach to crypto custody ensures that RIAs can fulfill their fiduciary responsibilities while accommodating the unique characteristics of crypto assets. By focusing on substantive protections rather than rigid classifications, these principles provide a pragmatic path to safeguard client assets and unlock asset functionality. As the regulatory environment evolves, clear standards rooted in these protections will enable RIAs to responsibly manage crypto investments.

Aaron

Aaron

Aaron

Aaron Davin

Davin Davin

Davin Brian

Brian Hui Xin

Hui Xin Jasper

Jasper Davin

Davin Aaron

Aaron Joy

Joy Hui Xin

Hui Xin