Co-Conspirator in OneCoin Crypto Scam Faces Four Years Behind Bars

After the crackdown on the OneCoin scam, the former in-house legal counsel, Irina Dilkinska, has been sentenced to four years in jail.

Kikyo

Kikyo

Author: Deng Jianpeng, Professor and Doctoral Supervisor of the School of Law, Central University of Finance and Economics. Li Ang, Graduate Student of the School of Law, Central University of Finance and Economics. The original article was published in the Hebei Journal, Issue 2, 2025.

With the maturity and application promotion of blockchain technology, the development of decentralized digital economy represented by crypto assets such as Bitcoin is in full swing, stimulating the global tax system to respond. However, China's tax law system and practice have shown an evasive attitude towards crypto assets as a potential tax source. Difficulties such as unclear taxability and lack of taxation paths hinder the development of practice. The tax department can reconstruct the taxability theory through the path of legal functionalism, provide a source of legitimacy with normative documents and the principle of tax legality, support the rationality with differentiated institutional needs, and use the taxation scheme of income measurement tax base as the basis for feasibility. Further, through the binary distinction between acquisition and circulation links, the taxable object type, tax items and other tax law elements of homogeneous and non-homogeneous crypto assets are specifically analyzed, and crypto assets are included in the current VAT and income tax governance framework.

[Keywords]Crypto assets; digital economy; tax governance; tax law; Bitcoin

The contemporary information technology revolution has profoundly shaped the production, lifestyle, property form and even value concept of human society. Among them, blockchain is a major technological innovation in the transformation from centralized information Internet to decentralized value Internet. One of the ways in which blockchain technology affects the economy is to promote economic change with the help of crypto-asset development. From the evolution law of technology-economy-tax system, the new economic form is driven by technological innovation and ultimately drives the tax system to adapt to the new economic form. From a global perspective, in the "two-pillar" international tax plan led by the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (hereinafter referred to as "OECD"), the OECD clearly realizes that crypto assets will have a profound impact on global tax decision-making departments. Based on the profound impact of crypto assets on tax practices, tax departments of various governments have actively explored. The United States regards crypto assets as property and imposes income tax and capital gains tax, and is expected to improve the corresponding regulatory framework in the future; the United Kingdom assesses the tax treatment of crypto assets based on specific circumstances, and has tried to treat crypto asset transactions as "gambling" and impose high tax rates; Canada and Australia also regard them as assets or commodities and impose taxes. China's Central Economic Work Conference held in December 2023 proposed to "plan a new round of fiscal and tax system reform." At the same time, China's "14th Five-Year Plan" and the "Guiding Opinions on Accelerating the Promotion of Blockchain Technology Application and Industrial Development" jointly issued by the Ministry of Industry and Information Technology clearly emphasize the need to "vigorously develop the blockchain economy." It can be seen that in the face of the world wave of crypto assets based on blockchain technology, China's top-level design and policy tone have gradually become more open and inclusive. Crypto assets bring challenges to China's fiscal and taxation system, and may also provide opportunities for China's fiscal and taxation system reform. Some scholars pointed out that the challenges are mainly reflected in three aspects: first, the buying and selling prices of crypto assets often show high volatility in the short term, and it is difficult to confirm tax obligations based on this; second, it is difficult to trace the source of tax; third, it challenges the legal basis and governance framework of the traditional tax system.

As far as the research in the field of Chinese tax law is concerned, there are generally two different conceptual paths for the tax law governance of "crypto assets": first, dig deep into the economic essence and legal attributes of "crypto assets", analyze the similarities and differences between different types of crypto assets, and incorporate them into the existing tax law system; second, build an independent "digital tax system" outside the existing tax law system that serves the digital economy and metaverse economy. At the moment when the digital tax 1.0 era with digital platform economy as the core is changing to the digital tax 2.0 era with crypto assets as one of the cores, how to properly regulate crypto assets, a potential tax source of the future digital tax system, is undoubtedly a proposition that needs to be responded to in building a new era of national tax system. Therefore, how to use the existing tax law theory and taxation system to break the dilemma of "taxability" of crypto assets and include crypto assets in the scope of China's tax sources is a more forward-looking and urgent issue. The global market value of crypto assets has exceeded 2 trillion US dollars. What is disproportionate to the huge market size is that domestic taxation pays less attention to it. Tax law plays a macro-control function. It is necessary to intervene in the crypto asset market and guide market players to participate in an orderly manner. The above situation highlights the importance of research on crypto-asset taxation. Tax law scholars are urgently needed to respond to the characterization, taxability and specific tax treatment of crypto-assets to ensure national tax interests and safeguard national economic security.

Unfortunately, on the one hand, current domestic tax practices and judicial practices often take a negative and evasive attitude towards practical issues involving crypto-assets, causing crypto-assets that actually participate in the economic market and investment market to be outside the tax law framework, resulting in institutional problems of tax source loss; on the other hand, research on the tax source governance of crypto-assets in the field of tax law is in the ascendant, but not sufficient. Against this background, this article, based on the clarification of the legal nature of crypto-assets, explores the taxation path for incorporating crypto-assets into the scope of China's tax source governance through the tax law path of taxability proof, and makes a contribution to the construction of its tax law governance system.

Theoretical research begins with the ups and downs of practice, either to break down obstacles and draw up a blueprint for the rise of a certain practice, or to analyze and explore the causes of the decline of a certain practice. As to whether crypto assets can be integrated into the current tax law framework, we should go back to the current tax practice of crypto assets to explore the crux of its practice. Existing research has different opinions on the use of concepts such as "cryptocurrency", "encrypted digital currency", "virtual currency" and "virtual assets". Based on this, it is necessary to first summarize various concepts in a pertinent way, refine legal expressions that are more in line with the theme of the article, and anchor the research object and scope.

(I) The concept of crypto assets and the determination of their tax attributes

The use of the name of crypto assets has significant stage characteristics. Bitcoin became the only representative of crypto assets at the beginning of its birth. At that time, expressions such as "virtual currency" and "cryptocurrency" were more common. With the birth of Ethereum in 2014, a large number of tokens with investment and utility functions gradually became the mainstream of crypto assets, and expressions such as "virtual assets" and "digital assets" began to appear frequently. In this regard, the OECD, as a core organization for promoting international tax exchanges and cooperation, tends to use the expression "crypto assets" and defines them as "relying on cryptography and distributed accounting methods, especially blockchain technology" and "without relying on traditional financial intermediaries and central managers, and achieving issuance, recording, transfer or storage in a decentralized manner". It can be specifically divided into payment exchange tokens, utility tokens and security tokens. The OECD definition emphasizes its "asset" attributes, accurately grasps its characteristics such as decentralization and disintermediation, and gathers international consensus. It is a relatively accurate definition of crypto assets at this stage. At the same time, the tax law nature of crypto assets should also be clarified to clear obstacles for further solving the problem of the taxability of crypto assets. The taxable object of tax law is the legal fact that has economic significance and can represent the tax-bearing capacity of the taxpayer formed by citizens or enterprises in the order of citizens' lives. This determines that the tax law itself is in the "downstream area" of the legal system, and its dependence on civil law is relatively obvious. Many tax law provisions are established on the basis of civil law. Therefore, before launching a qualitative analysis of crypto asset tax law, it is necessary to sort out and summarize the research conclusions in the field of civil and commercial law.

There are differences in the definition of the nature of crypto assets in the field of civil and commercial law, but most believe that crypto assets have property attributes: the property right theory and the data theory advocate; the creditor's rights theory recognizes the impact of crypto assets on real economic value and recognizes that it represents economic interests in real life; the securities theory recognizes that it meets the conditions. It can be seen that the property attributes of crypto assets have been widely confirmed in the field of civil and commercial law. In the perspective of tax law theory, whether crypto assets have property attributes is also an unavoidable issue-as the taxability theory of the basic theory of tax law, its primary premise is "economic taxability", so it is necessary to demonstrate the attributes of crypto assets in the perspective of tax law.

Crypto assets with blockchain as the underlying technology naturally have value attributes. On the one hand, the issuance of crypto assets is the continuous production of new blocks. The generation of each new block requires proof of work or other consensus mechanisms to prove that the production of new crypto assets requires real costs. Taking the issuance of Bitcoin as an example, in real life, it is mostly manifested in high electricity resource costs, computing equipment cost investment and maintenance costs, which means that the issuance process of crypto assets condenses indiscriminate human labor. On the other hand, in recent years, crypto assets have been sought after by the market because they have become the "outlet" of capital seeking profits. The rising prices have attracted more potential "miners" to join the market and participate in the "mining" competition, resulting in an increase in the computing power required to produce new blocks, an increase in the cost of obtaining rewards, and an increase in the difficulty of "mining". It can be seen that the cost of issuing crypto assets usually rises with the rise in the market price of crypto assets, that is, there is a corresponding relationship between the price and cost of crypto assets. The original positioning of the invention of crypto assets was a highly secure distributed "ledger", and the blocks recorded information on Internet transactions (such as Bitcoin payments). Because transaction information is extremely valuable to the development of the digital economy, all sectors of society are actively exploring "account books" that can effectively, safely and permanently preserve this information. In other words, "value" itself is the connotation of crypto assets. In summary, crypto assets are undoubtedly a new type of value carrier in the pure economic sense, with irrefutable property attributes.

"Tax law norms study the relationship between people, that is, the distribution relationship between people." To prove the property attributes of crypto assets from the perspective of tax law, it is also necessary to think about its relationship with people. In other words, the core of identifying the property attributes of crypto assets from the perspective of tax law lies in its "gain" to taxpayers, not just "profitability" in the economic sense. From an economic perspective, as long as there is profit, taxes can be paid. But from a legal perspective, the core of taxation is not to "draw" from economic growth, but to achieve the purpose of guiding people's behavior by regulating the distribution of rights and interests of parties and subject matters in legal relationships. It can be seen from this that whether the property attributes of crypto assets can be recognized by tax laws depends on whether the value "gain" it has can be actually enjoyed by potential taxpayers. The measurement basis of tax collection and management is closely related to accounting measurement. The above-mentioned proof of the "profitability" of crypto assets is consistent with the definition of "assets" in accounting standards. Therefore, whether crypto assets have "profitability" in tax law can be measured by referring to the accounting element confirmation rules for assets in accounting, that is, by the standard of "economic benefits are likely to flow into the subject and economic benefits can be reliably measured". On the one hand, crypto assets themselves have the "possessable" characteristics, which means that the corresponding relationship between crypto assets and their holders is extremely close. Therefore, there are almost no external obstacles in the process of transmitting the economic benefits of crypto assets to holders, which meets the "inflow" standard; on the other hand, although crypto assets are strictly prohibited from circulating as legal tender or conducting related exchange business in China, and their own price volatility is large, and even the price of the same crypto asset may be different in different scenarios, this does not prevent the price of crypto assets from being "reliably measured". Similar to traditional accounting assets such as financial assets, their price measurement and value discovery rely on the role of relevant markets. If the market is relatively effective, crypto assets can obtain measurement basis from the market. The trading market of crypto assets has reached a stable scale and is on an upward trend. There are many global market participants and the upstream and downstream industries related to it are complete. It should be considered that an effective market has been formed. Therefore, crypto assets meet the element recognition standards under the tax law framework and their property attributes should be recognized.

In summary, crypto assets show property attributes both in the traditional civil and commercial law field and in the tax law field. The parties holding, receiving or transferring crypto assets should be able to represent the parties' tax-bearing capacity and changes.

(II) Dilemma in tax practice

From the perspective of policy orientation, China's financial regulatory authorities have long been vigilant about crypto asset transactions. The "Notice on Preventing Bitcoin Risks" jointly issued by five ministries and commissions in 2013 (hereinafter referred to as the "2013 Notice") and the "Announcement on Preventing Token Issuance and Financing Risks" jointly issued by six ministries and commissions in 2017 (hereinafter referred to as the "2017 Announcement") deny the use and circulation of crypto assets as currency, and clearly state that ICO (initial token offering) is suspected of illegal issuance of securities or illegal fundraising. The Notice on Further Preventing and Dealing with the Risks of Speculation in Virtual Currency Transactions (hereinafter referred to as the "2021 Notice") jointly issued by ten ministries in 2021 once again emphasizes that virtual currencies represented by Bitcoin are not legal tender and cannot be circulated and used as currency in the market. On the other hand, it prohibits financial exchange businesses involving virtual currencies, and investors in investment-related financial businesses are at their own risk. Although Bitcoin is only one type of crypto assets, as the blockchain application with the highest popularity and capital activity in the crypto asset market, it has become the representative of crypto assets. Strict and prudent decision-making may be a choice that suits the current national conditions. One of the reasons is that the Bitcoin market is full of speculative transactions. Bitcoin prices fluctuate violently, so investing in Bitcoin will face huge risks, and there is a possibility that individual risks will be transmitted to the group. In addition, Bitcoin is outside the existing financial regulatory framework in China, posing a certain threat to the foreign exchange management system and is easily used for illegal and criminal activities such as money laundering or drug trafficking. However, the negative evaluation of crypto assets at the policy level has led to an unavoidable problem for China's tax law system: whether to tax crypto assets (creation, holding, trading or appreciation)? Will this make the tax law conflict with the current regulatory policy? In other words, whether crypto assets are taxable within the current tax law framework is an unavoidable and urgent issue in the field of tax law. The following are the responses of provincial tax authorities in some key tax cities to the consultation on crypto asset tax issues:

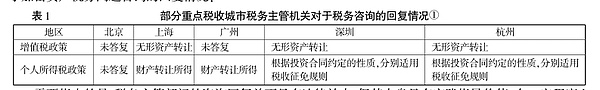

It should be pointed out that the consultation response of the tax authorities does not have legal effect, but it itself has practical guidance value, and to a certain extent reflects the cognition and consideration of different tax authorities on crypto assets. As can be seen from Table 1, most tax authorities have not yet reached a conclusion on whether to tax crypto assets and how to tax them. There are obvious differences of opinion between tax authorities in different regions, and most regions, including economically developed first-tier cities such as Beijing, Shanghai, Guangzhou and Shenzhen, lack taxation practices on crypto assets.

The rules for tax treatment of crypto assets are still unclear. In summary, the tax treatment opinions on crypto assets are mainly concentrated in the fields of value-added tax and personal income tax, including the treatment conclusions of intangible asset transfer and property transfer income. Most regions did not directly give the treatment conclusions, but only cautiously stated that the nature of the current "Bitcoin" tax law is unclear, there is no official guidance, and the relevant transaction behavior needs to be analyzed according to the specific situation.

Overall, there is a negative tendency in the field of tax practice on the taxability of crypto assets. At present, the tax authorities have unclear cognition and attitude on the issue of "whether crypto assets can be taxed", and have not formed a unified practical cognition on the taxability of crypto assets. There is no clear path on the issue of "how to tax crypto assets", which has aggravated the conservative tendency of taxation practice. These practical difficulties are in sharp contrast to the research and exploration in the theoretical community. Taxation theory researchers represented by the Institute of Tax Science of the State Administration of Taxation are actively exploring the taxation of crypto assets. It can be seen that the current negative tax practice in the field of crypto assets does not mean that taxation will inevitably be abandoned in the future. In addition, China insists on conducting research on the taxation theory of crypto assets, and even encourages the academic community to conduct relevant special seminars, conveying the future possibility of taxation of crypto assets. At present, there is a general negative tendency in the practice of this field. There are two main reasons: First, the complexity of the underlying technical structure of crypto assets makes it difficult for tax staff with a liberal arts background to learn and understand the essence of crypto assets and put forward practical tax treatment suggestions. This is more prominent at the moment when the types and forms of crypto assets are changing with each passing day; second, there is a trend of crypto assets being completely denied in financial regulatory policies. Although the aforementioned documents are not high in the level of legal effectiveness, they have a huge impact. Therefore, it is more necessary to conduct theoretical research on the taxability of crypto assets. Only by clarifying the tax law attributes of crypto assets and responding to the tax law positioning of crypto assets can we achieve a "breakthrough" in the dilemma of tax practice.

The purpose of tax law is to tax economically significant behaviors or results in economic production and life, so as to raise fiscal funds to support the state in providing public functions that general entities cannot, must not or are unwilling to perform. Its legitimacy stems from the protection of the exercise of the state's public service functions. The purpose of tax law can be used to derive the general argumentation idea of taxability: the taxable object has economic significance (usually manifested as non-public welfare benefits), and the parties obtain benefits based on this and increase their tax burden capacity due to the benefits, which is deemed to meet the basic conditions of taxability. Therefore, the widely recognized property attributes of crypto assets in the field of civil and commercial law prove that it is very likely to generate benefits that conform to the general concept of the economic society in the transaction and circulation links, and such benefits are generally not of public welfare, reflecting the increase in the tax burden capacity of the parties, so crypto asset transactions are taxable. At this point, the proof of taxation of crypto assets seems to have been completed, but the above-mentioned syllogistic proof method is easy to fall into the logical rut of "the major premise is false" and draw a wrong conclusion. At present, there is no unified consensus on the taxability theory in the academic community, but a few basic theories of "practical superiority", which means that the taxability theory itself may be wrong, so the above-mentioned argument is actually a "non-normative" syllogism. Even so, such an inference process still has certain value and can provide a demonstration guide for thinking about the question of "whether crypto assets are taxable". The current task of taxability research is to think about how to make up for the possible fallacy of the "major premise" and make the syllogism perfect.

In this regard, we can refer to the functionalist legal hermeneutics thinking, compare the actual needs that the tax law wants to achieve, examine the structure of the taxability theory, and carry out the proof on this basis. The essence of the traditional taxability theory is "the 'legitimacy' of taxation". In the field of law, "legitimacy" is usually understood as "legality" and "rationality", and less attention is paid to "feasibility". However, the taxability of crypto assets, as a tax system evolution issue caused by a new round of iteration of production factors, is different from traditional tax sources such as tangible property or capital, which are easy to price. It has its own problems such as changeable forms and high technical barriers to taxation and management. Therefore, it is necessary to include "feasibility" in the scope of taxability proof, which is discussed in detail as follows.

(I) Legitimacy of taxation of crypto assets

The legal system cannot provide a legitimacy basis for itself and needs external justifications to support it. Taxation is a legal "invasion" of taxpayers' property, and the importance of its legitimacy is self-evident. China implements a relatively conservative and strict policy orientation for crypto assets, and the attitude of judicial judgments tends to be negative. In this case, "legitimacy" is intended to explore whether there is formal space for taxation of crypto assets in the current legal system, mainly including the legitimacy of crypto asset transactions and the legitimacy of taxation of crypto asset transactions.

There is currently no clear legal provision on the legitimacy of crypto asset transactions, and it is necessary to determine whether there is a basis in the "non-legal" level of normative documents to support the "legitimacy" of taxation of crypto assets. The regulatory documents that regulate crypto assets include the aforementioned 2013 Notice and 2017 Announcement. A detailed study of their contents reveals that the Notice and Announcement set two major restrictions on the "prohibition" provisions: First, in terms of applicable subjects, the above documents mainly prohibit "financial institutions and payment institutions" from participating in "bitcoin transactions". This means that individuals and organizations other than payment institutions represented by banks and other non-bank payment institutions, whether directly or indirectly involved in "bitcoin transactions", are not affected by the provisions of the preceding paragraph. Secondly, in terms of the objects targeted, the two regulatory documents directly specify the "bitcoin" as a single type of crypto asset, and do not cover other types of crypto assets. In other words, the two regulatory documents essentially deny the payment function of crypto assets in China. As for the value carrier function of crypto assets, such as NFT becoming a recognized digital artwork by recording specific data, it is not within the scope of their regulations. Therefore, if the above clauses are understood as "prohibiting all crypto asset transactions", it has exceeded the scope of their document effectiveness. In addition, the two documents retain the "legality" space for crypto asset transactions to a certain extent. Article 4 of the 2013 Notice stipulates: "Internet sites that provide services such as Bitcoin registration and trading should earnestly fulfill their anti-money laundering obligations, identify users, and require users to register with real names, register their names, ID numbers and other information." If "not providing Bitcoin trading services to customers" is understood as a total ban or an absolute ban, then why is it necessary to explicitly stipulate in Article 4 that Bitcoin registration and trading platforms need to "earnestly fulfill their anti-money laundering obligations"? If the policy attitude of a total ban is strictly followed, then all platforms involving "Bitcoin trading services" should be directly banned or prohibited for suspected violations of the law, and there is no room for fulfilling anti-money laundering obligations. Therefore, there is only one reasonable explanation - the 2013 Notice only prohibits Bitcoin from circulating in the market as a currency, and does not prohibit individuals or institutions from holding it as a "specific virtual commodity" at their own risk. Therefore, the legal and compliant status of crypto asset trading platforms can still be recognized at that time on the premise of meeting anti-money laundering obligations.

In addition to refining the contents of the above-mentioned documents, the 2021 Notice explicitly defines crypto-asset-related business activities as illegal financial activities, which means that for transaction service providers, their extraterritorial legal space is banned. However, the 2021 Notice does not mention the characterization and treatment of non-operational transactions at the risk of individuals. In other words, there is currently no administrative regulation that explicitly denies individuals holding, trading, or even investing in crypto assets. Previously, the Supreme Court issued Guiding Case No. 199, revoking the arbitration award that previously confirmed that Bitcoin has property attributes, can be denominated in RMB, and is protected by law on the grounds of violating national financial regulatory regulations and violating social public interests. However, in fact, the judgment is a misreading and misuse of normative documents such as the 2013 Notice. The aforementioned normative documents only emphasize the regulation and risk prevention of Bitcoin transactions. This regulation prohibits specific business behaviors of specific business entities and has nothing to do with Bitcoin transactions legally held by ordinary citizens. If the conclusion that crypto-asset transactions are illegal is inferred from the above-mentioned normative documents, especially the denial of the property attributes of crypto-assets themselves, it actually confuses the illegality of transaction behavior with the illegality of transaction objects. From the perspective of macro-policy objectives, the purpose of the aforementioned regulatory documents prohibiting token issuance and financing and prohibiting banks from providing Bitcoin trading services to customers is to prevent and resolve financial risks and prevent illegal activities such as illegal fundraising, rather than characterizing crypto asset transactions themselves as "illegal". The 2021 Notice follows the basic principles of maintaining the stability of the domestic financial market and preventing systemic risks, and imposes strict restrictions on domestic crypto asset-related business activities and crypto asset-related services provided by foreign countries to domestic residents. However, it excludes "providing crypto asset-related services from domestic countries to foreign countries" from the scope of restrictions, reflecting the country's implicit openness to crypto asset trading activities that do not affect economic stability and do not pose financial risks at the macro-policy level.

From the perspective of the legality of regulatory documents, the current "ban-type" regulatory content actually violates the provisions of Article 80 of the Legislative Law - without the provisions of laws or administrative regulations, regulations shall not empower themselves, shall not reduce citizens' rights and freedoms, and shall not increase their obligations. As a regulatory document with the lowest legal effect, it has no authority to directly create provisions that reduce citizens' rights and increase their obligations. The definition of "illegal and irregular behavior" in the aforementioned "Notices" and "Announcements" has essentially broken through the scope of effectiveness of normative documents and has formal legal defects.

The aforementioned denial of the "illegality" of crypto asset transactions actually recognizes that under the current legal system framework, although there is no positive law provision, it does not exclude the legal space for crypto asset transactions. This is in line with the trend of taxation gradually shifting from "policy rule" to "law rule" in the era of implementing tax legality. The new problem is that although it can be concluded that the taxation of crypto assets is "not illegal", this also means that crypto assets and the behavior of taxing them are indeed in a gray area in the existing law. Similar to the "gray income" or "gray industry" in the field of tax law research, it is difficult to independently prove the legality of crypto asset taxation based on "transaction legality". For this, it is necessary to return to the basic principles of tax law to explore the basis.

The most basic requirement for the "legal" taxation of crypto assets is not to violate the principle of "tax legality", because the rule of law principle has been established in the country's political life, and the government should tax according to the law, which is a self-evident requirement of modern tax law. The traditional principle of "taxation by law" requires that the substantive taxable elements be clearly stipulated by law. On the surface, crypto assets do not seem to comply with the principle of "taxation by law", and therefore do not have "legitimacy". However, with the development of the times, the legal connotation of the principle of "taxation by law" has been continuously expanded, and its requirements have gradually changed from strict statutory to the theory of taxation by law. At present, the principle of "taxation by law" is not a strictly unified "rule", but a flexible spectrum that distinguishes the statutory degree of various taxes. In short, "no clear legal provisions" cannot directly indicate that taxing crypto assets violates the principle of "taxation by law", but can it be used to indicate that crypto assets "should" be taxed? In this regard, we need to respond to the legacy issues at the level of "transaction legitimacy": Do crypto assets belong to "gray industries" and should "gray industries" be taxed?

There is no clear definition of "gray industries". In the past academic discussions on "gray income", it can be understood as "income (industry) that is not protected by law in civil legal acts and does not trigger the sanctions of other departments' laws". As for crypto assets, the current civil law does not have any provisions on crypto assets being "unprotected", but there are cases where judicial practice cites the aforementioned normative documents to determine that crypto assets are "not protected by law". For example, a court in Shandong Province ruled that the parties' trading of crypto assets "is a personal freedom, but cannot be protected by law" based on the 2017 "Notice" that crypto assets "do not have the same legal status as currency". At the same time, the holding, trading or investment of crypto assets by natural persons does not constitute "criminal violation" or "administrative violation". China's criminal law does not set up special crimes for holding or trading crypto assets. If crypto asset trading and other related behaviors follow the principle of good faith and are not suspected of fraud, theft, bribery, money laundering or illegal issuance of securities, the relevant behaviors are not criminal violations. As mentioned above, the content of administrative normative documents does not involve the effect of "administrative sanctions". Therefore, crypto assets are partially classified as "gray industry" at the level of normative documents and judicial practice. There is currently a conflict of views between the practical and theoretical circles on whether it is legal to tax "gray industry". There are two objections: First, the continuation of the basic civil legal relationship is the premise and basis for the establishment of tax claims. If "gray assets" are not protected by law, their legal effect is usually manifested as "invalid civil legal acts", which means that there is no basic civil legal fact for taxing them. Even if they have been taxed, they should be refunded. Its legal logic is similar to the effect of restoring the status quo caused by the invalidity of the contract. Some practical experts have further distinguished "invalid civil legal acts that can be restored to the status quo/cannot be restored to the status quo" to explore it. Second, if the tax authorities make a tax decision, as long as any party claims that the contract is invalid and is ordered by the court to restore the status quo, the tax authorities must refund the tax, resulting in a waste of administrative resources, which is neither reasonable nor necessary.

The above viewpoints are reasonable to a certain extent, but whether they can refute the legitimacy of taxing crypto assets remains to be discussed. First of all, the view that "gray assets" lack basic legal facts and should not be taxed is a one-sided understanding of the principle of substantive taxation. The original meaning of the principle of substantive taxation is "when interpreting tax laws, it is necessary to consider their legislative purpose, economic significance and the development of the situation." It can be seen that taxation should focus on the "economic purpose and essence of economic life" of the taxable object rather than the judicial judgment result. With the deepening of research in the field of tax law, the principle of substantive taxation has developed two interpretation paths: legal substantive taxation and economic substantive taxation. In the practice of tax collection and management, the tax department can independently determine the civil legal relationship involved in the case based on the principle of substantive taxation. If the tax department is forced to judge the tax-related facts from the perspective of judicial trial, it will unreasonably increase the cost of tax collection and management, and it will not meet the requirements of tax efficiency. In theory, any "income" that exists should be included in the scope of taxation. This is a reasonable response to the "causelessness of the source or basis of income" or even the "causelessness of taxation as modern law." In addition, the view of "wasting administrative resources" actually confuses the boundaries between different links of tax collection and management. In the identification of tax sources and the implementation of taxation, the principles of substantive taxation and tax fairness should be strictly adhered to, and taxation should be strictly levied according to economic substance. Even if a tax refund decision is made in the tax refund link, it should not affect the rationality of the taxation link, not to mention that the tax refund issue in the revocation of civil legal relations is still controversial. There is a lack of clear legal provisions for linking the revocation of civil legal acts with tax refunds, and there are clear legal provisions in practice. The judgment clearly stated that the "legality" of taxation is not affected by the revocation of the underlying legal act. Therefore, the above-mentioned opposing views are difficult to stand on their own.

In summary, there is room for "legality" in crypto asset transactions themselves. Even if crypto assets currently belong to the category of "gray industry", there is still sufficient legal basis for taxing them.

(II) Reasonableness of taxation of crypto assets

Reasonableness is a higher-level test of the taxability of crypto assets on the basis of legality, requiring it to comply not only with external legal forms, but also with the internal spirit of the rule of law such as fairness and justice. Comprehensive response to legality After the problem, crypto asset taxation faces another obstacle, that is, whether it is necessary to "make a big move" against crypto assets. In other words, whether the rational basis for crypto asset taxation can reach the level of "legitimate" and "necessary". Therefore, the rationality of crypto asset taxation should be more carefully analyzed in terms of rationality standards and structures, and whether crypto asset taxation meets the rationality standards.

Whether the system is reasonable or not depends to a large extent on whether the system needs are sufficient, but the system needs themselves vary with the different stages of the system. Considering that the function of the tax system is closely related to the theory of the enterprise life cycle, referring to the general rules of this theory, it can be The stages of tax collection and management systems are divided into the embryonic stage, growth stage, mature stage and decline stage. Usually, the stability and standardization of the regulatory system correspond to the institutional characteristics of the mature stage and the decline stage, but this is not the case. China's crypto asset market is still in the middle stage of the transition from the growth stage to the mature stage. The reasons are as follows: First, although China has issued a number of documents on crypto asset transactions, it lacks market management mechanisms such as active reporting and passive supervision, and there are problems with imperfect mechanisms, which do not meet the institutional characteristics of the mature stage and subsequent stages; second, there is a huge hidden market under the appearance of China's "ban on crypto asset transactions" policy. In addition, Bitcoin EFT (Exchange Traded Funds) was approved for listing and trading by the U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) in January 2024, showing great market vitality. As of early August 2024, the global scale of Bitcoin EFT has stabilized at around US$48 billion. With the approval of the Securities and Futures Commission (SFC) of Hong Kong, China, Bitcoin EFT will enter the trading scope of Hong Kong licensed exchanges in 2024. The current market size is around US$250 million, which is potentially attractive to future mainland investors.

After clarifying the current stage of tax collection and management of crypto assets in China, the rationality standard of taxation on crypto assets can also be further clarified. The main function of the tax collection and management system in the growth stage is to scientifically macro-control and ensure the stable and orderly development of the market, while the fiscal fundraising function is inferior. The tax collection and management system in the mature stage focuses on the fiscal fundraising function, thereby indirectly guiding market behavior. Therefore, the rationality of China's crypto asset taxation at this stage should be judged from the perspective of "macro-control law".

First, in the context of tax modernization and service-oriented national governance transformation, making full use of the national governance efficiency of the tax system to guide the development of the crypto asset market is an important means to adhere to the market economy system. Taxation of crypto assets is conducive to implementing the principle of taxation based on ability and ensuring equal tax burden in the market.

Secondly, more and more countries and regions are aware of the "decentralized" and "self-regulatory" characteristics of crypto assets, which are "attractive to those who want to engage in illegal activities or support dissident organizations", so countries are actively carrying out anti-tax avoidance and anti-tax evasion system practices. Taxation plays a fundamental, pillar and guarantee role in the national governance system. The role of taxation cannot be absent, and China's tax law should do more. At a time when the digital economy is booming, excluding crypto assets from China's tax law framework is not conducive to preventing and controlling illegal financial activities such as money laundering, and creates greater loopholes in the tax law framework.

Finally, vigorously developing new productivity and pursuing high-quality economic development have become new trends in economic development, which puts higher requirements on the allocation of economic resources. The allocation of resources mainly depends on the perfection of the system, otherwise "structural compensation" will occur, resulting in the support and stimulation of new productivity being difficult to be fully digested by the existing system, which will lead to waste and escape of resources. At present, the field of metaverse and crypto assets, as the frontier of scientific and technological development, is the key area of new productivity development and economic resource investment. Therefore, there is sufficient reason to believe that there are potential tax resources that are "abandoned but a pity", so it is necessary to improve the relevant tax collection and management system.

From the perspective of overseas practices, the United States continues to improve the tax collection and management system of crypto assets and strengthen its tax supervision policies. Under the premise of emphasizing the disclosure of transaction information and preventing false or concealed declarations, the UK is actively exploring ways to improve the competitiveness of its tax system, with the ultimate goal of making the UK a global crypto asset technology and innovation center. The rest of the EU countries are also actively establishing a coordinated and unified crypto asset tax policy, such as imposing a 30% unified tax on the sales proceeds of assets including cryptocurrencies and NFTs. Germany and Japan maintain a highly open taxation attitude towards crypto assets, recognize the legitimacy of their means of payment, and directly incorporate them into the existing tax law framework. Therefore, the rationality of crypto asset taxation has a broad overseas practice basis as a reference.

It must be emphasized that a country's taxation policy is closely related to its tax system, and a country's tax system should truly reflect a country's economic situation and actual needs. Overseas crypto asset practices may not have direct reference value for China. However, the national tax system is an important support for the opening up of international economic exchanges. Whether China's tax collection and management framework can effectively connect with the tax framework of the world's major economies is an important component of promoting the establishment of a win-win international tax system and promoting international tax exchanges and cooperation during the "14th Five-Year Plan" period. The crypto asset market naturally has the characteristics of cross-border flow and global commonality, which determines that it is necessary for China to take crypto assets into consideration when establishing an open tax framework. Economic globalization enables economic elements to flow more freely across borders, and the mobility of tax bases has also greatly increased. Combined with the differences in tax systems of various countries and the profit-seeking mentality of taxpayers, a "tax competition market" has emerged. Therefore, the issue of taxation of crypto assets should not be simply limited to the region, but should use multilateral governance thinking, actively participate in global tax governance, and seize the initiative of the tax system in interdependence.

In summary, the taxation of crypto assets is consistent with the background, goals, and requirements of China's future tax collection and management system reform, and its rationality has sufficient theoretical and practical support.

(III) Feasibility of taxation of crypto assets

The general view is that taxation has compulsory characteristics, including the compulsory establishment of tax distribution relations, the compulsory taxation procedures, and the ultimate realization of taxation through the state's political power. However, the compulsory nature of taxation cannot directly constitute the basis for the feasibility of taxation. Some scholars have proposed the "feasibility of taxation", which is an indicator that measures whether relevant factors can be correctly and conveniently collected into the national treasury from a technical perspective for tax collection and management. It can be divided into two levels: tax feasibility and collection and management feasibility.

From the perspective of tax feasibility, "feasibility of taxation" depends on the tax basis and element characteristics of the taxable object. The issue of tax feasibility is essentially the "tax base" issue of crypto assets. The tax base is different from the taxable object itself. There may be multiple tax bases for the same taxable object. If there is a reasonable and appropriate tax base calculation plan for a taxable object, it should be considered feasible to tax the object. For this, it is necessary to comprehensively examine the calculation plan of the tax base of crypto assets. It can refer to the existing theoretical results of the data tax base and divide it into three different types: tax base calculation based on quantity, tax base calculation based on value, and tax base calculation based on income.

First, the tax base calculation plan based on quantity. This plan was born in the digital economy era with the improvement of the economic status of intangible assets and non-physical services. The Bit Tax in practice is a typical example. However, the Bit Tax uses the "number of network data transmissions" as the tax base, which no longer has a realistic environment. The smallest unit of measurement for crypto assets is not "each" piece of data, but a collection of data, and the value attribute of crypto assets determines that "data content" is more important than "data quantity", and the tax base calculated by quantity cannot be applied to the taxation of crypto assets.

Second, the taxation scheme that calculates the tax base by value. This scheme is essentially a traditional "value-added" tax base scheme, strictly adhering to the principle of "volume-based taxation". The higher the value of the taxable object, the stronger its tax-bearing capacity is presumed to be. This approach is conducive to the fairness of tax collection and management, but there are two shortcomings: First, the taxation scheme is inconsistent with "profitability" while demonstrating "taxability". Taxes are only levied when there is income on the taxable object. If the income directly related to the tax-bearing capacity is not considered and the tax-bearing capacity is measured by value, it is inconsistent with the general principle of taxation. Second, the judgment of the fair value of crypto assets is greatly affected by factors such as scenarios, uses, and time. It is difficult for its value to exist in a relatively fixed static state, and the measurement lacks operability.

Third, the taxation scheme based on income. This scheme pays more attention to the "increase in benefits" of the taxable object in the acquisition, holding and circulation links, as well as the interactive feedback between the taxable object and the external environment. Whether to calculate the tax depends on whether the value of the taxable object can be confirmed, that is, whether there is income. Therefore, it can overcome the shortcomings of the above two taxation schemes when facing crypto assets. However, the scheme based on income to calculate the tax base also has limitations. Although income measurement can overcome the technical problems encountered in the value measurement process to a certain extent and is more operational, in the context of crypto asset taxation, it is not possible to reliably measure the "full life cycle" income from birth to circulation, because the generation of crypto asset income depends on its interaction with the external environment. In the simple holding link, crypto assets do not show income to the outside world, or it is difficult to observe the income of the holding link with the current regulatory measurement technology, so the scheme based on income to calculate the tax base is difficult to cover all economic links of crypto assets. But on the whole, considering the urgency of taxation needs and the current status of tax collection and management technology, the scheme based on income to calculate the tax base can better meet the feasibility of taxation.

From the perspective of the feasibility of taxation, the "feasibility of taxation" depends on whether the aforementioned tax base scheme can be actually implemented, that is, whether the tax base itself can be conveniently and reasonably priced. In this regard, it can be further divided into two aspects: legal standards and technical solutions: in terms of legal standards, such as the aforementioned refutation of the misuse of normative documents in the Supreme Court's Guiding Case No. 199, if the use of legal currency to price crypto assets and its property attributes are denied, it will not only hinder the realization of damages in civil cases, but also cause huge obstacles to the conviction and sentencing of criminal cases involving currency. Even as judicial professionals have said, the conclusion that stealing other people's Bitcoin private keys and transferring a large number of Bitcoins cannot be determined to constitute a crime will seriously damage the unity of the legal order. Measuring the price of crypto assets with legal currency in crypto asset transactions is also an important link in improving the quality and effectiveness of judicial relief. Under the premise that there is no clear denial in the current laws and administrative regulations of the State Council, the use of legal currency as the tax base of crypto assets should be determined to be legal, reasonable and feasible, thereby providing legal standards for the feasibility of taxation. In terms of technical solutions, the anonymity, cross-border liquidity, irreversibility and decentralization of crypto assets as potential tax sources determine that there are technical difficulties in imposing tax supervision on them, which is mainly reflected in the information asymmetry between tax authorities and taxpayers caused by insufficient capacity of tax authorities. In response to this, the tax collection and management system can be improved by using blockchain technology. The logical starting point of the dilemma of crypto asset supervision lies in decentralized blockchain technology. Based on the irreversibility and non-tamperability of blockchain technology, it can be reversely applied to the field of tax collection and management, and digital assets can be implemented for information collection and management. The blockchain application of electronic invoices can be strengthened to provide sufficient and accurate evidence for events that generate tax disputes, ensure the integrity of the transaction process, improve the efficiency of tax collection and management, and promote the transformation from "tax control by invoice" to "tax control by numbers". For taxpayers' malicious tax evasion and tax fraud, the recognition algorithm of blockchain technology can effectively detect taxpayers' illegal behaviors and help tax authorities verify illegal and irregular behaviors using blockchain databases. At the same time, it cooperates with the construction of a tax declaration system that adapts to the characteristics and transaction patterns of digital assets to provide convenience for taxpayers, thereby reducing the tax costs of both tax authorities and taxpayers and improving the efficiency of tax governance.

In summary, after clarifying the feasibility of crypto-asset taxation, we can focus on the practical exploration of the path of crypto-asset tax law governance.

On the premise that the taxability of crypto-assets is recognized by tax laws, another major challenge it faces is how to arrange the specific tax system for crypto-assets, that is, how to use the existing tax system framework to properly place crypto-assets in it, so that different types of crypto-assets can "get what they deserve" and coexist in harmony with the current tax system. In recent years, many countries have started to practice taxation of crypto-assets, especially the United States, which has rich experience in crypto-asset tax practices and systems. The Internal Revenue Service (IRS) of the United States has issued IRS2014-21 guidance, which clearly stipulates that crypto assets represented by Bitcoin should be taxed according to the tax law requirements of general property. After that, the IRS further clarified that the relevant income of cryptocurrencies in the initial acquisition stage should also be included in the taxable income and tax should be paid. At the same time, it is stipulated that the gift of cryptocurrencies and the transfer of cryptocurrencies between different digital wallets of the same owner are not taxable behaviors. The United States clearly stipulates in the resident tax return (Form 1040) that individuals need to fill in "whether there is any economic benefit from receiving, selling, sending, exchanging or otherwise obtaining any virtual assets in the previous year" when reporting. This tax reporting method is very feasible. Looking back at past tax law research, it can be found that most of the research on tax governance of a single taxable object or a certain type of taxable object is on tax governance, and the overall tax governance framework for crypto assets has not yet been established. Taking the product growth link of "acquisition-circulation" of crypto assets as a clue, specifically analyzing the tax issues in each link, and building a tax governance framework for the entire process of crypto assets can provide an institutional basis for subsequent practice.

(I) Taxation path in the acquisition stage

The first controversy about taxation issues in the acquisition stage of crypto assets is the question of what kind of tax obligations arise. Some scholars regard the production process of crypto assets as a kind of resource mining behavior and believe that digital resource taxes should be levied on them. The production method of crypto assets under the proof-of-work mechanism (POW) is called "mining". Its scarcity has something in common with non-renewable natural resources in nature. This feature provides strong support for the construction of a "digital resource tax". However, in terms of current tax practices and the development stage of crypto assets, the time is not yet ripe for the construction of a "digital resource tax" for the following reasons.

The legal logic behind the "resource-based" tax item is "beneficiary pays". Taking the natural resource tax as an example, its legitimacy lies in the fact that as natural resources owned by a sovereign state, state ownership means ownership by the public. The improvement of public welfare has public economic benefits for society. Natural resources are developed, collected, and processed by a few individuals, which can be regarded as concentrating public economic benefits on individuals, so it is necessary to "compensate" the public group. In addition, the non-renewable and ecological protection characteristics of natural resources require developers to pay a corresponding price for the reduced public ecological interests. Crypto assets are significantly different from this. Crypto assets are less public welfare. Although blockchain technology represented by public chains can bear some public information recording functions, its value is still "personal interests". "Mining" behavior is difficult to say that it divides and reduces public interests, and there is insufficient basis for requiring developers to directly bear the price for "mining" behavior. The scarcity of crypto assets is not as absolute as natural resources. In particular, the emergence of crypto asset circulation platforms that "embed" smart contracts into blockchain technology, represented by Ethereum, has widened the gap between crypto assets and general natural resources. Therefore, it is not appropriate to classify existing crypto assets into the field of "digital resource tax" to discuss tax treatment, but to seek ways to regulate crypto assets within the current legal framework, that is, to conduct typological analysis based on different crypto asset acquisition modes. This can not only meet the different tax characteristics of different types of crypto assets, but also avoid setting up new tax types outside the current tax system, thereby causing administrative inefficiency and additional legislative burdens. Specifically, there are three typical ways to acquire crypto assets, namely mining, forging and airdrops, and there are fundamental differences in the economic connotations of different acquisition methods.

As far as "mining" is concerned, the basic logic of acquiring crypto assets is the "proof of work" consensus mechanism. The "mining" behavior can be divided into the basic data recording behavior and the incidental bookkeeping right reward acquisition behavior. Regardless of the subjective purpose of the "mining" behavior, it objectively constitutes a component of the "consensus mechanism" of crypto assets, which is equivalent to providing network security and bookkeeping services for the blockchain decentralized ledger system as an individual "miner". The essence of "mining" is that the "miner" provides "services". According to the current tax law system, this behavior simultaneously triggers the occurrence of value-added tax and income tax obligations. Although the crypto assets themselves have not yet been acquired for the value-added tax part, the taxable behavior of the "miner" has gained value in the circulation link of the decentralized ledger system. Even if the crypto assets obtained by "mining" have not entered the circulation link, the taxable behavior of the "miners" behind it has been separated from the individual external circulation and has increased in value, so value-added tax should be paid. Considering that its economic essence is equivalent to providing network technology information services, it should be subject to a low tax rate of 6% in accordance with the "modern services-information technology services" in the general tax scope of value-added tax. As far as income tax is concerned, the income obtained by "miners" from "mining" behavior includes newly issued crypto assets and handling fee income, which can be regarded as the actual compensation for their service provision. According to the logic of the proof-of-work consensus mechanism, this belongs to the "labor remuneration income" obtained by "miners" for providing labor services for decentralized ledgers. At the same time, considering that there is no employment relationship between the decentralized ledger system and the "miners", the income does not belong to "wage and salary income". Individuals can be included in the personal comprehensive income after deducting 20% of the expenses and apply the seven-level excess progressive tax rate. Enterprises can calculate and pay corporate income tax after deducting relevant costs.

As for "forging", the basic logic of crypto asset acquisition is the "proof of equity" (POS) consensus mechanism. The probability of a user obtaining a crypto asset (represented by Ethereum) depends on the size or amount of its coin age, which is similar to the number of shares a company shareholder has. In the proof-of-stake mechanism, newly issued or forged crypto assets are distributed according to the size of the coin age owned by the user, and are exclusively granted to one of the users. The coin age affects the probability of being granted. This probability-based design encourages users to actively circulate and use the crypto assets they hold, which can enhance the liquidity of crypto assets. Although the process of forging crypto assets is similar to the company's distribution of dividends according to shareholder equity, considering that the essence of the proof-of-stake mechanism is still a probabilistic design, unlike the "equal distribution" of equity investments such as dividends and bonuses, the acquisition of crypto assets through forging is essentially accidental income such as winning a prize or lottery, and personal or corporate income tax should be paid at a 20% tax rate in accordance with accidental income.

As for "airdrops", their essence is that the issuer gives crypto assets to users for free for the purpose of corporate publicity and attracting users. For the recipients, it should be considered accidental income as obtained through "forging", and income tax should also be paid at a 20% tax rate.

(II) Taxation path in the circulation link

In terms of income tax in the circulation link, the above has clearly proved that crypto assets have property attributes recognized by tax laws, and income tax can be levied uniformly according to the tax item of "property transfer income". The tax disputes in its circulation link focus on the "value-added generated by circulation", which is mainly manifested in three situations: first, the use of crypto assets to exchange for other crypto assets; second, the transaction between crypto assets and legal currency; third, the use of crypto assets in exchange for physical goods and services. Considering that the current attitude of China's financial regulatory policy towards the circulation of crypto assets is to completely deny its "payment function", not recognize its exchange with legal currency, and not recognize it as a legal trading medium, the "repayment agreement" in practice should be understood as "barter". Under this premise, crypto assets should be divided into homogeneous and non-homogeneous methods, and the specific tax treatment under different circulation scenarios should be discussed separately.

1. Taxation path for homogeneous crypto assets

Homogeneous crypto assets can be specifically divided into cryptocurrencies and crypto-tokens according to whether they have the function of being exchanged for legal tender.

(1) Cryptocurrencies

As far as cryptocurrencies are concerned, some of them are directly classified as legal tender by some countries. For example, Venezuela classifies the Petro as legal tender, and the Marshall Islands classifies the Monarch as legal tender. In addition, some countries include them in the tax system as foreign exchange. China currently has a negative attitude towards "payment-type cryptocurrencies" and it is not appropriate to classify these "legal tender" cryptocurrencies recognized outside the region as foreign exchange. Considering the need for international tax coordination and coordination between foreign exchange management and financial supervision, "legal tender" cryptocurrencies can be temporarily classified as financial products, which is consistent with the tax practices in some parts of China.

Similarly, stablecoins anchored to legal tender have the characteristics of financial products. For example, Tether (USDT) maintains a 1:1 exchange ratio with the US dollar, and the issuer claims that its collateral account always maintains an equivalent amount of US dollars or corresponding assets as reserves. Although this stablecoin has not been recognized as legal tender in overseas practices, considering the close correlation between its price and the legal tender it is anchored to, the U.S. Commodity Futures Trading Commission (CFTC) regards it as a "retail foreign currency option", so this stablecoin is essentially similar to a financial derivative of the foreign exchange index.

In addition, the most mainstream cryptocurrencies such as Bitcoin are neither characterized as legal tender by most countries nor anchored to a certain legal tender. Its main function is to serve as an investment tool and a carrier of value storage. Such cryptocurrencies are suitable for characterization as ordinary goods, which is consistent with the Chinese normative documents that characterize them as specific virtual goods. It can be seen from this that the first two cryptocurrencies, because they have the attributes of financial commodities, should be classified as "transfer of financial commodities" tax items and the value-added tax should be calculated at 6% using the difference tax method. General cryptocurrencies that are not legal tender and not anchored to legal tender are classified as "sales of ordinary goods" and the value-added tax is calculated at a general tax rate of 13%.

(2) Crypto tokens

There is some practical experience in the tax treatment of crypto tokens. For example, the European Commission once stated in an official letter: "For the purpose of EU VAT, all types of electronic transactions and all intangible products delivered in this way are considered services." The above conclusion is only for reference, and qualitative conclusions that are in line with local reality should still be explored based on China's current laws.

In the issuance of crypto tokens, some of them are issued for the purpose of exchanging for goods or services provided by the issuer in the future, such as Ethereum. Although these crypto tokens are often used as transaction media or investment tools in actual transactions, considering that general debts may also play a role as media and investment in real economic activities, it should be considered that their nature is still similar to traditional debt certificates. In contrast, some crypto tokens represent the issuer's residual value claim or membership rights at the beginning of issuance, such as DAO equity tokens. Their nature is similar to traditional equity certificates, which should be discussed separately. First, the cryptographic tokens that constitute debt certificates can be regarded as the issuer's financing by issuing cryptographic tokens. In terms of function, they are similar to single/multi-purpose prepaid cards in electronic form, or recharged savings cards issued by physical merchants. The VAT taxable behavior should occur when the goods or services are actually exchanged, and the VAT rate should also be determined according to the actual exchange object. A uniform tax rate standard should not be set; second, the cryptographic tokens that constitute equity certificates should be characterized as equity intangible assets. Some scholars believe that equity cryptographic tokens belong to the category of "securities", but the definition of securities in the Securities Law of the People's Republic of China adopts an enumerated definition, and equity cryptographic tokens do not meet the legal definition of typical securities. In addition, most equity tokens represent decentralized governance rights, which are different from centralized corporate governance rights. Equity tokens essentially represent membership rights and residual value claims, which can be classified as equity intangible assets stipulated by tax laws, and are managed in accordance with "membership rights" and "seat rights", which is consistent with the practice of some tax authorities to classify crypto assets as intangible assets.

Some crypto assets with creditor's rights characteristics, such as Ethereum, which adopts the proof-of-stake consensus mechanism in the Ethereum 2.0 iteration, have the characteristics of equity certificates and blur the aforementioned classification boundaries. Classifying them one by one is conducive to clarifying the tax collection and management path, but it may cause problems such as the difficulty of tax authorities in identifying different types of crypto assets, resulting in unreasonable increase in tax collection costs. Considering that the iteration of crypto assets is still in a rapid development stage, it is advisable to use the acquisition link mechanism as the standard at this stage to simplify the identification method so as not to fall into the trap of unlimited classification. According to this, the Ethereum generated by the proof-of-stake mechanism mentioned above should be classified as an equity token and taxed at the 6% tax rate of the aforementioned equity intangible assets.

2. Taxation path for non-homogeneous crypto assets

As the mainstream representative of non-homogeneous crypto assets, NFT has a relatively short development time. It is commonly known as "digital collectibles" in China. In practice, it includes at least on-chain tokens (carrier layer) and their mapped digital works (mapping layer). There are many disputes about its legal status. In terms of judicial practice, in the first NFT transaction case in China, the court defined NFT as blockchain metadata that marks specific digital content, which is itself an abstract information record. In other words, NFT is recognized as "data" in practice, that is, digital voucher. At present, China's value-added tax system has not yet clarified the tax law positioning of "data". An examination of the value-added tax system shows that there are many elements related to "data", including "intangible assets", "audio-visual products", "electronic publications", etc., so the tax law nature of NFT needs to be further clarified.

Considering the technical structure of NFT, it can be seen that it conforms to the hierarchical structure of "physical layer-symbol layer-content layer". The NFT metadata of the "symbol layer" links the information recorded in the NFT of the "content layer" through the URI part inside the metadata. URI saves information about how to read data, plays the role of "locating" data resources, and realizes the mapping function of NFT to off-chain property. NFT usually only contains its storage address, which can be regarded as the "player" and "display screen" of digital works. In the public chain technology environment, when NFT is traded, not only its content and rights are transferred to the transferee, but the metadata of the data file also needs to add the transaction record and transaction information, that is, the "symbol layer" and "content layer" are transferred simultaneously in one transaction. The essence of NFT is refined from the broad "data" to "a unique digital certificate stored on the blockchain, which is used to verify the existence and ownership of assets, but is different from the assets themselves". Although its accompanying rights (i.e., the "content layer") are transferred simultaneously with the NFT data file, they are relatively independent of the NFT metadata file, that is, the existence or extinction of the NFT itself does not affect the existence or extinction of the property (digital work) it maps. This situation is similar to the destruction of the real estate itself, the ownership basis is directly eliminated, but the real estate certificate still exists. Conversely, the elimination or not of the real estate certificate does not affect the existence of the real estate. There are even cases where the NFT minter immediately destroys the physical rights and interests object mapped by the NFT (such as a painting on a paper carrier) after the NFT is produced. This behavior will not destroy the value of the NFT itself, but will make the NFT a "lonely piece" and thus increase its price, which can further prove the binary separation between the NFT data file and the data content.

In view of this, the VAT taxation arrangement for NFTs should conform to the binary separation characteristics and tax data files and data content separately. NFT data files meet the definition of "electronic publications" and have physical storage and interactive functions, and should be subject to a lower VAT rate of 9%. At present, when the tiered taxation system for data elements is still under discussion, NFT data content should still be regarded as a kind of "equity intangible asset" and the 6% VAT rate should be applied according to the sales of intangible assets.

Using the existing tax system to regulate crypto assets is conducive to reducing legislative costs, following the tax practice orientation, taking into account the efficiency and feasibility of establishing an independent system, and making crypto assets, a long-term "avoided tax source", receive attention from tax laws. By reconstructing the taxability theory, we can provide ideas for breaking the barriers to taxation of crypto assets. On this basis, we can divide the acquisition link and the circulation link, and construct the taxation path of crypto assets respectively. In the acquisition stage, the economic nature of different acquisition methods should be distinguished from "mining", "forging" and "airdrop" for analysis. In the circulation stage, the content and mode of crypto asset transactions directly affect the basis for the establishment of the tax system. It is necessary to distinguish the different transaction scenarios of homogeneous and non-homogeneous crypto assets, treat them differently, and use the existing tax elements to return crypto assets to the vision of tax laws.

This article does not intend to deny the legitimacy and rationality of trying to build an independent "digital tax system", nor does it believe that the existing tax system can "eternally" cope with the future development trend of the digital economy. On the contrary, in the face of the trend of the digital economy 1.0 era dominated by platform economy to the digital economy 2.0 era with decentralized organizations and blockchain technology as the core, how tax laws can respond to the challenges of the times, whether the tax source governance and tax supervision of economic elements in the new era need new changes, and how to choose the tax dispute resolution mechanism, etc., all need to be further explored. Looking at the current situation of global crypto asset tax practices, although limited by the economic development status and tax system differences, there are large differences in the tax policies implemented by various countries for crypto assets, but in general, developed countries mostly identify the tax attributes of crypto assets as a financial asset or property, and improve the corresponding tax collection and supervision policies to cope with the rapid development of the crypto asset industry.