Source: Culture Horizon

Introduction

On May 10, 2025, the China-US high-level economic and trade talks were officially launched in Geneva, Switzerland. US Treasury Secretary Bensont, as the US leader, held a dialogue with China. The China-US talks have attracted global attention, especially the attention of Southeast Asia. Against the backdrop of intensified Sino-US competition, Southeast Asia, as a key region for industrial transfer and economic and trade cooperation, has become more uncertain. Vietnam has actively participated in the tariff negotiations with the United States. Three days ago (May 7), as one of the first negotiating countries, it announced that it had a "good start" and achieved "positive initial results". The recent India-Pakistan conflict may further promote Southeast Asia's "risk-avoidance" role in the industrial chain and further divide regional economic integration.

This article reviews the development path of Southeast Asia after the war. Under different international political structures, Southeast Asia has participated in the international economic and trade cycle through the flying geese model and value-added trade. With the return of geopolitics, Southeast Asia's trade model is entering the third trade form. Vietnam and Malaysia are simultaneously taking over the industrial transfer from China and the United States, but they face the risk of strategic alignment. The key to the upgrade of US-Vietnam relations lies in the US's commitment to help Vietnam develop the semiconductor industry and rare earth industry, which is related to the core areas of competition between China and the United States. In addition, Malaysia, with its mature electronic manufacturing industry and logistics advantages, is becoming one of the biggest beneficiaries of the Sino-US semiconductor competition.

The author points out that in the face of changes in Southeast Asian trade patterns and structures, China, with its super-large market, has a lot of room for adjustment. As long as it adheres to an open and inclusive free trade policy, it can still greatly delay or even avoid the separation and "decoupling" of economic and trade relations in East Asia. But what cannot be ignored is thatthe United States is vigorously supporting countries with better conditions among Southeast Asian economies, trying to replace China's position in the East Asian production chain from both high and low directions.

This article was originally published in "Cultural Horizons" Issue 4, 2024, with the original title "Southeast Asian Development Model in the Changing Game of Great Powers" and only represents the author's views for readers' reference.

Southeast Asia's development model in the changing game between great powers

Against the backdrop of the intensified game between China and the United States, the importance of Southeast Asia has become more prominent. Compared with the beginning of the 21st century, Southeast Asia (ASEAN) today has become a dazzling presence on the world stage. According to purchasing power parity(PPP), ASEAN as a whole is the world's fifth largest economy, second only to China, the United States, the European Union, and India, and its share of the world economy has increased from 5.0% in 2001 to 6.4% in 2023.Since the 21st century, Southeast Asia's economic growth has also been eye-catching, with the world economy growing at an average annual rate of about 3.0%, Southeast Asian countries at an average annual rate of 5.0%, and Indochina countries at nearly 7.0%. In the field of trade, ASEAN countries are also an important force, with their share of world merchandise exports increasing from 6.2% in 2001 to 7.6% in 2023, almost equivalent to the exports of Africa and Latin America as a whole. In addition to the economy, all major powers are competing to befriend ASEAN. Not only do they all recognize ASEAN's "central position", but they also take into account the participation of Southeast Asian countries in many regional economic and trade agreements. What is particularly striking is that ASEAN countries have participated in the "Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership Agreement" (RCEP) promoted by China, and many member states have also participated in the exclusive "Indo-Pacific Economic Framework" (IPEF) led by the United States.

The geopolitical and geo-economic competition between China and the United States is intensifying, and the impact of major power competition on economic and trade issues is expanding. So is the development space of Southeast Asia, which is located between the major powers, shrinking or expanding? For China, in the face of US pressure and containment, how can it further consolidate China-Southeast Asia relations, and can Southeast Asia be used as a strategic focus? These questions are not only of practical significance, but also of strong theoretical significance. Understanding the development of Southeast Asia in the context of intensified geopolitical competition requires not only attention to prominent phenomena in the security field such as hedging and taking sides, but also the impact of changes in the order of economic division of labor on political relations.

Flying Geese Model and the Development of Southeast Asia

Measured by GDP per capita calculated by purchasing power parity, Asia's overall development level has been lower than that of Latin America and sub-Saharan Africa for a long time. In the 1950s, Argentina's per capita GDP was about 50% of that of the United States, while that of Southeast Europe and the Caribbean was close to 30% of that of the United States. In 1950, Asia's per capita GDP was less than 8% of that of the United States, and the per capita GDP of East Asian economies was about 7% of that of the United States, of which China, India, and Japan accounted for 4.7%, 6.5%, and 20.1% of that of the United States, respectively. The rise of East Asia has changed this situation. The countries that developed earlier and faster are Japan, the "Four Little Dragons" in Asia, and several countries in Southeast Asia. The development of East Asian countries has been sequential, but they are basically on the track of gradual development, which is a common feature of most countries in East Asia. By the early 1980s, the per capita GDP of Japan, South Korea, and Hong Kong, China reached 72.2%, 22.1%, and 56.5% of that of the United States, respectively, and the per capita GDP of Singapore, Malaysia, and Thailand reached 48.8%, 19.7%, and 13.7% of that of the United States, respectively. By the year when China joined the World Trade Organization (WTO), Singapore's development level reached 80% of that of the United States, South Korea's share rose to 52.6%, Thailand's share reached 22.8%, China's share also jumped to 13.2%, and India's share was still less than 7%. This gradual change process not only conforms to people's understanding of different regions, but also attracts the attention of the academic community. Among various early theories that study the driving force of East Asian development, the most influential is the flying geese model proposed by Japanese scholars. The main idea of the flying geese model theory was formed by Kojima Kiyoshi and his teacher Akamatsu Kaname in the 1940s. The area based on the Japanese colonial empire during World War II includes Taiwan, Northeast China, and the Korean Peninsula. During World War II, Japan attempted to establish the so-called "Greater East Asia Co-Prosperity Sphere" to promote the formation of a new regional order different from that of Britain and the United States, and Japanese economists also participated in it. After the end of World War II, such voices in the Japanese economics community disappeared for a time. After the progress of European integration, regional cooperation among Asian countries was put back on the agenda. These theoretical accumulations formed by Japanese scholars before the war became the theoretical basis for Japan to think about and deploy regional cooperation in Asia in the 1960s. The core of the flying geese model has three points. First, the development sequence from low to high between industries, from labor-intensive textile industry to capital-intensive and technology-intensive industries; second, countries with high levels of development transfer their outdated industries to countries with lower levels of development; third, development is gradual and step-by-step. After further development, countries at the second level of development will transfer the industries they have taken over from the first level countries to the third level countries. Therefore, the flying geese model has constructed a dynamic division of labor model of "industry × country" within a certain region. Correspondingly, the international trade pattern in East Asia during this period was dominated by a typical North-South trade pattern, with underdeveloped countries exporting natural resource products and labor-intensive manufacturing products, while Japan exported various capital-intensive and human capital-intensive manufacturing products.

By the mid-1990s, two prominent phenomena had caused people to question the effectiveness of the flying geese model. First, with the widespread development of the electronics industry in East Asian countries, the successive industrial replacement advocated by the flying geese model had become ineffective. Second, Japan lost in the trade competition with the United States and could no longer maintain a relatively closed regional production network. Like developed countries, East Asia also had extensive intra-industry trade, which was different from the flying geese model based on inter-industry trade.

After China joined the WTO, intra-industry trade in East Asia became more common and extensive, and Japanese scholars were still at the forefront of summarizing these phenomena. Kiyoshi Kojima continues to expand the flying geese model and emphasizes that the theory still has explanatory power in understanding industrial catch-up. In his book "The Rise of Asia", Terutomo Ozawa systematically discusses the phenomenon of group development of Asian countries and calls it "the growth cluster led by the United States". The basic unit of Ozawa's analysis and research is no longer the nation-state as in the past, but a region. This is a big change for economics; but for the discipline of international relations, the shift from country to region is not uncommon. His new contribution is mainly to thoroughly recognize the status of the United States (rather than Japan as believed by the flying geese model theory) as the leader, and to reintroduce the power factor into the study of industrial transfer in East Asia. In the late 20th century, with the rapid development of information technology, the division of labor within the industry has made rapid progress. Once the development of information technology is involved, the United States and the political and economic motivations behind its information technology cannot be bypassed.

Value-added trade and the development of Southeast Asia under the dominance of the United States

Under the United States' dominant position of power, research on intra-industry trade in the information age has led to new theoretical understandings. First, many countries embrace openness and join the international market through tax cuts, signing bilateral investment agreements and free trade agreements. Second, the United States has a prominent position of power. Although there are some voices against globalization in the United States, it still advocates globalization on the whole.

Under the influence of this trend of thought, the academic community has focused on studying the driving force and reasons for the rapid growth of international trade since the 1990s, and has described the progress of "vertical specialization trade". After entering the 21st century, scholars found through rigorous empirical analysis that 30% of the trade growth from the 1970s to the early 1990s was actually intra-industry trade, which means that more and more countries began to focus on a specific stage of commodity production rather than producing the entire commodity. Since the 1990s, intra-industry trade has further developed, and value-added trade with vertical specialization as its main feature has increased significantly, gradually forming a global value chain trade system. According to the authoritative statement of the World Bank, before the outbreak of the international financial crisis in 2008, global value chain trade accounted for more than 50% of global trade. Although it has stagnated since then, it has not declined.

This process has also greatly affected the development path and trade model of Southeast Asia. Since the early 1990s, East Asian developing countries that have joined the global value chain have also begun to export manufacturing products, especially mechanical products. The trade patterns of countries in the region are becoming more and more similar, and intra-industry trade(IIT)has become increasingly important. Since then, the international trade pattern in East Asia has rapidly shifted from inter-industry trade under the flying geese model to intra-industry trade.

The division of labor formed in international trade for a long time is that developed countries export finished products and developing countries export raw materials. When the poorer developing countries also begin to export finished products, new trade theories are needed to explain it. After the end of the Cold War, scholars in the United States, Europe, and Japan turned to the study of vertical specialization, which greatly enriched our understanding of the development of Southeast Asia. Thus, the second generation of development models based on intra-industry trade and added value trade were born. Why has East Asia established a stable international production/distribution network, while other developing regions, such as Latin America (except Mexico), have hardly succeeded? Why is East Asia's production/distribution network more complex than the US-Mexico relationship or the Western Europe-Central and Eastern Europe corridor? This actually reflects the major adjustments in the development strategies of East Asian countries.

The major event in the world economy in the 1980s was the US-Japan trade friction. When faced with competitive pressure from the United States, Japan has relied on Southeast Asia as one of its main sources of support. With the so-called "second unbundling", it outsourced labor-intensive production stages to neighboring low-wage Southeast Asian countries. This offshore outsourcing is also considered a source of Japan's comparative advantage in the European and American markets. Under the influence of Japanese multinational corporations, Southeast Asian countries have also developed rapidly. It is particularly noteworthy that Southeast Asia has also achieved success in exports in the fields of electrical and general machinery, just like Japan once did. Its share of the global economy exceeds the share of Southeast Asia's total economic output in the world. On the eve of the 2008 international financial crisis, global production had shifted significantly from mature industrial economies to developing countries, especially East Asia. Machinery and transport equipment, especially information and communication technology(ICT)products, electrical products have played a key role in the transformation of the export structure of East Asian countries, and China's rising position is becoming increasingly significant. Asia's share of world trade in machinery and transport equipment rose from 14.5% in 1995 to 42.4% in 2007, with exports accounting for more than four-fifths of the increase. By 2007, more than 58% of the total global exports of information and communication technology came from Asia, with China alone accounting for 23%. In terms of electronic products, China's world market share rose from 3.1% in the mid-1990s to 20.6%. In addition, with the exception of Singapore, the world market share of ASEAN countries has grown faster than the regional average.

China's rise and the third stage of Southeast Asia's development

After entering the new century, Southeast Asia's main form of participation in international trade is still value chain trade, which expands market share and expands the depth and breadth of participation in the global value chain by improving the level of specialization in a certain production link. However, China's economic rise has not only changed the trade network relations in Southeast Asia, but also significantly enhanced the impact of geopolitics on the evolution of value chains in the region. Early before its economic output surpassed Japan’s in 2010, China had already become the center of East Asia’s production network. This means that China and Southeast Asia have formed close economic and trade ties, and the development of Southeast Asia will inevitably be deeply affected by China’s foreign economic and trade relations, especially the impact of the Sino-US trade friction in 2018.

Today, the trade development of ASEAN countries can be briefly summarized into three different models. The first is the relatively developed Singapore, Malaysia and Thailand, where the proportion of exports to GDP is several times the world average, but all of them have passed the peak. Among them, Singapore’s peak exceeded 200%, which occurred during the 2008 financial crisis; Malaysia’s peak was 120%, which occurred during the 1997 East Asian financial crisis; Thailand’s peak was close to 70%, and it was a gentle peak that lasted for a long time, spanning the East Asian financial crisis and the international financial crisis. The second is the Indochina Peninsula countries, such as Cambodia, Laos and Vietnam, where the proportion of exports to GDP is still rising. Especially for Vietnam, the export share was temporarily lowered after the impact of the 2008 international financial crisis, but it exceeded the pre-crisis level in 2014 and rose to 90% in 2022. The third type is the Philippines and Indonesia, which are between the two. The export share has passed the peak, but is lower than the world average. The Philippines is a typical country with immature industrialization and even premature deindustrialization. Indonesia is the largest economy in Southeast Asia, with an economic output accounting for about 40% of ASEAN, but it is still a resource-exporting economy.

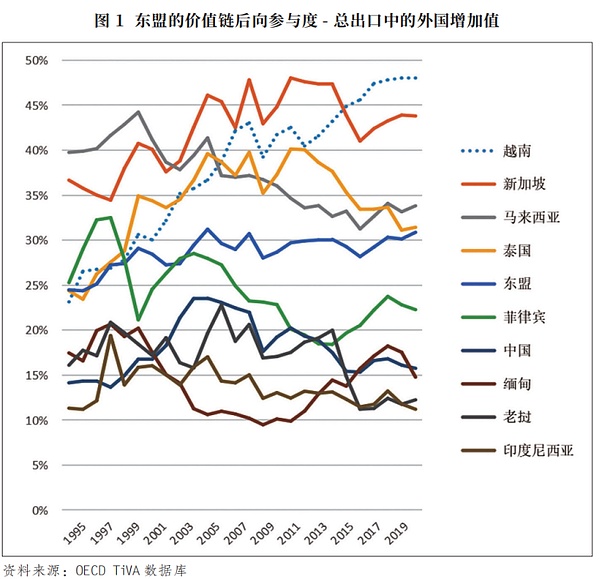

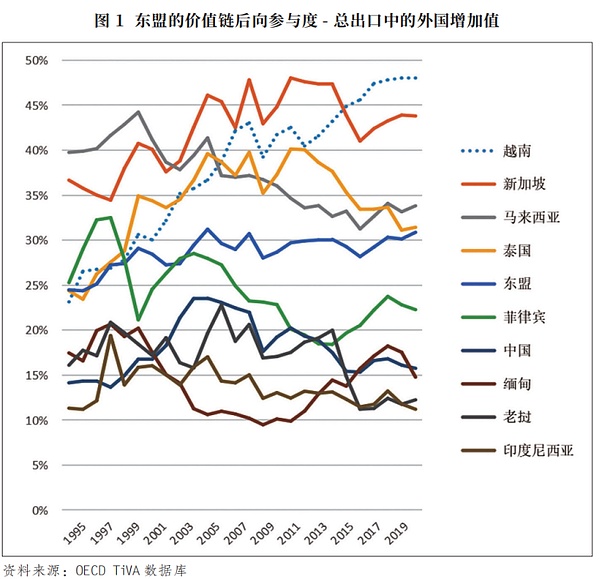

Among Southeast Asian economies, Vietnam is the most typical example of improving its development level by participating in value chain trade. After joining the WTO in January 2007, Vietnam quickly integrated into the regional production network. Among Southeast Asian countries, the foreign value added in Vietnam's exports has increased the fastest. As shown in Figure 1, after the 2008 international financial crisis, the foreign value added in the exports of other Southeast Asian economies, except Vietnam (and Myanmar to a lesser extent), has declined. In 2007, the proportion of foreign value added in Vietnam's exports exceeded 40% for the first time, and exceeded 45% in 2016, ranking first in Southeast Asia. Singapore, which ranked second, saw this proportion drop from 47% in 2014 to 41% in 2016. Compared with Vietnam and Singapore, this proportion of other Southeast Asian economies has fallen since 2018. In 2022, Vietnam's proportion exceeded 48%, reaching an unprecedented level among Southeast Asian countries, mainly because Vietnam has benefited the most from the Sino-US trade friction. In China-ASEAN trade, the proportion of China-Vietnam trade volume increased from 23.5% in 2017 to 25.2% in 2023, and the trade volume between China and Vietnam even exceeded that between China and Germany. At the same time, Vietnam's position among the United States' trading partners has risen from 17th five years ago to 7th at present. According to US statistics, Vietnam will be the third largest source of the US trade deficit in goods in 2023, reaching US$104 billion. In 2022, the United States' direct investment in Vietnam reached 3.5 billion US dollars, up 27% year-on-year.

The two industries with the most typical value-added trade paradigm are electrical machinery and general machinery trade, and Vietnam has performed very well in these two industries. Among ASEAN countries, Singapore, Thailand and Malaysia have long been the top three economies in general machinery trade. After the international financial crisis in 2008, the share of Thailand and Malaysia in ASEAN began to decline. Singapore's share had already declined before, turning to the so-called knowledge economy, focusing on branding, marketing and other links. Vietnam has continued to rise in share. In 2020, Vietnam's share in ASEAN's general machinery trade began to surpass Malaysia, ranking third in ASEAN. In the field of electrical machinery, Vietnam's share surpassed Malaysia for the first time in 2017, ranking second in Southeast Asia, second only to Singapore. Vietnam's rapid rise in these two fields also reflects the changes in its status as a trading country for mechanical products in East Asia. Vietnam's electrical machinery trading partner is mainly China, but its general machinery trading partner is mainly Japan. Traditionally, Japan is the center of the production chain in the region, and regional economic and trade relations are greatly influenced by Japan's foreign economic relations. Since the new century, after the center of the regional production chain has gradually shifted to China, the impact of changes in China's foreign economic relations on the industrial layout of Southeast Asia has also increased.

After the Sino-US trade friction in 2018, geopolitical competition has had an important impact on the regional production chain. Geopolitical competition itself has no direct connection with the value chain, but the impact of geopolitics is extensive. More than 20 years ago, globalization was at its peak, and almost all countries embraced globalization and were committed to engaging in trade on a larger scale to improve their overall welfare, and were less concerned about the distribution of trade benefits among countries. Once geopolitical competition is involved, the distribution of trade gains among countries becomes very important, and it has even changed the United States' attitude towards participating in international trade.

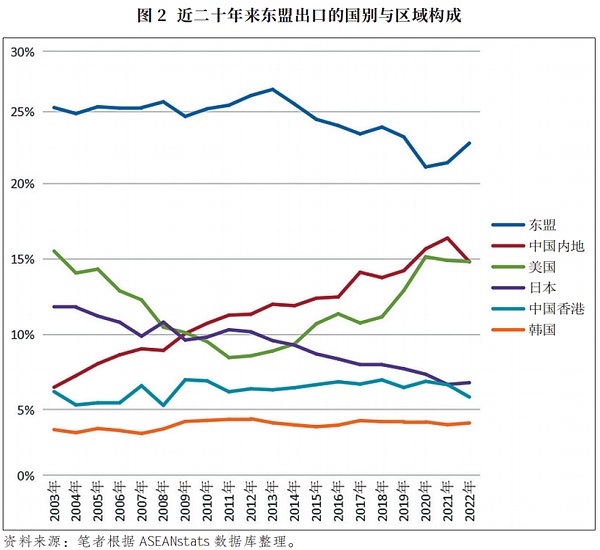

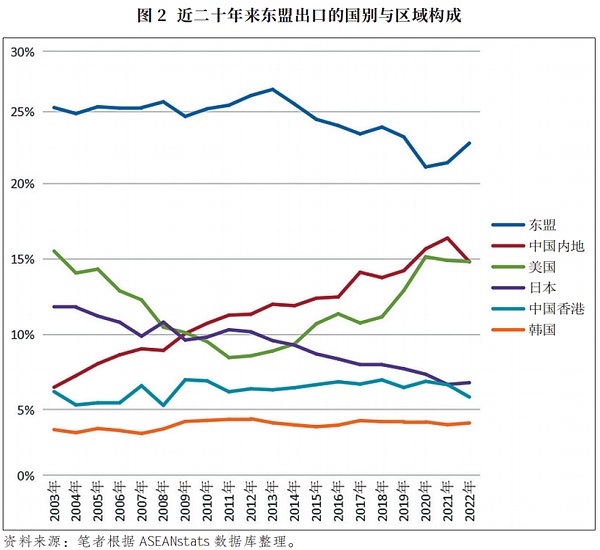

So far, the Biden administration of the United States is still implementing the tariff policy imposed by the Trump administration on China, which has affected the way ASEAN countries participate in regional production chains. As shown in Figure 2, in terms of ASEAN's participation in international trade, compared with the two stages in the early 21st century and after the 2008 international financial crisis, ASEAN's trading partners have undergone some important changes since 2018. First, the dependence on exports outside ASEAN has increased, which was less than 75% in the first two stages and rose to 77.1% in 2022. This change is surprising. It is generally believed that the increase in the proportion of intra-regional trade is a sign of increased regional autonomy. Obviously, the construction of the ASEAN Community has failed to provide itself with a larger internal market. Second, the exchange of positions between China and Japan is the biggest change in ASEAN's external trading partners in the past two decades. From the beginning of the 21st century to 2022, ASEAN's export dependence on Japan has dropped from 11.8% to 6.8%, while its export dependence on China has increased from 6.5% to 14.8%. It should be noted that compared with the early second decade of the 21st century, ASEAN's overall export dependence on China, Japan and South Korea remains unchanged at around 25%. Third, ASEAN's export dependence on the United States has shown a U-shaped trajectory of first falling and then rising over the past 20 years. It is worth noting that the biggest change in ASEAN's export market in the past decade is that the share of the US market in ASEAN's exports has increased from 8.5% to 14.8%, even 0.01 percentage points more than China's share! Among them, between 2018 and 2020, the share of the US market in ASEAN's exports soared from 11.2% to 15.7%, which shows the huge impact of Sino-US trade frictions. At present, China and the United States are ASEAN's two largest trading partners, and the trend of competition between the two powers is becoming increasingly obvious.

Since China and the United States reached the "San Francisco Vision" in November 2023, although the relationship between the two countries has eased, all parties believe that Sino-US relations are a long-term game. The impact of strategic competition between major powers on the supply chain will be long-term, and therefore it has received attention from all parties. However, from the current empirical analysis, there seems to be no consensus on the scope and extent of this impact. Judging from the data of the total trade volume between China and the United States in 2022, there is no "decoupling" between China and the United States. But from a structural point of view, the products that are less affected by tariffs are mainly toys, video game consoles, smartphones, laptops and computer monitors. The "decoupling" of the supply chain in the Sino-US confrontation has brought serious uncertainty to the cross-border industrial layout of enterprises. Although the production network of most mechanical products in East Asia is still developing actively, and the trade statistics at the departmental level do not show obvious signs of large-scale supply chain "decoupling", the industrial chain has been significantly adjusted when looking at the level of international trade sub-item data. This change is mainly due to the "decoupling" policy, especially the US entity list control measures. Although it is still unknown to what extent the prospect of "decoupling" will evolve, under the pressure of the United States, Japan, South Korea and other US allies in East Asia will also cooperate with the US control measures and reduce their investment in the region.

With the return of geopolitics, the trade model of Southeast Asia will definitely change greatly, but how it will evolve is still unclear. The economic and trade development of Southeast Asia is entering a new stage, and it is necessary to combine the first and second generation trade models to build a third generation interpretation model.

Against the backdrop of intensified Sino-US competition, Southeast Asian countries like Vietnam are benefiting, but Vietnam is also increasingly worried about being forced to choose sides. In September 2023, after US President Biden visited Vietnam, US-Vietnam relations were upgraded to a comprehensive strategic partnership. This positioning is the highest level in Vietnam's diplomacy. Previously, bilateral relations of this nature were only established with China, India, Russia and South Korea. A report released by the Australian Parliament believes that with the upgrading of US-Vietnam relations, other countries in the region are also accelerating the upgrading of bilateral relations with Vietnam, especially Japan, whose strategic partnership with Vietnam is actually a comprehensive strategic partnership that needs to be rectified. One of the most eye-catching contents of the upgrading of US-Vietnam relations is that the United States has promised to help Vietnam develop the semiconductor industry and rare earth industry, which are the areas of fierce competition between China and the United States. At the same time, the United States is also stepping up the transfer of semiconductor manufacturing in Asia back to the United States.

Another interesting example is Malaysia. Malaysia is the world's sixth largest semiconductor exporter, accounting for 13% of the global semiconductor packaging, assembly and testing market. As early as 1972, Intel, an American company, invested in the development of the semiconductor industry in Penang, Malaysia. With its mature electronic manufacturing industry and logistics advantages, Malaysia is becoming one of the biggest beneficiaries of the Sino-US semiconductor competition. Penang will attract US$12.8 billion in foreign direct investment in 2023, equivalent to the total foreign investment attracted by the state between 2013 and 2020, and most of the foreign investment comes from China. According to estimates by the local investment bureau, there are currently 55 companies from mainland China engaged in manufacturing in Penang, most of which are related to the semiconductor industry; before the US implemented the semiconductor blockade against China, there were only 16 Chinese companies in Penang.

Realism in international political economics theory usually predicts that under political pressure, the direction of economic flows will eventually follow political positions. But so far, most Southeast Asian countries have not significantly leaned towards either China or the United States. On the one hand, most Southeast Asian countries emphasize a neutral position and do not choose sides; on the other hand, the US allies in Northeast Asia are increasingly moving closer to the United States. Why can Southeast Asian countries maintain a certain generally stable situation between China and the United States? Is it because the technology level of the industries being developed in Southeast Asian countries is lower than that of Northeast Asian countries and does not touch the national security concerns of the United States? Or is it because Southeast Asia is more dependent on the Chinese market in its production network and needs to maintain a closer relationship with China to maintain its central position in ASEAN? If Southeast Asia's industries are further upgraded, will it trigger more turbulent geopolitical games? Further investigation of these issues will help us understand the development model of Southeast Asia.

Conclusion

In explaining the development of Southeast Asia, the academic community has had two major intergenerational trade models: the flying geese model based on inter-industry trade and the value-added trade model based on intra-industry trade. Currently, under the influence of strategic competition among major powers, Southeast Asia is entering the third trade form, and new political economics theories are needed to understand this trade model.

Both the flying geese trade model and the value-added trade model rely on a specific international political structure. The experience that Japanese scholars based their ideas on when proposing the flying geese model actually came from Japan's colonization of East Asia during World War II. After the end of World War II, this model was dormant for a long time. It was not until the mid-1960s when regional cooperation in Asia began that industrial transfer occurred between Asian countries in the so-called "liberal international order" led by the United States. Japanese scholars have long paid insufficient attention to the US factor. It was not until the US-Japan trade friction came to an end in the early 1990s that they began to recognize the role of the United States. Since then, globalization led by the United States has made great strides, and scholars have developed a paradigm of value-added trade to explain the rapid growth of trade. After China replaced Japan as the center of the regional production network, its impact on the development of Southeast Asia was far more important than that of Japan, which also caused greater suppression and containment from the United States.

The 2018 Sino-US trade friction was a major event that affected the industrial division of labor in Southeast Asia, and value chain trade faced great challenges. With the change of the US policy toward China, China, as the center of the regional production network, adjusted its development strategy and foreign economic relations, and the US's Asia-Pacific allies followed up on relevant policies, the development of Southeast Asia has entered the third stage. Compared with the first two stages, Southeast Asia's internal development space has shrunk, but some countries still maintain a good development trend. Vietnam is a typical representative of seeking development under the game of great powers. Although it is still impossible to conclude that China and the United States are decoupling, the structure of intra-regional trade is undergoing great changes. From 2018 to 2020, the proportion of the US market in ASEAN exports soared from 11.2% to 15.7%, and the proportion of the Chinese market in ASEAN exports rose from 13.8% to 15.8%. In terms of growth rate, the United States is half ahead of China. Moreover, the increase in the United States' share began as early as the "return to Southeast Asia" in the first term of the Obama administration and the "pivot to Asia" in 2011. It can be seen that the new trade model has begun to take shape during the heyday of the old model. The impact of geopolitics and policies on trade flows is far-reaching. It remains to be seen whether China and the United States can maintain the status of ASEAN's largest partner for a long time.

It should be noted that between 2018 and 2020, the proportion of the ASEAN market in ASEAN exports fell from 24.0% to 21.3%. After the epidemic, the proportion of the ASEAN regional market has recovered, but it has not yet reached the level of 2018. This proves that the construction of the ASEAN internal market has been greatly impacted by geopolitics. The good news for China is that China continues to adhere to an open policy and stabilizes China-ASEAN economic and trade relations, especially imports from ASEAN are still growing. This shows to a certain extent that China has a lot of room for adjustment with its super-large market. As long as it adheres to an open and inclusive free trade policy, it can still greatly delay or even avoid the separation and "decoupling" of economic and trade relations in East Asia. But it cannot be ignored that the United States is vigorously supporting countries with better conditions among Southeast Asian economies, trying to replace China's position in the East Asian production chain from both high and low directions.

Anais

Anais