Author: Decentralised.Co; Translation: Golden Finance xiaozou

As an asset class, venture capital has always followed an extreme power law distribution. But because we are always tired of chasing the latest narrative, the specific extent of this distribution has never been deeply studied. In the past few weeks, we have developed an internal tool to track the network relationships of all crypto venture capital institutions. Why do this?

The core logic is simple: as an entrepreneur, knowing which venture capital institutions often co-invest can save time and optimize financing strategies. Each transaction is a unique fingerprint, and when we visualize this data, we can interpret the story behind it.

In other words, we can track the key nodes that dominate most of the financing activities in the crypto field. It is like finding hub ports in modern trade networks, which is essentially the same as merchants finding trading bases thousands of years ago.

We did this experiment for two reasons:

First, we run a VC network that’s like “Fight Club”—no one’s throwing punches yet, but we rarely discuss it publicly. This network covers about 80 funds, while there are only 240 institutions in the entire crypto VC field that invest more than $500,000 at the seed stage. This means that we directly reach one-third of market participants, and nearly two-thirds of practitioners read our content. This influence is far beyond expectations.

However, it has always been difficult to track the actual flow of funds. Sending project progress to all funds will create information noise. This tracking tool came into being. It can accurately screen which funds have invested, which tracks they have laid out, and who their partners are.

In addition, for entrepreneurs, understanding the flow of funds is only the first step. What is more valuable is to understand the historical performance of these funds and their usual co-investors. To do this, we calculated the historical probability of a fund’s investments receiving follow-on financing—but this data is distorted in later rounds (such as Series B) because projects often choose to issue tokens rather than traditional equity financing.

Helping entrepreneurs identify active investors is only the first stage. The next step is to figure out which sources of capital are truly advantageous. With this data, we can analyze which funds’ co-investments will produce the best results. This is certainly not rocket science. Just like no one can guarantee marriage on a first date, no VC can guarantee a project will enter Series A with just a check. But knowing the rules of the game in advance is just as important for fundraising as it is for dating.

1. Successful Architecture

We use basic logic to select funds with the highest follow-on financing rates in their portfolios. If multiple projects invested by a fund can obtain new financing after the seed round, it means that its investment strategy is indeed unique. When the invested enterprise completes the next round of financing at a higher valuation, the venture capital's book return will also increase, so the subsequent financing rate is a reliable indicator of fund performance.

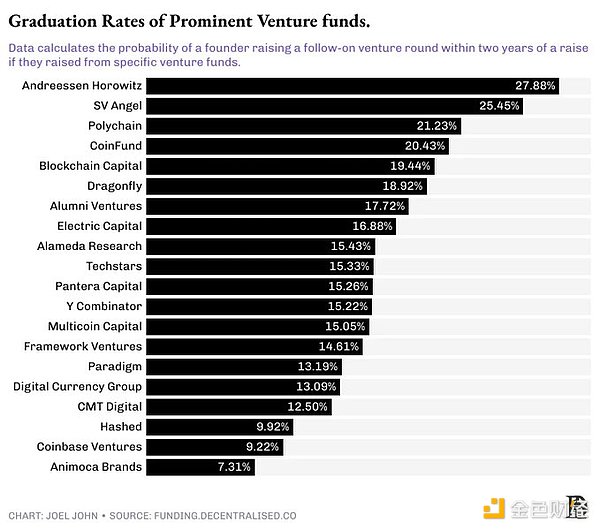

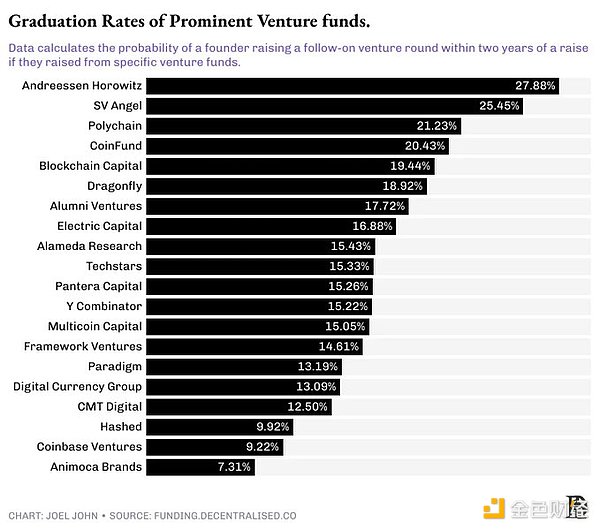

We selected the 20 funds with the largest number of subsequent financings in their portfolios and counted their total investment cases in the seed stage. From this, we can calculate the probability percentage of entrepreneurs obtaining subsequent financing. For example, if a fund invests in 100 seed projects, 30 of which obtain new financing within two years, its "graduation rate" is 30%.

It should be noted that we strictly limit the observation period to two years. Many startups may choose not to raise funds, or raise funds at a later stage.

Even among the top 20 funds, the power law effect is still amazing. For example, the probability of a16z-invested projects obtaining follow-up financing within two years is 1/3 - that is, one out of every three a16z-invested startups can enter the A round. Considering that the probability of the last-ranked funds is only 1/16, this result is quite impressive.

The follow-up financing rate of the investment portfolio of funds ranked close to 20 on this list is about 7%. These numbers may seem close, but let’s look at them in detail: a 1/3 probability is equivalent to rolling a dice with a number less than 3, while a 1/14 probability is comparable to giving birth to twins—these are completely different results.

Jokes aside, the data truly reveals the clustering effect in the crypto venture capital field. Some funds can proactively design follow-up financing for invested projects because they also operate growth funds. Such institutions participate in both seed rounds and follow-up A rounds. When venture capital continues to invest in the same project, it usually sends positive signals to investors in subsequent rounds. In other words, whether a venture capital institution has a growth fund will significantly affect the future success probability of the invested company.

The ultimate form of this model will be that crypto venture capital gradually evolves into private equity investment in mature revenue-generating projects.

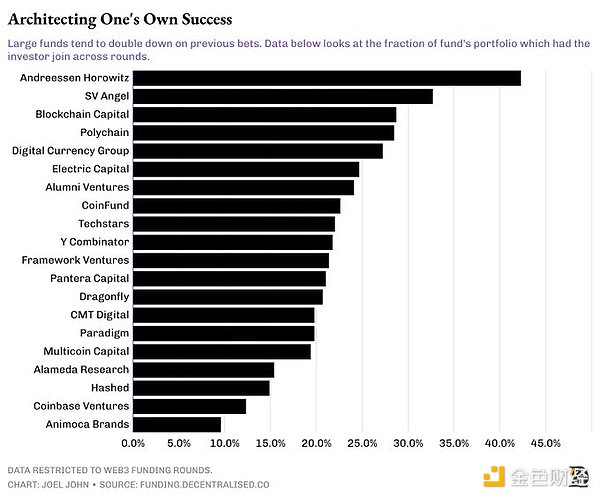

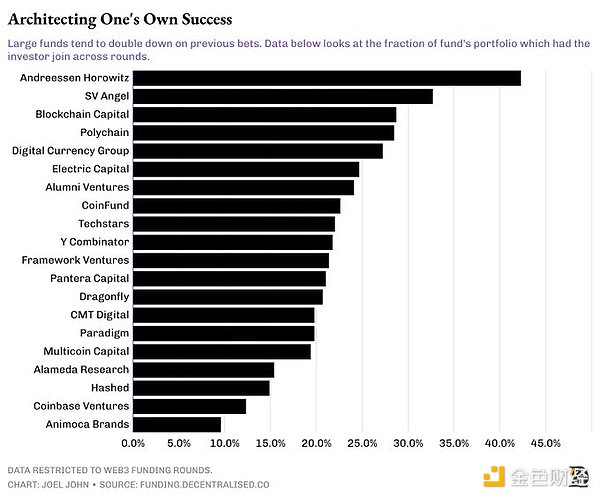

We have theoretically deduced this transformation. But what does the data reveal? To explore this question, we counted the number of startups in our portfolio that received follow-on funding and calculated the probability that the same VC firm participated in the follow-on round.

That is, if a company received seed funding from a16z, what is the probability that a16z will participate in its Series A funding?

The pattern soon emerged: large funds with a management scale of more than $1 billion tend to follow up more frequently. For example: 44% of the projects in a16z's portfolio that received follow-on funding have continued to follow up with it; Blockchain Capital, DCG, and Polychain will make additional investments in 25% of the projects that received follow-on funding.

This means: The selection of investors in the seed round or pre-seed round is far more important than imagined, because these institutions have a significant "repeated investment preference".

2. Inertial co-investment

These rules are post-mortems. We are not implying that projects that are not favored by top venture capital are doomed to fail - the essence of all economic behavior is growth or profitability, and companies that achieve either goal will eventually be revalued. But if you can increase the probability of success, why not? If you can't get direct investment from the top 20 funds, it is still a viable strategy to reach capital hubs through their networks.

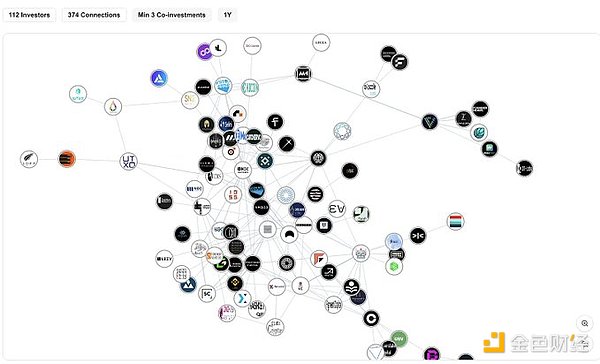

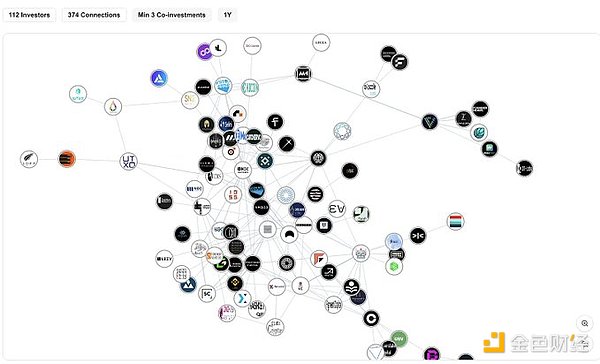

The figure below shows the network map of all venture capital institutions in the crypto field in the past decade: 1,000 investment institutions are connected through about 22,000 co-investments. On the surface, there seem to be many choices, but it should be noted that this includes funds that have ceased operations, have not achieved returns, or have suspended investment. The real market structure is clearer in the figure below: there are only about 50 funds that can make a single A-round investment of more than US$2 million; the investment network participating in such rounds covers about 112 institutions; these funds are accelerating their integration, showing a strong preference for specific co-investment.

Over time, funds appear to develop a steady habit of co-investing. That is, funds investing in one entity tend to attract peer funds because of complementary skills (such as technology assessment/market development) or based on partnerships. To study how these relationships work, we began exploring the pattern of co-investment between funds last year.

By analyzing the co-investment data of the past year, we can see that:

Polychain and Nomad Capital co-invested 9 times;

Bankless and Robot Ventures co-invested 9 times;

Binance co-invested with Polychain and HackVC 7 times each;

OKX and Animoca co-invested 7 times.

Top funds are becoming increasingly strict in selecting co-investors:

Paradigm co-invested with Robot Ventures in 3 of its 10 investments last year;

DragonFly co-invested with Robot Ventures and Founders Fund 3 times in 13 investments;

Founders Fund co-invested with Dragonfly in 3 of its 9 investments.

This shows that the market is turning to "oligopoly investment" - a few funds are betting with larger chips, and the co-investors are mostly old and well-known institutions.

3. Matrix Analysis

Another way of research is through the behavioral matrix of the most active investors. The above figure shows the network of funds with the highest investment frequency since 2020. It can be seen that: Accelerators are unique. Although accelerators such as Y Combinator invest frequently, they rarely invest in conjunction with exchanges or large funds.

On the other hand, you will find that exchanges also generally have specific preferences. For example, OKX Ventures has a high-frequency co-investment relationship with Animoca Brands, Coinbase Ventures has co-invested with Polychain more than 30 times, and has also co-invested with Pantera 24 times.

The structural patterns we observed can be summarized into three points:

* Accelerators tend to rarely co-invest with exchanges or large funds, despite their high investment frequency. This may be due to stage preferences.

* Large exchanges tend to have a strong preference for venture funds in the growth stage. Currently, Pantera and Polychain dominate in this regard.

* Exchanges tend to work with local institutions. The different preferences of OKX Ventures and Coinbase for co-investment targets highlight the global nature of capital allocation in the Web3 era.

Now that venture capital is converging, where will marginal capital come from? An interesting phenomenon is that corporate capital is a self-contained system: Goldman Sachs has only co-invested with PayPal Ventures and Kraken twice in history, while Coinbase Ventures has co-invested with Polychain 37 times, Pantera 32 times, and Electric Capital 24 times.

Unlike traditional venture capital, corporate capital usually targets growth-stage projects with product-market fit. At a time when early-stage financing is shrinking, the behavior patterns of this type of capital are worth continuing to observe.

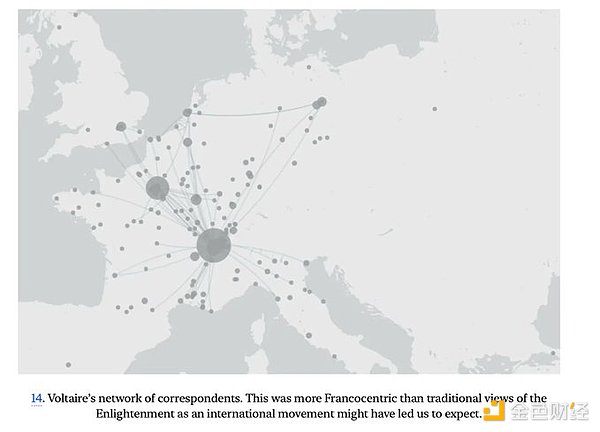

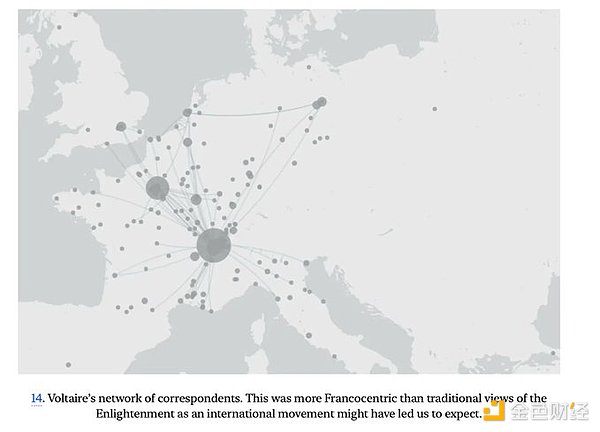

4. Dynamically evolving capital networks

After reading Niall Ferguson's "The Square and the Tower" a few years ago, I had the idea of studying the relationship network in the crypto field. The book reveals that the spread of ideas, products and even diseases is related to network structure, but it was not until we developed the financing data dashboard that we truly realized the visualization of the crypto capital network.

Such data sets can be used to design (and execute) mergers and acquisitions and token privatization plans - this is the direction we are exploring internally, and can also assist in business cooperation decisions. We are working on opening data access to specific institutions.

Back to the core question: Do network relationships really improve fund performance? The answer is quite complicated.

The core competitiveness of funds increasingly depends on the ability of the screening team and the scale of funds, rather than simply the network resources. But the personal relationship between the general partner (GP) and the co-investor is indeed key - the shared project flow of venture capital is based on interpersonal trust rather than institutional brand. When a partner changes jobs, his network of relationships will naturally migrate to the new employer.

A study in 2024 verified this hypothesis. The paper analyzed 38,000 investment rounds of 100 top VCs and came to the key conclusion:

* Historical co-investment does not guarantee future cooperation, and failed cases will interrupt trust between institutions.

*Joint investments surge during the frenzy, and funds rely more on social signals than due diligence during the bull market; they tend to go it alone in the bear market, and funds tend to invest independently when valuations are low.

*Capability complementarity principle: Homogeneous investors often gather together to indicate risk.

As mentioned earlier, in the end, joint investments do not occur at the fund level, but at the partner level. In my own career, I have seen some people jump between different organizations. The goal is usually to work with the same person, regardless of what fund they join. In an era where artificial intelligence replaces manpower, interpersonal relationships remain the foundation of early-stage venture capital.

There are still many gaps in this study of crypto venture capital networks. For example, the liquidity allocation preferences of hedge funds, how growth-stage investments adapt to market cycles, and the intervention mechanisms of mergers and acquisitions and private equity. The answer may be hidden in the existing data, but it will take time to refine the right questions.

Hui Xin

Hui Xin