Written by: 0xjs@Golden Finance

Deepseek, a technological breakthrough of "national destiny level", has a subsequent impact that continues to ferment, and the entire Chinese assets may need to be revalued.

On February 5, 2025, Deutsche Bank published a research report "China eats the World", which swept the screen among investors. Deutsche Bank said that 2025 is the year when China surpasses other countries. In 2025, China launched the world's first sixth-generation fighter and low-cost artificial intelligence system "DeepSeek" within a week. Marc Andreessens called the launch of "DeepSeek" the "Sputnik moment" of AI, but it is more like China's "Sputnik moment", marking the recognition of Chinese intellectual property rights. China's areas of excellence in high value-added fields and dominating supply chains are expanding at an unprecedented rate. China has companies that occupy a leading position in almost every industry. As Chinese companies expand in the global market, China's valuation discount should turn into a premium at some point in the future. Investors must shift significantly to investing in Chinese stocks in the medium term, and Hong Kong/China stocks will usher in a big bull market in the medium term.

It is worth noting that the title of the research report borrowed the famous saying of Marc Andreessens, founder of a16z: "Software is eating the world", and the first part of the research report "This is China's, not AI's, 'Sputnik moment'" also borrowed Marc Andreessens' recent comments on DeepSeek: "DeepSeek is AI's Sputnik moment".

The following is the full text of Deutsche Bank's research report:

Original title: China eats the World

Author: Peter Milliken, CFA, research analyst

This is China's, not AI's, "Sputnik moment"

We believe that 2025 is the year when the investment community realizes that China is surpassing the rest of the world. It is increasingly difficult to ignore the fact that Chinese companies are offering better value for money and often better quality in many manufacturing sectors and, increasingly, even in services.

Investors pay for dominance, and we expect the “China discount” to disappear. Moreover, with policies favoring consumption over production and likely due to financial liberalization, we believe profitability is expected to exceed expectations through the cycle. We believe the bull run in Hong Kong/China equities began in 2024 and will exceed previous highs in the medium term.

China first emerged as a dominant player in global apparel, textiles, and toys. It then dominated in basic electronics, steel, shipbuilding, and more recently in white goods, solar, and other less visible sectors.

China has also, without warning, dominated in industries such as complex telecommunications equipment, nuclear power, defense, and high-speed rail. These technological achievements were previously unappreciated by investors.

But by late 2024, China is in the spotlight for its rapid rise as the world’s leading auto exporter, flooding the global market with electric vehicles that are advanced, attractive, and cheaper than existing models.

In 2025, China launches the world’s first sixth-generation fighter jet and a low-cost artificial intelligence system, DeepSeek, in a week.

Marc Andreessens calls the launch of DeepSeek a “Sputnik moment” for AI, but it’s more like China’s “Sputnik moment,” marking the recognition of Chinese intellectual property. China’s areas of excellence in high value-added sectors and dominating supply chains are expanding at an unprecedented pace.

We believe that global investors tend to significantly underweight Chinese assets, just as they avoided fossil fuels a few years ago, until the market punishes investors for making non-market-oriented decisions. We see minimal exposure to China today. Investors who like leading companies with moats cannot ignore this: it is Chinese companies, not the Western companies they see as economically superior, that have the widest and deepest moats today.

China’s manufacturing prowess is clear, with twice as many goods exports as the United States. China contributes 30% of global manufacturing value added, and its share of services is rising rapidly. China has been shunned as an investment destination due to concerns about its economic weakness, but despite a cyclical slowdown, it is still growing more than twice as fast as most developed markets.

With companies that lead in nearly every industry, it is unlikely that China’s share of global market capitalization will remain in the single digits for long. We believe there is a growing recognition that China today is where Japan was in the early 1980s, when Japanese companies were climbing the value chain, producing higher quality products and emerging with innovation. Many Western companies and industries may face a potential existential crisis and therefore need to recalibrate their portfolios to reflect this.

To survive, Western companies will need to: 1) automate at scale; and/or 2) erect trade barriers. The second path has historically been a downhill climb for economies, and while that is happening, it will not necessarily help the West. In the automotive sector, for example, China’s main export markets tend to be the roughly 7 billion people outside the G10 countries.

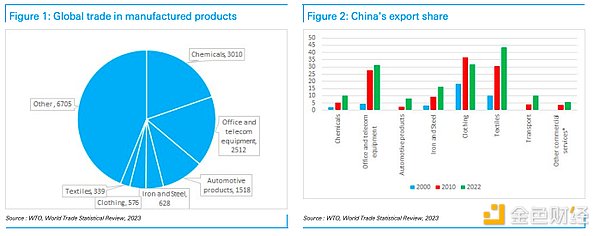

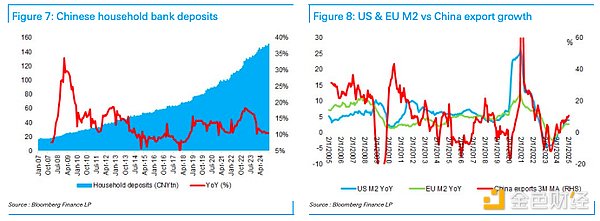

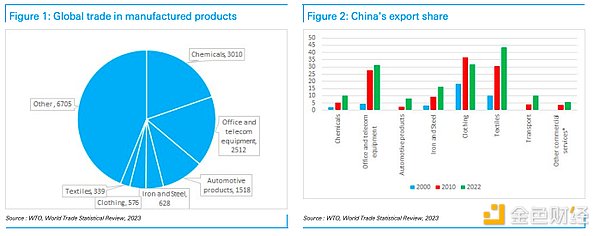

Figure 1: Global Trade in Manufactured Goods Figure 2: China’s Export Share

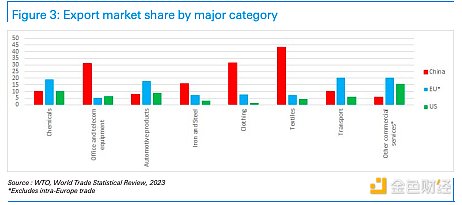

Looking at the major categories of international trade, China is gaining share in all but apparel (a sector it dominated before expanding its operations overseas). China is larger than the United States in key commodity categories, and often many times larger. The only exception is cars (in value terms, not volume), but China is probably ahead there too - Ford's CEO drives a Xiaomi, and it's hard to see that changing.Even in services, China is catching up, with transport services for example increasing share by about 0.5 percentage points per year.

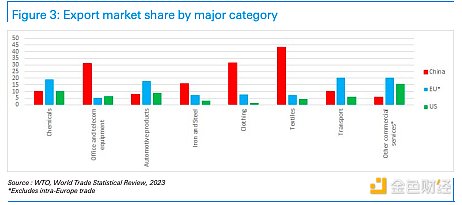

Figure 3: Export market share by major categories

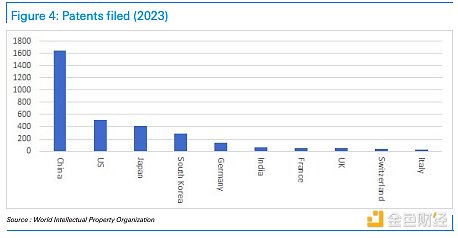

Using patents as a proxy for IP

China has a complete value chain and has formed local professional clusters, with multiple Silicon Valley-like areas of expertise in key industries, and works closely with domestic universities on research.

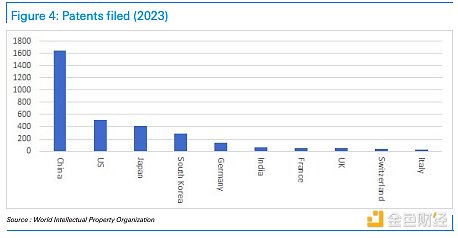

In electric vehicles, China holds about 70% of patents, and is in a similar position in 5G and 6G telecommunications equipment.

In 2023, China will account for nearly half of global patent applications. This trend is likely to continue, as China has more science and engineering graduates than the rest of the world combined, excluding India. In addition, consider that many graduates in other countries are also Chinese. Therefore, unless extraordinary circumstances occur, the rise of Chinese companies' dominance is unlikely to be stopped in the short term.

China does face trade barriers, with US and EU tariffs on electric vehicles being an obvious example, but the West is constrained in taking action because they need to consider the more serious consequences that may arise (such as inflation, reduced competitiveness, and retaliation). In the 1980s, the United States tried to curb Japan's development with some success, but we think China's situation today is not like Japan in 1989, but more like Japan in the years before.

Figure 4: Number of patent applications in 2023

China vs. Japan in the 1980s

Throughout the 1970s, Japan’s gross national product (GNP) ranked second in the world, second only to the United States. After checking Wikipedia, we were surprised to find that Japan’s real GDP growth rate in the 1980s was only 4% per year, but this was still regarded as an important part of its economic “miracle”. By contrast, today’s anxiety about whether China’s economic growth is 4% or 5% and that it is “slow” may evolve to seeing it as a “miracle” in hindsight.

The Plaza Accord required a 40% appreciation of the yen, which slowed Japan’s industrial lead. This led to a slowdown, which the Japanese government responded with loose monetary policy. Growth recovered to 5% in 1987-1989, a period of strong stock market gains and bubbles. The recovery in growth led to a recovery in the steel and construction industries, raising wages and increasing employment. In the late 1980s, domestic demand, rather than exports, became the driver of economic growth. This may also happen in China.

Japan in the 1980s

According to Wikipedia, Japan’s economic growth was achieved through the input of a large number of cheap labor, intensive use of capital, and productivity increases. Domestic investment accounted for more than 30% of GDP, and financial repression kept interest rates low, which promoted investment. Japan acquired new technologies through joint ventures. Japan's savings rate was 40% of GDP in the early 1970s, but fell to nearly 30% in the early 1980s. In the 1970s, Japan began to set up factories overseas to avoid trade frictions. China has only recently begun to take similar measures.

The question is: where is China on this path? Like Japan, China has experienced a real estate bubble, but not to the same extent. Moreover, it has been six years since credit tightened and the real estate downturn began. House prices have fallen by a third, mortgage rates have fallen by half, and nominal GDP has increased by about a third, so housing affordability has returned to levels not seen in many years. Stock market valuations are also low due to low profit margins and low price-to-earnings multiples. So this is not Japan in the bubble of 1989, when the value of Japanese stocks had increased 50 times in the previous 20 years.

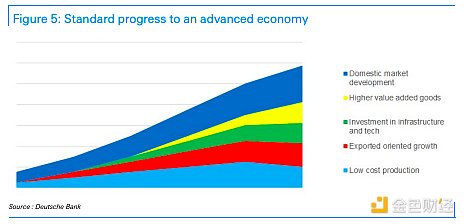

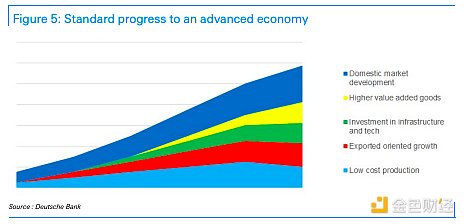

The common view is that China will not follow Japan's consumption-led economic development path, but will only fall into an economic downturn like Japan. But in fact, China is on a path that has been taken by the United States, Japan, Singapore, Hong Kong, Taiwan, South Korea, Spain, and many countries and regions in Eastern Europe. Unlike some other countries and regions struggling in the middle-income trap, China has become a global leader in manufacturing and an increasing number of service industries.

Figure 5: Standard progression toward a developed economy

Japan liberalized its financial system around this time

In Chapter 12 of the IMF’s 2013 report, China’s Economic Transformation, it is mentioned that Japan in the 1980s had similarities to China’s future development path. Prior to the Plaza Accord, Japan’s financial system was highly regulated, interest rates were regulated, capital controls were strict, and demand for bank credit was limited due to ample corporate capital. Japanese investors’ large holdings of U.S. assets, combined with a weaker yen, have led to calls for Japan to open up its financial markets and make yen-denominated assets more attractive. This, in turn, has led to capital inflows into Japan and an increase in the money supply, which has fueled economic growth and asset bubbles.

China may be heading in a similar direction. President Trump may follow President Reagan’s lead in pushing for Chinese financial liberalization in a trade deal, and China may also be ready to accelerate the internationalization of the renminbi. We think this is positive for stocks because the renminbi is likely to depreciate, which would improve corporate profitability and the attractiveness of Chinese assets from a foreign exchange perspective. Why would the U.S. push for this? Reasons could include: 1) political considerations to reach a deal; 2) the belief that a weaker renminbi would offset the impact of tariffs, allowing trade to continue and impose tariffs rather than crowding out trade; 3) the belief that financial liberalization would cause the renminbi to appreciate, making China less competitive.

Regardless of external pressures, if China wants to boost consumption, liberalizing the financial system will help, by normalizing interest rates and ending the wealth transfer from savers to businesses. This will reduce overinvestment and cutthroat competition as capital will be properly allocated, which will help improve corporate profitability and ease fiscal pressures as returns on state-owned enterprises will improve. We expect large businesses, investment companies and households to increasingly pressure the government to ease cutthroat competition to boost stock market value. Just as the government previously slowed overinvestment in infrastructure and real estate, curbing overinvestment in industry is the obvious next step, and it may come sooner than expected. We expect this to be a key topic in 2025, both to appease the United States and as the situation requires, and we expect it to drive a major bull market.

But what about China's declining population?

China's declining population is a drag on economic growth, but many countries face this problem. We think this completely overlooks an important fact, which is that China has two advantages: 1) it is a leader in automation, with about 70% of the world's industrial robots installed in China, which brings productivity advantages and thus increases per capita wealth; and 2) it has a huge potential market, which is expanded by the "One Belt, One Road" initiative that includes Central Asia, West Asia, the Middle East and North Africa in its development track.

Central Asia has a population of only 80 million but is rich in resources; West Asia has a population of 310 million and is generally wealthy. South Asia has a population of 2.1 billion (although two-thirds of them are in India, which currently largely restricts trade and investment with China, but this may change in the medium term). And then there is Africa, with a population of 1.4 billion. In other words, Africa has a potential consumer population of about the same size as China, and Central Asia, West Asia and South Asia (excluding India) have a potential consumer population of about the same size as ASEAN plus Latin America, and India will also become a huge market if Sino-Indian relations improve. Therefore, focusing only on China's domestic population may lead to incorrect conclusions about China's future.

In 2024, China's exports grew by 7%, with exports to Brazil, the UAE and Saudi Arabia growing by 23%, 19% and 18% respectively, and exports to ASEAN countries along the Belt and Road Initiative growing by 13%. At present, China's exports to ASEAN plus BRICS+ are equivalent to those to the United States plus the European Union, and its export market share to these destinations has increased by nearly two percentage points each year over the past five years. Even in Latin America, China is rapidly expanding its market. Therefore, although the high US tariffs will hurt China, Deutsche Bank's economic team believes that if the United States imposes 10% tariffs in the first half and the second half, respectively, it will put 0.5% downward pressure on China's GDP, which is a manageable shock, given that US exports account for 3% of China's GDP.

The downside of China's export dominance is that many major countries in the world have adopted protectionist measures even within the BRICS+, so China's export growth is somewhat limited. However, due to their advantages in intellectual property and manufacturing value-added, Chinese companies are likely to expand their influence in international markets by setting up factories in other markets or exporting parts for assembly. The weaponization of the dollar makes investing in overseas infrastructure and factories more attractive than investing in US Treasuries, so the future direction of development is quite clear.

Figure 6: China expands new economic market (unit: million people)

Figure 6: China expands new economic market (unit: million people)

US-China trade issues may usher in unexpected benefits

The market generally expects the US tariff level on China to be higher than Deutsche Bank's expectations (we expect a 20% tariff to be implemented in two steps in 2025, one of which has already been announced). But the reality may be much more optimistic than this pessimistic expectation.

The Trump administration is clearly keen on tariffs as a source of fiscal revenue, and China is seen as a major source of tariff revenue for economic and strategic reasons. However, President Trump seems to value tactical wins more, perhaps more than ideological positions that are difficult to support. In our industry, there are investors and traders. In recent years, the influence of traders has been increasing. Perhaps President Trump is more of a political "trader" than an ideological "investor". If so, expect him to set strict stop-loss points.

The emergence of "DeepSeek" has shattered the Western fantasy that it can contain China. The United States would be better off stimulating business development by reducing regulations, providing cheap energy, and lowering import barriers for intermediate products that cannot be produced domestically. The last point may take longer to come to fruition, but we expect internal pressure from members of the U.S. House of Representatives and Senate, as well as business leaders, to return the U.S. to traditional Republican positions on trade. This may require some back-and-forth, but we expect a more pro-trade stance to eventually become part of an “America First” agenda before the midterm elections.

We believe a political “trader” would seek to lock in an early outcome, so a U.S.-China trade deal could be reached in the first half of 2025, and then focus would turn to Western Hemisphere affairs. A quick deal could include limited tariffs (as Deutsche Bank expects), the removal of some existing restrictions, and some large contracts between Chinese and American companies. If this happens (and we think it will), expect Chinese stocks to rise.

Trade and stock market are not closely correlated

Historically, trade and economic strength have always been mutually reinforcing. Therefore, we were surprised to find that there is little research linking exports to stock market performance. However, China’s exports are closely tied to global money supply growth, which has been rising but is now slowing. When we prompted Deutsche Bank’s AI platform to look for relevant research, it told us: “Some studies suggest that export growth can boost corporate earnings and therefore stock valuations… [but] some studies also suggest that a singular focus on export growth can sometimes come at the expense of domestic demand, which can hamper overall economic growth and thus have a negative impact on the stock market.”

So, paradoxically, falling exports could actually drive stocks higher for a while. China’s rise across industries has been accompanied by overinvestment in many areas. In solar, efforts are underway to cut supply, which could be bullish for stocks if other sectors follow suit, potentially freeing up some money for domestic consumption.

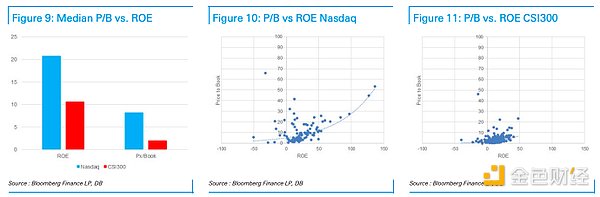

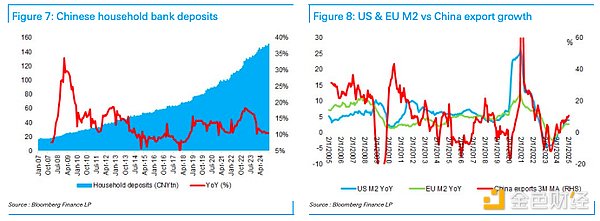

China’s household deposit growth has slowed to twice the rate of nominal GDP growth, but since 2020, Chinese household savings have increased by $10 trillion, and we expect these savings to be heavily used for consumption and investment in the stock market in the medium term. Therefore, Hong Kong/China stocks have a lot of room to rise on accelerating earnings growth and a re-rating of P/E ratios.

Figure 7: Chinese household bank deposits Figure 8: US and EU M2 and China's export growth comparison

Valuing market leaders

Figure 7: Chinese household bank deposits Figure 8: US and EU M2 and China's export growth comparison

Valuing market leaders

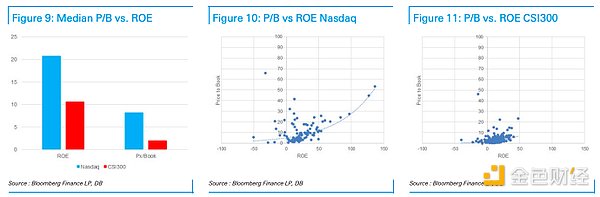

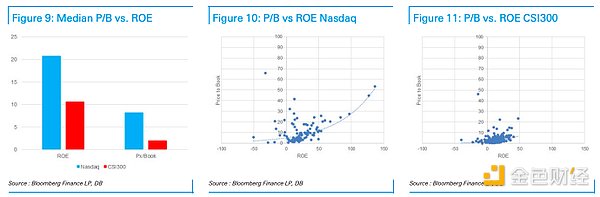

As Chinese companies expand in global markets, it seems likely that this valuation discount should turn into a premium at some point in the future. We believe that investors will have to make a significant shift towards Chinese stocks in the medium term and that it may be difficult to acquire these stocks without pushing up share prices. We have been bullish on Chinese stocks but have been struggling to find the catalyst that would wake up the world and buy into Chinese stocks, and we think China’s “Sputnik moment” (or something like dominance in electric vehicles) is that catalyst. We expect Hong Kong/China stocks to continue to lead in the medium term, as they did in 2024. Figure 12: Comparison of expected P/E ratios of MSCI China Index and MSCI World Index

Figure 12: Comparison of expected P/E ratios of MSCI China Index and MSCI World Index

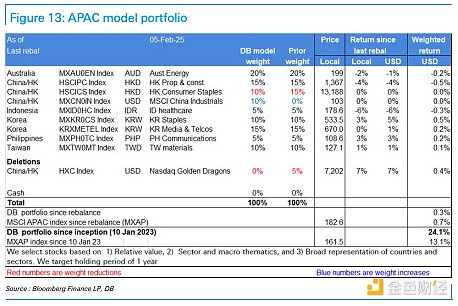

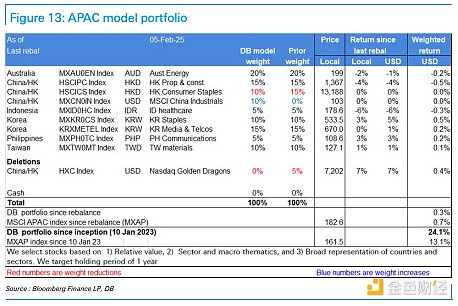

14px;">Figure 13: Asia Pacific Portfolio Model

Miyuki

Miyuki