Translated by: Babywhale, Techub News

At 22:00 Hong Kong time on the 23rd, Federal Reserve Chairman Powell delivered an important speech on the US economy and the Federal Reserve's monetary policy at the Jackson Hole Global Central Bank Annual Meeting. At the meeting, Powell gave the clearest signal of interest rate cuts this year. The September interest rate cut is almost a foregone conclusion. The key is the extent of the interest rate cut.

During Powell's speech, Bitcoin experienced a sharp fluctuation of "first rise, then fall, and then rise again", and successfully stood at $64,000 in the early hours of Friday.

There are two voices in the current market. One believes that the end of the tightening cycle heralds the start of a new round of bull market; the other believes that based on past experience, interest rate cuts are the beginning of a decline. Since Bitcoin broke through $70,000 at the beginning of the year, it has been trading sideways near the high point of the last bull market for nearly half a year. The subsequent trend, whether it is rising or falling, means that one of the long and short sides has surrendered completely.

Will the future trend be a simple "interest rate cut means rise" or will it repeat history again? The previous revision of non-farm payrolls by more than 800,000 people and the interest rate cut came at the same time. Is it really a soft landing or is the economy facing a crisis? Perhaps we can find clues from Powell's words:

The following is the full text of Powell's speech:

Four and a half years after the outbreak of the new crown epidemic, the severe economic distortions caused by the epidemic are fading and inflation has dropped sharply. The labor market is no longer overheated, and the current situation is not as tight as before the epidemic. Supply constraints have normalized. The balance of risks to our twin missions—controlling inflation while balancing employment—has shifted. Our goal is to restore price stability while maintaining a strong labor market and avoid the sharp rise in unemployment that characterizes early deflation when inflation expectations are less firmly anchored. While the task is not yet complete, we have made considerable progress toward that outcome.

Today, I will begin by talking about the current economic situation and the future path for monetary policy. I will then discuss economic events since the outbreak of the pandemic, exploring why inflation has risen to levels not seen in a generation and why inflation has fallen sharply while unemployment has remained low.

Near-Term Policy Outlook

Let’s start with the current situation and the near-term policy outlook.

For much of the past three years, inflation has been well above our 2 percent objective, and labor market conditions have been extremely tight. The Federal Open Market Committee's (FOMC) priority is, of course, to reduce inflation. Most contemporary Americans have not experienced the pain of prolonged high inflation. Inflation has caused significant hardship, especially for those who cannot afford the high costs of basic necessities such as food, housing, and transportation. The stress and sense of unfairness that high inflation has caused persists today.

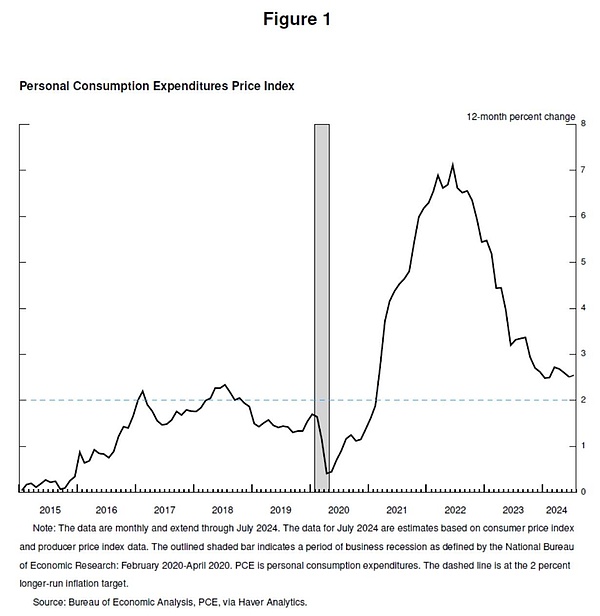

Our restrictive monetary policy has helped to restore balance between aggregate supply and demand, mitigate inflationary pressures, and ensure that inflation expectations remain well anchored. Inflation is now closer to our objective, with prices rising 2.5 percent over the past 12 months (Figure 1). Following a brief pause in the decline in inflation at the beginning of the year, we have made further progress toward our 2 percent objective. I am increasingly confident that inflation is on a sustainable path back to 2 percent.

Speaking of jobs, in the years before the pandemic, we saw the benefits of long-term strong labor market conditions: low unemployment, high participation rates, historically low racial employment gaps, as well as low and stable inflation, healthy real wage growth, and increasing concentration among low-income people.

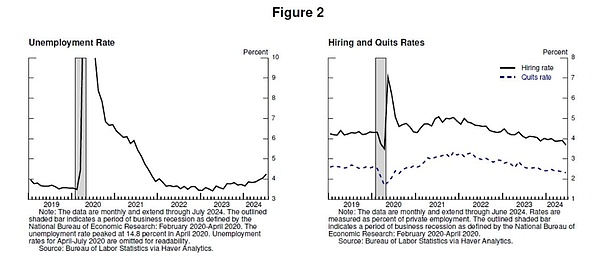

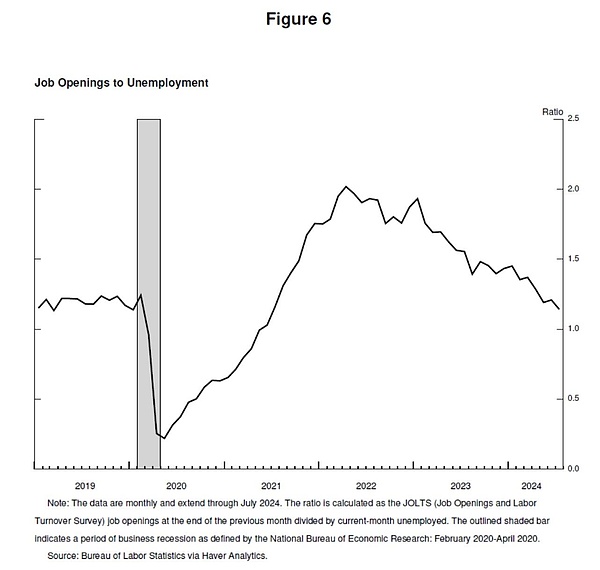

Today, the labor market has cooled significantly from its previous overheated state. The unemployment rate began to rise more than a year ago and is now 4.3%, still low by historical standards but nearly a full percentage point above its level at the beginning of 2023 (Figure 2). Most of the increase has occurred in the past six months. So far, the increase in unemployment has not been driven by layoffs caused by the recession. Instead, the increase primarily reflects a large increase in the supply of workers and a slowdown in the previously frenetic pace of hiring. Even so, the cooling of labor market conditions is unmistakable. Job growth has remained solid but has slowed this year. Job openings have fallen, and the ratio of job openings to unemployment has returned to pre-pandemic levels. Hiring and quit rates are now below their levels in 2018 and 2019. Nominal wage growth has slowed. All in all, labor market conditions are less tight now than they were before the pandemic in 2019, when inflation was below 2%. It seems unlikely that the labor market will be a source of rising inflationary pressures any time soon. We do not seek or welcome a further cooling of labor market conditions.

Overall, the economy continues to grow at a solid pace. But inflation and labor market data suggest a changing landscape. Upside risks to inflation have receded. Downside risks to employment have increased. As we emphasized at our last FOMC meeting, we are mindful of risks to our dual mandate.

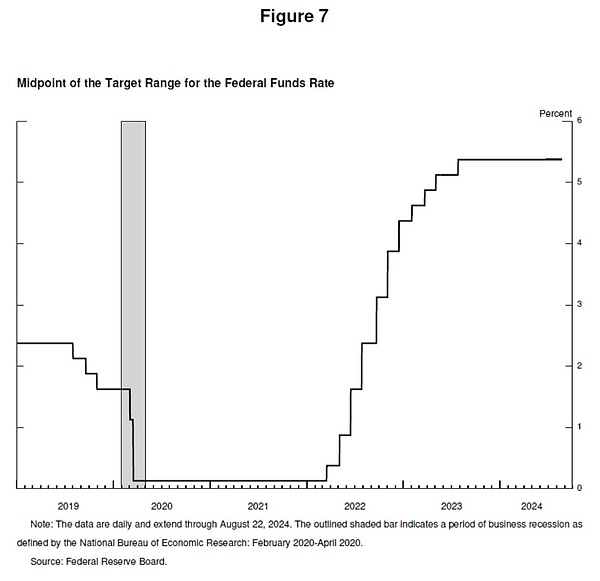

The time has come to adjust policy. The way forward is clear, and the timing and pace of rate cuts will depend on incoming data, the changing outlook, and the balance of risks.

We will do everything we can to support a strong labor market while pursuing further progress on price stability. With policy constraints appropriately converged, there are good reasons to think that the economy will return to 2 percent inflation while maintaining a strong labor market. Our current level of policy rates gives us ample room to address any risks we may face, including the risk of further deterioration in the labor market.

The Rise and Fall of Inflation

Now let’s talk about why inflation has risen, and why it has fallen sharply while unemployment has remained low. There is a growing body of research on these questions, and now is an appropriate time to discuss them. Of course, it is too early to make a definitive assessment. This period will be analyzed and debated long after we are gone.

The outbreak of the coronavirus pandemic quickly shut down the global economy. This was a period of uncertainty and significant downside risks. As often happens in times of crisis, Americans adapted and innovated. Governments around the world responded, notably the unanimous passage of the CARES Act by the U.S. Congress. At the Federal Reserve, we have used our powers to an unprecedented degree to stabilize the financial system and help avoid a depression.

After an impressive but brief recession, the economy began to grow again in mid-2020. As the risk of a long and severe recession recedes and the economy reopens, we face the risk of a repeat of the painful and slow recovery that followed the global financial crisis.

Congress provided substantial additional fiscal support in late 2020 and early 2021. Spending recovered strongly in the first half of 2021. The ongoing pandemic has affected the pattern of the recovery. Persistent concerns about the coronavirus pandemic weighed on spending on in-person services. But pent-up demand, stimulus policies, changes in work and leisure habits caused by the pandemic, and additional savings related to limited spending on services have contributed to a historic surge in consumer spending on goods.

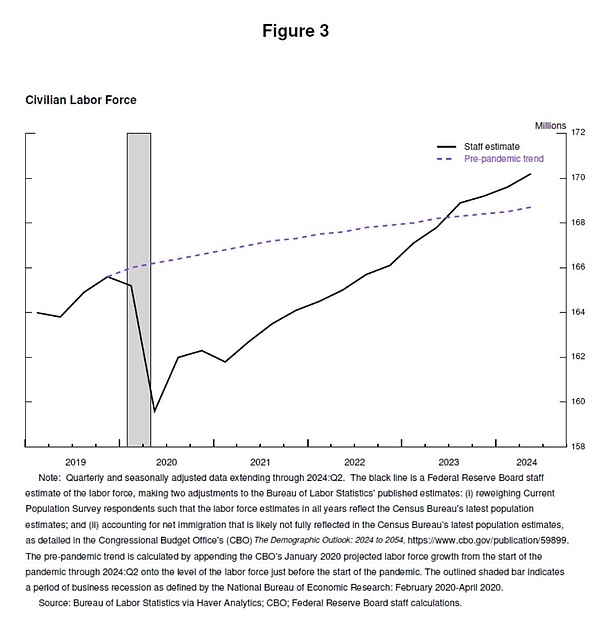

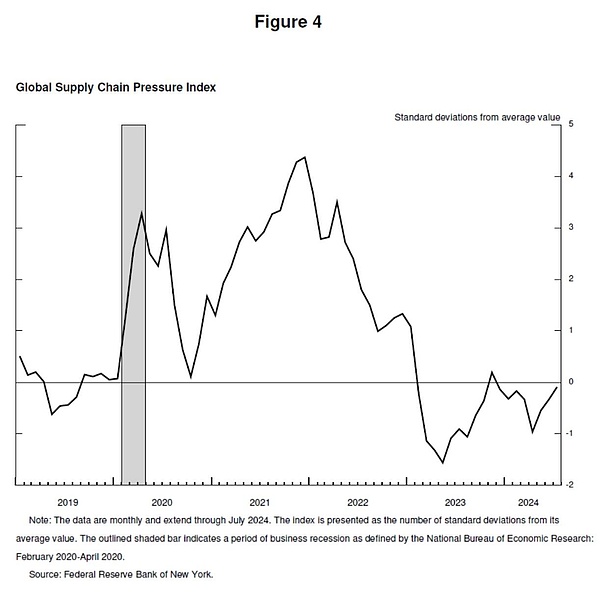

The pandemic has also wreaked havoc on the supply side. Eight million people dropped out of the labor force at the start of the pandemic, and the labor force remains four million below its pre-pandemic level in early 2021. The size of the labor force does not return to its pre-pandemic trend until mid-2023 (Figure 3). Supply chains are being hobbled by worker losses, disruptions to international trade links, and structural changes in the level and composition of demand (Figure 4). Clearly, this is nothing like the slow recovery that followed the global financial crisis.

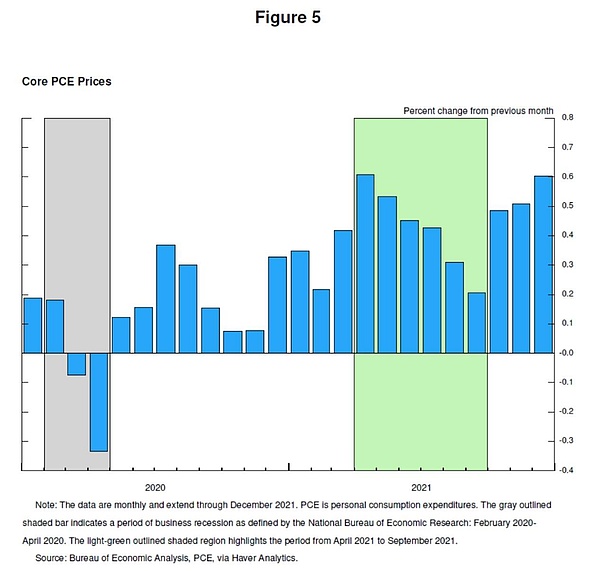

Inflation is starting to show. After running below target throughout 2020, inflation surged in March and April 2021. The initial burst of inflation was concentrated rather than broad-based, with sharp price increases for scarce goods such as automobiles. My colleagues and I initially judged that these pandemic-related inflationary factors would not persist, and therefore the sudden rise in inflation was likely to pass quickly without the need for a monetary policy response. In short, inflation will be temporary. The long-held “correct answer” has been that central banks can ignore temporary increases in inflation as long as inflation expectations remain anchored.

The “temporary” boat is crowded, with most mainstream analysts and advanced economy central bankers supporting this view. They generally expect supply conditions to improve quickly, and a rapid recovery in demand will take its course, with demand shifting from goods to services, lowering inflation.

For a while, the data were consistent with the temporary assumption. Monthly data on core inflation have been falling every month from April to September 2021, albeit at a slower pace than expected (Chart 5). This began to weaken around mid-year, as reflected in our letter. But starting in October, the data turned against the temporary assumption, with inflation rising and extending from goods to services. It is clear that high inflation is not temporary and that a strong policy response is needed if inflation expectations are to remain well anchored. We recognized this and began to shift policy in November, and financial conditions began to tighten. After gradually unwinding the asset purchase program, we began raising interest rates in March 2022.

By early 2022, headline inflation exceeded 6% and core inflation exceeded 5%. A new supply shock emerged: the conflict between Russia and Ukraine led to a sharp rise in energy and commodity prices. The improvement in supply conditions and the shift in demand from goods to services took much longer than expected, partly due to the impact of a new round of COVID-19 in the United States.

High inflation rates are a global phenomenon that reflects a shared history: rapidly increasing demand for goods, tight supply chains, tight labor markets, and sharply higher commodity prices. The nature of this round of global inflation is different from any period since the 1970s. Back then, high inflation was already entrenched, and it was an outcome we did everything we could to avoid.

In mid-2022, the labor market was extremely tight, with more than 6.5 million more people employed than in mid-2021. As health concerns began to ease, workers rejoined the labor force, partially meeting the growth in labor demand. But labor supply remained constrained, and the labor force participation rate in the summer of 2022 remained well below pre-pandemic levels. From March 2022 to the end of the year, the number of job openings was almost twice the number of unemployed people, indicating a severe labor shortage (Figure 6). Inflation also peaked in June 2022 at 7.1%.

Two years ago, I discussed from this podium that addressing inflation would likely bring some pain, including higher unemployment and slower economic growth. Some argued that controlling inflation would require a recession and prolonged high unemployment. I expressed our unconditional commitment to restore price stability across the board and to stay the course until the job is done.

The FOMC has not backed down from fulfilling its responsibilities, and our actions have powerfully demonstrated our resolve to restore price stability. We raised our policy rate by 425 basis points in 2022 and another 100 basis points in 2023. We have kept our policy rate at its current restrictive level since July 2023 (Figure 7).

Inflation peaked in the summer of 2022. Against the backdrop of low unemployment, inflation has fallen 4.5% from its peak two years ago, a welcome and historically rare result.

How was inflation reduced without unemployment rising sharply above the estimated natural rate of unemployment?

Pandemic-related supply and demand distortions and severe shocks to energy and commodity markets were important drivers of high inflation, and reversing them was a key part of the disinflation. The unwinding of these factors took much longer than expected, but ultimately played an important role in the subsequent disinflation. Restrictive monetary policy slowed aggregate demand, which combined with improvements in aggregate supply to reduce inflationary pressures while continuing to maintain a healthy growth rate. As labor demand has also slowed, job vacancy/unemployment rates have normalized from historically high levels, mainly through a decline in job openings rather than large and disruptive layoffs, making the labor market no longer a source of inflationary pressure.

On the importance of inflation expectations. Standard economic models have long reflected the view that as long as inflation expectations are anchored at our target, inflation will return to its target when product and labor markets are in balance without slowing economic growth. That’s what the models say, but the stability of long-term inflation expectations has not been tested by persistently high inflation since the 2000s. Persistent stable inflation is far from guaranteed. Concerns about runaway inflation have fueled the view that disinflation will require a slowdown in the economy (especially the labor market). An important conclusion from recent experience is that stable inflation expectations, combined with forceful central bank action, can promote disinflation without necessarily slowing the economy.

This narrative attributes much of the rise in inflation to the “collision” between an overheated economy and temporarily distorted demand and constrained supply. While researchers differ in their approaches and, to some extent, their conclusions, there seems to be a consensus emerging that, in my opinion, much of the blame for the rise in inflation lies with this collision. In sum, our recovery from the distortions caused by the pandemic, and our efforts to moderate aggregate demand, combined with anchoring expectations, have put inflation on a sustainable path that is increasingly close to our 2% target.

Achieving disinflation while maintaining a strong labor market is only possible if inflation expectations are anchored, reflecting public confidence that the Bank will reach its inflation target of around 2 percent over time. This confidence has been built over decades and reinforced by our actions.

This is my personal assessment, and yours may differ.

Conclusion

I want to emphasize that the pandemic economy has proven to be unlike any other, and we still have much to learn from this extraordinary period. Our Statement on Longer-Run Goals and Monetary Policy Strategy emphasizes our commitment to reviewing our principles and making appropriate adjustments through a comprehensive public review every five years. When we begin this process later this year, we will be open to criticism and new ideas while maintaining the strength of our framework. The limits of our knowledge, made all the more apparent during the pandemic, require us to remain humble and skeptical, focused on learning from the past and applying it flexibly to our current challenges.

JinseFinance

JinseFinance

JinseFinance

JinseFinance JinseFinance

JinseFinance JinseFinance

JinseFinance JinseFinance

JinseFinance JinseFinance

JinseFinance JinseFinance

JinseFinance Weiliang

Weiliang JinseFinance

JinseFinance JinseFinance

JinseFinance JinseFinance

JinseFinance