Author: Research Report; Source: Research Report Intensive Reading

The rapid growth of the U.S. national debt has attracted widespread attention. According to the latest forecast of Bank of America, if the U.S. national debt continues to grow at the rate of the past 100 days (an increase of $907 billion), the total U.S. national debt will exceed the $40 trillion mark on February 6, 2026. This figure is shocking - it took more than 200 years for the United States to accumulate the first $10 trillion national debt since its founding, and now it may add $10 trillion in just 400 days. At the same time, U.S. government spending increased by 11% year-on-year to $7 trillion, and this fiscal expansion trend does not see any signs of significant improvement in the short term.

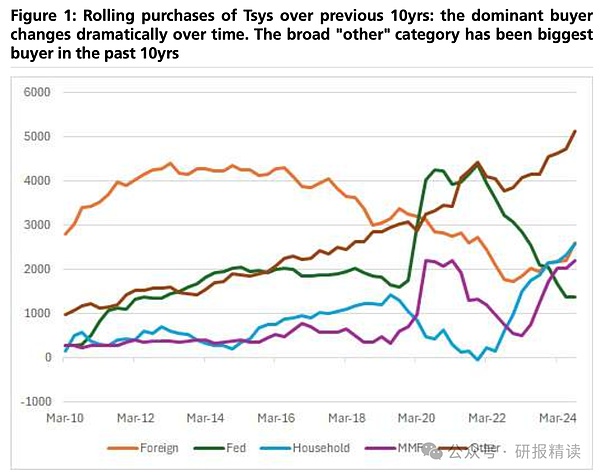

Faced with such a huge supply, the market is naturally concerned about: Who will pay for these treasury bonds? Especially in the context of the Federal Reserve's continued quantitative tightening (QT), there is great uncertainty about the purchasing power and willingness of institutional investors, which are traditionally considered to be the main buyers.

PART ONE Buyer 1: Pension funds and insurance companies

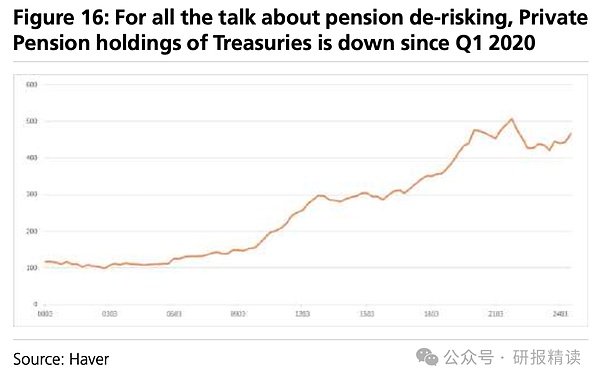

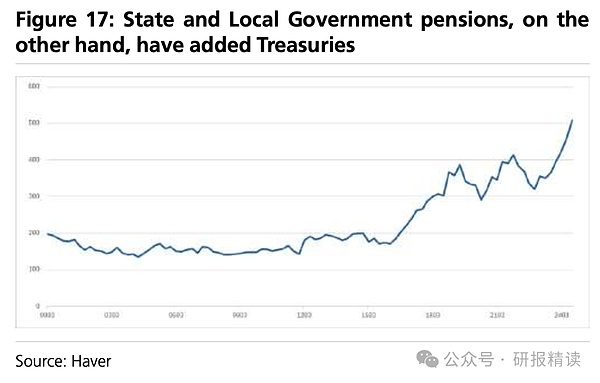

Let's first look at the two major institutional investors, pension funds and insurance companies. Although they manage trillions of assets, they are actually not keen on buying US bonds directly. For example, private pension funds hold only 3% of their total assets in U.S. Treasuries, while state and local government pension funds hold only about 5%. These institutions prefer to gain exposure to interest rate risk through derivatives and invest cash in assets such as credit bonds and structured products with higher yields. Life insurance companies' U.S. Treasury holdings have remained stable over the past 25 years, with no significant growth. Even property insurance companies, which have seen an increase in liquidity needs recently due to factors such as extreme weather, have only doubled their U.S. Treasury holdings as a percentage of total assets from a low level.

PART TWO Buyer 2: Banks

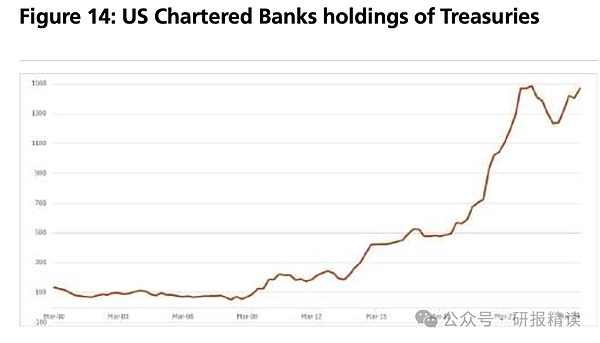

The situation of banks is also very interesting. On the surface, the proportion of U.S. Treasuries held by banks in their total assets has increased from less than 2% before the 2008 financial crisis to 6% now, but this is mainly due to regulatory requirements.

In fact,banks do not bear too much interest rate risk, and the long-term U.S. Treasuries they purchase often hedge the interest rate risk through asset swaps and other means. Regulators also do not want banks to take on too much interest rate risk. Even if regulation is relaxed in the future, such as excluding US Treasuries from the calculation of the supplementary leverage ratio (SLR), this will mainly improve the liquidity of the US Treasury repo market without significantly increasing banks' actual demand for US Treasuries.

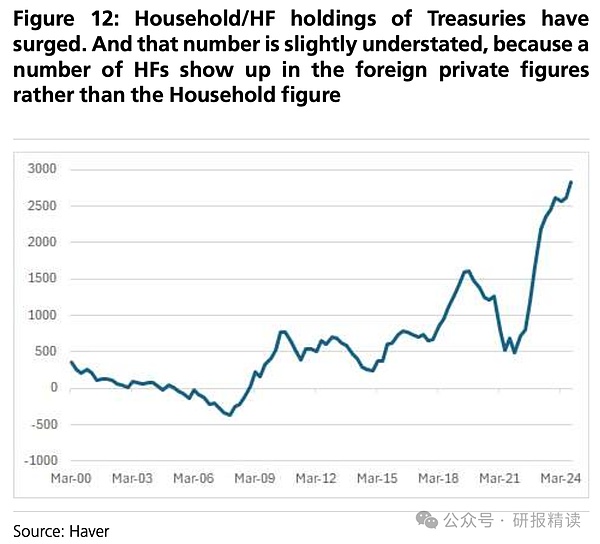

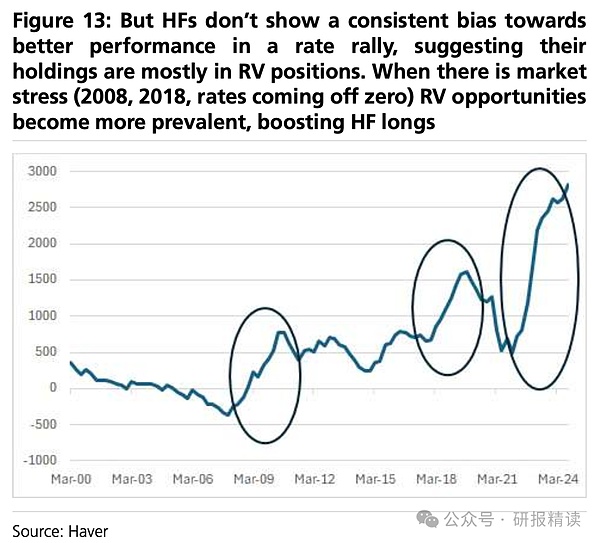

PART THREE Buyer Three: Hedge Funds

Hedge funds have indeed increased their holdings of US Treasuries recently, which has played an important role in providing market liquidity. However, it should be noted that their holdings are often based on various arbitrage transactions and do not represent long-term demand for US Treasuries. Judging from the statements of regulatory agencies such as the Bank for International Settlements (BIS), the Bank of England and the Bank of Canada, they are concerned about the growing intermediary role of hedge funds in the U.S. Treasury market. Once market volatility increases or regulation is tightened, hedge funds are likely to be forced to reduce their holdings of U.S. Treasury bonds.

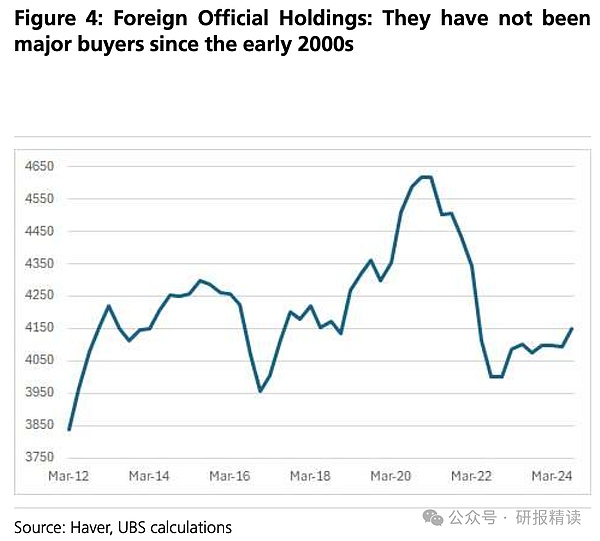

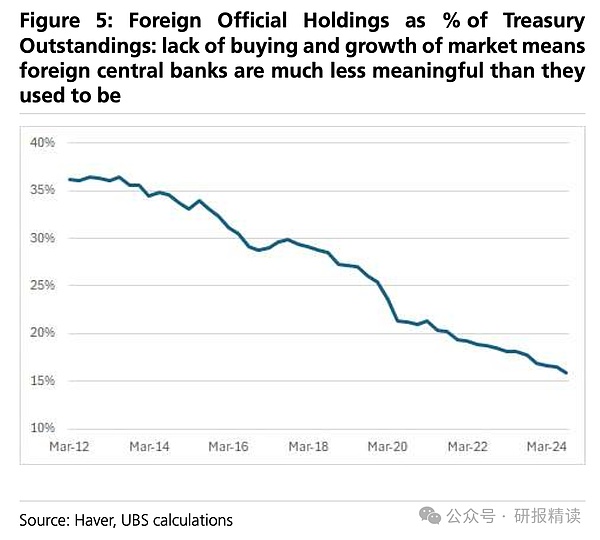

PART FOUR Buyer Four: Foreign Central Banks

Foreign central banks were once one of the most important buyers of U.S. debt. In the early 2000s, countries such as Japan and China accumulated a large amount of US dollar assets and invested in US Treasuries in order to maintain exchange rate stability. But now the situation has changed fundamentally - in an environment of a strong US dollar, many central banks have to sell US Treasuries to obtain US dollars to maintain their exchange rates. Some central banks have even reserved a large amount of US dollars in the Federal Reserve's foreign exchange reverse repurchase facility (RRP) in advance to cope with possible exchange rate pressures. Unless the US dollar weakens significantly, foreign official demand for US Treasuries is expected to remain weak.

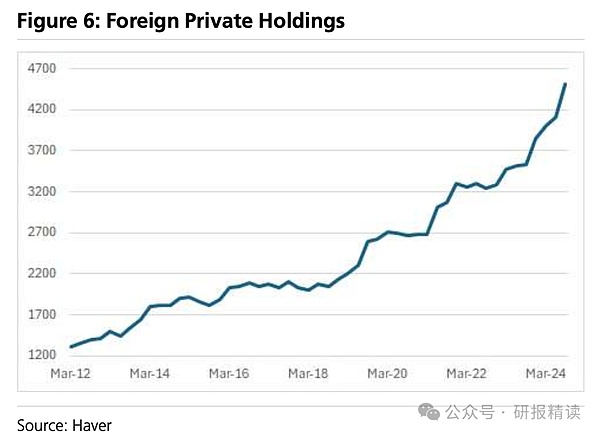

PART FIVE Buyer Five: Overseas Private Investors

As for whetherprivate overseas investors are willing to buy U.S. Treasuries, it mainly depends on two factors: the relative attractiveness of yields and exchange rate risks.

Let's use a simple example to illustrate. Suppose a Japanese investor is considering whether to buy Japanese government bonds or U.S. Treasuries. If the yield on Japanese government bonds is 1% and the yield on US government bonds is 4%, it seems that buying US government bonds is more cost-effective. But the problem is not that simple, because the investor faces exchange rate risk - if the US dollar depreciates by 10% against the yen during the holding period, then the 4% yield may become a negative 6% actual loss.

In order to avoid this exchange rate risk, investors can hedge the exchange rate through financial derivatives. But hedging has costs, and this cost mainly depends on the shape of the interest rate curves of the two countries. Simply put, if the long-term interest rate in the United States is much higher than the short-term interest rate (that is, the yield curve is steep), the hedging cost is relatively low; conversely, if the long-term and short-term interest rates in the United States are similar (that is, the yield curve is flat), the hedging cost will be higher.

In recent years, the US Treasury yield curve has been relatively flat compared to other developed markets. This means that if overseas investors completely hedge their exchange rate risks, it may be better to buy bonds in their own country. To give a specific example, suppose a European investor buys a 10-year US Treasury bond and the actual yield after hedging the exchange rate risk is only 2%, while the yield of German government bonds in the same period is 2.5%. Obviously, buying US Treasury bonds is unattractive. Of course, if investors are optimistic about the trend of the US dollar, they may choose not to hedge the exchange rate risk or only hedge part of it. Indeed, in the context of the continued strength of the US dollar in the past few years, many overseas investors have done so. But this strategy also has risks - if the US dollar starts to weaken, these investors may have to start hedging the exchange rate risk, and once they start hedging, the yield advantage of holding US Treasury bonds may disappear. In this case, they are likely to choose to reduce their holdings of US Treasury bonds and invest in other assets instead.

In short, for overseas private investors, buying U.S. Treasuries not only requires considering the surface yield, but also weighing the exchange rate risk and hedging costs. In the current market environment, these factors combined may inhibit their enthusiasm for buying U.S. Treasuries. This is why the market is worried that overseas private investors may not be able to become stable buyers in the case of a significant increase in supply.

In general, while the supply has increased significantly, the purchasing power and willingness of traditional buyers are facing challenges.

This imbalance between supply and demand means that the U.S. Treasury market may need higher yields to attract sufficient demand. Of course, If economic growth slows, then safe-haven demand may drive various investors to increase their holdings of U.S. Treasuries. Regulatory reforms may also theoretically create some new demand, but UBS's analysis believes that this effect may be limited. Under the current macroeconomic environment, the realization of the balance between supply and demand of US Treasury bonds is still full of uncertainty. What is more worrying to the market is that such a huge debt scale also brings potential default risks. Although as the world's largest economy and the issuer of the US dollar, the possibility of sovereign debt default in the United States is extremely low, even a short-term technical default may trigger serious financial market turmoil. This is because US Treasury bonds play a unique and critical role in the global financial system. It is not only the world's most important "safe asset", but also the benchmark for financial market pricing, and plays a core role in collateral guarantees, derivative transactions, etc. Taking the repo market as an example, US Treasury bonds are the main collateral, supporting trillions of dollars in short-term financing every day. If the U.S. debt defaults, this market may be paralyzed immediately. In addition, U.S. debt is also the most important liquidity reserve for global financial institutions. Banks, insurance companies, pension funds and other institutions all hold a large amount of U.S. debt as a liquidity buffer. Once the U.S. debt price fluctuates sharply or liquidity dries up, these institutions may be forced to sell assets, triggering a chain reaction. Especially in the current situation where the global debt level is generally high, the sharp fluctuations in the U.S. debt market may be transmitted to other markets through various channels, triggering a wider financial crisis.

Historically, in 1979, the United States had a short-term small-scale debt default due to technical reasons. The impact at that time was quite significant - causing short-term Treasury yields to soar by 60 basis points, and the financing costs of the Treasury market continued to be under pressure in the following months. The current U.S. Treasury market is much larger and more interconnected than it was then. If a similar situation occurs, the impact will be even more far-reaching.

Therefore, ensuring the smooth operation of the U.S. Treasury market is not only related to the fiscal situation of the United States itself, but also to global financial stability. This is also an important reason why all parties are so concerned about the imbalance between the supply and demand of U.S. Treasury bonds. In this context, the U.S. government, the Federal Reserve and major market participants need to act prudently, both to control the growth rate of debt and to maintain market confidence and avoid sharp fluctuations. At the same time, other countries also need to prepare for a rainy day, appropriately diversify reserve assets, and enhance the resilience of the financial system.

This game of supply and demand surrounding U.S. debt not only concerns the sustainability of U.S. finances, but also the stability of the global financial system. As the scale of U.S. debt continues to expand, the market's attention to this issue will only increase further.

JinseFinance

JinseFinance

JinseFinance

JinseFinance JinseFinance

JinseFinance JinseFinance

JinseFinance JinseFinance

JinseFinance Hui Xin

Hui Xin JinseFinance

JinseFinance JinseFinance

JinseFinance Future

Future Cointelegraph

Cointelegraph Cointelegraph

Cointelegraph