This article has to mix Chinese and English to circumvent certain issues, which is a helpless form of linguistic corruption. Anyone who's been in the tech world for a long time can't escape Moore's Law. It's a familiar saying: The number of transistors on a chip doubles every eighteen to twenty-four months, and computing power rises accordingly. Don't dismiss it as just an empirical formula; it has shaped the world over the past fifty years. Computers are getting faster, phones are getting smarter, and AI can even write articles, all thanks to Moore's Law. I sometimes wonder if society follows a similar pattern. It's not about transistors, but about us humans. How we organize, how we make decisions, and how we handle complex problems—is there a kind of "computing power" that's escalating? The more I think about it, the more I believe there is—and that thing is democracy. Democracy isn't just empty talk; it's a mechanism, a machine. It aggregates the information and judgments of millions of people and produces a single result. It's slow, noisy, and chaotic, but it's society's "supercomputer." Democracy is essentially a distributed computer. Think of it this way: when one person votes, speaks, or expresses an opinion, it's like a CPU executing a single instruction. A single instruction might seem insignificant, but when millions or tens of millions of these instructions are combined, society as a whole completes a massive computation. Autocracy is more like a single machine. All decision-making is centralized on a single CPU, resulting in swift responses. Building a highway or undertaking a major engineering project can be accomplished with a few nods. It may appear efficient, but if the CPU crashes, the entire state goes blue screen. We've seen countless examples of this throughout history. Democracy is a distributed system. It has many nodes, high latency, and often incessant contention, but it's not prone to crashes. If one part breaks down, others can pick up the slack. The more complex a society becomes, the more it needs this kind of distributed architecture. Let's take a fresh example: PolyMarket. It's a prediction market platform where users can buy "yes" or "no" shares to bet on whether a certain event will occur in the future, such as "Will the US fall into a recession in 2025?" The price of the share represents everyone's perceived probability of the event. New information immediately moves the price, and the market is constantly correcting. It's like a small distributed computer: different people place bets with different information, and the final market price is a composite result. It's not perfect, but it's often more reliable than expert predictions.

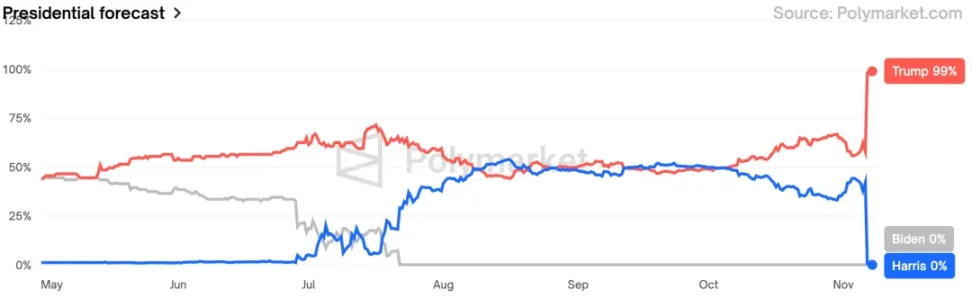

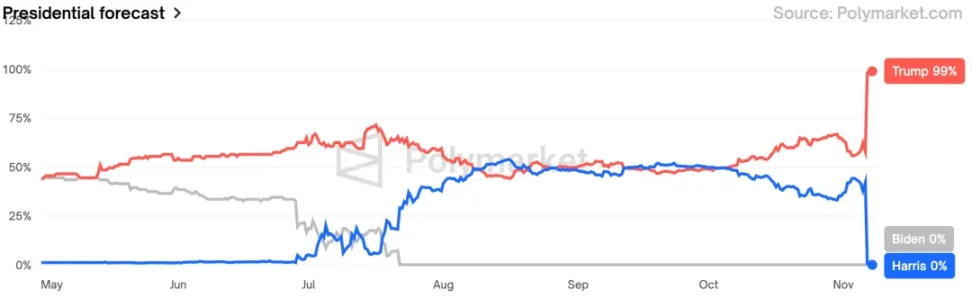

The winning odds trends of Trump, Biden, and Harris on Polymarket during the 2024 US election accurately predicted the outcome.

This is the "computing power of democracy": it doesn't rely on a few geniuses' intuition, but on the continuous input and correction of countless ordinary people, synthesizing a judgment that is closer to reality.

Of course, this machine has its flaws.

Some people may say: Why is the democratic society we often see such a mess? Congress is squabbling, the government is shut down, and the election is a dog-eat-dog affair. How can this be called a "supercomputer"? It's like the first time you look at the logs of a distributed computer: a screen full of errors, delays, and conflicts. To the untrained eye, it looks chaotic, but an expert knows this is the norm. The benefit of a distributed system isn't that it has no problems, but that it can keep running even when problems arise. However, this "democracy computer" does have its own bottlenecks: Information noise: Everyone has a voice, and false information and spam are everywhere, reducing the signal-to-noise ratio. Polarization: Nodes don't communicate, but instead curse each other, wasting computing power on internal friction. Short-termism: Driven by elections, everyone pursues immediate gains, leaving no one willing to pay for long-term problems. Asymmetry: Some people have access to more data, while others only consume gossip, resulting in a significant disparity in input quality. Therefore, the problem isn't that "democracy is useless," but rather that "how to effectively utilize computing power." To improve quality, we need to improve algorithms—for example, faster fact-checking, smoother communication channels, and more balanced incentive structures. With the arrival of AI, we need to carefully consider how this machine will function. The crucial question now arises: Will AI accelerate the computing power of democracy, or replace it? If AI is used to help filter information, predict policy consequences, and provide multi-faceted analysis, then it is an accelerator of democracy. The democratic machine, once noisy, now has a smart assistant that can help cut through the noise. However, if AI is controlled by a small number of people, it becomes dangerous. It could become a super-single machine, draining computing power and creating a new kind of autocracy that appears efficient but lacks the ability to correct errors. Therefore, the key to the future lies not in whether AI can surpass democracy, but in whether we can make AI a part of democracy. Open source, transparent, and decentralized, this allows diverse groups to use it, rather than being monopolized by a few institutions. Ultimately, democracy's computing power isn't perfect—it's slow, chaotic, and often disappointing. But it possesses a unique quality that no one can replace: fault tolerance. It allows for mistakes, allows for corrections, and allows for the coexistence of diverse systems. In a complex world, fault tolerance is more important than speed. Whoever can effectively combine the judgments of more people will go further. Moore's Law may have its limits, but the computing power of democracy will always have room to grow as long as human society continues to grow in complexity. (Image: Loop) This is an animated short film directed by Argentinian director Pablo Polledri. It uses abstract and repetitive visual language to depict a mechanized, institutionalized society: people operate like gears, repeating the same actions day after day until "love" breaks free... (Image: Loop)

Catherine

Catherine