Author: Michael Nadeau, Source: The DeFi Report, Translation: BitpushNews

Last week, the Federal Reserve lowered interest rates to a target range of 3.50%–3.75%—a move that was fully priced in by the market and largely expected.

What truly surprised the market was the Fed's announcement that it would purchase $40 billion in short-term Treasury bills (T-bills) per month, which was quickly labeled by some as a "lightweight version of quantitative easing (QE-lite)".

In today's report, we will delve into what this policy has changed and what it hasn't. Furthermore, we will explain why this distinction is crucial for risk assets.

1. "Short-Term" Positioning

The Fed cut rates as expected.

This is the third rate cut this year and the sixth since September 2024. The total rate has been lowered by 175 basis points, pushing the federal funds rate to its lowest level in about three years. In addition to the rate cut, Powell also announced that the Federal Reserve will begin "Reserve Management Purchases" of short-term Treasury securities starting in December, at a rate of $40 billion per month. Given the continued tightness in the repo market and liquidity in the banking sector, this move was entirely expected. The current consensus in the market (whether on the X platform or on CNBC) is that this is a "dovish" policy shift. Discussions about whether the Federal Reserve's announcement was equivalent to "money printing," "QE," or "QE-lite" immediately dominated social media timelines. Our observations: As market observers, we observe that market sentiment remains risk-on. In this state, we expect investors to overfit policy headlines, attempting to construct bullish logic while ignoring the specific mechanisms by which policies translate into actual financial conditions. Our view is that the Fed's new policies are beneficial to the financial market pipeline, but not necessarily to risk assets. Where does our understanding differ from the prevailing market consensus? Our views are as follows: Short-term Treasury purchases ≠ Absorbing market duration. The Fed is buying short-term Treasury bills (T-bills), not long-term interest-bearing bonds (coupons). This does not remove the market's interest rate sensitivity (duration). While short-term purchases may slightly reduce future long-term bond issuance, this does not help compress the term premium. Currently, about 84% of Treasury issuance is in short-term notes, so this policy does not substantially change the duration structure faced by investors. Financial conditions are not broadly accommodative. These reserve management purchases, designed to stabilize the repo market and bank liquidity, do not systematically lower real interest rates, corporate borrowing costs, mortgage rates, or equity discount rates. Its impact is localized and functional, not widespread monetary easing. Therefore, no, this is not QE. This is not financial repression. To be clear, the abbreviation doesn't matter; you can call it money printing if you want, but it doesn't intentionally suppress long-term yields by removing duration—which is precisely what forces investors to the high end of the risk curve. This hasn't happened yet. The price action of BTC and the Nasdaq since last Wednesday confirms this. What will change our view? We believe BTC (and risk assets more broadly) will have its moment of glory. But that will happen after QE (or whatever the Fed calls the next phase of financial repression). The moment arrives when the following occur: The Federal Reserve artificially suppresses the long end of the yield curve (or signals this to the market). Real interest rates fall (due to rising inflation expectations). Corporate borrowing costs fall (fueling tech stocks/Nasdaq). Term premiums compress (long-term interest rates fall). Equity discount rates fall (forcing investors into longer-term risk assets). Mortgage rates fall (driven by suppression of long-term interest rates).

At that time, investors will smell the “financial repression” and adjust their portfolios. We are not currently in this environment, but we believe it is coming soon. Although timing is always difficult to grasp, our baseline assumption is that volatility will increase significantly in the first quarter of next year.

This is the short-term scenario we envision.

2. The Bigger Picture

The deeper issue is not the Fed’s short-term policies, but the global trade war (currency war) and the tensions it creates at the core of the dollar system.

Why?

The US is moving towards the next strategic phase: bringing manufacturing back, reshaping the global trade balance, and competing in strategically essential industries such as AI. This goal directly conflicts with the dollar’s role as the world’s reserve currency.

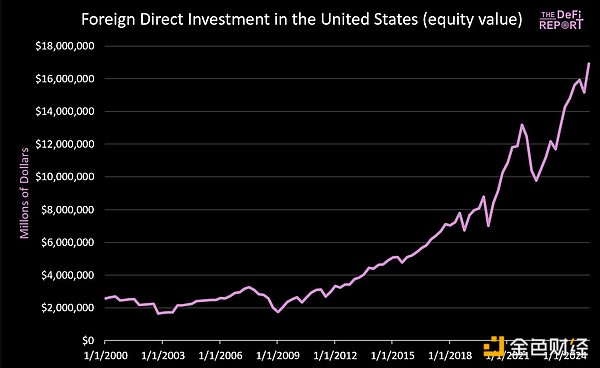

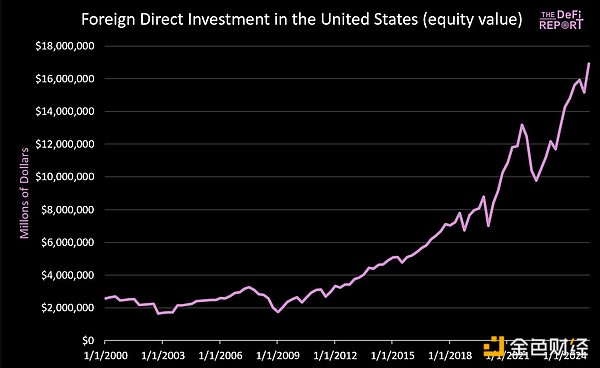

Reserve currency status can only be maintained if the United States maintains a persistent trade deficit. Under the current system, dollars are sent overseas to purchase goods, and then flow back to the US capital markets through a cycle of Treasury bonds and risky assets. This is the essence of the "Triffin's Dilemma." Since January 1, 2000: More than $14 trillion has flowed into the US capital markets (this does not include the $9 trillion in bonds currently held by foreigners).

At the same time, approximately $16 trillion flowed overseas to pay for goods. Efforts to reduce the trade deficit will inevitably reduce the flow of circulating capital back to the US market. While Trump touted the commitment of Japan and other countries to "invest $550 billion in US industry," he failed to address the fact that Japanese (and other countries') capital cannot simultaneously exist in both manufacturing and capital markets. We believe this tension will not be resolved smoothly. Instead, we anticipate higher volatility, asset repricing, and eventual currency adjustment (i.e., a depreciation of the dollar and a reduction in the real value of US Treasury bonds). Our core argument is that China is artificially devaluing the yuan (to give its exports an artificial price advantage), while the dollar is artificially overvalued due to foreign capital investment (leading to relatively low prices for imports). We believe that a forced dollar depreciation may be imminent to address this structural imbalance. In our view, this is the only viable path to resolving the global trade imbalance. Under the new round of financial repression, the market will ultimately determine which assets or markets qualify as "stores of value." The key question is whether US Treasury bonds can continue to serve as global reserve assets when everything settles down. We believe that Bitcoin and other global, non-sovereign stores of value (such as gold) will play a far more important role than they do now. This is because they are scarce and do not rely on any policy credit. This is the "macroeconomic landscape" we are seeing.

Catherine

Catherine