Author of the article:thiccy Article compiler:Block unicorn

This article exploresthe shift in risk appetite from frenzy to the worship of big prizes, and its broader social impact

. The article involves some simple math, but it's worth reading.

Imagine that you are playing a coin tossing game. How many times will you toss?

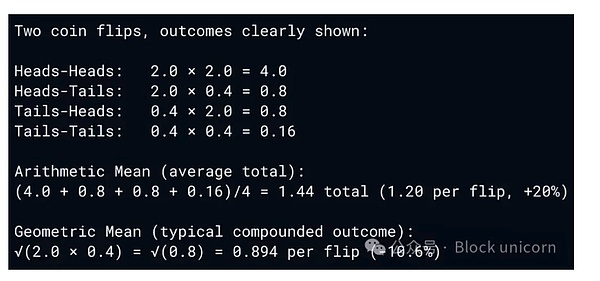

At first glance, this game looks like a money printing machine. The expected return on each coin toss is 20% of your net worth, so in theory you should be able to toss the coin infinitely and eventually accumulate all the wealth in the world.

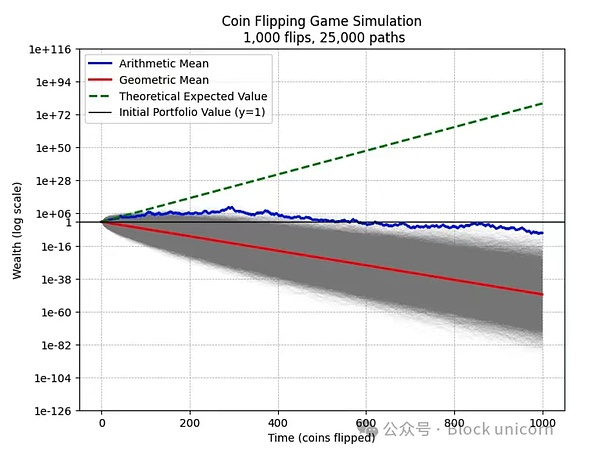

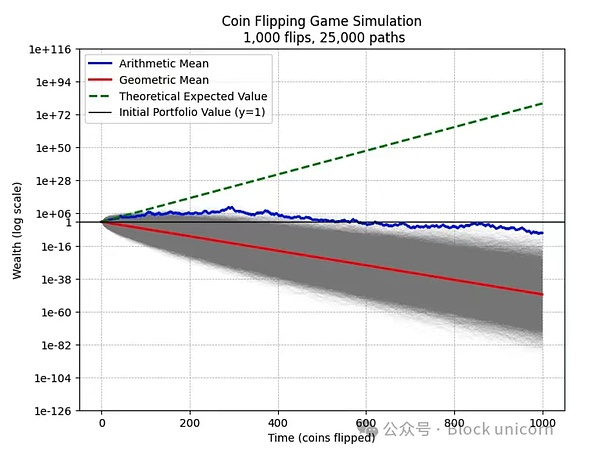

However, if we simulate 25,000 people each tossing a coin 1,000 times, almost everyone's result is close to $0.

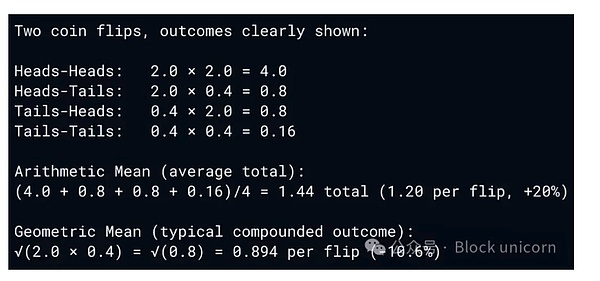

The reason almost all results tend toward 0 is due to the multiplicative nature of repeated coin tossing. Although the expected value of the game (i.e. the arithmetic mean) is a 20% increase in return for each coin toss, the geometric mean is negative, which means that in the long run, coin tosses actually compound negatively.

What's going on? Here's an intuitive explanation:

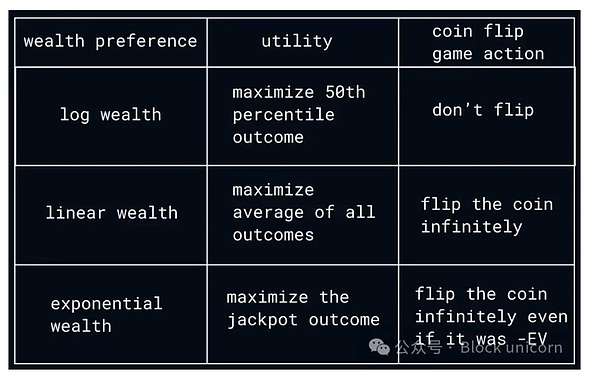

The arithmetic mean measures the average wealth created over all possible outcomes. In our coin tossing game, wealth is highly skewed toward the rare jackpot scenario. The geometric mean measures the wealth you can expect from the middle outcomes.

The simulation above shows the difference. Almost all paths asymptotically return to zero. In this game, you need to toss 570 heads and 430 tails to break even. After 1,000 coin tosses, all the expected value is concentrated in the jackpot outcome of just 0.0001%, the rare occasions when a large number of heads are tossed.

The difference between the arithmetic mean and the geometric mean constitutes what I call the "jackpot paradox". Physicists call it the "ergodicity problem", traders call it "volatility drag". When expected value is hidden in the rare jackpot, you can't always rely on it. The risk of excessive pursuit of jackpots turns positive expected value straight to zero. In a world of compound returns, the dose makes the difference.

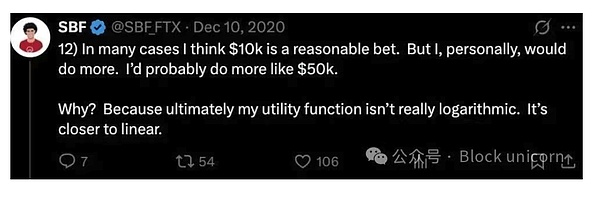

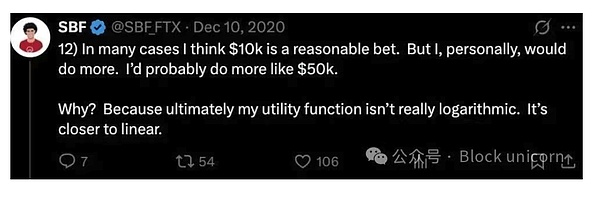

The cryptocurrency culture of the early 2000s is a vivid example of the jackpot paradox. SBF (Sam Bankman-Freed) once opened the discussion of wealth preferences in a tweet.

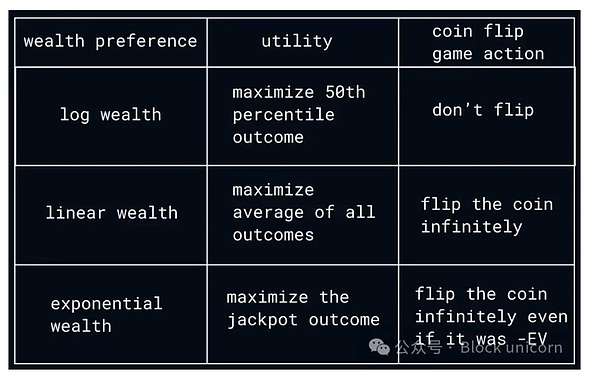

SBF proudly proclaims that he has a linear wealth preference. He argues that since his goal is to give away all his wealth, doubling from $10 billion to $20 billion is just as important as going from $0 to $10 billion, so making a huge, high-risk bet is logically worthwhile from a civilizational perspective.

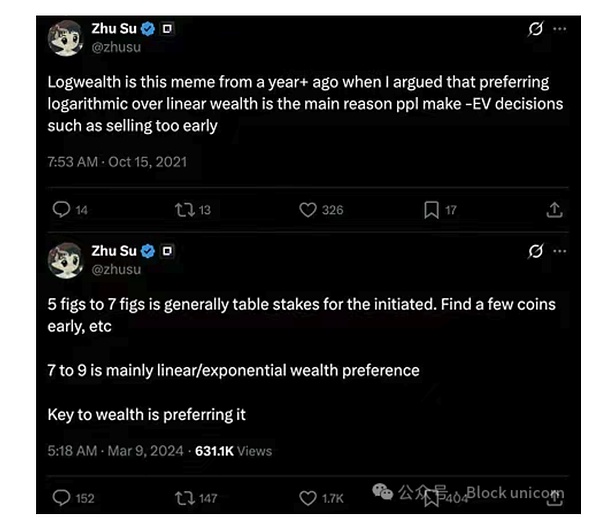

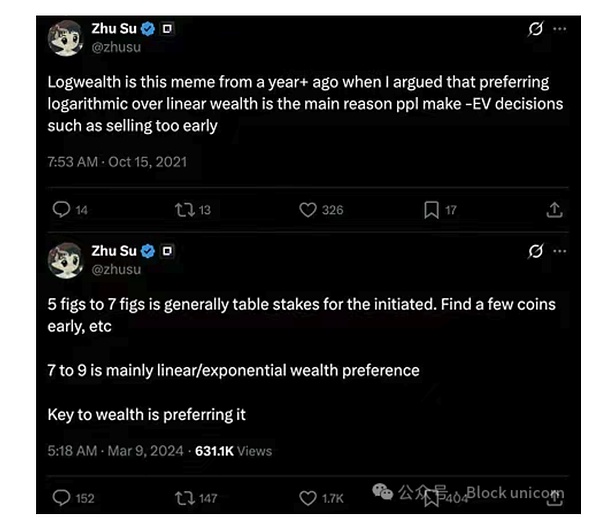

Su Zhu of Three Arrows Capital echoed this linear wealth preference and further proposed an exponential wealth preference.

Exponential wealth preference: Each dollar of new wealth is more valuable than the previous dollar, so as wealth grows, you increase your risk appetite and are willing to pay a premium for the jackpot.

Here are the three wealth preferences corresponding to the coin tossing game mentioned above.

Given our understanding of the jackpot paradox, it is obvious that SBF and Three Arrows were, in a sense, flipping a coin infinitely. This mentality was how they built their fortunes in the first place. Likewise, it is unsurprising and obvious in hindsight that SBF and Three Arrows both lost $10 billion in wealth. Perhaps in some distant parallel universe, they were billionaires, which might justify the risks they took.

These plunges are not just a cautionary tale about the mathematics of risk management, but a reflection of a deeper macro-cultural shift toward a preference for linear or even exponential wealth.

Founders are expected to adopt a linear wealth mindset, take huge risks, and maximize expected value because they are cogs in the venture capital machine that relies on power-law distributions for success. Stories of Elon Musk, Jeff Bezos, and Mark Zuckerberg betting everything on their own and ending up with the world’s largest individual wealth reinforce the myths that drive the entire venture capital industry, while survivorship bias cleverly ignores the millions of founders who have lost everything. Only the elite few who can cross the increasingly steep power-law threshold can be saved.

This pursuit of ultra-high risk has permeated everyday culture. Wage growth has severely lagged behind the compounding of capital, leading ordinary people to increasingly view jackpots with negative expected value as their best chance for true upward mobility. Online gambling, zero-day expiration options, retail meme stocks, sports betting, and crypto meme coins all demonstrate the phenomenon of exponential wealth preferences. Technology makes speculation effortless, while social media propagates every new story of overnight wealth, drawing a wider range of people like moths to a flame into a huge losing gamble.

We are becoming a culture that worships the jackpot, and the value of existence is increasingly reduced to zero.

AI exacerbates this trend, further devaluing labor and exacerbating the winner-take-all situation. Techno-optimists dream of a post-GAAI world of abundance where humans devote their time to art and leisure, but this looks more like billions of people chasing negative capital and status "jackpots" with UBI allowances. Or maybe, perhaps the "up and up" e/acc logo should be redrawn to reflect the countless paths to zero along the way, which is the true contour of the "jackpot era".

In its most extreme form, capitalism behaves like a collectivist hive. The mathematics of the jackpot paradox suggests that it is rational for civilizations to treat humans as interchangeable labor, sacrificing millions of worker bees to maximize the linear expected value of the entire hive. This may be most efficient for aggregate growth, but it severely distributes purpose and meaning.

Marc Andreessen’s techno-optimist manifesto warned that “humans are not meant to be kept in captivity; they are meant to be useful, productive, and proud.”

Yet the rapid pace of technological development and increasingly radical shifts in incentives for risk-taking are pushing us toward exactly the outcome he warned about. In the “jackpot era,” the impetus for economic growth comes at the expense of our fellow citizens. Utility, productivity, and pride are increasingly reserved for a privileged few who win out over the competition. We have raised the average at the expense of the median, leading to a growing gap in mobility, status, and dignity that breeds a culture of negative sums across the economy. The resulting externalities manifest themselves in social unrest, starting with the election of demagogues and ending with violent revolutions, which can exact a huge toll on the compounding growth of civilization.

As someone who makes a living trading the cryptocurrency markets, I’ve witnessed firsthand the depravity and desperation that comes with the cultural shift. Like the jackpot simulation, my wins were built on the failures of a thousand other traders. It’s a monument to wasted human potential.

When industry insiders ask me for trading advice, I almost always find the same pattern. They’re all taking too much risk and losing too much. Behind this is usually a scarcity mentality, a lingering sense of being “left behind,” and an urge to make a quick profit.

My answer is always the same: Instead of increasing risk, accumulate more edge. Don’t destroy yourself chasing the jackpot. Logarithmic wealth is what matters. Maximize 50% outcomes. Create your own luck.

Avoid large drawdowns. You’ll get there eventually.

But most people will never achieve a consistent edge. “Win more times” is not a scalable advice. In the rat race of techno-feudalism, meaning and purpose always go to the winner. Which brings us back to the question of meaning. Perhaps what we need is a new religious revival that reconciles ancient spiritual teachings with the realities of modern technology.

Christianity spread because it promised that anyone could be saved. Buddhism spread because anyone could be enlightened.

A similar system in the modern era must do the same thing, providing dignity, purpose, and a path forward for all people so that they do not destroy themselves in the pursuit of the grand prize.

Kikyo

Kikyo