Source: Dragonfly; Compiled by: Wuzhu, Golden Finance

Airdrops are a strategic tool for blockchain adoption and value distribution

Airdrops distribute tokens directly to wallet addresses (usually for free) and are a strategic tool for blockchain projects to enhance user engagement, decentralize token distribution, and reward community loyalty. This analysis explores the impact of airdrops in the blockchain ecosystem, providing insights into how they contribute to the broader goals of value creation and distribution in the emerging digital economy.

We analyzed data from 12 airdrops (11 geo-blocked airdrops and 1 non-geo-blocked airdrop as a control) conducted between 2019 and 2023 to determine the economic impact of preventing US users from claiming tokens.

Number of Americans impacted by geo-blocking: We estimate that in 2024, 920,000 to 5.2 million active US users (5-10% of the estimated 18.4 million to 52.3 million crypto holders in the US) are generally impacted by geo-blocking policies. These policies restrict participation in airdrops and limit their use of certain projects.

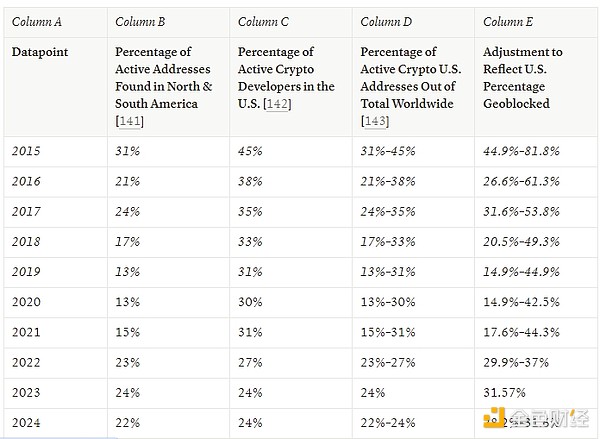

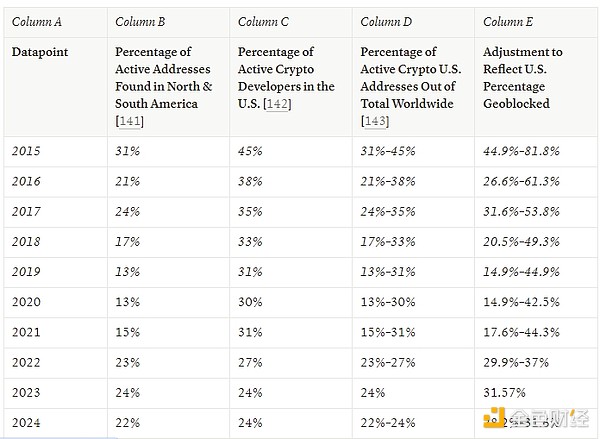

Percentage of US active addresses in 2024: Approximately 22-24% of all active crypto addresses worldwide belong to US residents.

Total value of airdrops in our sample: Across our sample of 11 projects, they have created a total value of approximately $7.16 billion to date, with approximately 1.9 million claimants participating worldwide during this period, and an average median claim value of approximately $46,000 per eligible address.

Estimated revenue losses for US users based on our sample: Across our sample of 11 geo-blocked airdrops, estimated total revenue losses for US users between 2020 and 2024 range from $1.84 billion to $2.64 billion.

Estimated revenue losses for US users based on CoinGecko’s sample: Applying our percentage of active addresses in the US to another sample of 21 geo-blocked airdrops analyzed by CoinGecko, potential total revenue losses for Americans between 2020 and 2024 could range from $3.49 billion to $5.02 billion.

Personal Tax Revenue Lost from Geo-Blocked Airdrops: Based on our sample of geo-blocked projects (for the lower bound) and CoinGecko (for the upper bound), estimates of lost federal tax revenue in 2024 from geo-blocked airdrop revenue range from $418 million to $1.1 billion, with an additional estimated $107 million to $284 million in lost state taxes. Overall, this translates to an estimated tax loss of $525 million to $1.38 billion. These estimates do not include the additional taxes that would be incurred from capital gains taxes upon the eventual sale of these tokens, another lost source of government revenue.

Corporate Tax Losses from Offshoring: The movement of cryptocurrency operations overseas has significantly reduced U.S. tax revenues. For example, Tether reported $6.2 billion in profits in 2024, but the company is incorporated overseas and could have owed about $1.3 billion in federal corporate taxes and $316 million in state taxes if it had fully accepted U.S. taxation. While the actual liability depends on the corporate structure, this is just one company, which suggests that there are broader tax losses for cryptocurrency companies operating overseas.

Foreword

Cryptocurrency and blockchain technology are not fleeting technological trends; they are a major shift in the global economic landscape, providing the United States with a golden opportunity to provide visionary leadership and pioneering governance in this transformative industry. However, rather than accepting this role, the United States has found itself mired in political infighting and efforts to derail the development of this new model.

In such an environment, it is not surprising that many crypto projects are reluctant to engage with U.S. users, as they are hindered by the ambiguous application of U.S. law to digital assets. This uncertainty has led to significant financial losses and limited opportunities for U.S. users to participate in the industry, including participating in airdrops - an innovative method of distributing new tokens and promoting user participation.

This report seeks to provide data-driven insights into the role of cryptocurrency airdrops in accelerating economic growth and illustrate the financial losses incurred as a result of restrictive U.S. policies. It will address the urgent need for a regulatory framework that supports innovation while providing clear guidelines to protect investors and the integrity of the market. Our analysis dives into the tangible economic impacts of current regulatory practices, including detailed metrics on the financial impact of geo-fencing U.S. users against airdrops and the resulting loss of government tax revenue.

By examining these key factors, as well as a broader analysis of the U.S. regulatory environment and its impact on the cryptocurrency space, we advocate for regulatory changes. These adjustments would enable U.S. citizens and businesses to actively and effectively participate in the global cryptocurrency market, leveraging airdrops to stimulate job creation, drive business growth, and increase tax revenues. The continued evolution of the global digital economy and the need for the United States to adopt a more competitive and supportive regulatory stance to maintain its leadership underscore the urgency of this research.

This paper takes a two-pronged approach to analyzing airdrop distribution, leveraging both off-chain and on-chain data sources. By combining these complementary datasets, this analysis aims to provide a comprehensive assessment of distribution patterns, token claims, and valuation dynamics across multiple projects in the United States. Our approach is designed to test specific hypotheses about the effectiveness and reach of airdrops in the U.S. cryptocurrency ecosystem. Key questions we aim to answer include: - What percentage of global cryptocurrency users are U.S. users? - How many active U.S. cryptocurrency users are affected by geo-blocking practices? - Does geo-blocking U.S. claimants result in significant revenue losses for users and the U.S. government? Background on Airdrops Definition of Airdrops What is an Airdrop? A cryptocurrency airdrop is a method of distributing a platform’s native tokens to specific wallet addresses without paying money. Blockchain startups often use airdrops to attract early interest and support for their projects, promote decentralization by expanding token distribution, and reward community participation. [6] Typically, an airdrop involves sending a small amount of tokens to the wallets of active users within a project’s ecosystem. [7] Airdrops typically reward those who stay informed about cryptocurrency developments, participate in social media communities, and meet specific criteria. [8]

How is airdrop eligibility determined?

Blockchain projects use a variety of approaches to conduct airdrops—in most cases, combining several approaches to maximize impact. This tailored approach ensures that airdrops are not only used to distribute tokens, but also support the project's broader goals, such as user acquisition, community building, or market penetration. Projects use a variety of criteria to determine eligibility to receive airdrops, including the following:

Past activity. Teams determine a series of heuristics based on previous on-chain activity to derive the claimable amount for each address. These methods often take into account past interactions with the airdrop protocol. Additionally, these protocols often reward users for prior activity on competitor platforms as part of a strategy known as vampire attacks, which aim to draw users away from competitors.

Early contributors. In almost all cases, airdrops reward early users. Airdrop participants are individually selected to receive tokens based on a number of factors, including reputation and contribution to the project. [9] This approach is a more centralized way to reward early and active user participation, providing targeted rewards to those who have made significant contributions to the community or project. [10]

Snapshots. Existing token holders receive tokens based on their actual token holdings at a specific point in time. [11] A “snapshot” of the blockchain is taken, recording all transactions and balances to determine eligibility for an airdrop. [12]

Forks. A fork is when a blockchain splits into two separate chains, resulting in a new distribution of tokens to users. [13] In most cases, you are eligible for this airdrop if you hold the original tokens of the forked chain. This ensures that the new tokens are widely distributed among existing holders, giving the newly created chain an established, broad user base from the outset. [14]

Raffles. Some airdrops are combined with raffles, where participants have the opportunity to receive raffle tickets by holding tokens, accumulating points, or simply expressing interest. [15]This is typically used when the number of individuals interested in an airdrop exceeds the number of tokens the project plans to distribute. In this case, a draw is held to randomly select a limited number of wallets to receive the airdrop, adding some element of chance to the process. [16]

How do eligible users claim their airdrop?

In most cases, the airdrop claim process follows a similar structure. The airdrop claim smart contract is created by the project team and contains a list of eligible addresses and the associated claimable amount. The user goes to the claim site, proves ownership of the address by connecting a wallet, and then claims the allocated tokens. In some cases, users can also register using other blockchain addresses or accounts on off-chain platforms such as X, Github, and Discord, which may have associated claimable tokens.

In most cases, users must actively claim the tokens. In rare cases, a project may not require any active steps from users, but instead transfer tokens to each recipient in bulk, which is typically done when transaction fees are low. If the airdrop date coincides with the blockchain creation date, tokens may be distributed via airdrop at blockchain genesis, alleviating the need for transfers.

How is an airdrop technically performed?

Executing an airdrop involves multiple technical processes. First, the process involves defining the airdrop parameters and ensuring that all prerequisites are in place. This involves establishing eligibility criteria, determining the total token allocation, specifying a timeline for the airdrop, and finalizing a snapshot date, distribution mechanism, and any associated claims to provide a clear framework for subsequent steps. Additionally, an audit of existing wallets and network activity may be conducted to refine eligibility criteria and align them with the project's goals. [17]

In order to identify eligible participants, a snapshot of the blockchain is taken on a specified date. The system utilizes advanced snapshot tools that capture the state of wallets that meet the predefined criteria and provide a verifiable ledger of recipients. The system filters the data to exclude ineligible addresses, such as dormant wallets or known bots, ensuring that the distribution list is fair and accurate. [18]

At the same time, airdrop smart contracts have been developed to automate the distribution process. These smart contracts play a key role in automating the distribution process, ensuring fairness and transparency while eliminating the need for human intervention and efficiently handling tasks such as managing the list of eligible wallets and allocating the appropriate number of tokens. [19]

Prior to deployment, the smart contracts will undergo a comprehensive third-party security audit to identify and address vulnerabilities and ensure they are resilient to potential attacks. Anti-bot mechanisms, wallet verification protocols, and duplicate claim prevention measures have been integrated into the contracts to provide additional security. [20]

Once the eligibility list and smart contracts are prepared, new tokens will be generated specifically for the airdrop process for distribution. The tokens will then be transferred to the designated distribution wallets under the control of the smart contracts. This ensures that all tokens used for the airdrop are securely managed in a traceable environment. [21]Through the smart contracts, wallets identified during the snapshot can seamlessly receive their allocated tokens. For claims-based distributions, participants will be notified via official communication channels, with detailed instructions to ensure user-friendly access. Throughout the process, blockchain provides an immutable record of all transactions, enhancing transparency and accountability.

The Evolution of Airdrops

Airdrops began as a mechanism to attract users and distribute tokens, but have since evolved into a more complex tool influenced by user expectations, regulatory interpretation, and market behavior.

Initial Phase: Large-Scale Giveaways (2014-2019):

The initial airdrops were a simple token distribution mechanism used to create an initial market and increase project awareness. [22] A typical example is the Aurora Coin issued in Iceland in 2014, which aimed to provide cryptocurrency to all Icelandic citizens as a form of universal access. [23] Users were required to actively claim the tokens. [24] The Aurora experiment marked the beginning of airdrops as a digital asset distribution strategy, although it was limited in terms of attracting users to participate in decentralized ecosystems. Subsequent airdrops from this era involved distributions for platform forks (e.g. Zcash in 2018) and community building (e.g. Stellar’s XLM in 2016)—essentially focused on rapidly expanding the user base rather than meaningfully interacting with the protocol.

Retroactive and Periodic Airdrops (2020-Present):

Following the 2020 Uniswap airdrop, the airdrop distribution model became a more strategic tool, marking a key moment in the evolution of airdrops. When Uniswap found itself under attack from SushiSwap, a Uniswap fork that offered token incentives to users, Uniswap fought back with its own token and airdrops.[25] Uniswap rewards users who previously interacted with the platform with UNI tokens, which grants governance rights within its ecosystem.[26] This successful, retroactive airdrop illustrates the power of airdrops in promoting decentralized governance, positioning them as both a user reward mechanism and a tool for community engagement. [27]

Following the success of Uniswap, airdrops have evolved to reward users based on protocol usage. [28] These changes encourage behavior that directly benefits the project and help build engaged communities. For example, the 2021 dYdX airdrop rewarded users who interacted with the dYdX protocol based on a certain amount of trading volume achieved within a certain time frame. [29]

In addition, projects have begun experimenting with phased or periodic airdrops to allow for feedback on airdrop designs. Optimism is an example of this, which launched its fifth airdrop in November 2024. In this airdrop, the project rewarded users who interacted with at least 20 smart contracts on its hyperchain between March 15 and September 15, 2024, and later evolved to also reward users who frequently interacted with various categories of applications on its hyperchain. [30]

However, as airdrops became more popular, they began to generate unintended consequences, such as “farming,” a practice where participants could game the system to receive tokens from an airdrop. [31] Users began to expect airdrops and interact with the platform simply to qualify for future token allocations, often through superficial or minimal interaction. [32] The problem with this is that airdrop farmers rarely add long-term value, as they stop farming and sell immediately after claiming, and rarely engage with the project afterwards. Interestingly, projects have become savvy and have sometimes used the mining that occurs on the protocol to inflate usage metrics. Overall, over time, mining has diminished the effectiveness of airdrops in driving organic usage, and instead users have sought to exploit these airdrops to extract as much value as possible. [33]

In response to airdrop mining, projects have implemented sybil attack detection procedures before determining airdrop allocations, blacklisting certain addresses from claiming airdrops. However, mining has evolved as quickly as sybil attack filters, leading to a constant game of cat and mouse between projects and airdrop miners.

While innovative thinking has largely driven the evolution of airdrop design, the U.S. legal landscape has been one of the most important factors influencing its trajectory. Projects face scrutiny from regulators such as the U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission (“SEC”) and the Commodity Futures Trading Commission (“CFTC”), which has prompted careful consideration of the structure of airdrops to avoid legal pitfalls.

To reduce the risk of triggering SEC or CFTC action, projects exclude U.S. users[34] or avoid announcing airdrops in advance, thereby reducing any appearance of soliciting investment that could be interpreted as an attempt to create a secondary market that indirectly benefits the issuer. This strategy is reinforced by ensuring that no compensation is received directly or indirectly from recipients.

In response to increasing regulatory pressure, some projects have explored alternative token distribution models. These models include “locked airdrops,” where users lock assets into the protocol in exchange for tokens (the longer they lock, the more tokens they receive);[35] and Dutch auctions, where tokens are gradually released at a decreasing price, allowing participants to purchase at a price consistent with market demand, ensuring a fair and transparent distribution. [36] These models are designed to navigate a complex regulatory environment, but they remain largely untested in the legal environment and may still face scrutiny. Most projects continue to rely on established, low-risk strategies and are cautious about trying new models that have not been legally tested because they could lead to regulatory challenges.

Ultimately, the evolution of airdrops demonstrates a balance between innovation and compliance. As projects strive to attract users and reward loyal participants, they must also navigate a regulatory environment that views many of these strategies as potential securities transactions. This often leads to market distortions and perverse incentives, obscuring the full potential of airdrops and how they can continue to develop organically.

Current U.S. Regulatory Environment

The U.S. cryptocurrency industry is at a critical juncture, facing intense regulatory scrutiny that could stifle innovation and push promising projects overseas. Recent enforcement actions by the U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission and the Commodity Futures Trading Commission highlight a shift toward “enforcement-based regulation,” in which agencies impose penalties and lawsuits on individual projects to set regulatory standards rather than developing clear, consistent rules. This approach, particularly by the SEC, bypasses formal rulemaking requirements and constitutes a blatant overreach by de facto regulating critical emerging technologies that the original Securities Acts of 1933 and 1934 neither contemplated nor addressed. [37]

This strategy has created significant uncertainty and risk, has had a chilling effect on innovation, and has forced many crypto projects and companies to seek clearer regulatory frameworks overseas. This climate of uncertainty has complicated compliance for both startups and established companies, has forced many to seek more favorable regulatory environments abroad, and has raised questions about the long-term legitimacy and transparency of U.S. regulatory practices in this area.

Is Cryptocurrency a Security, Commodity, or Something Else—The Howey Test

The Securities Act of 1933 (the “Securities Act”) and the Securities Exchange Act of 1934 (the “Exchange Act”) grant the SEC the authority to regulate “securities,” a term broadly defined in both statutes through a detailed list of categories, including stocks, bonds, warrants, and “investment contracts.” [38]Notably, the terms “token,” “cryptocurrency,” and “digital asset” do not appear in this definition. The SEC therefore sought to classify these assets as “investment contracts” by applying the four-pronged Howey test.

The Howey test, derived from the 1946 Supreme Court case SEC v. W.J. Howey Co., is the primary standard for determining whether a transaction qualifies as an “investment contract” and, therefore, subject to U.S. securities laws. [39] For an asset to be considered an investment contract, it must involve: (1) an investment of money, (2) investment in a common enterprise, (3) an expectation of profits, and (4) profits derived primarily from the efforts of others. [40] However, applying the Howey test to crypto assets raises new complexities because the test was originally designed to regulate traditional securities, which are typically centralized and rely on an identifiable entity that owes obligations to investors. [41]

Crypto assets themselves often lack the essential characteristics of securities. [42] Under the Howey rule, for a transaction to be considered a security, it is the structure and context of the specific transaction (e.g., an ICO, which raises funds and promises profits), rather than the underlying asset itself. [43] In contrast, many tokens in the secondary market do not establish the necessary legal relationship between an identifiable issuer and individual token holders, which is a key characteristic that distinguishes securities from other assets. [44] In addition, crypto tokens generally do not promise or imply profits associated with ongoing management or entrepreneurial efforts. Therefore, broadly treating crypto tokens as securities may require the introduction of an entirely new concept in securities law: “issuer-independent securities,” a concept that is not supported by any existing legal precedent. [45]

The regulatory ambiguity surrounding crypto airdrops and token classification highlights a major challenge facing the crypto industry: the inability to “come and register.” [46] Existing U.S. securities laws were designed for centralized assets such as stocks and bonds that are issued by identifiable entities with ongoing obligations to investors, making traditional registration requirements ill-suited for decentralized, utility-focused tokens. These laws fail to account for the wide variety of token types—stablecoins, governance tokens, and utility tokens—each of which plays a different role in its ecosystem. For example, utility tokens can grant access to a service, while governance tokens allow holders to participate in decentralized decision-making. Unlike traditional securities, these tokens generally do not promise profit or direct financial returns, challenging the assumption that a digital asset is essentially an investment contract and, therefore, a security.

The diversity of distribution models in the crypto space further complicates the regulatory landscape. Unlike traditional assets that are issued through a single centralized entity, crypto tokens are distributed through mining, forks, airdrops, and ICOs, each of which has very different structures and purposes. [47] For example, mining generates tokens as a reward to network participants rather than through a fundraising investment program. Forks split an existing blockchain into a new token that is distributed to holders for free, while airdrops involve giving away tokens to expand network adoption rather than raising funds. [48] These models generally do not meet the “investment of funds” and “expectation of profit from the efforts of others” criteria under the Howey test, challenging the assumption that a token is essentially a security based solely on its issuance.

The real issue is the nature of the transaction, not the tokens themselves. The Howey test, which is used to determine what constitutes an investment contract, focuses on the circumstances of the transaction—the promises, relationship, and expectations of the parties to the transaction, not just the asset. [49] For example, if a token is sold to fund a project under an investment plan, it could be considered a security. But the same token would not necessarily become a security if it were later freely traded on a secondary market without any accompanying contractual promises or obligations. This distinction reflects the core legal principle that the transaction, not the asset, determines whether an investment contract exists. As with the orange grove in the landmark Howey case,[50] the asset itself (the tokens in this case) does not become an investment contract simply because it is sold. It is the circumstances and nature of the transaction that determine whether the transaction itself qualifies as an investment contract under Howey.

Traditional registration is impractical in this context. Cryptocurrency companies often face the dilemma of either trying to structure their products to avoid triggering securities laws, which carries with it considerable legal uncertainty and costs, or confining to the United States entirely to avoid regulatory issues. Registering as a security would impose a disproportionately high compliance burden because the existing framework requires that every token transaction be treated as a security sale. This requirement is not only unfeasible for lean crypto startups operating decentralized networks, but also inconsistent with the nature of blockchain ecosystems, where tokens often function differently than traditional securities. Current regulatory frameworks do not take into account the highly diverse functionality and distribution of tokens in blockchain ecosystems, often used as tools within the network rather than as investment vehicles. Therefore, a clear, updated regulatory approach is critical - distinguishing between financing transactions (which may be subject to securities laws), secondary market token transactions, airdrops, mining, etc. - all of which should be treated differently.

As we explore the complex landscape of cryptocurrency regulation, it is clear that it is critical to distinguish between different types of crypto activities. This distinction is particularly important when considering airdrops, which have unique characteristics that are different from traditional securities offerings.

Airdrops are more similar to these examples

Crypto airdrops are more similar to (i) loyalty programs or (ii) memberships than to traditional securities or stock distributions. Loyalty programs are designed to incentivize customer retention and reward customers for repeat purchases or continued participation in brand activities. Such programs include airline frequent flyer programs or credit card rewards. Membership programs, on the other hand, often offer exclusive benefits, such as access to private events, discounts, or premium features, with a focus on creating a sense of belonging and exclusivity for participants. Despite these functional differences, the SEC often evaluates airdrops under the framework of the “free” stock case,[51] treating them as free stock distributions and subjecting them to securities regulation. This regulatory approach fails to take into account the unique nature of airdrops, which are more appropriately analogized as mechanisms for fostering engagement and building community than equity distributions.

i. Loyalty Programs

Frequent flyer miles and credit card points, like cryptocurrency airdrops, are stored value programs that incentivize user loyalty and engagement. Miles and points can be redeemed for flights, upgrades, or meals, encouraging user loyalty to a particular brand, just as airdrops leverage tokens as a means of rewarding loyalty or encouraging engagement with the platform. Both approaches prioritize engagement and ecosystem growth, but neither is primarily intended to provide a return on investment.

Companies often offer loyalty programs, such as airline miles or credit card points, without triggering the *Howey* test. Notably, the SEC has not yet taken enforcement action against credit card points or airline miles, further underscoring their nature as consumer incentives rather than investment vehicles. Credit card points fall under the jurisdiction of the Consumer Financial Protection Bureau (“CFPB”) and the Department of Transportation (“DOT”) as they apply to airlines. [52] Therefore, there is a strong argument that airdrops should not be treated differently from these well-established loyalty programs, which companies often employ to build loyalty and drive engagement.

While tokens differ from points and miles in that they have secondary markets and can be used for governance, it is important to consider that the existence of secondary markets alone does not necessarily classify tokens as investments. As with gift cards, the transferability of tokens serves primarily to increase consumer utility and flexibility rather than to signal investment intent. Furthermore, allowing token holders to participate in governance is akin to joining a voting customer advisory board or club, which does not convert these tokens into securities, but rather fosters greater user engagement and community commitment. The core purpose of token airdrops is very similar to traditional loyalty programs, incentivizing usage and loyalty to the platform. Regulatory precedent surrounding similar features supports this interpretation, underscoring the need to view airdrops as an extension of consumer loyalty strategies.

Credit cards such as the Chase Sapphire Preferred exemplify this model, offering points that can be redeemed within a flexible rewards incentive structure to drive repeat usage. [53] In this model, accumulated points can be used for a variety of services and products within the Chase ecosystem, as well as transferred to a wide range of partners. [54] This flexibility enables cardholders to choose from a variety of redemption options, including different airlines and hotel chains, thereby maximizing the utility and potential value of their points to meet a wider range of preferences and needs. Similarly, Aave’s Merit program mirrors loyalty programs, rewarding users with token allocations based on meaningful contributions to the protocol, such as governance participation or liquidity provisions. [55] These tokens function similarly to points, creating an open-loop incentive structure that encourages continued participation and reinforces users’ commitment to the platform, but at the same time allows users to transfer points to take advantage of better deals. While regulatory frameworks often conflate airdrops with securities, their true similarities are closer to loyalty programs, as both primarily allocate value to enhance engagement rather than provide financial returns.

For tokens with stable value, such as stablecoins, the analogy is even stronger. Just as loyalty programs reward users with points for referring friends, airdrops similarly incentivize user acquisition and ecosystem participation. Rather than speculation, these mechanisms lay the foundation for long-term engagement.

Ultimately, loyalty programs and cryptocurrency airdrops share a core principle: using value distribution to deepen user engagement, foster community growth, and enhance ecosystem sustainability. Both demonstrate how incentives can be aligned with utility to drive meaningful engagement without relying on speculative investment dynamics.

ii. Memberships

Whether in traditional industries or digital ecosystems, membership programs are designed to foster loyalty and engagement by providing exclusive, useful benefits. For example, NFL fan memberships grant privileges such as priority ticket purchases, discounts on team merchandise, VIP event invitations, and behind-the-scenes content, creating a sense of community and deepening connections to the team’s ecosystem. [56] The value of these rewards derives from their direct connection to the platform, rather than from external resale opportunities. Notably, the SEC has determined that such membership programs, such as the Los Angeles Rams Fan Club, are not covered by the Securities and Exchange Act. [57] In a no-action letter, the SEC clarified that these memberships are purchased for entertainment and consumption, rather than as investments with the expectation of profit, further distinguishing them from securities. [58]

Similarly, airdrops in the cryptocurrency space serve a similar purpose. For example, the Stargate Finance airdrop rewards active participants with free tokens that can be used within the ecosystem. [59] This strategy not only incentivizes participation and loyalty, but also supports the development of new projects within the platform. Both examples highlight the intrinsic value of rewards that are designed to strengthen participation and commitment within a particular ecosystem, prioritizing utility and community involvement over external financial returns.

Why Airdrops Do Not Qualify as Securities Transactions under Howey

Airdrops should not be classified as securities transactions. The SEC’s position is that airdropped tokens constitute investment contracts and are therefore unregistered securities. This position is reflected in many of the enforcement actions and informal guidance detailed later in this report. [60] However, unlike traditional securities offerings that are designed to raise capital, airdrops are often designed to promote network participation by distributing tokens for free. [61] Therefore, applying securities laws to airdrops is a mischaracterization of their purpose and places an unnecessary regulatory burden on many blockchain projects.

Under the *Howey* test, airdrops fail to meet key criteria:

No investment of funds: The core element of the *Howey* test is “investment of funds” with the purpose of generating income or profit, thereby establishing a direct link between the invested funds and the expected return. [62] However, in the case of airdrops, the distribution of tokens does not require any financial consideration from the recipient. Minimal actions such as registering an account do not constitute a financial investment, which makes airdrops more closely related to promotional activities than securities transactions.

Lack of common cause: For an arrangement to qualify as a security, it must involve a “common cause,” which requires a common financial relationship between the participants and the pooling of financial resources between the participants. This can manifest itself as horizontal commonality, where investors pool their resources into a single enterprise, tying their fates to one another[63], or vertical commonality, where the financial success of the investors is directly tied to the efforts or success of the sponsor or issuer. [64] However, airdrops lack the element of common cause because they distribute tokens independently, with no common financial interests or interdependent risks between recipients. With respect to horizontal commonality, airdrops distribute tokens directly to individual recipients without the recipients having to invest any money, effort, or resources. There is no pooling of assets or sharing of risk because the fate of each recipient is completely independent of the others. With respect to vertical commonality, the recipients do not have to invest because they do not pay any money, and therefore cannot have any dependency on the sponsor because there is no investment in the first place.

No expectation of profit: Securities generally imply an expectation of profit from the efforts of the sponsor or a third party. In contrast, airdropped tokens are typically intended for consumption purposes within the platform, rather than for investment purposes. Tokens may grant users access to platform-specific features in order to participate, such as voting on governance proposals or paying for services. While some recipients may choose to sell them, any potential profit comes from market forces, not active promotion by the issuer, eliminating this criterion of the *Howey* test.

No reliance on issuer effort: Recipients of airdropped tokens do not rely on the actions of the issuer to increase the value of the tokens. Unlike securities, which typically rely on ongoing management to maintain or increase their value, airdropped tokens fluctuate based on external market factors, further distinguishing them from securities. Additionally, any effort comes entirely from the individual receiving the airdropped tokens, not from the platform or project itself.

Distinguishing Past Precedents from Modern Airdrops

The “Free” Stock Case of the 1990s/2000s

In the legal debate over whether airdrops qualify as securities, it is important to distinguish them from the “free” stock cases of the late 1990s and early 2000s during the “dot-com bubble.” At the time, the SEC targeted Internet companies that distributed stock to attract web traffic, arguing that these giveaways were illegal “sales” of securities because they were not registered or exempt. [65] The express purpose of these free distributions was to generate profits for the promoters and to allow the issuers to gain financial benefits. These companies often engaged in deceptive practices, using the lure of free stock to trick investors into providing personal information or actively promoting these businesses, a practice that was ultimately curbed by strict enforcement actions by the SEC. [66] In addition, the securities were expected to be sold in the secondary market, suggesting that these free securities were an investment.

The SEC’s analysis suggests that these were not true free giveaways, but rather transactions in which stock was exchanged for value. [67] By referring new users or drawing public attention to the company, these companies received significant benefits from recipients who effectively acted as marketing agents. [68] The SEC considers these transactions to be “sales” of securities because there was an exchange of value under the Securities and Exchange Commission Act. [69]

There are several key differences between token airdrops and “free” stock cases in determining whether there was an exchange of value:

No quid pro quo: In “free” stock promotions, rewards are explicitly promised, and users refer others in exchange for stock, leading to widespread spam. In contrast, cryptocurrency airdrops often lack such a quid pro quo; many recipients are rewarded simply for their active participation, without knowing in advance that their participation would result in a token distribution. Without a quid pro quo, there is no exchange of something of value.

Lack of consideration: In the “free” stock case, the consideration given by participants includes personal data such as email addresses and social security numbers, which have intrinsic value because they can be used by the issuer for targeted marketing and other monetization strategies. It is logical that this personal data can be considered “consideration” under securities laws because it provides economic value to the issuer. In contrast, in an airdrop, the only requirement for participants is to provide a public wallet address. The value of these addresses is different because:

Public information: Public wallet addresses are already accessible on the blockchain and can be easily obtained by anyone. Their public nature means that they do not provide exclusive value to the airdrop issuer.

No personally identifiable information: Unlike email addresses or social security numbers, public wallet addresses should not be classified as personally identifiable information from a securities law perspective. They do not provide a way to directly identify, contact, or locate an individual, thus reducing their usefulness for purposes other than transaction verification on the blockchain.

Given these characteristics, a public wallet address does not constitute valuable consideration under securities laws.

Independent Utility of Tokens: Tokens differ significantly from stocks in terms of functionality and purpose. While the value of stocks is primarily determined by market performance and company management, tokens often have intrinsic utility that transcends speculative purposes. For example, tokens may provide direct, tangible benefits such as platform access and participation. This utility is integral to the design and purpose of tokens, emphasizing that their primary purpose is not to be resold on secondary markets. Therefore, tokens should not be viewed through the same legal lens as stocks, as their primary value and purpose are fundamentally different.

Thus, while both free stock and airdrops can be promotional tools used by entities to expand their user base or reward loyalty, the underlying legal interpretations of these mechanisms differ significantly due to the investment of funds and expectations of profit, which are generally not directly applicable to cryptocurrency airdrops.

Morrison Extraterritoriality: Offshore Transactions Should Not Be Subject to SEC Jurisdiction

The 2010 U.S. Supreme Court decision in Morrison v. National Australia Bank fundamentally redefined the scope of U.S. securities law, limiting its application to transactions within the United States. [70] The decision established what is commonly referred to as the “transaction test,” which limits the extraterritorial effect of U.S. securities. [71] Specifically, the Court ruled that Section 10(b) of the Exchange Act applies only to transactions in securities listed on domestic exchanges and to domestic transactions in other securities. [72] This precedent is particularly relevant to the practice of distributing cryptocurrency airdrops, which are often global and not limited to U.S. jurisdiction.

Cryptocurrency airdrops typically involve the distribution of digital tokens to a wide range of international recipients, often without any exchange of currency. These distributions do not necessarily involve U.S. markets unless the tokens are subsequently traded on a U.S. exchange. Even so, the raw act of airdropping tokens to non-U.S. recipients (who do not transact on U.S. soil) falls outside the scope of the Morrison definition.

Given these factors, applying U.S. securities laws to offshore airdrops would not only exceed the territorial limitations set forth in Morrison, but would also mischaracterize the nature of these transactions under the securities laws. The argument that offshore airdrops should not be subject to U.S. securities laws is therefore both legally supported by the Morrison decision and consistent with fundamental principles of securities regulation.

The History of Enforcement and Its Impact on Airdrops and the Cryptocurrency Industry

The history of enforcement and regulation of the U.S. cryptocurrency industry reveals a fragmented regulatory approach that has created significant confusion and inconsistency, particularly with respect to airdrops and token classification. The next section dives deeper into how shifting regulatory enforcement and evolving securities law interpretations have created an uncertain and sometimes contradictory regulatory environment for cryptocurrency projects dealing with airdrops.

Pre-2017: *Regulators Begin Scrutiny and Enforcement of Initial Coin Offerings

Initially, as the cryptocurrency industry began to develop, regulators such as the SEC and CFTC took a hands-off approach. It was not until the popularity of ICOs and the growing visibility of cryptocurrencies did the SEC begin to signal its regulatory intent.

SEC’s DAO Report

The SEC’s DAO Report, published in 2017, marked the SEC’s first major regulatory action in the crypto space.[73]By applying the *Howey* test to tokens distributed by decentralized autonomous organizations (“DAOs”), the SEC highlighted that many such tokens could be considered securities.[74]The report was the SEC’s “bottom line” in the “cryptocurrency space.” ” formally notified the digital asset industry that participants needed to comply with U.S. securities laws, regardless of whether the company was located in or outside the United States.[75] Rather than providing a clear regulatory framework, the SEC took an enforcement-led approach, evaluating token sales based on their structure and investor expectations. This approach increased regulatory uncertainty, particularly impacting companies using airdrops, as they had to carefully navigate these evolving and unclear standards.

2018-2020: The Beginning of Enforcement

Tomahawk – “Free” Token Distribution Case

The real turning point for airdrops came with the SEC’s action against Tomahawk Exploration LLC in August 2018.[76] In this case, the SEC argued that if tokens distributed through bounty programs qualified as securities under *Howey*, then those tokens could violate the securities law test.[77] Tomahawk’s “Tomahawkcoins” were given away to recipients who provided promotional services, which the SEC considered to be a violation of section 5 of the Securities Act. SEC’s Investment Contracts Framework Subsequently, in April 2019, the SEC made its first direct reference to airdrops, issuing a non-binding guidance document titled “Framework for the Analysis of ‘Investment Contracts’ for Digital Assets” (the “Framework”). [80] The Framework purports to clarify how digital assets are classified as securities under the *Howey* test. However, it leaves a number of gray areas unanswered—such as what constitutes an “ongoing management effort” (Section 4). Specific to airdrops, the Framework suggests that even “free” token distributions can be considered securities offerings if they serve to promote the economic benefit of the ecosystem, subjecting many promotional activities to regulatory scrutiny. [82] While the Framework does not provide specific guidance on airdrops, projects that have promoted adoption of digital asset networks through airdrops are beginning to assess whether the actions required for third parties to receive and claim assets can be considered “investments of money” under the Howey test. [83] While the Framework provides some useful guidance, it also introduces a complex, fact-specific analysis for issuers and platforms, blurring the line between securities and commodities in the digital asset space. [84] This ambiguity has led to an increase in enforcement actions and increased scrutiny for legitimate projects as they attempt to comply with the SEC’s evolving and ambiguous standards. [85]

SEC Actions Against Kik, Telegram, and Ripple

While these following cases do not directly involve airdrops, their significant impact on the broader cryptocurrency market indirectly impacts the airdrop strategy. From 2019 to 2020, the SEC significantly shifted its regulatory focus, bringing enforcement actions against Kik, Telegram, and Ripple against major platforms, deepening its focus on a market previously characterized by regulatory ambiguity. In these cases, the SEC successfully blocked Telegram’s $1.7 billion ICO[86] and Kik’s $100 million ICO[87], arguing that the tokens involved constituted unregistered securities. The courts sided with the SEC, confirming that these token offerings were essentially investment contracts and therefore subject to the federal securities laws. In addition, both cases highlighted the SEC’s jurisdiction over foreign token sales that could result in U.S. resales, expanding the international applicability of U.S. securities regulations. Kik and Telegram sent a clear message that token offerings associated with ecosystem development may be classified as securities. The lawsuit against Ripple Labs alleging that its sale of XRP tokens constituted an unregistered securities offering further exacerbated these regulatory uncertainties, leading major exchanges to delist XRP, which in turn exacerbated market volatility. [88]

The SEC’s aggressive actions against Kik, Telegram, and Ripple have profoundly impacted the cryptocurrency market and significantly reshaped the airdrop strategy. In these enforcement actions, the SEC was well positioned to classify token offerings as unregistered securities. As the SEC steps up its scrutiny, projects utilizing airdrops must carefully consider how and why they distribute tokens to avoid similar legal challenges. The regulatory ambiguity left by the SEC’s actions and guidance means that airdrops, which have traditionally been viewed as a benign method of increasing user engagement and network participation, now require careful evaluation of whether any part of the airdrop process can be construed as an “investment of money” under the Howey test. This includes evaluating whether the steps a participant takes to receive an airdrop can be viewed as an investment of effort that is likely to receive a return, subject to the ongoing efforts of the token issuer.

As a result, the fallout from the SEC’s high-profile cases has expanded the scope of what may be considered a security, making airdrops murky. This regulatory environment has forced airdrop strategies to evolve in a more cautious and legally nuanced manner, such as blocking U.S. users from qualifying to participate in airdrops. Projects must navigate these murky waters, adjusting airdrop strategies to minimize legal risk while working to achieve their outreach and network growth goals under the shadow of possible SEC enforcement.

2021-2022: Adapting to Ambiguity and Direct Attacks on Airdrops

Blocking U.S. Users and Using VPNs

By 2021, the regulatory environment for crypto has tightened as the CFTC and SEC have stepped up legal action against unregistered offshore exchanges that offer crypto derivatives. Both agencies have stated that it is illegal under U.S. law for U.S. users to trade on these platforms due to the increased risks and lack of investor protection. [89] Under increasing regulatory pressure, major offshore exchanges such as FTX and Binance announced measures to ban U.S. traders, including mandatory know-your-customer (“KYC”) checks, IP address blocking, and geolocation filters designed to prevent Americans from accessing their accounts on their websites. [90]

However, despite these restrictions, many U.S. traders circumvented these barriers and continued to trade on platforms such as FTX and Binance. [91] With no other options, U.S. traders began using virtual private networks (“VPNs”) to mask their location and, in some cases, provide misleading information during KYC verification. The minimal verification requirements of some platforms (such as simple email addresses and self-reported country) created exploitable vulnerabilities. However, regulators took notice of such workarounds.

This period also marked a shift in the approach to airdrops. Following Uniswap’s massive token distribution on September 16, 2020[92] (the last major airdrop not subject to geo-blocking), subsequent projects began to increasingly adopt geo-blocking strategies to exclude U.S. participants. Airdrops such as 1inch[93] on December 25, 2020, dYdX[94] on September 8, 2021, and ENS[95] on November 9, 2021 all exemplify this compliance initiative. These examples illustrate how crypto projects are evolving their strategies to adapt to complex international regulations and remain compliant with U.S. securities laws, highlighting legal security in an evolving regulatory environment.

Gary Gensler Sworn in as SEC Chairman

Tensions between U.S. regulators and cryptocurrency companies escalated significantly after Gary Gensler was sworn in as SEC Chairman on April 19, 2021.[96] Gensler was known for his positive views on cryptocurrencies during his tenure at MIT,[97] but changed his stance during his tenure in office. [98] He began describing the crypto industry as a “Wild West,” advocating for increased regulation and frequently warning that many tokens could be classified as unregistered securities. [99] By 2022, Gensler had hardened his approach, claiming that the “vast majority” of the nearly 10,000 tokens on the market were likely securities. [100] Frustrated with Congress’s slow response to legislation, Gensler aggressively pursued a “regulatory enforcement” strategy, issuing Wells Notices and filing lawsuits against major exchanges such as Binance and Coinbase, which sent shockwaves through the industry. [101]

Hydrogen – The Airdrop Case

In SEC v. Hydrogen Technology Corp. (September 2022), the SEC argued that token distributions through airdrops, bounty programs, and employee compensation could be considered unregistered securities offerings, thereby expanding the scope of securities laws to include non-monetary distributions. [102] Specifically, the SEC argued that these methods create a “monetary investment” (provision 1 of the Howey test) because airdrop recipients typically must actively claim the tokens and sometimes pay gas fees, which implies a financial commitment. [103] This evolving interpretation suggests that the traditional notion of “free” airdrops is outdated, with the SEC viewing them as free announcements that require active user participation and potential financial expenditure. The ambiguity in the drafting of the complaint raises questions about whether the SEC is truly distinguishing between bounty programs and airdrops, adding to industry uncertainty about the standard to be followed.

In addition, the SEC argues that the promotional activities or “merchants” surrounding the distribution of tokens indicate that the tokens are being offered with the “expectation of profit,” thereby classifying them as securities. [104] This action underscores the SEC’s position that labeling a token distribution as an “airdrop” or “bounty” does not exempt it from securities regulation.

2023-Present: Focus on Big Players

Throughout 2023, the SEC has set a record for crypto-related enforcement actions, expanding its focus from centralized exchanges to decentralized organizations and protocols. With its February 2023 actions against Terraform Labs and Do Kwon, the SEC made clear that the agency was expanding its scope to stablecoins and other crypto products that have not traditionally been considered securities.[105] This shift signaled the agency’s intent to dominate the industry as the primary enforcement mechanism and propelled it to pursue some of the industry’s largest players, including Coinbase and Binance. [106]

SEC Action Against Justin Sun, Tron, and BitTorrent – Airdrop Case

In March 2023, the SEC charged Justin Sun and his three wholly owned companies, Tron Foundation Limited, BitTorrent Foundation Ltd., and Rainberry Inc. (formerly BitTorrent), with engaging in the unregistered offer and sale of the crypto asset securities Tronix (TRX) and BitTorrent (BTT). [107] The defendants conducted multiple airdrops to distribute BTT to TRX holders and participants in various online events. These events promoted the growth of the BitTorrent and TRX ecosystems, increased demand and trading volume for TRX, and introduced BTT to a broad audience. The case is currently pending in the United States District Court for the Southern District of New York.

In April 2024, the SEC amended its complaint, asserting jurisdiction over Justin Sun and his related activities in the United States. [108] The amendment highlighted Sun’s extensive travels across the United States and his promotional activities for Tron, BitTorrent, and Rainberry, including livestreams from his San Francisco office. These details highlight the SEC’s commitment to regulating foreign digital asset operations involving U.S. residents or territories, even if the connection is minimal. The case stems from a foreign offering, underscoring the SEC’s aggressive enforcement of foreign entities with U.S. ties and warning airdrop projects to carefully evaluate compliance strategies, including shielding U.S. users.

Fleeing the United States

Amid the onslaught of enforcement actions, lawsuits, and overall industry uncertainty, news reports began to emerge from around March to August 2023 about crypto projects expressing concerns and looking to move overseas. [109] Companies expressed frustration with what they viewed as unclear and restrictive U.S. regulatory guidance, which made it challenging to do business in the country. While companies expressed hope for a clearer regulatory environment, the influx of more enforcement actions did not provide any relief.

Ripple Labs Decision and Terraform Labs Decision—Contradictions in Court Decisions

On July 13, 2023, Judge Analisa Torres of the United States District Court for the Southern District of New York achieved one of the most significant legal victories in the crypto space, a defense that the crypto community has long debated. In ruling on the motion to dismiss in the *Ripple* case, Judge Torres distinguished between institutional sales and programmatic sales, finding that programmatic sales by retail investors did not qualify as securities offerings. [110] She reasoned that buyers could not have reasonably expected that XRP sales would be used to enhance the XRP ecosystem and drive up its price, and therefore failed to meet the third and fourth prongs of *Howey*’s* test. [111] In addition, the decision laid the foundation for arguments to distinguish between primary and secondary market sales, which impacts the securities liability faced by exchanges and platforms.

However, less than a month later, on July 31, 2023, in the same district court, Judge Jed S. Rakoff took a very different position from Judge Torres on the distinction between institutional and programmatic sales, denying Terraform Labs’ motion to dismiss because he classified all transactions as securities offerings. [112] While the facts of the two cases were strikingly similar, the rulings were very different, highlighting the great uncertainty and lack of clarity not only among U.S. federal regulators but also among federal courts on how to classify crypto transactions.

CFTC Actions Against Opyn, ZeroEx, and Deridex – Efforts to Stop Attacked U.S. Persons

In September 2023, the CFTC simultaneously brought and settled cases against DeFi platforms such as Opyn, ZeroEx, and Deridex, which faced charges related to illegal derivatives trading. [113] The CFTC’s enforcement actions against DeFi platforms highlight the agency’s intent to apply its established regulatory framework for derivatives and margin trading to the decentralized finance space. These actions underscore the CFTC’s position that simply blocking U.S. IP addresses is not sufficient to exclude U.S. users from DeFi protocols. However, the agency has yet to clarify what measures would be sufficient, leaving DeFi platforms in a state of flux and uncertainty and exacerbating confusion among projects planning airdrops about how to effectively comply.

Beba LLC and DeFi Education Fund v. SEC—A Proactive Airdrop

Given the SEC’s lack of clarity on airdrops and ongoing enforcement actions against a variety of platforms, companies have been forced to proactively address regulatory uncertainty in their own ways. Beba LLC (“Beba”), a small clothing company based in Waco, Texas, that sells handmade luggage and accessories through its online store, has partnered with the DeFi Education Fund (“DEF”), a nonpartisan research and advocacy organization based in Washington, D.C., to file a pre-enforcement lawsuit against the SEC. The lawsuit seeks court protection prior to Beba’s planned airdrop of its $BEBA tokens, seeking to clarify the regulatory uncertainty surrounding the plan. [114]

Beba created $BEBA tokens and distributed them via free airdrops without any monetary consideration. However, the company postponed its second planned airdrop due to the SEC’s weak enforcement approach and an overall lack of clear guidance on which tokens and actions fall under the SEC’s jurisdiction. The plaintiffs are seeking declaratory and injunctive relief, arguing that the SEC’s regulatory stance on digital assets exceeds its statutory authority and violates the Administrative Procedure Act (“APA”) because the agency has adopted a sweeping crypto policy without engaging in an official rulemaking process. [115] Specifically, it seeks a declaration that the $BEBA token airdrop was not a securities transaction and that the $BEBA token itself was not an investment contract. This clarification would provide Beba with legal certainty, allowing them to continue their business operations without the imminent threat of an enforcement action.

While the SEC claims that it has “not yet taken any action against Beba and that, if and when it does, Beba will have an opportunity to defend itself,”[116] this claim appears to be out of touch with reality. Small companies have been forced to close under the weight of the SEC’s unexpectedly harsh enforcement actions, which often leave businesses like Beba unprepared and unable to recover. As such, this lawsuit also seeks to challenge the SEC’s overreach and to establish that its enforcement strategy and interpretation of digital asset regulations have exceeded its statutory authority. Thus, by targeting allegations of APA violations, the lawsuit has the potential to provide much-needed clarity on the SEC’s role in the airdrop and, more broadly, its position in the digital asset industry. The case is currently pending in the United States District Court for the Western District of Texas.

The U.S. cryptocurrency compliance landscape has become so chaotic and confusing that it is nearly impossible for entrepreneurs to navigate effectively. In a September 17, 2024 letter, a bipartisan group of congressional members led by Rep. Tom Emmer urged the agency to abandon its reliance on “enforcement regulation” and highlighted concerns about the SEC’s stance on airdrops, noting that the agency’s failure to clarify how airdrops (often used to distribute tokens across decentralized networks) should be treated under securities laws has left projects and investors in a state of regulatory uncertainty. [117]

For the United States to maintain its global leadership in technology and innovation, a shift toward proactive, clearly defined, and balanced regulatory policies is urgently needed. Only with such clarity can we foster a thriving, compliant, and innovative crypto ecosystem that benefits the U.S. market and consumers.

Projects are blocking Americans

In addition to seeking to reduce ties to the United States, many crypto projects are actively blocking U.S. users from accessing their platforms using a variety of means to appease U.S. regulators. Because crypto products are often decentralized and permissionless, fully complying with regulations designed for traditional centralized businesses is both technically challenging and financially onerous. [118]

Due to this environment, crypto projects have been forced to use a variety of methods to restrict U.S. users.

Geo-blocking or geo-fencing: Geo-blocking involves creating a virtual boundary (a fence) around a specific geographic area so that users in those locations cannot access a service or online content. [119] Websites can use a variety of methods to detect your location. It can use your Internet Protocol ("IP") address to detect your approximate location, check which country handles your Domain Name System ("DNS") service, determine the location of your payment data, or even determine the language you use to shop online. [120]

IP address blocking or IP blocking: IP blocking is a geo-blocking technique that restricts access to an online platform based on a user's specific IP address. Every internet device has its own unique IP address, so the network can keep track of such addresses. When someone with a blocked IP address tries to access the platform in the future, the platform's security system (firewall) can block access. [121]

VPN blocking: A VPN allows you to encrypt your internet connection so that your traffic and IP address remain unknown. [122]It is used to maintain your privacy and security. VPN servers often assign the same IP address to multiple users to enhance privacy, but this shared use can cause websites and services to monitor a single IP for high traffic or diverse activity. As a result, websites may block the address to restrict access. [123]VPN blocking is often used in conjunction with geo-blocking as a preventative measure.

KYC processes: Platforms may also have KYC checks and compliance programs, which help detect illicit financing and money laundering. Additionally, some projects require users to confirm their non-US identity by signing a message with their wallet. Such processes can also be used to verify and block US persons from accessing the platform by checking the identity of the user. [124]

Agencies have not yet clarified what actions would be sufficient to block U.S. users

While many projects have attempted to make genuine efforts to block U.S. users, regulators such as the SEC and the Commodity Futures Trading Commission have yet to provide clear guidance on what actions would be sufficient to block U.S. users. The ambiguity around compliance leaves projects uncertain about what steps they should take. This creates a cycle of self-censorship where projects choose to limit their scope to avoid the risk of legal consequences, leading to a diminished presence of U.S. companies in the global crypto market.

For example, the CFTC brought enforcement action against DeFi platform Opyn, alleging that it offered an illegal leveraged and margined digital asset retail offering through its platform.[125] However, despite Opyn’s efforts to geo-block U.S. users, the CFTC deemed the measure insufficient and did not clearly define what constitutes sufficient compliance. [126] CFTC Commissioner Summer K. Mersinger specifically criticized the agency in its statement of opposition to the enforcement action:

“However, by lacking a transparent notice and comment process for rulemaking, the Commission has created an impossible environment for those who want to comply with the law, forcing them to either close U.S. markets or exclude U.S. participants.”[127]

Operational Challenges and Compliance Costs

While the regulatory environment forces crypto projects to adopt various restrictions to avoid U.S. enforcement actions,[128] these requirements not only create significant operational challenges, but also increase costs and legal risks for companies. Many teams must choose between developing custom geo-blocking solutions in-house or relying on third-party providers such as Vercel.[129]While third-party services are more efficient and often more cost-effective, they increase reliance on external providers for data accuracy and reliability, which can lead to compliance risks and system vulnerabilities.

For example, anecdotally, one project we interviewed experienced a major compliance scare because third-party geo-blocking data incorrectly indicated access from restricted regions, raising concerns about the effectiveness and accuracy of third-party solutions. While this issue was later determined to be a mistake, it highlights the operational risks and uncertainties inherent in relying on external data providers for compliance. Liability for any violations ultimately remains with the project, not the third-party provider,[130] meaning that enforcement actions could still target crypto companies for access violations even if a third-party service caused the issue.

This stringent compliance requirement not only increases operational complexity and costs, but also creates significant legal risk, as projects are subject to strict liability for any sanctions or unregistered securities law violations. In this context, strict liability means that companies could face severe financial and reputational consequences even if they had no intention of violating compliance regulations. This heightened compliance burden and risk hinders innovation and complicates efforts to safely expand the crypto ecosystem within the United States, further illustrating the adverse impact of enforcement regulation on the industry as a whole.

In addition to excluding U.S. users, projects are advised not to encourage the use of VPNs, as this could be interpreted as an attempt to circumvent U.S. regulations. Projects that explicitly direct U.S. users to use VPNs could come under scrutiny from the SEC, as seen in cases where organizations have faced penalties for perceived circumvention of regulatory controls. By explicitly stating that airdrops were not available to U.S. persons and making good faith efforts to actually restrict U.S. persons, the projects reinforced their argument that the distributions were not subject to U.S. jurisdiction.

Enforcement Regulation Violates the Administrative Procedure Act

The agency’s use of enforcement regulation, particularly regarding airdrops, conflicts with principles of the Administrative Procedure Act, which requires a structured and transparent rulemaking process. [131] The SEC relies on litigation rather than formal rulemaking to enforce securities laws in an unpredictable and often retroactive manner. [132] This creates an unstable regulatory environment, as demonstrated by the U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission’s (SEC) high-profile case against Ripple Labs, in which the SEC alleged that Ripple’s XRP token, a utility token used for international payments, constituted a security, even though XRP holders lacked a financial connection to Ripple and many were unaware of the company’s connection to the underlying token. [133]

Under the APA, federal agencies must follow clear procedures when developing new regulations, including public notice of proposed rules and public comment periods. [134] These procedural requirements are designed to ensure democratic accountability, allow for public and industry expert input, and allow for thorough deliberation before finalizing rules, thereby ensuring that policies are clear, predictable, and fair. [135] For example, in the Ripple case, the lack of prior, public rules governing the SEC’s crypto-securities policy led to considerable uncertainty. [136] Ripple has been operating for nearly a decade, and it has been argued that XRP does not meet the criteria for a security because of its structural similarity to Bitcoin and Ethereum, both of which the SEC has previously stated are not securities because of their decentralized structures. [137] The SEC’s enforcement actions without clear, pre-existing guidance have left Ripple and many other token projects mired in an unpredictable regulatory environment. [138]

In addition, enforcement-based regulation undermines procedural fairness by setting unpredictable standards through isolated cases rather than a consistent public rulemaking process. This arbitrary approach undermines the credibility of institutions and erodes trust in the industry. Without clear, forward-looking rules, smaller companies and developers could face greater compliance burdens that could severely impact their ability to operate. Selective prosecution not only lacks transparency but also appears arbitrary, particularly as Bitcoin and Ethereum have been allowed to operate without such regulatory scrutiny. [139] This approach allows institutions to “pick winners and losers,” disadvantaging smaller and newer projects that enter the market without clear rules while benefiting first movers from regulatory certainty. [140]

Economic Impact

As the cryptocurrency landscape continues to evolve, understanding the scale of U.S. participation and the financial impact of restrictive policies will be critical for future regulatory decisions. Our goal is to quantify the impact of geo-blocking policies on cryptocurrency airdrops for U.S. residents and assess the broader economic consequences of these policies. Our analysis estimates the number of cryptocurrency holders in the U.S., assesses their level of participation in airdrops, and describes the economic and tax losses that geo-blocking could cause.

To drive economic impact, we compiled a sample of 11 geo-blocked airdrops and 1 non-geo-blocked airdrop for our control. We handpicked these airdrops due to their significance in the crypto ecosystem and the fact that they were all on the Ethereum blockchain, ensuring a significant, streamlined, and efficient data collection process. These also happen to be among the most successful projects in crypto. We first estimated the number of Americans impacted by crypto geo-blocking policies. We then calculated the number of active wallet addresses controlled by Americans. Next, we determined the number of recipients for our sample, the total revenue, and the median amount per recipient of that airdrop. Using this data, we estimated the total potential tax revenue lost by U.S. residents and the U.S. government as a result of geo-blocked airdrops in our sample and another sample from CoinGecko.

U.S. Participation Rates

It is estimated that there are **18.4 million to 52.3 million cryptocurrency holders** in the United States, and **920,000 to 5.2 million monthly active U.S. users in 2024 will generally be affected by geo-blocking policies, including airdrops and reduced participation in project usage.

Table 1: Estimated percentage of US active addresses in 2024

Based on the airdrop data in the table above, from our sample group, **US residents** are estimated to have lost **$1.84 billion to **$2.64 billion in potential revenue** between 2020 and 2024.

According to a report by CoinGecko, which analyzed 50 airdrops (although not a complete list), approximately $26.6 billion was distributed to claimants worldwide via geo-blocked and non-geo-blocked airdrops (the projects it reviewed—see Table 4 in the [Appendix]). [146] Using CoinGecko’s estimate of the total value distributed to claimants via its sample and our calculation of the total number of Americans affected by geo-blocking, **based on CoinGecko’s sample of 21 projects, the total revenue that Americans could lose could be between $3.49 billion and $5.02 billion.**

Estimates of tax losses from airdrop restrictions

Based on an estimate of $1.9 billion in lost airdrop revenue between 2020 and 2024 (our sample), the estimated total revenue lost from airdrops is $2.3 billion.

Joy

Joy