A quick look at Binance Launchpool 63 project Bio Protocol (BIO)

Binance Launchpool has launched the 63rd project - Bio Protocol (BIO), a decentralized science (DeSci) management and liquidity protocol.

JinseFinance

JinseFinance

Compiled by Block unicorn

The precursors to money, along with language, helped early modern humans solve problems of cooperation that other animals cannot, including how to achieve mutual benefit, kin altruism, and reduce aggression. These monetary ancestors had very specific features, just like non-fiat currencies—they were more than just symbolic objects or ornaments.

Currency

When England colonized America in the 17th century, it ran into a problem right from the start—a shortage of metal currency [D94] [T01]. The idea was to use America to grow large quantities of tobacco and provide wood for their global navy and merchant fleets, and then exchange it for the supplies necessary to keep the American land productive. In effect, the early colonists were expected to work for the company and spend money in its stores. Both investors and the British crown wanted this, rather than paying the farmers with metal currency, letting them provide their own supplies, and leaving themselves a little, well, hell-raising profit, as some farmers might have proposed.

There were other ways, and they were right under the colonists' noses, but it took them several years to discover that the natives had their own currency, but it was very different from the currency used by Europeans. American Indians had used currency for thousands of years, and it proved to be very useful to the newly arrived Europeans - except for those who had the prejudice that "only money with the portrait of a big shot was real money." The worst thing was that these New England natives did not use gold or silver. They used the most suitable materials available in their living environment - the long-lasting parts of the bones of prey. Specifically, they used beads (wampum) made from the shells of hard-shelled clams such as venus mercenaria, strung into pendants.

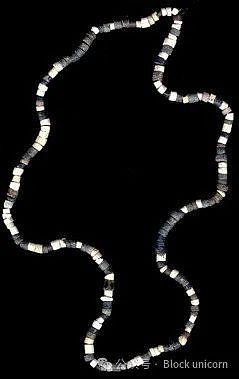

beaded necklaces. During the trade, beads were counted, removed, and strung onto new necklaces. Native American beads were sometimes strung into belts or other commemorative or ceremonial items, indicating wealth or commitment to treaties.

These clams are found only in the ocean, but the beads spread far inland. Various forms of shell money were found in tribes across the continent. The Iroquois, who never ventured into the clams' habitat, collected more bead treasures than any other tribe. Only a few tribes, such as the Narragansett, were proficient in bead making, but hundreds of tribes, mostly hunter-gatherers, used beads as currency. Bead necklaces varied greatly in length, with the number of beads in proportion to the length of the necklace. Necklaces could always be cut or strung together to create lengths that corresponded to the price of the item.

Once the colonists got over their doubts about the source of value for money, they too began buying and selling beads like crazy. Mussels also became another way of saying “money” in American jargon. The Dutch governor of New Amsterdam (now called “New York”) borrowed a large sum of money from the English-American bank—in return, beads. The English authorities were forced to agree, so between 1637 and 1661, beads became legal debt repayment in New England, and colonists had a highly liquid medium of exchange, which helped to boost colonial trade.

But as the English began shipping more metal coins to America and Europeans began using their mass-manufacturing techniques, shell money began to decline. By 1661, the English authorities had conceded defeat and agreed to payment in the kingdom’s metal coins—that is, gold and silver, and that year wampum was outlawed as legal debt repayment in New England.

But in 1710, beads were legal tender in North Carolina, and they continued to be used as a medium of exchange well into the 20th century; but their value increased a hundredfold as Western harvesting and manufacturing techniques evolved, and they followed the path of gold and silver jewelry in the West, from being carefully crafted currency to being ornamental. Shell money has become a strange old word in the American language—after all, "100 shells" has become "100 dollars." "Shelling out" has become paying with metal coins or banknotes, and now with checks or credit cards [D94]. (Translator's note: Shell means shell, that is, "shelling out" originally meant paying with shells.)

We don't realize that this has touched on the origins of our species.

Collectibles

Money in the Americas has taken many forms besides shells. Hair, teeth, and a host of other things were widely used as medium of exchange (their shared properties will be discussed later).

12,000 years ago, the Clovis people in what is now Washington State made some amazing long flint blades. The only problem was that they broke too easily—which meant they were not useful for cutting at all, and the flints were made “for fun,” or for purposes that had nothing to do with cutting.

As we’ll see later, this seeming frivolity was likely to have played an actually important role in their survival.

Native Americans were not the first people to make pretty but useless flint tools, or to invent shell money; nor were Europeans, it should be added, although they also used shells and teeth as currency extensively—not to mention cattle, gold, silver, weapons, and other things. Asians used all of these things, as well as government-issued fake axes, but they also imported the tools (shells). Archaeologists have discovered shell necklaces dating back to the early Paleolithic period—a simple substitute for Native American currency.

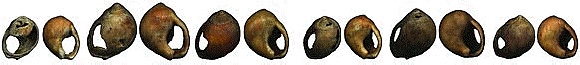

Pea-sized beads made from the shells of the sea snail Nassarius kraussianus. These snails live in estuaries. Found in Blombos Cave, South Africa. Dated to 75,000 years ago.

In the late 1990s, archaeologist Stanley Ambrose discovered necklaces made from ostrich eggshells and shell fragments hidden in a stone shelter in Kenya's Great Rift Valley. Using argon dating (40Ar/42Ar), they dated the necklaces to at least 40,000 years old. Animal tooth beads found in Spain have also been dated to this time. Perforated shells from the Upper Paleolithic have also been found in Lebanon. Recently, intact shells (prepared for beads) were found in Blombos Cave, South Africa, dating back to 75,000 years ago!

Ostrich eggshell beads found in the East African Rift Valley, Kenya. 40,000 years ago. (Thanks Stanley Ambrose)

These modern subspecies of humans migrated to Europe, where shell necklaces and teeth appeared, 40,000 years ago. Shell and tooth necklaces appeared in Australia 30,000 years ago. In all cases, the crafting was highly skilled, suggesting that such practices date back much further than archaeological work has revealed. The origins of collectibles and ornaments are most likely in Africa, where anatomically modern humans originated. There must have been some important survival advantage to collecting and making necklaces, because they were luxurious—they required a great deal of skill and time to make, at a time when humans were often on the brink of starvation.

Virtually all human cultures, even those that did not engage in large-scale trade or use more modern forms of money, made and admired jewelry and objects whose artistic or heritage value outweighed their practical utility. We humans collect shell necklaces and other forms of jewelry—just for pleasure. To evolutionary psychologists, the idea that humans do things for pleasure is not an explanation at all, but simply raises a question. Why do so many people find the sheen of collectibles and jewelry pleasing? More bluntly, the question is—what evolutionary advantage did this pleasure give humans?

A necklace found in a tomb in Sungir, Russia, dating back 28,000 years. It is an interlocking and interchangeable string of beads. Each mammoth ivory bead may have taken an hour or two of labor to make.

Evolution, Cooperation, and Collectibles

Evolutionary psychology stems from a key mathematical discovery by John Maynard Smith. Smith borrowed the population model of co-evolving genes (which came from the well-developed field of Population Genetics) and pointed out that genes can correspond to behavioral strategies, that is, encode good or bad strategies in simple strategic problems (i.e. "games" in the sense of game theory).

Smith showed that competitive situations can be expressed as strategic problems, and that genes must win in the competition to be passed on to subsequent generations, so genes will evolve Nash equilibria of the relevant strategic problems. These competitive games include the prisoner's dilemma (i.e., the archetype of cooperative game problems) and the hawk/dove strategy problem (i.e., the archetype of offensive strategy problems).

The key to Smith's theory is that these strategic games, although seemingly played out over body size, are fundamentally played out between genes - a competition for the spread of genes. It is the genes (not necessarily the individuals) that influence behavior, and appear to have limited rationality (encoding the best possible strategy within the limits of what the organism's body size can express, of course, which is also influenced by the biological raw materials and previous evolutionary history) and "selfishness" (borrowing Richard Dawkins' metaphor). The influence of genes on behavior is an adaptation, an adaptation to the competition that genes carry out through body size. Smith called these evolving Nash equilibria "evolutionarily stable strategies." The "classical theories" that built on earlier theories of individual selection, such as sexual selection and kin selection, were dissolved into this more general model, which subversively placed genes rather than individuals at the center of evolutionary theory. Dawkins thus used an oft-misunderstood analogy—the "selfish gene"—to describe Smith's theory. Few other species are more cooperative than even Paleolithic humans. In some cases, such as incubation and colonization in species such as ants, termites, and bees, animals can cooperate among relatives—because it helps them replicate the "selfish genes" they share with their relatives. In some very extreme cases, non-relatives can also cooperate, which evolutionary psychologists call "mutual altruism." As Dawkins describes it, unless a transaction is a mutual effort, one party can cheat (and sometimes even instant transactions are not immune to fraud). And if they can cheat, they usually do. This is the usual outcome in a game that game theorists call the prisoner's dilemma -- if all parties cooperate, each is better off, but if one party cheats, it can sell out the other suckers and make a profit. In a population of cheaters and suckers, the cheaters always win (making it hard to cooperate). However, some animals cooperate by playing repeated games and using a strategy called tit-for-tat: cooperate in the first round of the game, and then always cooperate until the opponent cheats, then cheat to protect themselves. The threat of retaliation keeps both parties cooperating.

But in general, the situations in which individuals in the animal world actually cooperate are very limited. One of the main limitations of such cooperation is the relationship between the two partners: at least one of them is more or less forced to be close to the other. The most common situation is when parasites and hosts evolve into symbionts. If the interests of the parasite and host are aligned, then symbiosis is more appropriate than separate actions (i.e. the parasite also provides some benefit to the host); then, if they successfully enter a tit-for-tat game, they will evolve into a mutualism, in which their interests, especially the mechanism of gene exit from one generation to the next, are aligned. They will become like a single organism. But in fact, there is not only cooperation between the two, but also exploitation, and it happens at the same time. This situation is very similar to another institution developed by humans - tribute - which we will analyze later.

There are also some very special examples that do not involve parasites and hosts, but still share the same body and become symbionts. These examples involve unrelated animals and very limited territorial space. A beautiful example given by Dawkins is the cleaner fish, which swims in the mouth of the host, eating the bacteria there and maintaining the health of the host fish. The host fish can deceive these fish - it can wait until they have done their job and then swallow them up. But the host fish does not do this. Because both parties are constantly on the move, either party is free to leave the relationship. However, cleaner fish have evolved a very strong sense of territory, as well as stripes and dances that are difficult to imitate - much like a trademark that is difficult to forge. Therefore, the host fish know where to find cleaning services - and they know that if they cheat the fish, they will have to find a new group of fish. The entry cost of this symbiosis is very high (and therefore the exit cost is also high), so both parties can happily cooperate without cheating. In addition, the cleaner fish are very small, so the benefit of eating them is not as good as the cleaning services of a small group of fish.

Another highly related example is the vampire bat. As the name suggests, this bat sucks the blood of mammals. The interesting thing is that whether it can suck blood is very unpredictable. Sometimes you can have a feast, and sometimes you can get nothing. Therefore, the lucky (or more sophisticated) bats will share their prey with the less lucky (clever) bats: the giver will spit out the blood, and the recipient will gratefully eat it.

In most cases, the giver and receiver are related. Of the 110 such cases observed by the extremely patient biologist G.S. Wilkinson, 77 involved mothers nursing their young, and most of the others involved genetic relatives. However, there are still a few cases that cannot be explained by kin altruism. To explain these cases of mutualism, Wilkinson mixed bats from two groups into a single population. He then observed that, with very few exceptions, the bats generally only cared for their old friends from their old group.

This kind of cooperation requires long-term relationships, meaning that the partners interact frequently, know each other, and keep track of each other's behavior. Caves help to confine bats to long-term relationships, so that such cooperation is possible.

We will also learn that some humans have chosen high-risk and unstable harvesting forms like vampire bats, and they also share the surplus of their production activities with unrelated people. In fact, they have achieved this achievement far more than vampire bats, and how they achieve this achievement is the subject of this article. Dawkins says that “money is a formal token of delayed reciprocal altruism,” but then he stops short of pushing this fascinating idea. That is the task of this article.

In small human groups, public reputation can replace retaliation from individual individuals, motivating people to cooperate with delayed exchange. However, reputation systems can suffer from two major problems—difficulties in identifying who did what, and difficulties in assessing the value or damage caused by actions.

Remembering faces and corresponding favors is a nontrivial cognitive hurdle, but one that most humans find relatively easy to overcome. Recognizing a face is easy, but remembering that a favor occurred when needed can be harder. Remembering the details of a favor that brought some value to the recipient is even harder. Avoiding arguments and misunderstandings can be impossible, or so difficult that such help cannot occur.

The valuation problem, or the problem of measuring value, is very broad. For humans, it exists in any system of exchange—whether it is favors, barter, money, credit, employment, or market transactions. This question is important in extortion, taxation, tribute, and even judicial punishment. It is even more important in reciprocal altruism among animals. Imagine a monkey doing a favor—say, exchanging a piece of fruit for a back scratch. Grooming each other removes lice and fleas that can’t be seen or scratched. But how many groomings for how many pieces of fruit does it take for both parties to feel it’s “fair” and not a rip-off? Is a 20-minute grooming service worth one or two pieces of fruit? How big a piece?

Even the simplest “blood for blood” trade is more complicated than it seems. How does a bat estimate the value of the blood it receives? Based on weight, volume, taste, satiety, or other factors? This measurement complexity is exactly the same in the monkey’s “you scratch my back, I’ll scratch yours” trade.

Despite the many potential trade opportunities, animals have trouble figuring out how to measure value. Even in the simplest model of remembering faces and matching them to a history of favors, getting all parties to agree on the value of favors with enough precision in the first place is a major obstacle to the development of reciprocity.

But even the stone toolkits left by Paleolithic humans seem a bit too complex for our brains.Tracking the favors associated with these stones—who made what quality tools, for whom, who owed what, and so on—would be very complicated across tribal boundaries. In addition, there may be a large number of organic objects and temporary services (such as grooming) that have not survived. Even if only a small number of these traded goods and services are kept in mind, as the number of them increases, it will become increasingly difficult or even impossible to match people with things. If cooperation did occur between tribes, as the archaeological record suggests, the problem becomes more difficult, because hunter-gatherer tribes are often highly hostile and distrustful of one another.

If shells can be money, furs can be money, gold can be money, and so on—if money is not just coins and notes issued by governments under legal tender laws, but can be many different things—then what is the nature of money?

And why would humans, often on the brink of starvation, spend so much time making and admiring necklaces when they could be hunting and gathering?

The 19th-century economist Carl Menger first described how money evolved naturally, emerging inexorably from a vast array of barter transactions. The story told by modern economics is something like Menger’s version.

Barter requires a coincidence of interests on both sides of the transaction. Alice grows some walnuts and needs some apples; Bob happens to grow apples and wants walnuts. And they happen to live close together, and Alice trusts Bob to wait quietly between the walnut harvest and the apple harvest. Assuming all these conditions are met, bartering is fine. But if Alice grows oranges, even if Bob wants oranges, that's out of the question - oranges and apples don't grow in the same climate. If Alice and Bob don't trust each other and can't find a third party to mediate or enforce the contract, then their wishes will be in vain.

There are even more complicated situations. Alice and Bob can't fully honor their promise to sell walnuts or apples in the future because, as an alternative, Alice could keep the best walnuts for herself and sell the inferior ones to the other party (and Bob could do the same). Comparing quality, comparing the quality of two different things, is even more difficult than the above problems, especially when one of the things is a memory. Also, neither of them can predict events such as a bad harvest. These complications greatly complicate the problem Alice and Bob are dealing with, making it harder for them to confirm that a delayed reciprocal exchange is actually reciprocal. The longer the time between the initial and return transactions, and the greater the uncertainty, the greater the complexity. A related problem (which engineers might recognize) is that barter “doesn’t scale.” Barter works when there are small quantities of goods, but it becomes increasingly expensive as the quantity increases, until it becomes too expensive to do the exchange. Suppose there are N goods and services, so a barter market would have N2 prices. Five goods would have 25 relative prices, which is fine; but 500 goods would have 250,000 prices, far more than one person can realistically keep track of. With money, however, there are only N prices — 500 prices for 500 goods. When used in this context, money acts as both a medium of exchange and a standard of value—as long as the price of the money itself is not too large to be remembered or changes too frequently. (The latter problem, along with the implicit insurance "contract" and the lack of competitive markets, may explain why prices are usually evolved over the long term rather than determined by near-term negotiations.)

In other words, barter requires a coincidence of supplies (or skills), preferences, time, and low transaction costs.Transaction costs in this model can grow much faster than the variety of goods. Barter is certainly better than no trade at all, and it has been widespread. But it is still quite limited compared to trade with money.

Primitive money existed long before large-scale trade networks emerged.Money had an even more important purpose before that. By greatly reducing the need for credit, money greatly improved the efficiency of small barter networks.A perfect coincidence of preferences is much less than a coincidence of preferences across time. With money, Alice can gather blueberries for Bob this month, and Bob can hunt for Alice six months from now when the big game migrates, without having to keep track of who owes whom what, and without having to trust each other's memory and integrity. A mother's significant investment in raising a child can be protected by the gift of an unforgeable object of value. And money transforms the division of labor problem from a prisoner's dilemma to a simple exchange.

The primitive money used by hunter-gatherers is very different in appearance from modern money and plays a different role in modern culture; primitive money may have some functions that are limited to small exchange networks and local institutions (as we will discuss later). For this reason, I think it is more appropriate to call them "collectibles" rather than "currency." In the anthropological literature, such objects are also called "currency"; this definition is broader than government-issued paper money and metal currency, but narrower than "collectibles" or the more vague "valuable objects" that we will use in this article (valuable objects will be used to refer to things that are not collectibles in this sense).

The reasons for choosing "collectibles" rather than other terms to refer to primitive money will become apparent later. Collectibles have very specific properties and are not simply decorative. While the specific objects and valuable properties of collectibles vary from culture to culture, they are by no means arbitrary. The primary function of collectibles, and their ultimate function in evolution, is to serve as a medium for storing and transferring wealth. Some types of collectibles, such as necklaces, are well suited to use as money, and even we (who live in a modern society where economic and social conditions encourage trade) can understand them. I will also occasionally use "primitive money" instead of "collectibles" to discuss wealth transfer before the age of metal money.

Gains from Trade

Individuals, clans, and tribes voluntarily engage in trade because both sides of the trade believe they have gained something. Their value judgments may change after the trade, for example, because they have gained experience with the goods and services that have been traded (thus changing their criteria). However, at the time of the transaction, their value judgments may not be exactly commensurate with the value of the items traded, but they are generally correct in their judgment of whether the transaction is beneficial. Especially in early intertribal trade, where trade was limited to high-value items, all parties had strong incentives to make their judgments accurate. As a result, trade almost always benefited all parties. Trade activities were no less valuable than physical activities such as manufacturing.

Because individuals, clans, and tribes had different preferences, different abilities to satisfy those preferences, and different perceptions of their own skills and preferences and their results, they always had something to gain from trade. Whether the costs of conducting the trade itself—the transaction costs—were low enough to make it worthwhile is another question. In our own time, there is far more trade that can take place than in most previous times. However, as we will see below, some types of trade have always been worth the transaction costs, and for some cultures, such trade can be traced back to the early days of homo sapiens sapiens.

It is not only voluntary spot transactions that benefit from lower transaction costs. This is crucial to understanding the origin and evolution of money. Family heirlooms could be used as collateral, eliminating the credit risk of delayed exchange. The ability to collect tribute from defeated tribes was a great boon to the victorious tribe, and this ability benefited from the same transaction cost technologies as trade; arbitrators assessing actual damages for violations of custom and law, and even kin groups arranging marriages. Kin also benefited from timely and peaceful gifts of wealth by inheritance. The major activities of human life in modern culture, isolated from the world of commerce, benefited as much as, or more than, technologies that reduced transaction costs, and none of these technologies was more efficient, more important, or appeared earlier than the original money - collectibles.

After Homo sapiens replaced H. sapiens neanderthalis, human numbers subsequently exploded. Artifacts found in Europe, dating from 35,000 to 40,000 years ago, show that Homo sapiens increased the carrying capacity of the environment by a factor of 10—that is, by a factor of 10—than the Neanderthals. Not only that, but the newcomers had time to create some of the world’s earliest art—beautiful cave paintings, a variety of exquisite sculptures—and, of course, necklaces made of shells, teeth, and eggshells.

These objects were not useless decoration. New and efficient ways of transferring wealth were enabled by these collectibles and perhaps by higher levels of progress and language; the new cultural tools thus created may have played a major role in increasing the carrying capacity of the environment.

As newcomers, Homo sapiens had brains comparable to those of Neanderthals, softer bones, and less muscular muscles. Their hunting tools were more sophisticated, but by 35,000 years ago, they were basically the same—not even twice as efficient, let alone 10 times as efficient. The biggest difference may be the wealth transfer tools that collectibles create and even improve. Homo sapiens derive pleasure from collecting shells and using them to make jewelry, display jewelry, and trade with each other. Neanderthals did not. Perhaps it is because of this same mechanism that Homo sapiens survived the vortex of human evolution and emerged on the Serengeti plains of Africa tens of thousands of years ago.

We should talk about how collectibles reduce transaction costs by type - from voluntary free bequests, to voluntary mutual trade and marriage, to involuntary judicial decisions and tribute.

All types of value transfer have occurred in many prehistoric cultures, probably dating back to the beginnings of Homo sapiens. The benefits to one or more parties from the transfer of wealth in major life events are so great that they can ignore the high transaction costs. Compared with modern money, the circulation rate of primitive money is very low - it may change hands only a few times in the life of an average person. However, a collectible that can be preserved for a long time, what we would call an "heirloom" today, can remain intact for generations and increase in value with each change of hands - often enabling transactions that would not otherwise occur. Tribes therefore spend a lot of time on seemingly meaningless manufacturing work and exploring new materials for use.

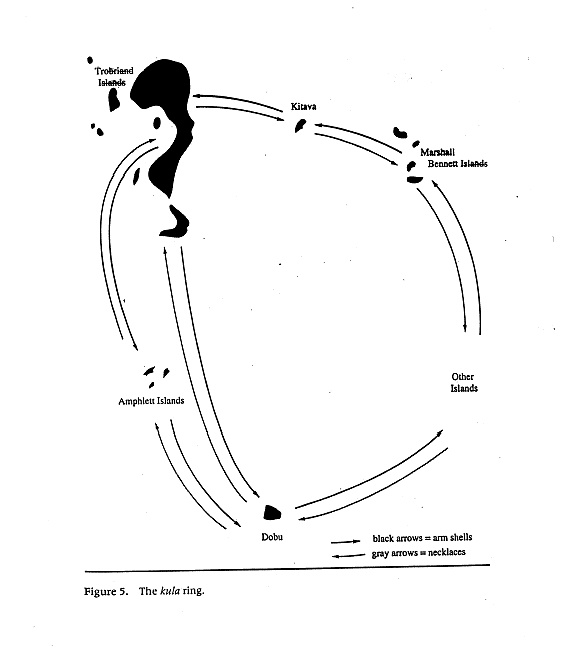

Kula Circle

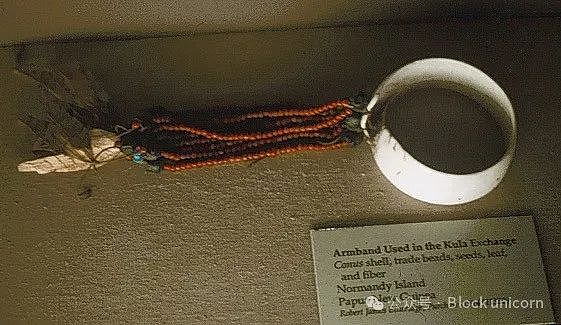

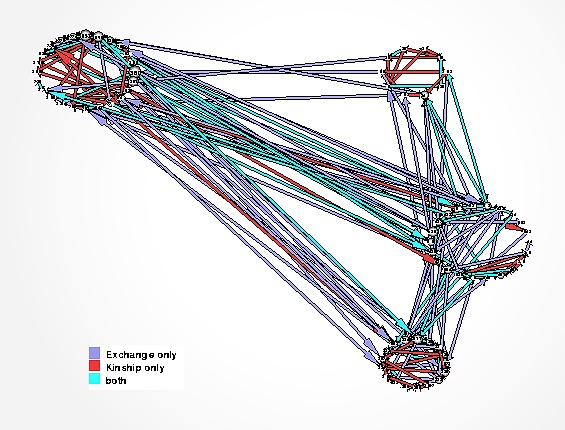

Kula trade network on the Melanesian Islands in pre-colonial times. Kula is both a "very strong" currency and a monument to stories and legends. The goods that can be traded (mostly agricultural products) are distributed in different seasons, so barter is not feasible. Kula collectibles have precious value that cannot be forged, and they can be worn and circulated; as a currency, it solves the double coincidence of needs. Because this problem can be solved, a bracelet or necklace can be worth more than its production cost after just a few trades and can continue to circulate for decades. Legends and stories about the previous owner of the collectible further provide information about upstream credit and liquidity. In Neolithic cultures, the shapes of the collectibles (usually shells) in circulation tend to be more irregular, but the purpose and attributes are similar.

Mwali bracelet

Bagi necklace

For any tool whose main function is to transfer wealth, we can ask the following question:

Do the two events (i.e., the production and use of the traded item) have to meet a certain coincidence in time interval? How much of an obstacle does the impossibility of coincidence bring to wealth transfer?

Can the transfer of wealth form a collectible cycle based on this tool alone, or do other tools need to complete the cycle? A careful study of the actual picture of money circulation is crucial to understanding the birth of money. For most of human prehistory, money circulation covering a large number of different transactions did not exist and could not exist. Without a complete and repeated cycle, collectibles cannot circulate and become worthless. A collectible must be able to mediate enough transactions to amortize its production costs, so that it is worth making.

Let's first study the most familiar and economically important type of wealth transfer today - trade.

Starvation Insurance

Bruce Winterhalder observed occasional patterns of food transfer between animals: tolerated theft, production/begging/opportunism, risk-sensitive survival conditions, reciprocity as a byproduct, ex post facto rewards, non-spot exchanges, and other patterns (including kin altruism). Here we focus only on risk-sensitive survival, delayed reciprocity, and non-spot transactions. We argue that food sharing can be increased by replacing delayed reciprocity with food-collectibles exchanges. Doing so reduces the risk of variable food supplies while avoiding most of the problems that delayed reciprocity between bands cannot overcome. We will later treat kin altruism and the problem of theft (with or without forgiveness) in a larger context.

Food is more valuable to the hungry than to the well-fed. If a starving and desperate person can use his most valuable possession to save his life, then the months of labor spent on that treasure are worth it. People often value their own lives more than that heirloom. Collectibles, then, are like fat, providing insurance against food shortages. Famine caused by local food shortages can be remedied in at least two ways - the food itself, and the right to forage and hunt.

However, transaction costs are generally too high - war rather than trust between groups is more common. Groups that cannot find food often starve. But if transaction costs can be reduced by reducing the need for mutual trust between groups, food that is worth only one day's labor for one group may be worth several months' labor for a hungry tribe (and they can trade with each other).

As this article shows, the most valuable trade that can be achieved on a small scale emerged in many cultures during the Upper Paleolithic with the emergence of collectibles. Collectibles replace long-term trust relationships that would otherwise have to exist (but do not actually exist). If long-term interactions and trust already existed between tribes or between individuals from different tribes, the extension of credit between them without collateral would greatly stimulate intertemporal barter. However, such high levels of mutual trust are unthinkable - just because of the problems with the reciprocal altruism model mentioned above, and these theories are confirmed by empirical evidence: most of the hunter-gatherer tribes we observe have very tense relations. For most of the year, hunter-gatherer tribes are scattered in small groups, occasionally gathering in "aggregates" like medieval fairs for only a few weeks a year. Although there was no trust between groups, a significant trade in products, such as the type shown in the accompanying figure, almost certainly occurred in Europe and almost everywhere else, such as among big-game hunting tribes in the Americas and Africa.

This scenario is entirely theoretical, but it would be surprising if it were not true. Although many European Paleolithic peoples favored shell necklaces, many people living further inland used their teeth rather than shells to make necklaces. Flint, axes, furs, and other collectibles were also likely used as a medium of exchange.

Reindeer, bison, and other game migrated at different times of the year. Different tribes specialized in different prey, and more than 90% or even 99% of the remains from the European Paleolithic were from the same species. This scenario suggests at least a seasonal division of labor within a tribe, or even complete division of labor within a tribe for each type of prey. To achieve this level of division of labor, members of individual tribes had to become specialists in the behavior, migration, and other patterns of that species, in addition to the specialized tools and techniques used to kill it. Some tribes we have observed in modern times had division of labor. Some North American Indian tribes specialized in hunting bison and antelope, as well as salmon. In parts of northern Russia and Finland, many tribes, including the Lapps, herd only one species of reindeer even to this day.

The large wild animals that were not afraid of humans no longer existed. In the Paleolithic period, they were either driven to extinction or learned to fear humans and their projectile weapons (in this case, bows and arrows). However, for most of the time of Homo sapiens, wild animal populations were plentiful and easily captured by professional hunters. According to our trade-subsistence theory, it is very likely that specialization was higher during the Paleolithic, when many large game animals (horses, bison, large elk, reindeer, large sloths, mastadons, mammoths, zebras, elephants, hippos, giraffes, musk oxen, etc.) roamed in large groups across North America, Europe, and Africa. This division of labor among tribes is also consistent with (though not reliably proven) archaeological evidence from the Paleolithic in Europe.

These migratory groups, following their prey, often interacted with each other, creating many opportunities for trade. American Indians preserved food by drying and making pemmican, which lasted for several months but not generally for a whole year. This food was exchanged for hides, weapons, and collectibles. These trades usually took place in annual trade events.

The large migratory herds passed through a territory only twice a year, often with a one- to two-month interval; without other sources of protein, these specialized tribes would have starved. Only trade could have made possible the high degree of specialization reflected in the archaeological evidence. Thus, even if only seasonal meat could be exchanged, collectibles would have been worth using.

Those necklaces, flints, and other currency items circulated back and forth in a closed loop, and as long as roughly equal amounts of meat were traded, roughly equal amounts of collectibles were traded. Note that, assuming that the theory of collectible circulation constructed in this article is correct, it is not enough to have only one-way beneficial trade. We must identify closed cycles of two-way beneficial trade in which collectibles continue to circulate and spread their production costs.

As mentioned above, we know from the archaeological evidence that many tribes specialized in hunting a single species of large game. That is, hunters at least hunted different animals seasonally (seasonal division of labor within the tribe); if there was extensive trade, it was also possible that a tribe hunted only one type of game throughout the year (complete division of labor between tribes). Although a tribe could gain huge production benefits by becoming an expert on the habits of animals and the best hunting methods, this benefit would not be achieved if it had to go through much of the year without catching anything.

If trade was limited to two complementary tribes, the total food supply might be roughly doubled. However, in the Serengeti and the European steppes, more than a dozen species of animals would often pass through instead of just two. Thus, for a specialized tribe, the available meat would be more than doubled by trade. More importantly, the extra meat would be there when people needed it.

Thus, even the simplest cycle of two prey species and two different but compensating exchanges can provide at least four benefits (or sources of “surplus”) to the participants:

Eat meat during otherwise starving seasons;

Increase in the total supply of meat—they can sell meat they can’t eat right now or save, since it would otherwise go to waste;

Increase in nutritional diversity by having different meats to eat;

Higher productivity due to specialization in hunting activities.

Making or keeping collections to exchange for food is not the only insurance against starving seasons. Perhaps more common (especially in areas where large game hunting is not possible) is the transferable hunting rights over territory. This can be observed in many of the surviving hunter-gatherer cultures today.

The !Kung San of southern Africa, like all surviving hunter-gatherer cultures today, lived on the margins. They had no opportunity to become professional hunters, and had to make do with the meager resources they had. Perhaps this made them less like ancient hunter-gatherers, and less like primitive Homo sapiens (the people who seized the most fertile land and the best hunting routes from the Neanderthals and only later pushed them out of the margins entirely). But despite their harsh natural environment, the !Kung also used collectibles for trade.

Like most hunter-gatherer cultures, the !Kung lived in small, scattered groups for much of the year, gathering only for a few weeks with a few other groups. Gatherings were like markets with additional functions—to facilitate trade, to solidify alliances, to strengthen partnerships, to buy and sell in-laws. Preparing for a gathering involved making tradeable objects, some of which were practical, but most of which were collectible. This trading system, called !Kung hxaro, involved the trade of large amounts of hanging jewelry, including ostrich eggshell necklaces; and these collectibles are very similar to what was found in Africa 40,000 years ago.

Patterns and kinship in the hxaro trading system between neighboring tribes of the !Kung

Necklaces used in haxro trading

One of the items that the !Kung bought and sold with collectibles was the abstract right to enter the territory of other groups (and gather and hunt). This trade was particularly active when local food was scarce, because foraging in a neighbor's territory could alleviate hunger. The !Kung used arrows to mark the group's territory; trespassing without purchasing the right to enter and forage was akin to declaring war. Like intergroup food trade, buying foraging rights with collectibles was also a form of "insurance against starvation" (to borrow Stanley Ambrose's phrase).

Although anatomically modern humans can think consciously, speak, and have some planning abilities,trading requires little in the way of advanced thinking and language, and even less planning abilities. For tribesmen did not need to infer benefits beyond trade. To produce such tools, people simply followed an instinct to seek objects with certain properties (as we saw in the indirect observation of accurate assessments of those properties). This also applies to varying degrees to the other institutions we will learn about—they evolved rather than being consciously designed. No one involved in this explains the role of these institutions in terms of evolutionary function; instead, they explain these behaviors with many different myths, and the myths are more like direct incentives for these behaviors than theories about their origins and ultimate purposes.

Direct evidence for food trade has long been lost to history, and we may find more direct evidence in the future than we do now, by comparing the hunting patterns of one tribe with the consumption patterns of another tribe among existing hunter-gatherer tribes - the hardest part may be to identify the boundaries of different tribes or kin groups. According to our theory, such inter-tribal meat exchange should have been widespread across most of the Paleolithic, when large-scale specialized hunting emerged.

Now, we have additional indirect evidence, which is the transfer of collectibles themselves. Fortunately, the long-term survival properties required for objects to become collectibles are the same properties that allow artifacts to survive and be found by archaeologists.

The mainstream of inter-tribal relations is mutual distrust when good, and violence when bad. Only ties of marriage or kinship allowed tribes to trust each other, albeit only occasionally and on a limited scale. Although collectibles could be worn or hidden in carefully concealed cellars, the tenuous ability to protect property meant that the cost of making them had to be amortized over a few transactions. Trade, therefore, must not have been the only form of wealth transfer, and it was probably not even the main one during humanity’s long prehistory, when transaction costs would have made it impossible to develop markets, corporations, and other economic institutions we take for granted today. Beneath our great economic system, there were older ones that also involved wealth transfer. All of these institutions distinguished Homo sapiens from all other animals. We now turn to the most basic form of wealth transfer—one that humans take for granted but animals seem to lack—inheritance.

The coincidences of supply and demand in time and place were so rare that most of the types of trade and trade-based economic institutions we take for granted today could not have existed. Even less likely is the triple coincidence of events that would satisfy the needs of provisioning and kinship groups (such as the founding of a new family, death, crime, victory or defeat). So we see that both clans and individuals benefited greatly from the timely transfer of wealth at these events. Moreover, such wealth transfers were less wasteful because they involved the transfer of value only in long-lasting stores of wealth, not in consumer goods or tools for other purposes. The need for durable and universal stores of wealth in these institutions was often more pressing than the need for a medium of exchange in trade. Furthermore, marriage selection, inheritance, dispute mediation, and tribute probably predate intertribal trade and involve more wealth transfers than trade does. Thus, these institutions are more powerful drivers of the emergence of primitive money than trade.

In most hunter-gatherer tribes, wealth transfers took forms that would strike us modern “rich” as trivial: a set of wooden utensils, flint and bone tools, weapons, shell necklaces, even a hat, or in colder climates, perhaps some moss-covered fur. Sometimes all of these things were things you could wear. These various things were hunter-gatherer wealth, just as real estate, stocks, and bonds are to us. Tools and warm clothing were essential for survival. Many of the items in wealth transfer were valuable collectibles that could be used to stave off starvation, buy mates, and save lives in war and defeat.

The ability to transfer survival capital to future generations was another advantage Homo sapiens had over other animals. Further, skilled tribesmen or clans could trade excess consumer goods for durable wealth (especially collectibles) only occasionally, but they could accumulate over a lifetime. A temporary adaptive advantage was thus transformed into a permanent adaptive advantage for future generations.

Another form of wealth (also not excavated by archaeologists) was official position. In many hunter-gatherer tribes, social status was more valuable than tangible wealth. Such positions included tribal chieftains, military leaders, hunting party leaders, members of long-term trading partnerships (with other tribes), midwives, and religious leaders. Collectibles were often not only a symbol of wealth, but also a symbol of tribal responsibility and status. When a person of status died, his replacement had to be appointed quickly and clearly in order to maintain order. Delays could breed hostility. Funerals were therefore public events in which the deceased was honored and his wealth, both tangible and intangible, was divided among his descendants, as determined by tradition, tribal decision-makers, and the will of the deceased.

As Marcel Mauss and other anthropologists have pointed out, other than inheritances, free gifts of other kinds were rare in pre-modern cultures. What seemed like free gifts actually implied obligations on the recipient. Before the advent of contract law, this implicit obligation of "gift," and the group condemnation and punishment that followed when someone refused to obey it, was probably the most common motivation for delayed transactions to go back and forth, and it remains common today when we provide informal support to each other. Inheritance and other forms of kin altruism are the only forms of gifts that have been widely practiced, according to our modern definition of "gift" (i.e., gifts that do not impose obligations on the recipient).

Early Western merchants and missionaries often viewed indigenous peoples as underdeveloped races, sometimes referring to their tribute trade as "gifts" and trade as "gift trading," believing that these behaviors were more like the Christmas and birthday gift exchanges of Western children than legal and tax obligations between adults. This view is partly prejudice, but it also reflects the fact that legal obligations in the West at that time were written down, while the locals did not have legal documents. Therefore, Westerners often translated the words that indigenous peoples used to describe trading systems, rights, and obligations into "gifts." In the 17th century, French colonists in America were scattered around several more populous Indian tribes, and they often had to pay tribute to these tribes. Calling these tributes "gifts" was a way for them to save face with Europeans, because other Europeans did not feel the need to pay tribute and would regard paying tribute as cowardice.

Unfortunately, both Mauss and modern anthropologists have retained the term. These savages are still childlike, childlike, and morally superior to our cold-blooded economic transactions. However, in the West, and especially in the formal language of the laws governing transactions, a "gift" refers to an exchange without any obligations attached. These things should be kept in mind when we encounter anthropological discussions of "gift exchange" - anthropologists do not refer to free or informal gifts in the sense that we think of them in everyday life. They refer to the very complex system of rights and obligations involved in the transfer of wealth. The only forms of exchange in prehistoric cultures that resemble modern gifts, in which the gift itself is neither a widely recognized obligation nor intended to impose any obligations on the recipient, are the care of children given by parents or maternal relatives, and inheritance. (The exception is the inheritance of a title, which imposes the responsibilities and privileges of the position on the heir).

Some heirlooms may be broken over generations, but they do not in themselves form a closed loop of collectible transfer. Heirlooms are valuable only if they can eventually be used for something else. They are often traded between clans and in-laws, thus forming a closed loop of collectibles.

Family Trade

The early important examples of small closed-loop networks of collectibles involved the higher investment in raising offspring (compared to our primate relatives) made by humans and the related human institution of marriage.

Marriage, a mixture of long-term matching for mating and raising, inter-tribal negotiations, and wealth transfer arrangements, is a universal human phenomenon, probably as old as Homo sapiens.

The investment in parenthood is long-term, but it is almost a one-time deal - there is no time for re-selection. From the perspective of genetic fitness, divorcing a philandering husband or unfaithful wife usually means wasting several years of your life with the unfaithful one. Fidelity and commitment to children is primarily guaranteed by in-laws (that is, clans). Marriage was essentially a contract between clans, often involving such fidelity and commitment, as well as a transfer of wealth.

Men and women rarely contributed equally to a marriage, especially in an era when the clan was in charge of marriage and there were few good choices for clan leaders. Most often, women were considered more valuable, so the groom's clan paid a fee to the bride's clan. By contrast, it was rare for the bride's family to pay the groom's clan. This was generally practiced only by the upper classes in monogamous, highly unequal societies (such as medieval Europe and India), and was ultimately fueled by the huge potential advantages of upper-class men over women. Because most of the literature was written about the upper classes, dowries often have a place in European traditional stories. This does not reflect its universality in human culture - in fact, dowries are rare.

Inter-clan marriages can form closed loops of collectibles. In fact, two clans that exchange members can form a closed loop as long as the brides wish to exchange collectibles. If a family is richer in collectibles, they can get better brides for their sons (in monogamous societies) or more brides (in polygamous societies). In a cycle involving only marriage, primitive money can replace the family's need for memory and trust, allowing renewable resources to be paid on credit and over long periods of time.

Like inheritance, litigation, and tribute, marriage requires a triple coincidence of events. Without a transferable and durable store of value, the ability of the groom's family to satisfy the bride's wishes is unlikely to be satisfactory (this ability also largely determines the value mismatch between bride and groom, of course, and marriage also satisfies the political and romantic needs of matching). One solution is to impose a long-term and ongoing service obligation on the groom and his family to the bride's family. This solution occurs in 15% of known cultures. In 67% of the cases, the groom or his family pays a large sum of wealth to the bride's family. Sometimes bride prices are paid in ready-made consumer goods, that is, plants gathered or harvested for the wedding and animals killed for the wedding. In pastoral or agricultural societies, most bride prices are paid in livestock (which is also a form of wealth that can last for a long time). The remainder - and usually the most valuable part of the bride price in cultures without livestock - is usually paid in the most valuable heirlooms: the rarest, most luxurious, and most durable necklaces, rings, and so on. In the West, the groom giving the bride a ring (and the suitor giving the woman other forms of jewelry) was once a large transfer of wealth, and it is also common in many other cultures. In about 23% of cultures (mostly modern cultures), there is no large transfer of wealth. 6% of cultures have wealth transfers between men and women. In only 2% of cultures does the bride's family provide a dowry to the new couple.

Unfortunately, some wealth transfers are far from altruistic and marital good, such as tribute.

War Spoils

In chimpanzee communities and even hunter-gatherer cultures (and their cousins), rates of death from violence are far higher than in modern civilizations. This goes back at least to our common ancestor with chimpanzees, where groups of chimpanzees have always been at odds with each other.

Warfare involves killing, maiming, torture, kidnapping, rape, and the extortion of tribute as a threat of such a fate.

When two neighboring tribes are at peace, one usually pays tribute to the other. Tribute can also be used to forge alliances and achieve economies of scale in war. Most of the time, this is a form of exploitation that brings greater benefits to the victor than inflicting further violence.

Victory in war is usually followed by an immediate transfer of value from the loser to the winner. In form, this transfer usually takes the form of plunder by the victor and desperate hiding by the loser. More often, the vanquished paid tribute to the victors at regular intervals. Here again, the triple coincidence problem arises. Sometimes, this problem can be avoided by complex ways of reconciling the vanquished’s ability to supply with the victor’s needs. But even so, primitive money provided a superior solution—a recognized medium of value greatly simplified the terms of payment—which was important in an age when terms could not be written down or remembered. In some cases, such as the shells of the Iriquois Confederacy, collectibles also served as primitive souvenirs that, while not as precise as written text, could be used to help recall the terms. For the victors, collectibles provided a way to collect tribute as close to Laffer’s optimal tax rate as possible. For losers, because collectibles can be hidden, they can "underreport their wealth," causing winners to collect less tribute because they don't have as much wealth. Hidden collectibles also provide a kind of insurance against greedy looters. Because of this hidden nature, much of the wealth of primitive societies has escaped the attention of missionaries and anthropologists. Only archaeologists can unearth this hidden wealth. Hiding collectibles and other strategies present collectible looters with the same problem that modern tax collectors face: how to estimate the wealth they can extract. While measuring value is a problem in many types of transactions, none is more difficult than in hostile taxation and tribute. By making difficult and unintuitive trade-offs, coupled with a series of visits, audits, and collections, tribute payers eventually maximize their benefits, even if the result is very expensive for the tribute payer.

Suppose a tribe wants to collect tribute from several defeated tribes. They must estimate how much value they can extract from each tribe. Faulty estimates can allow some tribes to hide their wealth while over-exploiting others, causing the lost tribes to shrink and the benefited tribes to pay relatively less tribute. In all these cases, the victors are likely to gain more by using better rules. This is the role of the Laffer curve in guiding tribal wealth.

The Laffer curve was proposed by the outstanding economist Arthur Laffer to analyze tax revenue problems: as tax rates increase, tax revenue will rise, but it will rise more and more slowly because there will be more tax evasion and, most importantly, people will be disincentivized to participate in the taxed activities. For these reasons, there is a tax rate that maximizes tax revenue. Raising the tax rate above the Laffer optimal tax rate will actually reduce government revenue. Ironically, the Laffer curve is often used to argue for low tax rates, although it is itself a theory about maximizing government tax revenue, not a tax theory about maximizing social welfare or maximizing individual satisfaction.

Over the long term, the Laffer curve is perhaps the most important economic principle in political history. Charles Adams used it to explain the rise and fall of dynasties. The most successful governments are guided by their own interests to maximize their revenues according to the Laffer curve—both in the short term and in the long term success of other governments. Governments that tax too much, such as the Soviet Union and the later Roman Empire, eventually disappear into history; governments that tax too little are often conquered by better-financed neighbors. Historically, democratic governments have often been able to maintain high tax revenues by peaceful means, without waging war; they are the first countries in history to have tax revenues so high relative to foreign enemies that they can spend much of the money on nonmilitary matters; and their tax systems are closer to the Laffer optimal rate than most previous types of governments. (Another view is that this leisure to spend money was created by the deterrent power of nuclear weapons, rather than by the increasing desire of democratic governments to maximize tax revenue.)

When we apply the Laffer curve to examine the relative effects of tribute contracts on different tribes, we can conclude that the desire to maximize revenue leads victors to want to accurately calculate the income and wealth of conquered tribes. The way in which value is measured crucially determines how tribute payers can evade the burden of tribute by hiding their wealth, fighting, or fleeing; tribute payers have many ways to cheat these estimates, such as hiding collectibles in cellars. The collection of tribute is a game of misaligned incentives around value estimates.

With collectibles, victors can demand tribute from tribute payers at the (strategically) most appropriate time, rather than accommodating the time when the tribute payers can provide or the time when the victor needs it. With collectibles, victors are also free to choose when to consume the wealth, rather than being forced to consume it at the same time as receiving the tribute.

By 700 BC, trade was common, and money was still in the form of collectibles - although it was made of precious metals, its basic characteristics (lack of a common value scale) were very similar to most primitive money since the beginning of Homo sapiens. This situation was changed by the Greek-speaking Lydians who lived in Anatolia (now Turkey). Lydian kings were the first issuers of metal coins in the archaeological and historical record.

From then until now, governments have given themselves monopolies to mint coins, rather than private minting. Why not let private enterprises (such as private banks, which are always absent in these quasi-market economies) control the minting of coins? The main reason people put forward is that only governments can enforce anti-counterfeiting measures. However, they can enforce such measures to protect competing private minters, just as you can prohibit the counterfeiting of trademarks and use the trademark system.

It is much easier to estimate the value of metal coins than to estimate the value of collectibles - transaction costs are much lower. With money, much more trade could be done than with barter alone; indeed, many types of low-value transactions became possible because, for the first time, the small gains from these transactions were greater than the associated transaction costs. Collectibles were low-velocity money that participated in only a few high-value transactions; metal money, with its higher velocity, facilitated a large number of low-value transactions. Given the benefits we have seen from primitive money for tribute systems and tax collectors, and the inevitable value estimation problems involved in optimizing compulsory payments, it is not surprising that tax collectors (especially the Lydian kings) became the first issuers of metal money. The king, whose revenue came from taxes, had a strong incentive to estimate more accurately the wealth held and exchanged by his subjects. On the other hand, market transactions also benefited from cheaper means of measuring value, creating institutions that approached efficient markets and, for the first time in history, individuals could participate in large-scale markets; these were unintended side effects of the king's plan. The greater wealth that came with markets also became taxable items, and the king's revenue from this exceeded even the Laffer curve effect of reducing measurement errors given the resources for the tax. In other words, more efficient taxation, coupled with more efficient markets, results in a significant increase in overall tax revenue. These tax collectors were like gold mines, and the Lydian kings Midas, Croesus, and Giges are famously wealthy to this day.

Centuries later, the Greek king Alexander the Great, who conquered Egypt, Persia, and much of India, financed his expeditions by looting Egyptian and Persian temples,specifically, by taking the low-volatility collectibles hidden in the temples and minting them into high-volatility coins. He thereby conjured up an efficient economy and a more efficient tax system.

Tribute by itself does not form a collectibles loop. Tribute is valuable only if the victor can trade it for something else, such as marriage, trade, or collateral. However, the victor can force the vanquished into manufacturing to obtain collectibles, even if it does not actively want to do so.

Disputes and Compensation

Ancient hunter-gatherer tribes did not have modern tort or criminal laws, but they had a similar method of reconciling disputes, using clan or tribal leaders or voting to make judgments, covering the range of what modern law calls crimes and torts. Resolving disputes through penalties or fines prevented the disputing clans from falling into a cycle of murder. Many pre-modern cultures, from the Iroquois in the United States to the pre-Christian Germans, believed that compensation was better than punishment. All achievable torts, from petty theft to rape to murder, had a price (such as the German "weregeld" and the Iroquois blood money). Where money was available, compensation was paid in money. Livestock was also used in pastoral cultures. Otherwise, collectibles were most common.

Compensation for damages in lawsuits or similar complaints again leads us to the triple coincidence of events, supply, and need, just as in the problems of inheritance, marriage, and tribute. Without a solution, the verdict must compromise the defendant's ability to pay compensation and the plaintiff's opportunity and desire to benefit from it. If the compensation is a consumer good that the plaintiff already has in large quantities, then although these compensations constitute a punishment, they may not satisfy the plaintiff - and therefore fail to stop the cycle of violence. Here again, we can use collectibles to solve the problem - so that compensation always resolves disputes and ends the cycle of revenge.

If compensation payments can completely eliminate grudges, then they cannot form a closed loop. However, if compensation payments cannot completely quell grudges, then the collectibles cycle will be followed by a vendetta cycle. Because of this, it is possible that this system will reach an equilibrium state - reducing but not eliminating the vendetta cycle until more closely connected exchange networks emerge.

Properties of Collectibles

Ever since humans evolved into small, largely self-sufficient, feuding tribes, the use of collectibles reduced the need to keep track of favors and made possible the wealth transfer institutions we’ve discussed above;For most of our time as a species, these institutions solved problems far more important than the throughput problem of barter. In effect, collectibles provided a fundamental improvement in the operation of reciprocal altruism, extending the ways humans can cooperate to places that other species can’t.For them, reciprocal altruism is strictly limited by their unreliable memories. Some other species have large brains, build their own nests, and make and use tools. But no other species has produced a tool that provides such an important support for reciprocal altruism. Archaeological evidence suggests that this new historical process was already developed 40,000 years ago.

Menger called this first type of money “intermediate goods”—or what we’ll call “collectibles” in this article. Some artifacts that are useful for other scenarios (such as cutting) may also be used as collectibles. However, once tools related to wealth transfer become valuable, they will only be manufactured for their collectible properties. So what are these properties?

For a particular item to be selected as a valuable collectible, it must have the following properties (at least relative to less valuable products):

More secure and less susceptible to accidental loss and theft. For most of history, this property means that it can be carried around and easily hidden;

Its value attribute is more difficult to forge. An important subset of this attribute is extremely luxurious and almost unforgeable products, which are selected for the reasons we explained above.

Binance Launchpool has launched the 63rd project - Bio Protocol (BIO), a decentralized science (DeSci) management and liquidity protocol.

JinseFinance

JinseFinanceTrump's address deposited 1,325.16 ETH to the exchange between November and December 2023, an amount that would be worth $4.9 million if it had been held until today.

JinseFinance

JinseFinanceMicroStrategy’s Bitcoin vault is worth more than $40 billion after BTC surpassed $100,000.

JinseFinance

JinseFinanceFormer President Donald Trump revealed that he owns a whopping $5 million worth of cryptocurrency and has earned more than $7 million from his three NFT collections.

JinseFinance

JinseFinanceWhich L1 and L2 networks are driving the most revenue and earnings? Let’s dig into the data.

JinseFinance

JinseFinanceAthena Labs airdropped a total of $450 million worth of tokens to participants.

JinseFinance

JinseFinance"Earth From Another Sun" is a science fiction adventure game developed by Multiverse team.

JinseFinance

JinseFinanceIt is reported that Michael Saylor sold 3,882 to 5,000 MicroStrategy shares on certain days before the SEC approved the Bitcoin spot ETF, earning more than $20 million.

JinseFinance

JinseFinanceAmidst all the noise, no one seems to be seriously exploring how much money Binance was fined by the US government.

JinseFinance

JinseFinance JinseFinance

JinseFinance