Translated by: Liu Jiaolian

Jiaolian Note: This article is from Ryan McMaken of the "Mises Institute", and the original title is "The Real Story Behind the Fed’s "Soft Landing" Narrative". The Fed has been pushing back its expectations for rate cuts this year. How can we find buyers for the US debt that will expire and need to be replaced in the second half of the year? It may be the opposite of what you think. The Fed insists on high interest rates to make US debt easier to sell, thereby helping the US federal government complete deficit financing and support its huge expenditures such as domestic social welfare and foreign war aid. Once the Fed presses the interest rate cut button, the capital flowing back to the United States will be scattered, and there will be no one to take over the huge amount of US debt. In order to add a double insurance, the Federal Reserve has quietly started to slow down the reduction of its balance sheet in June, so that it can personally buy US debt and promote US debt sales.

What is "harvest"? The word "harvest" is composed of "collect" and "reap". Harvest and harvest, harvest first and harvest later. If you harvest but don't harvest, or want to harvest but don't harvest, it's a failure of harvest. In this round of interest rate hikes and tightening, the Federal Reserve first used a combination of high interest rate inducement and geopolitical turmoil to complete the "harvest", bringing back a large amount of US dollar capital to the country and letting them flow back to the US bond or US stock market. The main task now is to take advantage of the last window period and harvest as much as possible. The so-called "harvest" is to drive the returning capital to US bonds, and use the US bond blank paper printed at zero cost to exchange your real money. If you want to change the "harvest" to a more elegant term, I think it should be the "capital misallocation" in the mouth of the masters of the Austrian School of Economics.

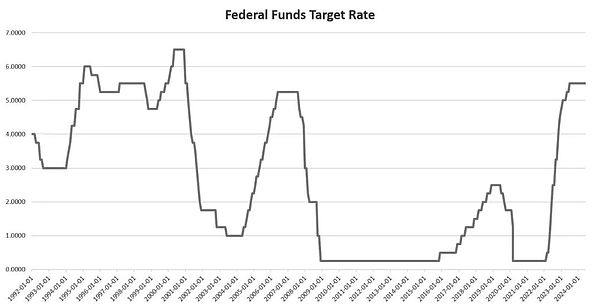

The Federal Open Market Committee (FOMC) of the Federal Reserve kept the policy target interest rate (federal funds rate) unchanged at 5.5% yesterday. Since July 2023, the target interest rate has remained unchanged at 5.5% - the Federal Reserve is waiting, hoping that everything will get better. At Wednesday's FOMC press conference, Powell continued to deliver the soothing message he has typically used in these press conferences over the past year in his prepared remarks. His overall message was that the economy is growing modestly but sustainably, employment trends are "strong," and inflation is moderating.

Powell then combined this economic view with the overall narrative of Fed policy, which is that the FOMC will remain stable until the committee believes that inflation is returning to its "longer-run inflation goal of 2 percent." Once the Fed is "confident" that the target inflation level has been achieved, then the Fed will begin to cut the target interest rate, which will put the economy back into another expansion phase.

Nevertheless, Powell and the FOMC insisted that there would be no major bumps and that a "soft landing" would be achieved. That is, Powell and the Fed repeatedly told the public that the Fed would ensure that the economy continued to grow at a solid pace and employment remained strong while pulling down price inflation.

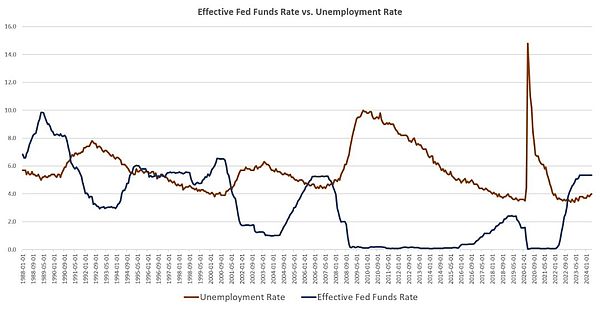

But there are two problems with this narrative: First, the Fed never actually did that—at least not at any time in the past 45 years. What actually happened was this: The Fed kept denying that a recession was coming until after it had already started. Then, the Fed cut rates only after unemployment had already started to rise.

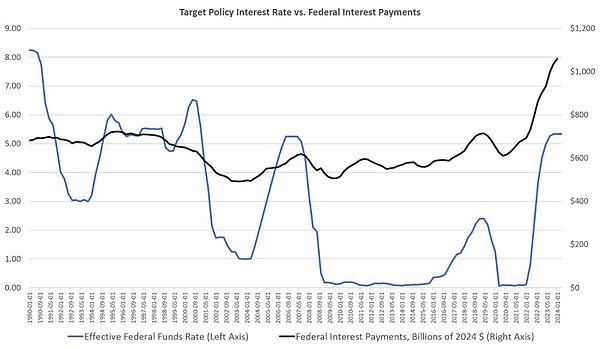

The second problem with this narrative is that the Fed is not motivated simply by concerns about jobs and the state of the economy. Yes, the Fed would have us believe that it cares only about a fair reading of the economic data, and that Fed policy is guided solely by that. That’s what the Fed means when it claims to be “data-driven.” In reality, the Fed cares about something else entirely: keeping interest rates down so that the federal government can continue to borrow large amounts of money at low yields. The more the federal government adds to its massive debt, the more pressure there is on the central bank to keep interest rates low, and keep them lower.

Yes, the Fed does fear rising prices because rising prices lead to political instability. When that fear wins out, the Fed lets interest rates rise. But the federal Treasury also wants the Fed to keep interest rates low for the elites in the federal government who go to great lengths to deficit spend. When the "need" for deficit spending wins out, the Fed forces interest rates down. These two goals are in direct opposition. Unfortunately, if the Fed has to choose between the two, it will likely choose the path of lower interest rates and higher prices.

How a "soft landing" actually happens

Let's first look at the myth of a "soft landing". Talk of a "soft landing" has been common in the U.S. media since at least the 2001 recession. For example, as early as July 2001, Bloomberg writers were speculating on how soft a soft landing would be. The end result was that there was no soft landing, and Dot-Com soon went bankrupt.

Prior to the Great Recession, talk of a "soft landing" was even more prominent. As early as mid-2008, months after the recession had already begun, Federal Reserve Chairman Ben Bernanke predicted a soft landing, no recession at all. In that recession, unemployment reached 9.9%.

We are seeing it all again now. Just look at the Fed’s Summary of Economic Projections (SEP) as Fed officials insist that there will be no recession and that economic growth will continue on a slow, steady, and positive trajectory. Yes, the SEP indicates that the Fed will soon begin to cut interest rates, but in this fantasy version of the economy, continued economic growth and solid employment will follow.

But real life doesn’t work that way. For example, notice that over the past 30+ years, the Fed’s rate cuts did not end a “soft landing” but actually preceded the worst period of unemployment. As you can see from the chart, cuts in the federal funds rate came months before a significant increase in unemployment. For example, the sharp rate cuts that began in 1990 were quickly followed by the 1991 recession. Similarly, the Fed began cutting rates in late 2000, and unemployment soon accelerated. This happened again in 2007, when unemployment began to rise soon after the Fed cut rates.

Of course, I am not saying that the reduction in the federal funds rate caused the increase in unemployment. I am saying that the Fed knew that the economy would not have a soft landing and that a recession was coming. This is why the Fed hit the rate cut button in a panic, hoping to shorten the impending recession.

This reality shows that there is absolutely no reason to believe the Fed's claim that everything is under control, and that the Fed will only cut rates after it has taken enough tightening measures to curb inflation before a recession without bursting the many bubbles that fuel employment and consumer spending.

In short, this is how the Fed operates: Fearing runaway inflation, the Fed will raise its target interest rate and generally "tighten" monetary policy. In the process, the Fed will insist that there will be no recession and that a "soft landing" is in the works. But in the end, it is clear that the economy has weakened significantly, and the Fed is either lying about the economy or simply wrong. At this point, the Fed does what it has always done in recent decades when it fears a recession: it eases monetary policy in the hope of blowing up a series of new bubbles and creating a new boom.

This is a far cry from the story of calm, cautious, and perfectly controlled monetary policy that the Fed would have us believe.

The Fed exists to fund the federal government with easy money

The second problem with Powell’s account is that the Fed is not motivated solely by concerns about jobs and the state of the economy. While it is nice to think that the Fed is primarily concerned with “regular people” and their job prospects, the reality is that the Fed is very concerned with keeping borrowing costs low so that Mitch McConnell, Nancy Pelosi, and others can continue to buy votes and fuel the war-like welfare state with massive deficit spending.

Keeping borrowing costs low by forcing interest rates down is more important now than at any time in decades. Over the past four years, the total federal debt has skyrocketed from $23 trillion to $34 trillion, an increase of $11 trillion. In an environment with interest rates close to zero, this might be manageable. However, when this debt is combined with rising interest rates, interest payments can quickly increase and take up an increasing share of the federal budget. If the government is not careful, it could face a sovereign debt crisis.

When the Fed can force interest rates down without worrying about runaway inflation, rising debt is less of a pressing concern. As we can see from the chart, the rapid rise in federal debt after the Great Recession did not result in a big increase in interest costs. However, that was during a period of very low interest rates. However, since 2022, the interest cost of the debt has risen sharply as the Fed has been forced to allow interest rates to rise.

In fact, interest costs have more than doubled since 2021. However, we haven't even seen the full impact of rising debt and rising interest rates. In the past few years, interest costs have been somewhat contained because federal debt is not due all at once. Yet, by 2024, nearly $9 trillion worth of federal debt will mature. This will need to be replaced with new debt that will need to be repaid at a higher interest rate (i.e., a higher yield) than the maturing debt. Add in the $2 trillion or so of new debt in 2024, and the federal government will need someone to buy more than $10 trillion worth of federal debt. With so much debt, one would hope that the Fed would help the federal government somehow keep interest rates from rising further. This would require the Fed to go into the market and buy up large amounts of debt to keep yields down.

In other words, political realities will mean that the Fed will have to accept new rate cuts regardless of whether price inflation is at its 2% target. Whether or not that is the case, the Fed will say that price increases have reached “target.” Since the Fed now defines its 2% target in terms of an average and a long-term trend, the Fed only has to say that it has determined that the “trend” points to lower price inflation.

Then, yes, the Fed can do what really matters to the federal government: mop up the federal deficit by forcing interest rates down.

Yesterday, Jerome Powell performed the usual song and dance that underlies the central bank’s political legitimacy: claiming that it is managing the economy deftly while simultaneously claiming that it cares deeply about the daily struggles of ordinary people facing the ravages of rising prices. The reality behind the charade is quite different.

Brian

Brian

Brian

Brian Davin

Davin YouQuan

YouQuan Brian

Brian Aaron

Aaron Kikyo

Kikyo Catherine

Catherine Catherine

Catherine Brian

Brian Kikyo

Kikyo