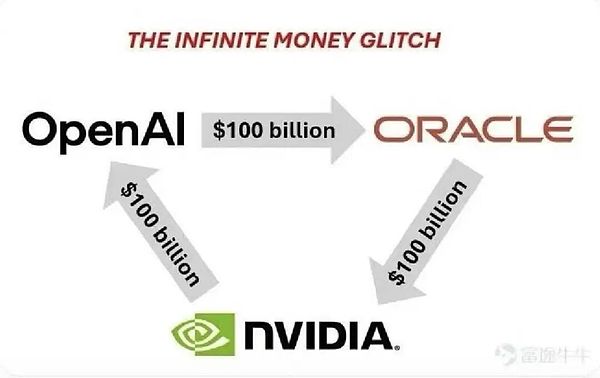

Recently, there is a joke circulating in the U.S. stock market:

“OpenAI invested $100 billion in Oracle to buy cloud computing services; Oracle invested $100 billion in Nvidia to buy graphics cards; Nvidia invested another $100 billion in OpenAI to lay out the AI system. Question: who actually paid the $100 billion?”

Oracle CEO Safra Catz bluntly stated: "The vast majority of our capital expenditure investments are used to purchase revenue-generating equipment that will go into the data center."

These "revenue-generating equipment" are mainly Nvidia's H100, H200 and the latest Blackwell chips.

Oracle has become one of Nvidia's largest customers.

Third Ring: Nvidia Returns the Favor

While Oracle was frantically purchasing chips, Nvidia announced a surprising decision: a $100 billion investment to support OpenAI in building a 10-gigawatt AI data center.

This investment will be made in phases, with Nvidia contributing corresponding funds each time OpenAI deploys 1 gigawatt of computing power. The first phase is scheduled to launch in the second half of 2026, using Nvidia's Vera Rubin platform.

Nvidia CEO Jensen Huang said in an interview: "10 gigawatts of data center capacity is equivalent to 4 to 5 million GPUs, which is roughly our full-year shipments this year."

At this point, a perfect capital cycle has been formed:

OpenAI pays Oracle to buy computing power, Oracle uses the money to buy chips from Nvidia, and Nvidia then invests the money it earns in OpenAI. A wealth amplifier between the virtual and the real: A $300 billion long-term contract led to a single-day increase in Oracle's market capitalization of over $250 billion, while a $100 billion investment led to a single-day increase in Nvidia's stock price of $170 billion. The three companies supported and endorsed each other, creating a resonance in stock prices. There's a rationale behind the stock price rise. For the capital market, future certainty is the most scarce commodity. Oracle's contract with OpenAI locks in a portion of its cloud revenue for the next five years, naturally leading investors to assign a higher valuation. Furthermore, Nvidia is using "GW" (gigawatts) as its unit of measurement. One GW is roughly equivalent to the size of a super data center. Ten GW means Nvidia and OpenAI are building a next-generation AI factory. This new narrative is more imaginative than simply "how many GPUs were purchased," and it's easily swayed by the market. Nvidia's investment in OpenAI effectively says, "I recognize it as a future super customer." OpenAI's contract with Oracle effectively says, "Oracle has the ability to support my future cloud computing needs," allowing OpenAI to secure more funding. Oracle's purchase of Nvidia GPUs effectively signals that "Nvidia's chips are in short supply." This is a stable and thriving industry chain. This cycle appears flawless, but a closer look reveals its subtleties. OpenAI currently generates approximately $10 billion in annual revenue, but has pledged to pay Oracle $60 billion annually. How will this massive gap be filled? The answer lies in round after round of funding. In April, OpenAI secured $40 billion in funding and expects to continue raising more. In reality, OpenAI uses investor funds to pay Oracle, Oracle uses that money to buy Nvidia chips, and Nvidia reinvests some of the proceeds back into OpenAI. It's a circular system driven by external capital. Furthermore, most of these astronomical contracts are based on "commitments" rather than immediate delivery, and can be delayed, renegotiated, or even canceled under certain conditions. The market sees promised figures, not actual cash flow.

This is the magic of modern financial markets:

expectations and commitments can create exponential wealth effects. Who will pay the bill?

Back to the original question of the joke: "Who actually paid the 100 billion?"

The answer is investors and debt markets. SoftBank, Microsoft, Thrive Capital, and other investment institutions are the direct payers in this game. They have poured tens of billions of dollars into OpenAI, propping up the entire capital cycle. Furthermore, banks and bond investors have also provided financial support for Oracle's expansion. Ordinary people holding related stocks and ETFs are the "silent payers" at the end of the chain. This AI capital rotation game is essentially a form of financial engineering in the AI era. It exploits the market's optimistic expectations for the future of AI to create a self-reinforcing investment cycle. In this cycle, everyone wins: OpenAI gains computing power, Oracle secures orders, and Nvidia gains sales and investment opportunities. Shareholders rejoice as their paper wealth grows. However, this joy is based on a single premise: that the future commercialization of AI can support these astronomical investments. If this premise is shaken, this beautiful cycle could turn into a dangerous spiral. Ultimately, the payer for this game is every investor who believes in the future of AI, using today's money to bet on tomorrow's AI era. Hopefully, the music won't stop. Conflict of Interest: The author holds shares in Nvidia and AMD.

Jixu

Jixu

Jixu

Jixu Kikyo

Kikyo Hui Xin

Hui Xin Alex

Alex Catherine

Catherine Clement

Clement Jasper

Jasper Jixu

Jixu Hui Xin

Hui Xin YouQuan

YouQuan