Author: Vitalik, founder of Ethereum; Translator: Deng Tong, Golden Finance

Recently, I finished reading (or rather, listened to audio) two major history books that present the Bitcoin block size debate of the 2010s from two extremes:

Jonathan Beer’s The Block Size War, which tells the story from the perspective of those who support small blocks;

Roger Vere and Steve Patterson’s Hijacking Bitcoin, which tells the story from the perspective of those who support large blocks.

It was fascinating to read these two histories of events that I personally experienced and even participated in to some extent. While I knew most of the events that took place, and both sides’ views on the nature of the conflict, there were still some interesting parts that I didn’t know about or had completely forgotten, and it was fun to look at the situation with fresh eyes. Was I a “big blocker” at the time, albeit a pragmatic centrist blocker who opposed extreme increases or absolutely advocated that fees should never go significantly above zero? Do I still stand by the views I held at the time? I look forward to finding out.

What do small blockers think of the block size war, as told by Jonathan Bier?

The original debate over the block size war revolved around a simple question: Should Bitcoin undergo a hard fork, raising the block size limit from the then-current 1MB to a higher value to allow Bitcoin to process more transactions, thereby reducing fees, but at the cost of making the chain more difficult and expensive to run nodes and validate? “[If the blocksize was bigger] you’d need a large datacenter to run a node, and you wouldn’t be able to run anonymously” — this is the key argument made in a video by Peter Todd arguing for keeping the blocksize small.

“[If the blocksize was bigger] you’d need a large datacenter to run a node, and you wouldn’t be able to run anonymously” — this is the key argument made in a video by Peter Todd arguing for keeping the blocksize small.

The impression I got from Bill’s book is that while small blockers do care about this issue, and tend to take a conservative approach of increasing the blocksize only a little to ensure that it’s still easy to run a node, they’re more concerned about how protocol-level issues like this are decided more generally. In their view, changes to the protocol (especially “hard forks”) should happen rarely and only with a high degree of consensus among the protocol’s users.

Bitcoin isn’t trying to compete with payment processors — there are already plenty of them. Instead, Bitcoin is trying to be something far more unique and special: an entirely new kind of money, one that is not controlled by a central organization and a central bank. If Bitcoin starts to have a highly active governance structure (which would be necessary to deal with controversial block size parameter adjustments) or becomes susceptible to coordinated manipulation by miners, exchanges, or other large companies, it will lose this valuable unique advantage forever.

In Bill’s view, big blockers offend small blockers most strongly precisely because they often try to unite a relatively small number of large players to legitimize and promote the changes they want — something that is at odds with small blockers’ views on how governance should be conducted.

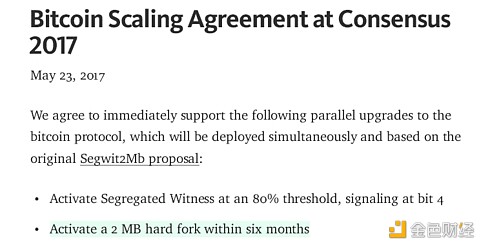

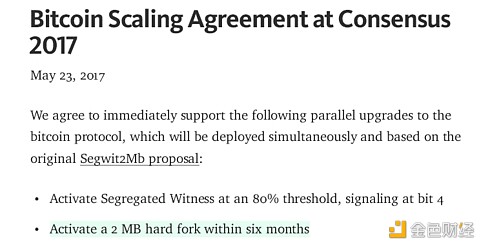

The New York Agreement was signed by major Bitcoin exchanges, payment processors, miners and other companies in 2017. Small blockers see it as a key example of an attempt to transform Bitcoin from user rule to corporate group rule.

How do big blockers view the block size dispute in Roger Ver's account?

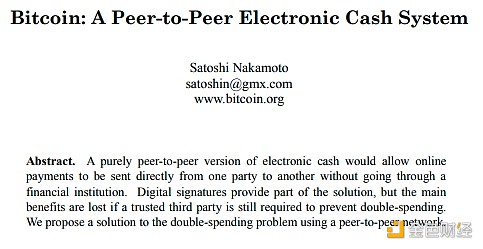

Big blockers often focus on a key underlying question: What should Bitcoin be? Should it be a store of value - digital gold, or a means of payment - digital cash? For them, it was clear to everyone from the beginning that the original vision, and the vision that big blockers all agreed on, was digital cash. The white paper even said so!

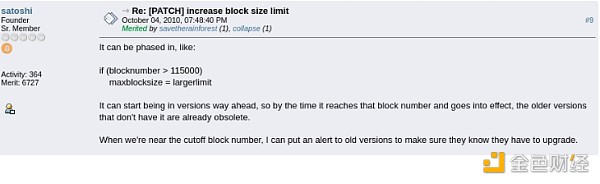

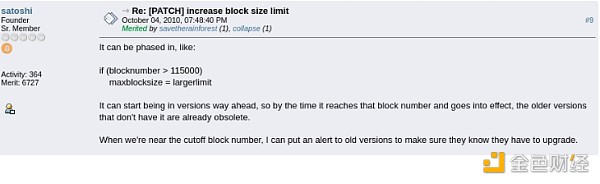

Big block supporters also often cite two other things written by Satoshi Nakamoto:

The simplified payment verification section in the white paper, which talks about how once blocks become very large, individual users can use Merkle proofs to verify that their payments are included without having to verify the entire chain.

Bitcoin Topic quotes a passage advocating a hard fork to gradually increase the block size:

For them, the shift from a focus on digital cash to digital gold was a turning point, one that was unanimously agreed upon by a small, tight-knit group of core developers, who then felt that because they had thought about the issue and reached a conclusion internally, they had the right to impose their views on the entire project.

The small blockers did offer a solution for how Bitcoin could be both cash and gold — namely, Bitcoin becomes a “Layer 1” that focuses on being gold, while “Layer 2” protocols built on top of Bitcoin, such as the Lightning Network, provide cheap payments without using the blockchain for every transaction. However, these solutions are so inadequate in practice that Weil devotes several chapters to a profound critique of them. For example, even if everyone switched to the Lightning Network, the block size would eventually need to be increased to attract hundreds of millions of users. Moreover, trustlessly receiving tokens on the Lightning Network requires having an online node, and ensuring that tokens are not stolen requires checking the chain weekly. Weil argues that these complexities will inevitably push users to interact with the Lightning Network in a centralized way.

What are the main differences in their views?

Weil’s description of the debate matches that of small blockers: both sides agree that small blockers value the convenience of running a node more, while big blockers value low transaction fees more. They both acknowledge that there are legitimate differences in beliefs, and that this difference is a key factor in the debate.

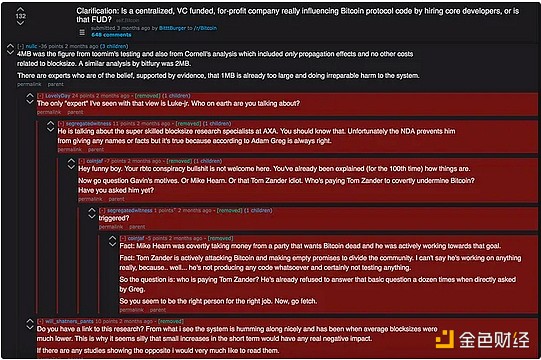

But Beer and Weil’s descriptions of most of the deeper underlying issues are very different. For Bill, the small blockers represent users against a small but powerful group of miners and exchanges that seek to seize control of the blockchain for their own benefit. Small blocks keep Bitcoin decentralized by ensuring that regular users can run nodes and validate the blockchain. For Weir, the big blockers represent users against a small but powerful group of venture capital firms (i.e. Blockstream) that have appointed themselves as high priests and profit from the Layer 2 solutions needed to build the small block roadmap. Big blocks keep Bitcoin decentralized by ensuring that users can continue to afford on-chain transactions without relying on centralized Layer 2 infrastructure.

The closest thing to the two sides “agreeing on the terms of the debate” in my opinion is that Bill’s book acknowledges that many big blockers are well-intentioned and even acknowledges that they have legitimate grievances about the behavior of forum moderators who support small blocks censoring opposing views, but often criticizes the big blockers for incompetence, while Weir’s book is more willing to attribute bad faith and even conspiracy theories to small blockers, but rarely criticizes their competence. This echoes a common political trope I’ve heard many times, which is “the right thinks the left is naive, and the left thinks the right is evil”.

How did I see the block size debate in my telling? How do I see it today?

Room 77 is a restaurant in Berlin that accepts Bitcoin payments. It is the center of Bitcoin Kiez, a district in Berlin where a large number of restaurants accept Bitcoin. Unfortunately, the Bitcoin payments dream died in the late aughts of the decade, and I attribute rising fees to the culprit.

When I experienced the Bitcoin block size debate firsthand, I generally sided with the big blockers. My sympathy for the big blockers centered around a few key points:

One of the key original promises of Bitcoin was digital cash, and high fees could kill that use case.While Layer 2 protocols could theoretically offer much lower fees, the entire concept is untested, and it would be highly irresponsible for small blockers to commit to a small block roadmap given how little they know about how the Lightning Network performs in practice. Today, real-world experience with the Lightning Network makes the pessimistic view even more prevalent.

I don’t buy the “meta” story about small blockers. Small blockers will often argue that “Bitcoin should be controlled by users” and that “users don’t support big blocks” but are never willing to identify any particular way to define who is a “user” or measure what they want. Big blockers have secretly tried to come up with at least three different ways to count users: hash power, public statements from prominent companies, and social media discourse, and small blockers have condemned each of them. Big blockers didn’t organize the New York Agreement because they like “cabals”; they organized the New York Agreement because small blockers insist that any controversial change requires “consensus” among “users”, and big blockers believe that only a statement signed by major stakeholders can truly achieve that.

The small blockers’ proposal to slightly increase the blocksize with Segwit is overly complex compared to a simple hard fork blocksize increase. Small blockers eventually embraced the “soft forks are good, hard forks are bad” philosophy (which I strongly disagree with), and designed a way to increase the blocksize to accommodate this rule, even though Bill admitted that the increased complexity was so severe that many big blockers could not understand the proposal. I feel that small blockers were not just “supporting caution”, they were arbitrarily choosing different types of caution, choosing one (no hard forks) at the expense of another (keeping the code and specs clean and simple) because it suited their agenda. Eventually, big blockers also abandoned the “clean and simple” philosophy in favor of ideas like Bitcoin Unlimited’s adaptive blocksize increase, a decision that Bill (rightfully) fiercely criticized.

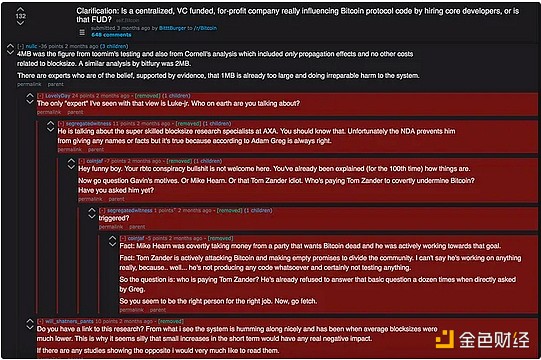

Small blocker supporters did resort to very uncool censorship behavior on social media to impose their views, culminating in Theymos’ infamous statement “If 90% of /r/Bitcoin users find these policies intolerable, then I hope these 90% of /r/Bitcoin users leave.”

Even relatively mild pro-big blocker posts were often deleted. Use custom CSS to make these deleted posts invisible.

Ver’s book focuses primarily on points 1 and 4, but also on point 3, as well as the theory of financially motivated malfeasance — namely that the small blockers founded a company called Blockstream that would build a Layer 2 protocol on top of Bitcoin, while promoting an ideology that Bitcoin Layer 1 should remain crippled, making these commercial Layer 2 networks necessary.Ver doesn’t dwell too much on the idea of how Bitcoin should be governed, because for him, the answer “Bitcoin is governed by miners” is already satisfactory. I don’t agree with either side on this: I find both the vague “we reject truly defined user consensus” and the extreme “miners should control everything because they have aligned incentives” to be unreasonable.

At the same time, I remember getting really frustrated with the big blockers at key points, and these arguments echo Bier’s book. One of the worst-case scenarios (both my and Bier agree on) is that the big blockers never agree on any realistic principle for the block size limit. A common view is that “block size is determined by the market” — meaning that miners should produce blocks as they wish, and other miners can choose to accept or reject those blocks. I strongly disagree with this view, and point out that saying that the mechanism is the market is a huge stretch of the concept of “market”. Ultimately, when the big blockers split off into their own independent chain (Bitcoin Cash), they finally abandoned this view and added a 32MB block size limit.

At the time, I did have a principled reasoning for how to decide on the block size limit. To quote from a 2018 article:

Bitcoin tends to maximize the predictability of the cost of reading the blockchain at the expense of making the cost of writing to the blockchain as predictable as possible, with predictably very healthy results for the former metric and very bad results for the latter. Ethereum and its current governance model leans towards predictability somewhere in the middle of the two.

I later repeated this sentiment in a tweet in 2022. Essentially, the idea is that we should balance increasing the cost of writing to the chain (i.e. transaction fees) with the cost of reading from the chain (i.e. software requirements for nodes). Ideally, if demand for using the blockchain increased 100x, we should split the pain in half and have 10x more blocks and 10x more fees (the demand elasticity for transaction fees is close enough to 1 for this to be feasible in practice). Ethereum actually ended up taking a medium-block approach: since its launch in 2015, the chain’s capacity has increased by about 5.3 times (perhaps 7 times if you include calldata repricing and blobs), while fees have increased from almost zero to a significant but not too high level. However, this compromise-oriented (or “concave”) approach never caught on with either faction; perhaps one side felt it was too “centrally planned” and the other felt it was too “indecisive”. I feel like the big blockers are more responsible in this regard than the small blockers; the small blockers were initially open to modest increases in block size (e.g. Adam Back's 2/4/8 plan), while the big blockers were unwilling to compromise, and they quickly went from advocating for a one-time increase in block size to a specific larger number to advocating for an overarching philosophy that almost any non-trivial limit on block size is illegal.

The big blockers also began advocating that miners should be in charge of Bitcoin - an philosophy Bill effectively criticized by pointing out that if miners tried to change the rules of the protocol to do something other than increase the block size - like give themselves more rewards - they would probably quickly abandon their views.

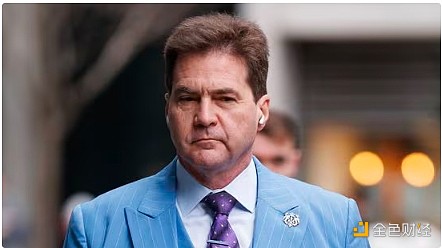

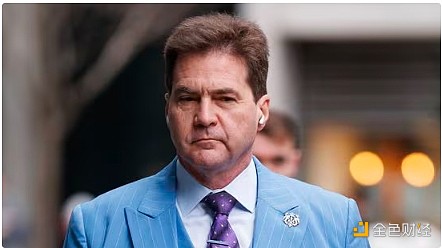

One of the big criticisms of the big blockers in Bill's book is that they have repeatedly shown incompetence. Bitcoin Classic was not well-coded, Bitcoin Unlimited was overly complex, didn't have sweep protection for a long time, didn't seem to realize that this choice would greatly hurt their chances of success (!!), and they had serious security vulnerabilities. They loudly call for multiple Bitcoin software implementations — a principle I agree with, and which Ethereum has also adopted — but their “alternative clients” are really just forks of Bitcoin Core that change only a few lines of code to implement the block size increase. In Bill’s account, their repeated gaffes in both code and economics ultimately led to more and more supporters turning away from them over time. They were further discredited by the major big block proponents being fraudulently claimed to be Satoshi by Craig Wright.

Craig Wright, a fraudster posing as Satoshi. He often uses legal threats to silence criticism, which is why my fork is the largest online copy in the Cult of Craig repository, which documents the evidence proving he is a fraud. Unfortunately, many big blockers are deceived by Craig's antics because Craig toes the big block party line and says what big blockers want to hear.

Overall, after reading both books, I found myself agreeing more with Weir on the macro issues, but more with Bill on the specifics. In my opinion, the big blockers are right on the core issue that blocks need to be larger, and that this is best achieved through a simple and clean hard fork as described by Satoshi, but the small blockers make far fewer embarrassing technical mistakes and have fewer cases of ridiculous results if you try to push their position to its logical conclusion.

The Block Size Debate Is a One-Sided Capability Trap

The combined impression I got from reading both books was a political tragedy that I feel I have seen again and again in a variety of contexts, including crypto, corporate, and national politics:

One side monopolizes all the capable people, but uses its power to promote narrow and biased views; the other side correctly recognizes that something is wrong, but focuses on opposing it and fails to develop the technical ability to execute independently.

In many of these cases, the first group is criticized as authoritarian, but when you ask its supporters (usually many) why they support it, their answer is that the other side only knows how to complain; if they actually gain power, they will be completely defeated within a few days.

This is not the fault of the opposition to some extent: it is difficult to be good at execution without a platform for execution and the experience of gaining experience. But in the block size debate, the big blockers seem to be largely unaware of the need for execution capabilities - they think they can only win by being right about the block size issue. The big blockers ended up paying a heavy price for their focus on opposition rather than building in multiple ways: even when they split into their own chain with Bitcoin Cash, they ended up splitting twice more before the community finally stabilized.

I call this problem the one-sided capacity trap. It seems to be a fundamental problem for anyone trying to build a political entity, project, or community that they hope is democratic or pluralistic. Smart people want to work with other smart people. If two different groups are roughly equal, people will gravitate toward the group that aligns more with their values, and the balance will stabilize. But if you go too far in one direction, the balance will shift to the other, and it seems difficult to get it back. To some extent, the one-sided capacity trap can be mitigated as long as the opposition is aware that there is a problem and that they have to consciously build capacity. Often, opposition movements don't even get that far. But sometimes it's not enough to just recognize the problem. We would benefit greatly from stronger and more in-depth ways to prevent and escape the one-sided capacity trap.

Less Conflict, More Technology

One very glaring omission from both books struck me as odd: the term “ZK-SNARK” appears exactly zero times in either book. There’s not much excuse for this: even by the mid-2010s, ZK-SNARKs and their potential to revolutionize scalability (and privacy) were widely known. Zcash launched in October 2016. Gregory Maxwell explored the scalability implications of ZK-SNARKs a little in 2013, but they don’t seem to be considered at all in discussions of Bitcoin’s future roadmap.

The ultimate way to ease tensions is not compromise, but new technology: discovering fundamentally new ways to give both sides more of what they want at the same time. We’ve seen several examples of this in Ethereum. A few examples that come to mind are:

Justin Drake’s push for BLS aggregation allows Ethereum’s proof-of-stake to handle more validators, reducing the minimum stake balance from 1500 to 32 with little downside. More recently, work on signature consolidation is expected to further this goal.

EIP-7702 achieves the goals of ERC-3074 and has significant forward compatibility with smart contract wallets, helping to mitigate long-standing disputes.

Multidimensional gas, starting with its implementation of blobs, has helped improve Ethereum’s ability to hold aggregated data without increasing the worst-case block size, thereby minimizing security risks.

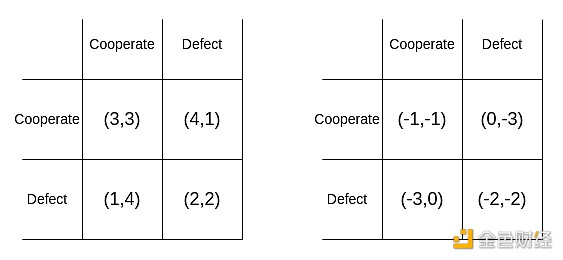

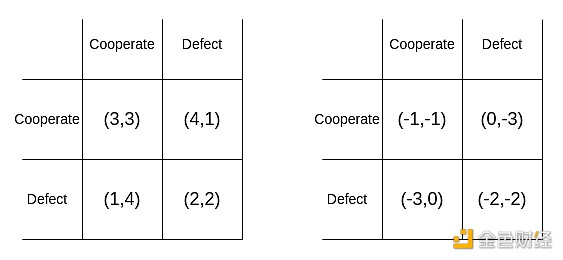

When an ecosystem stops accepting new technology, it inevitably stagnates and becomes more contentious: a political debate between “I get 10 apples” and “you get 10 apples” is inherently less conflict-provoking than a debate between “I give up 10 apples” and “you give up 10 apples.” Losses are more painful than gains, and people are more willing to “break” their shared political commons to avoid losses. This is a key reason why I’m so uncomfortable with ideas like degrowth and the idea that we can’t solve social problems with technological solutions: there are pretty good reasons to believe that fighting over who wins more than fighting over who loses less is indeed more conducive to social harmony.

From an economic theory perspective, there is no difference between the two dilemmas: the game on the right can be seen as the game on the left plus a single (irrelevant) step in which both players lose four points no matter how they act. But in human psychology, the two games can be very different.

A key question for the future development of Bitcoin is whether it can become a technologically leading ecosystem. The development of Inscriptions and the subsequent BitVM has created new possibilities for Layer 2, improving on what can be done with the Lightning Network. Hopefully, Udi Wertheimer is right in his theory that ETH getting an ETF means the death of Saylorism and a renewed appreciation for what Bitcoin needs to improve technically.

Why do I care?

I care about studying Bitcoin’s successes and failures not because I want to disparage Bitcoin to elevate Ethereum; in fact, as someone who loves trying to understand social and political issues, I find one thing about Bitcoin is that it’s sociologically complex enough that its internal debates and divisions are so rich and fascinating that you could write two books about it. I care about analyzing these issues because Ethereum and every other digital (and even physical) community I care about can learn a lot from understanding what happened, what went well, and what could be done better.

Ethereum’s focus on client diversity stems from observing Bitcoin’s failures with only one client team. Its Layer 2 version stems from understanding how Bitcoin’s limitations lead to limits on what kind of Layer 2 with trust properties can be built on top of it. More generally, Ethereum’s explicit attempt to foster a diverse ecosystem is largely an attempt to avoid the one-sided capability trap.

Another example that comes to mind is the Net State movement. This is a new strategy for digital splintering that allows communities with aligned values to gain a degree of independence from mainstream society and build their own visions of the cultural and technological future. But the experience of (post-fork) Bitcoin Cash shows that movements organized around forking solutions have a common failure mode: they end up splitting again and again, and never really working together. The lessons of Bitcoin Cash extend far beyond Bitcoin Cash itself. Zuzalu is in some ways my own attempt to push for change in this direction.

I recommend reading Bill’s The Block Size Wars and Will’s Hijacking Bitcoin to understand one of the defining moments in Bitcoin’s history. In particular, I recommend reading both books with the mindset that this isn’t just about Bitcoin — rather, it was the first real high-stakes civil war for a “digital state,” and these experiences hold important lessons for other digital states we’ll be building in the coming decades.

JinseFinance

JinseFinance