Author: Techub Selected Compilation

Written by: Joel John, Decentralised.co

Compiled by: Yangz, Techub News

Money governs everything around us. When people start discussing fundamentals again, the market is probably in a bad place.

This article raises a simple question, should tokens generate income? If so, should teams buy back their own tokens? Like most things, there is no clear answer to this question. The road ahead needs to be paved with frank conversations.

Life is just a game called capitalism

This article was inspired by a series of conversations with Ganesh Swami, co-founder of Covalent, a blockchain data query and indexing platform. It covers the seasonality of protocol revenue, evolving business models, and whether token buybacks are the best use of protocol capital. It also complements my article last Tuesday about the current stagnation in the cryptocurrency industry.

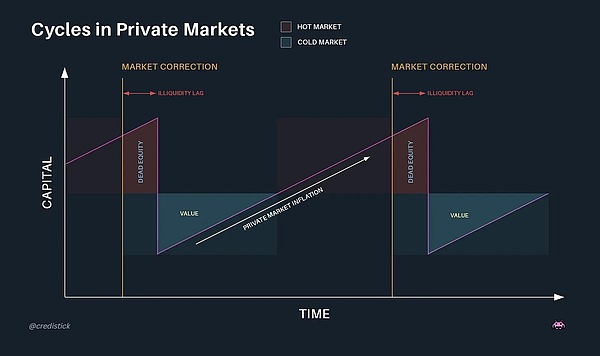

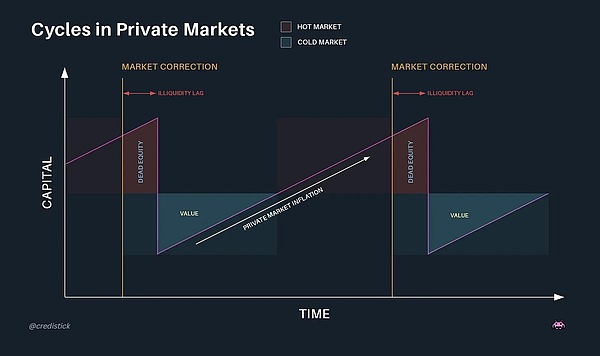

Private equity capital markets such as venture capital always swing between excess liquidity and liquidity scarcity. When these assets become liquid assets and external funds continue to pour in, industry optimism tends to drive prices higher. Think about all the new IPOs, or token issuances, this newfound liquidity will allow investors to take on more risk, but in turn will drive the birth of a new generation of companies. When asset prices rise, investors will turn their funds to early-stage applications, hoping to get higher returns than benchmarks such as Ethereum and SOL.

This phenomenon is a feature of the market, not a problem.

Source: Dan Gray, Chief Researcher at Equidam

Liquidity in the cryptocurrency industry follows a cyclical cycle marked by the halving of Bitcoin's block reward. From historical data, market rebounds usually occur within six months after the halving. In 2024, inflows into Bitcoin spot ETFs and Michael Saylor’s massive purchases (spending a total of $22.1 billion on Bitcoin last year) became a “reservoir” for Bitcoin. However, the rise in Bitcoin prices did not lead to an overall rebound in small-cap altcoins.

We are currently in a period of tight capital liquidity, with capital allocators’ attention being scattered across thousands of assets, and founders who have been working on tokens for years are struggling to find the meaning of it all, “Since launching a meme asset can bring more economic benefits, why bother to build real applications?”

In previous cycles, L2 tokens enjoyed a premium for perceived potential value, thanks to exchange listings and venture capital support. However, as more participants flock to the market, this perception and its valuation premium are being eliminated. As a result, L2’s token value has declined, which in turn limits their ability to subsidize smaller products with grants or token revenue. In addition, overvaluation in turn forces founders to ask the old question that plagues all economic activities: where does the revenue come from?

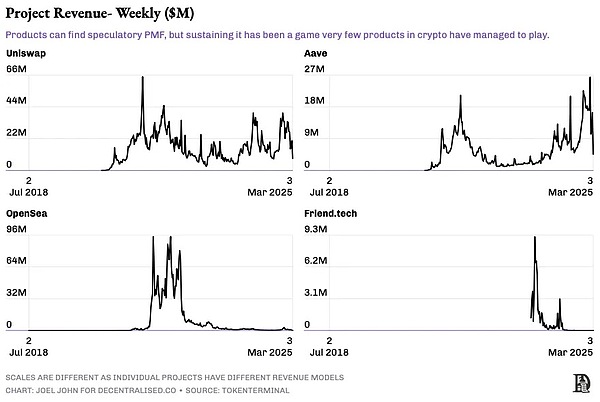

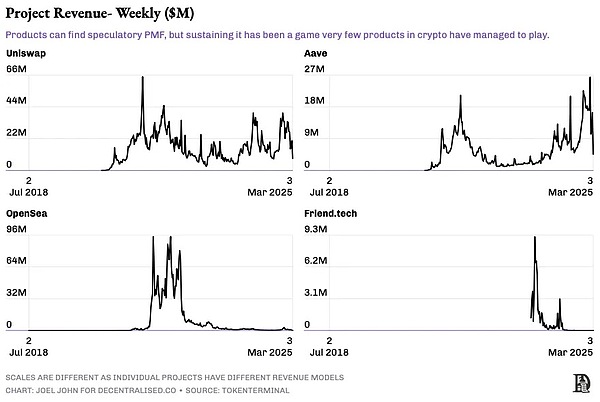

How cryptocurrency project revenue works

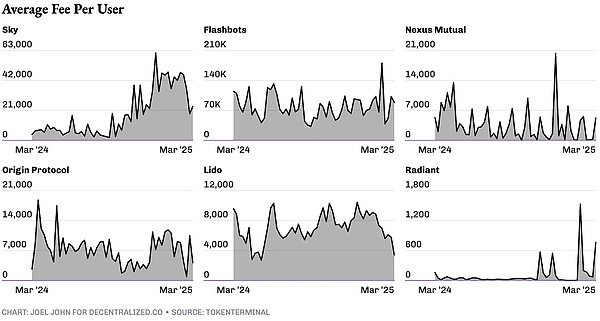

The above figure explains well how cryptocurrency project revenue typically works. For most products, Aave and Uniswap are undoubtedly ideal templates. With the advantage of early market entry and the "Lindy effect", these two projects have maintained stable fee income for many years. Uniswap can even generate revenue by adding front-end fees, which perfectly confirms consumer preferences. Uniswap is to decentralized exchanges as Google is to search engines.

In contrast, Friend.tech and OpenSea have seasonal revenue. For example, the “Summer of NFTs” lasted two quarters, while the speculative boom in Social-Fi lasted only two months. Speculative revenue is understandable for some products, provided that the revenue scale is large enough and consistent with the original intention of the product. Currently, many meme trading platforms have joined the club of over $100 million in fee revenue. This scale of revenue is usually only achievable for most founders through token sales or acquisitions. This level of success is not common for most founders who focus on developing infrastructure rather than consumer applications, and the revenue dynamics of infrastructure are different.

Between 2018 and 2021, venture capital firms provided a lot of funding for developer tools, expecting developers to acquire a large number of users. But by 2024, the crypto ecosystem has undergone two major shifts:

First, smart contracts have achieved infinite scalability with limited human intervention. Today, Uniswap and OpenSea no longer need to expand their teams in proportion to trading volume.

Second, progress in large language models (LLMs) and artificial intelligence has reduced the need to invest in cryptocurrency developer tools. Therefore, as an asset class, it is at a "reckoning moment".

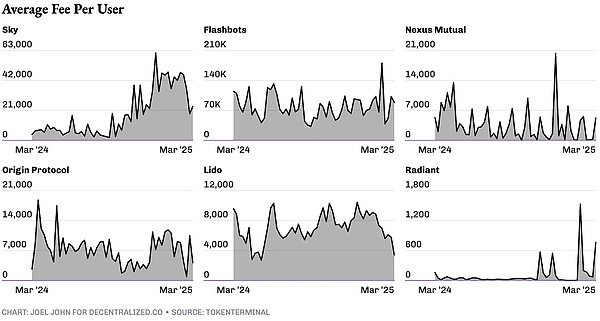

In Web2, API-based subscription models work because there are a large number of online users. However, Web3 is a smaller niche market, and only a few applications can scale to millions of users. Our advantage is that the average customer revenue per user is high. Based on the characteristics of blockchain that can make money flow, ordinary users in the cryptocurrency industry tend to spend more money at a higher frequency. Therefore, in the next 18 months, most companies will have to redesign their business models to generate revenue directly from users in the form of transaction fees.

Of course, this is not a new concept. Initially Stripe charged per API call, while Shopify charged a flat fee for subscriptions, but both platforms later switched to charging a percentage of revenue generated. For infrastructure providers, Web3 API charging is relatively simple and straightforward. They cannibalize the API market through a race to the bottom, or even offer free products until they reach a certain transaction volume, and then start negotiating revenue sharing. Of course, this is an ideal hypothetical situation.

As for what will happen in reality, Polymarket is an example. Currently, the UMA protocol token is tied to dispute cases and used to resolve them. The greater the number of prediction markets, the higher the probability of disputes, which directly drives demand for UMA tokens. In a trading model, the required margin can be a small percentage, such as 0.10% of the total bets. Assuming $1 billion is bet on the outcome of the presidential election, UMA can earn $1 million in revenue. In a hypothetical scenario, UMA can use this revenue to purchase and destroy its own tokens. This model has both advantages and challenges (which we will explore further later).

In addition to Polymarket, another example of a similar model is MetaMask. Through the wallet's embedded exchange function, it has currently traded approximately $36 billion in volume and has earned more than $300 million in revenue from exchange business alone. In addition, a similar model also applies to staking providers like Luganode, which can charge fees based on the amount of assets staked.

However, in a market where API call returns are decreasing, why would developers choose one infrastructure provider over another? If revenue sharing is required, why choose one oracle service over another? The answer lies in network effects. Data providers that support multiple blockchains, provide unparalleled data granularity, and can index new chains faster will be the first choice for new products. The same logic applies to transaction categories such as intent or gas-free exchange tools. The greater the number of blockchains supported, the lower the cost and the faster the speed, the more likely it is to attract new products because marginal efficiencies help retain users.

Token Buybacks and Burns

Linking token value to protocol revenue is nothing new. In recent weeks, several teams have announced mechanisms to buy back or burn native tokens in proportion to revenue. Among the notable ones are Sky, Ronin, Jito, Kaito, and Gearbox.

Token buybacks are similar to stock buybacks in the US stock market, and are essentially a way to return value to shareholders (token holders) without violating securities laws.

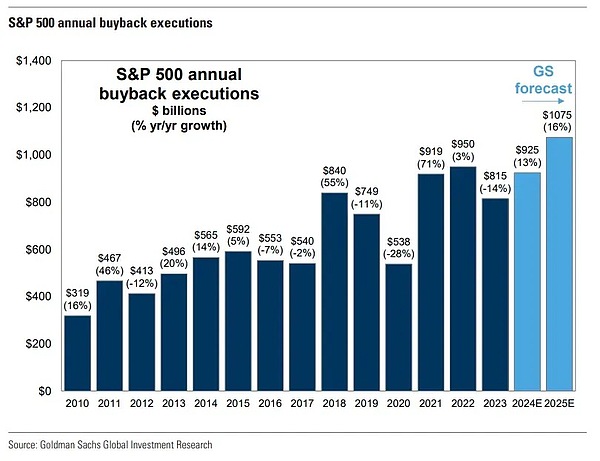

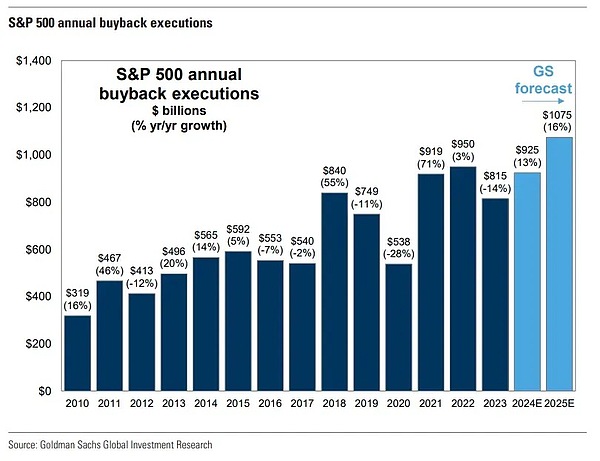

In 2024, the US market alone will spend about $790 billion on stock buybacks, up from $170 billion in 2000. Prior to 1982, stock buybacks were considered illegal. Apple alone has spent more than $800 billion buying back its own shares over the past decade. While it remains to be seen whether this trend will continue, we are seeing a clear split in the market between tokens that have cash flow and are willing to invest in their own value, and those that have neither.

Source: Bloomberg

For most early protocols or dApps, using revenue to buy back their own tokens may not be the best use of capital. One possible way to do this is to allocate enough funds to offset the dilution effect of new token issuance, which is exactly what the founder of Kaito recently explained about its token buyback method. Kaito is a centralized company that uses tokens to incentivize its user base. The company obtains centralized cash flow from corporate customers and uses part of the cash flow to execute token buybacks through market makers. The number of repurchased tokens is twice the number of newly issued tokens, which puts the network into a deflationary state.

Unlike Kaito, Ronin takes a different approach. The chain adjusts fees based on the number of transactions per block. During peak usage, a portion of network fees will flow into the Ronin treasury. This is a way to monopolize the supply of an asset without buying back tokens. In both cases, the founders designed mechanisms to tie value to economic activity on the network.

In future posts, we will delve deeper into the impact of these operations on the price and on-chain behavior of tokens participating in such activities. But for now, it is clear that as token valuations decline and the amount of venture capital flowing into the cryptocurrency industry decreases, more teams will have to compete for the marginal funds that flow into our ecosystem.

Given the core property of blockchains as “money rails,” most teams will move to a revenue model based on a percentage of transaction volume. When this happens, if the project team has already launched a token, they will have an incentive to implement a “buy back and burn” model. Teams that can successfully execute this strategy will be the winners of the liquid market, or they may buy their own tokens at extremely high valuations. The results of everything can only be known after the fact.

Of course, one day, all this discussion about price, earnings and revenue will become irrelevant. We will continue to throw money into various "dog Memecoins" and buy various "monkey NFTs". But looking at the current state of the market, most founders who are worried about survival have begun to have in-depth discussions around revenue and token destruction.

Catherine

Catherine