Why doesn’t Tether want its own blockchain?

Tether CEO Paolo Ardoino said in an interview. “Launching your own blockchain is probably not the right move. There are many very good blockchains.”

JinseFinance

JinseFinance

Original author: Steakhouse

"Recommendation: This article re-examines some core issues of the current ETH ecosystem Restaking, AVS and Liquid Restaking tracks, and predictively gives an analogous risk and return assessment framework. Enjoy!"

Trust is an essential component of economic activities and human cooperation. In corporate interactions, trust is mainly established through reputation and legal enforcement. A decentralized trust network is a new type of coordination mechanism that allows individuals to conduct remote transactions without the need for trusted intermediaries. Ethereum and the proof-of-stake system created the concept of collateralized cryptoeconomic security, in which native tokens are used as collateral by network providers to provide decentralized trust.

Restaking extends Ethereum’s cryptoeconomic security by creating a “marketplace for decentralized trust”. This is achieved by bringing together Ethereum’s restakers and validators (providers of decentralized trust) with seekers of decentralized trust AVS (Active Validation Services). Note that Ethereum itself is in principle an AVS. Other AVSs can bootstrap the creation of new decentralized trust networks by restaking, providing specific services.

Providers of restaking ETH must make a risk/reward assessment of the network for which they provide security collateral. Expected total return is an important component of cryptoeconomic security, as higher returns make it more attractive for providers of decentralized trust to participate in the network.

In this paper, we explore the landscape of restaking in order to price the restaking risk in these AVS networks, deriving a simplified value assessment framework. Our rough framework takes into account the “cost of trust” used in capital markets to price risk. Breaking down to: Trust Return = Price Return + Work Return + Restaking Return - Default Loss Restaking should evaluate available opportunities in a systematic way and determine if the return is commensurate with the risk. The market has very high expectations for restaking returns, which are priced in through multiple layers of points. Ultimately, we believe the market will have to face the reality of AVS monolithic economics and the affordability of its security budget. Restaking 101 What is AVS? Active Verification Service (AVS) is a business that requires a high degree of trust to provide utility, and earns trust through cryptographically secure mechanisms rather than traditional, centralized security models that rely on trusted intermediaries.

In the broadest sense, decentralized applications (dapps), smart contracts, and the blockchain itself are delivered securely through the crypto-economy. Many services rely on the default security model of some of the largest networks (such as Ethereum), which require services to conform to the standards of that network. However, some services may choose to create their own security models for a variety of reasons:

• Fine-grained customization of specific rules, features, pricing, or performance

• Complete sovereignty over governance and operational decisions

• Innovation or novel mechanisms at the consensus or other protocol layers

• Neutrality

• Trust assumptions and specific security requirements

Unfortunately, decentralized networks with native cryptoeconomic security can be expensive and complex to build from scratch. Indeed, the relative lack of success of many layer 1 blockchains demonstrates the high costs and coordination complexity required to bootstrap a decentralized cryptoeconomic security network with many distributed validators. Additionally, the token prices of many layer 1 blockchains are highly volatile, often leading to instability in the amount of cryptoeconomic security present in the network and driving up the long-term cost of capital for these projects. Source: stakerewards.com as of March 24, 2024 While inflation is not a good indicator of decentralization, it can be viewed as a useful signal as the network seeks to strike a balance with the number of validators it is trying to incentivize to join the network. In new, bootstrapped networks, such as Dymension, inflation is very high as a compensation to attract new stakers. Paying new validators to join the network is only a long-term sustainable expense if long-term network "yield growth" can overcome the effects of dilution.

What is Restaking?

Restaking is the re-staking of ETH LSD assets for new Active Validation Services (AVS) that impose new slashing conditions on capital. AVS can choose to "lease" their security from Ethereum stakers rather than bootstrapping an entirely new cryptoeconomic security network from scratch with their native tokens. Restaking allows ETH stakers to gain enhancements from a capital efficiency perspective while providing AVS with potentially more stable security that is no longer subject to the price volatility of their native tokens. Ethereum's vibrant economic and ecosystem activity makes ETH a superior, blue-chip collateral asset, similar to the concept of "hard currency".

There is an advantage to these services choosing to lease their security in "hard currency" rather than building an entirely new cryptoeconomic security system from scratch.

In a PoS security system, stakers accept the opportunity cost and price the risk of the tokens they must commit in order to validate the network. The network must provide a high enough return on staking in order to:

1) attract depositors;

2) offset the fixed costs of validators providing services. The more trust (staking) required to protect the service, the higher the cost of satisfying stakers' needs. In addition, the more value an AVS product service carries, the more security trust is required. In the monolithic economics of AVS, the cost of security is an expense.

The economics of AVS require a lot of capital to provide this level of security, which ultimately means that a lot of utility should be provided and corresponding cash flow should be earned from the service. AVS that otherwise cannot capture enough value will be forced to find creative ways to fill this expense, such as by increasing the inflation of the native token, or will eventually face the problem of business suspension.

The premise of re-staking is that it is cheaper to rent capital than to purchase or build staking locally. When pooled together, the size of the security and the cost of the security can indeed drive down fees. Like many physical inventory heavy businesses, leasing is often the right decision for early or immature businesses.

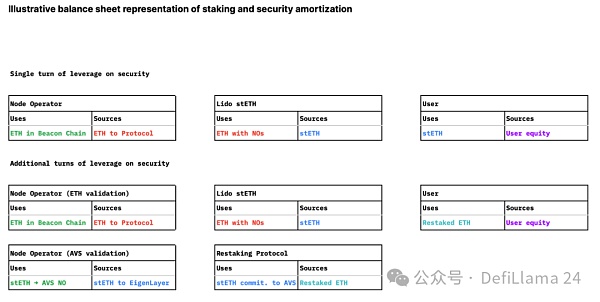

From a balance sheet perspective, we move from a linear, single-shot leverage of user equity to a multi-layered, leveraged security model with varying security demands and amortization of capital. This comes at the expense of increased leverage risk on the underlying collateral.

From an AVS perspective, leasing amortized security against ETH collateral is a form of financial engineering that looks a bit like debt relative to equity. We assume that demand for the security will be relatively inelastic because it is an exogenous variable.

The more assets an AVS secures, the higher the demand for collateral will be, increasing the cost of re-hypothecation, but there is no pressure to add more security for the same amount of assets - although there will likely be local panics where re-hypothecation becomes more expensive if security collateral is withdrawn.

The cost of security will be a balance of supply and demand for re-hypothecation fees. Assume that if an AVS cannot meet its payment obligations, re-hypothecators will have no incentive to post security collateral and will withdraw their pledge, making the price of new security higher. If there is a greater supply of re-hypothecated collateral, the cost of security should decrease, all else being equal, for both AVS and re-hypothecators.

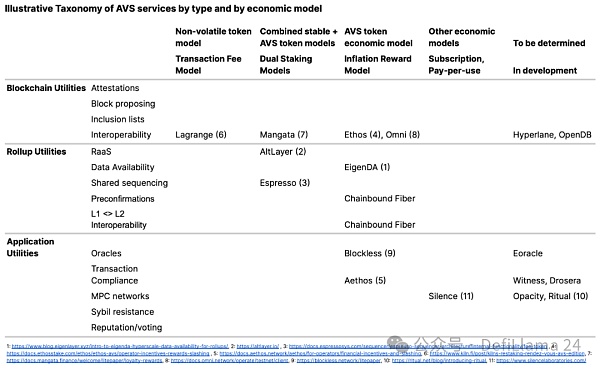

What are the different types of AVS?

At the time of writing, this is a bit of a fantasy, as no AVS are currently live, although some are expected to launch on mainnet soon. Therefore, the classification of AVS is quite speculative. However, we can imagine a scenario of virtual services and try to categorize them in a useful way to identify value and risk drivers. From an economic perspective, a relevant categorization might look at how AVS creates value and incentivizes participation.

The following is a non-exhaustive list of current AVS, as new types of services may emerge in the future with less reliance or relevance to the underlying Ethereum base layer.

We expect that re-staking fees and their relationship to the AVS monolithic economy will be the only source of truth about whether AVS can continue to rent security through re-staked ETH and generate attractive returns for re-stakers. The rewards received by re-stakers are also stacked on the axis of small to large risk and small to large reward variability.

The simplest way to assess whether AVS's pledged security model is sustainable is by drawing an analogy from the Debt Service Coverage Ratio (DSCR) in traditional business:

DSCR = Revenue / Total Debt

We can slightly adjust this to accommodate re-hypothecation and produce the Re-hypothecation Operating Affordability Ratio (ROAR):

ROAR = AVS Cash Revenue / Total Expenses of Security Rent Seeking

Where AVS Cash Revenue can be decomposed into:

AVS Cash Revenue = Profitability x Efficiency x TVL = AVS Revenue / Sales x Sales / Assets x Assets

Without any operating history of AVS, we cannot really judge right now what level of ROAR is adequate. Simply put, an AVS must be able to structurally afford the security it requires, or it needs to rethink its security needs and find another solution. If an AVS is too small to afford to pay for ETH collateral backing L1 validation in hard currency, one way to bridge the gap is through the issuance of an equity-like native token until they can reach a scale that mitigates dilution. The proportion of fees paid in non-volatile tokens or through native token dilution will determine whether the re-stakeholder should structure the AVS's choices from the perspective of a creditor or an equity investor.

However, this introduces a concept of yield sustainability similar to that faced by a new layer 1 blockchain, which must increase its issuance to pay for new security. The reflexive danger of native token issuance is that few cryptoeconomic protocols have found a sustainable balance between issuance and issued tokens. Ethereum is one of the few major ones at the network level.

The tendency of AVS to issue their own tokens may be due, at least in part, to market inefficiencies that may exist in crypto markets, which reduce the effective cost of capital for native tokens relative to other sources of capital.

While in traditional commerce, equity issuance would be a hotly debated issue and is often the most expensive source of funding for a business, crypto appears to benefit from over-inflated P/E ratios, which overall reduces the cost of capital for new tokens.

To assess whether such issuance is sustainable long-term, re-stakers must determine whether the price return on the native token (earnings growth x multiple growth x supply change) will overcome the initial inflationary period. Bootstrapping of leased security is an operational lever that can help AVS scale faster than if they had to bootstrap their own L1 network themselves. Distributing native tokens also has the additional market benefit of potentially binding participants in the AVS ecosystem together in the long term.

However, there is still a bit of déjà vu here, as the main purpose of re-staking is to provide lower-cost security through amortized collateral and avoid the inflationary costs of bootstrapping a brand new L1 from scratch to obtain cryptoeconomic security.

How to measure the cost of trust?

In traditional finance, the total return of equity investors is the sum of price return and dividend yield. That is:

Total return = price return + dividend yield

Price return can be further decomposed into 3 value drivers:

Price return = earnings growth x earnings multiple growth x token supply change

Dividend yield is an additional medium-term cash flow granted to capital providers. All capital providers typically receive the same dividend yield.

In a decentralized trust network like Ethereum, there is a medium-term cash flow that is awarded to work providers. Work in the context of Ethereum is done by providing 32 ETH as collateral for cryptoeconomic security to participate in validating transactions. Unlike dividend yield, work yield depends on whether ETH holders stake.

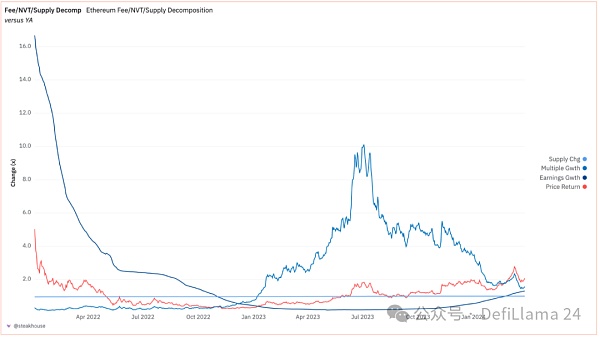

Total Return = ETH Price Return + Work Yield

This "work yield" is essentially negative for non-stakers because they are diluted by the new issuance of ETH rewarded to stakers. In a way, stakers can be considered preferred shareholders who are entitled to dividend payments, while non-stakers can be considered common shareholders who suffer dilution. A hypothetical example of the impact of whether or not an ETH holder stakes on their total return is in the appendix. Meanwhile, the chart below shows the price return breakdown of ETH, including the change in gas fees in USD, the change in the network multiple, and the change in supply growth. Multiplying these three components together equals the price return of ETH over a given period.

Source: Dune. https://tinyurl.com/2yzvxk4u

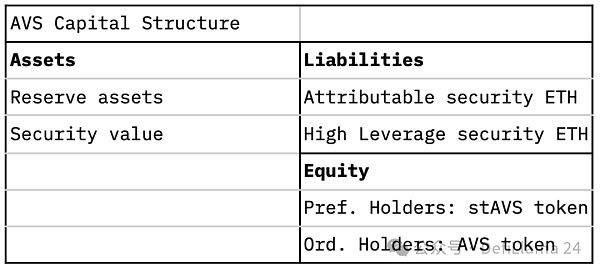

The re-staking economy adds a new dimension to the capital structure. AVS that leases cryptoeconomic security from ETH re-stakers will have quasi-debt/equity characteristics. In the context of a theoretical AVS balance sheet, the hybrid nature of re-staking comes from the fact that re-staking rewards will sometimes be paid in ETH, sometimes in the native token of AVS, or a mix of both. If re-staking earns returns in ETH, they will be more like a “debt investor” in AVS; re-staking earns do not explicitly benefit from the upside potential of the AVS economy. If re-staking earns returns in the native token of AVS, they will be more like an “equity investor” in AVS. In addition, there is also a concept of “priority” and the perceived security of re-staking ETH based on how many times ETH is re-staking. This depends on how many times ETH is re-staking. The probability of “default” of re-staking ETH can increase exponentially with the number of times the same ETH is re-staking to secure another AVS. In the most favorable case, the “attributable security” that is exclusively retained by AVS and paid for with ETH re-staking returns can be considered “senior debt”. As ETH is re-staking more times in various AVS, ETH will be considered “junior debt”.

If ETH re-stakers in AVS are rewarded in ETH, their total return is simply the re-staking yield. In other words, re-stakers have no direct exposure to the upside potential of the AVS economy. If ETH re-stakers are rewarded in AVS's native token, their total return will include a price return component for the AVS token. Therefore, re-stakers care about the upside potential of the AVS economy to the extent they hold issuance.

Total Return = ETH Price Return + ETH Staking Yield + Re-Staking Yield

Where

Re-Staking Yield = Re-Staking Yield (Non-Volatile % + AVS Token % x AVS Token Price Return)

Trust Cost of a Single AVS: The above tells us that the return required by a re-stakeholder, and therefore the “trust cost” of the AVS network, depends on three main factors:

• The number of times ETH supplied to AVS has been re-staked (i.e., the less ETH has been re-staked = lower trust cost)

• The currency in which re-stakeholders receive re-staking rewards (i.e., native token = higher trust cost)

• AVS token price returns, which will reflect business fundamentals in the long run

It follows that re-stakers who receive re-staking rewards in the native token of AVS will need to carefully consider the long-term sustainability of the network. The chart above shows the price return breakdown for Ethereum. We can imagine that similar exercises can be conducted on a forward-looking basis for the AVSs they will re-stake based on their perception of the business viability of the AVS.

Trust costs in multiple AVSs: The role of the AVS operator or LRT is to aggregate the total value locked (TVL) from re-stakers to re-stake in multiple different AVSs to increase the returns on re-staking ETH. We are unable to quantify the correlation between different AVSs and the increased likelihood of slashing losses. Nonetheless, we acknowledge that the expected loss from a single slashing event will increase as ETH is re-staked multiple times in various AVSs.

Trust Return Formula: Given the above, we arrive at a simple intuition about the “trust return” in the re-staking economy. That is:

Trust Return = ETH Price Return + ETH Staking Return + Re-staking Return - Default Loss

What should the restaking return of an AVS be?

Currently, there is no historical record, nor any notion of how much of a security budget a re-staking AVS can afford as ETH collateral. We propose a simplified framework for assessing what a hypothetical AVS, if it were considered a business, might afford, taking into account constraints such as the return that its token holders might demand.

In short, the degree of security that an AVS promises to provide for its business should be proportional to the amount of value or activity performed on the AVS. Under-committing could disrupt AVS or undermine its operations. Over-committing runs the risk of incurring unaffordable fees without additional marginal benefit to AVS users.

Leveraged Work Yield (Re-staking)

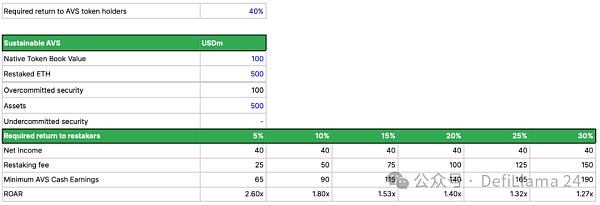

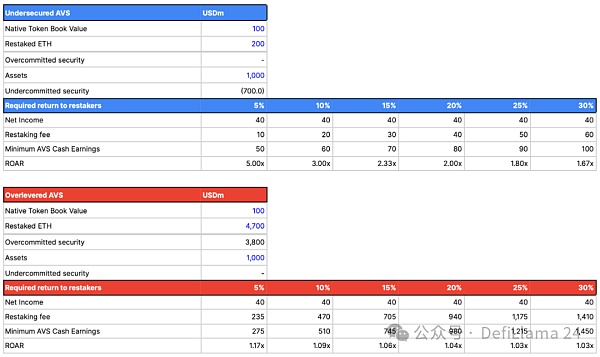

This is a schematic, simplified representation of what the AVS balance sheet needs to look like, and the minimum levels that AVS cash earnings need to reach on an annual basis to achieve different required rates of return (i.e., re-staking fees or yields) for re-stakers. We also show the corresponding ROAR ratios to signal sustainability, and compare to a case where AVS does not have enough security to run its service, and a case where it has too much security to afford.

To clarify what to expect from these reverse-engineered revenue thresholds: To date, only a handful of projects on Ethereum have generated over $100 million in revenue per year, including Ethereum itself.

Today, EigenLayer and higher-leveraged derivatives (like Liquid Restake Protocols) use the concept of credits to attract initial capital to commit their collateral for re-hypothecation. This is a smart move because it avoids early commitment token dilution and allows these protocols to change the value assessment criteria of credits in terms of actual dilution or hard currency payments. With enough bargaining power gained through higher committed capital, they can decide not to assign any monetary value at all, achieving a 0 basis cost of capital.

Prior to this, the market was pricing in an expected return on credits in the range of about 40%. Using our earlier framework, this suggests that in order for ROAR to be safely greater than 1, an AVS should be able to generate an equity return equivalent to at least 40% of its native token. For low-margin crypto services, especially if asset efficiency is less than 100%, i.e., underutilized TVL to set aside loss reserves, the only path forward for the service operator is through a more leveraged balance sheet.

Who are the customers of AVS?

Many AVS can be viewed as providing value-added services to other infrastructure providers such as Rollups. In this sense, AVS can be viewed as B2B (business-to-business) services rather than B2C (business-to-consumer) services.

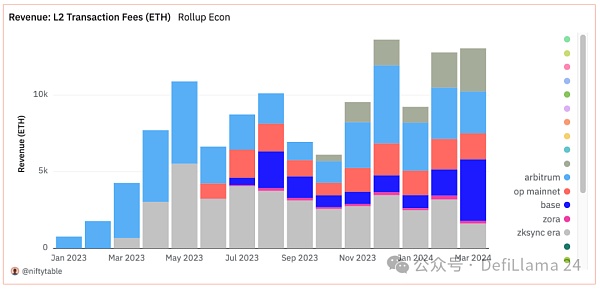

The market potential of AVS that provide services for Rollups today will be limited by the revenues from Rollups. The 12.8k ETH Gas fees generated by the top Ethereum L2 in February means a run rate of 153.6k ETH in Rollups revenue. Let's assume that all Rollups revenue can be redistributed to AVS services. Currently, Eigenlayer has 3.535M re-staked ETH. This means that in the most generous scenario where all L2 revenue can be redirected to AVS, re-stakers will receive an annualized return of 153.6k/3.535m = 4.3%. We note that this annualized return does not take into account any consideration of haircut risk and "default losses", which we will explain in the next section.

Source: Dune. (@niftytable),https://tinyurl.com/2dbs87do

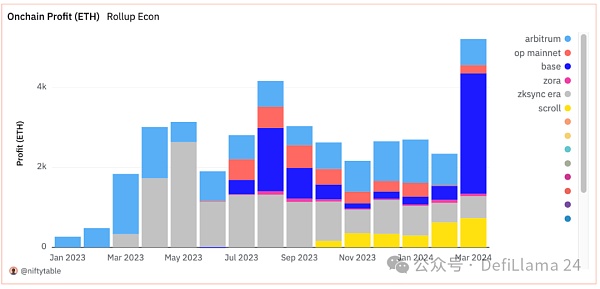

If we limit the market opportunity to sequencer profits (i.e. Rollups revenue minus Ethereum call data costs), then the number shrinks to 54k/3.535m = 1.5% annualized return.

Source: Dune. (@niftytable),https://tinyurl.com/2dbs87do

In reality, our suspicion is that most Rollups will do their best to protect their sequencer profits and choose to provide services that save costs (e.g., EigenDA provides cheaper data availability than Ethereum) or solve real technical gaps (e.g., interoperability). Therefore, in the early stages of AVS's launch, it may be necessary to pay most of the staking income as the native token issuance of AVS. As we mentioned in the trust cost formula we derived above, paying in native token issuance rather than ETH will increase the trust cost of AVS.

Interesting changes in market dynamics are likely as the +40% market expectation (reflected via credits) of re-staking APY contends with the realities of AVS monolith economics and scale. This expectation is even more challenging when compared to the lower share of profits that L2s are likely to offer from re-staking gains. Assuming all layer 2 profits go to re-stakers to pay for shared security — which is an impossible upper bound estimate at best — we’re left with roughly 1.5%±0.5% re-staking yield. If that profit share were to go to a more reasonable but still aggressive level of 20% of all layer 2 profits going to re-stakers, we’d be looking at a yield of about 10%. That’s a re-staking yield of 0.75%±0.25%. This is at least in line with one estimate from Emerging Liquid Re-staking Tokens (from Jason Vranek of Puffer Finance), which recently estimated that a re-staking yield of about 0.5% would be “good.”

Default Losses: Slashing and Other Risks

The risks of re-staking must be considered carefully, as user collateral is effectively re-staking to support multiple primary validation services. This means that re-stakers’ collateral has the potential to be slashed under entirely new conditions, depending on a host of idiosyncratic factors outside of cryptoeconomic validation activity.

EigenLayer’s risk document confirms very clearly and convincingly that it will not re-stake staked tokens. However, there is a concept of leverage as tokens are reused multiple times, perhaps more akin to leverage in the sense of a bank multiplier.

The risk of re-staking ETH starts with slashing or operational risk of staked ETH. In earnings management research conducted for Lido DAO, we found that large slashing risk (a single operator offline for more than 7 days) would impact all stETH by about 0.01%. Operational risk is more devastating in tail risk events, such as the Prysm bug and large withdrawal queues (0.315%).

These risks are compounded with re-staking risk. When re-stakers pledge their ETH to secure AVS, the ETH is “at risk” in a manner similar to Ethereum staking. Node operators who are entrusted to perform validation activities must operate correctly to avoid slashing of user collateral. There is no final version of the slashing conditions that will affect re-stakers, so we can only guess how likely this is. The priority is to keep operations simple and easy to implement, and not change node requirements to prevent high corruption costs.

We believe these risks are not entirely impossible. Underwriting an AVS will likely prove to be very similar to the credit of underwriting a normal commercial loan, with the capital now at risk being influenced to some extent by operational and commercial risk, rather than just pure consensus algorithm math. It is also worth mentioning that there are moral hazard effects as well, as AVS that cannot afford a local L1 to underwrite their activities will be incentivized to seek lease capital at a lower cost, similar to the moral hazard of insurance underwriting.

We can qualitatively frame the impact of losses, including haircuts, as default losses, similar to traditional finance analogies. Default loss captures the additional risk that ETH holders opt in to:

• For non-stakers, Default loss is 0

• For native stakers, Default loss is determined by Slashing Probability * Slashing Loss Rate plus additional idiosyncratic risk, depending on the chosen staking method

• For re-stakers, Default loss includes the previous, with the addition of the re-staking service’s portfolio Default loss: Some text

○ Idiosyncratic losses from slashing or other operational errors

○ Correlated losses between a slashing or loss event on one AVS and another

○ Correlated losses between Ethereum staking and AVS

That said, we can only guess at what the sources of loss from re-staking are.

This means that default losses actually increase the more times ETH collateral is re-staking. The more opportunities for correlation to occur, the more likely a loss-of-gain event will occur.

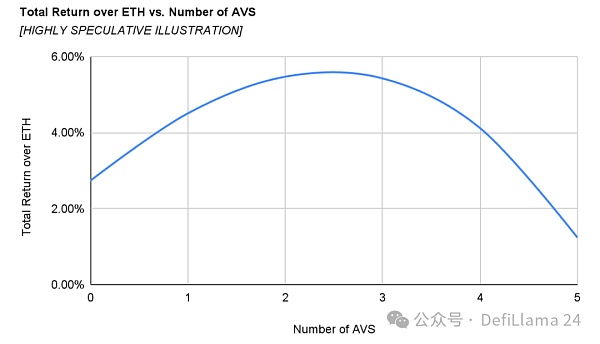

That said, there are various mitigations that can mitigate potential loss outcomes that could result from slashing or operational errors. The maximum loss for stakers on Ethereum is essentially capped at 50% of each validator’s collateral. Similarly, we can expect that there will be an upper bound on the correlation between AVS and between AVS activity and Ethereum staking. We expect that the final optimized curve for AVS selection will produce diminishing returns due to default losses, so that there may be an optimal maximum number of AVS to allocate.

The curves below assume that every AVS in the set is identical and that the average re-staking fee is approximately 5%, which is the maximum estimated upper bound on what Rollups revenue could generate.

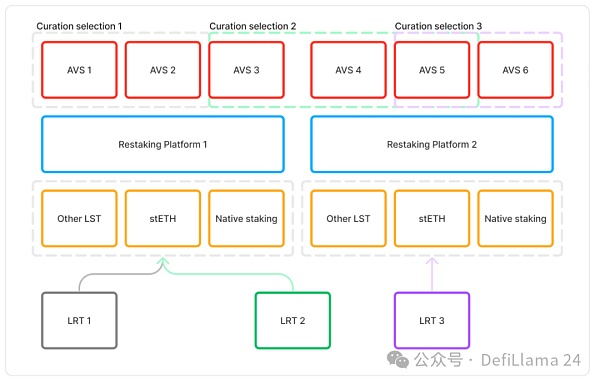

Liquidity Re-staking Protocol

The Liquidity Re-staking Protocol (LRT) introduces a new dimension of aggregation and liquidity. Unlike Liquid Staking Tokens (LSTs) staked on Ethereum, LRTs’ asset allocation strategies involve more diverse risks and rewards when considering their balance sheets. While management of node operators is a key function of LSTs, they largely converge on similar dimensions and compete fiercely on price and performance.

LRT as an evolution of LST may find that the final product does not match the user's expectations of the underlying assets. When mapped to the familiar fiat financial system, LST plays the role of a monetary policy transmission tool, similar to core bank deposits or government debt instruments. Where stETH is the underlying asset, LRT is fund management, that is, more similar to a structured product or bond fund.

The so-called benefit brought by LRT lies in AVS management, that is, maximizing the return of re-pledged ETH by generating AVS re-pledge fees while minimizing default losses. Improvements in this decision space must be operated in a limited profit space to be shared among more participants.

If the returns are insufficient, there will be no meaningful differentiation, and LRT may be forced to take on more risk by allocating to AVS with higher balance sheet leverage, or simply fail gracefully or default to competing with LST.

Appendix: Work Yield

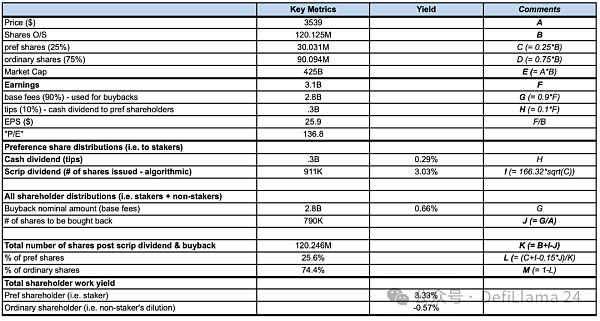

We use hypothetical numbers and a familiar equity analogy to illustrate Ethereum's concept of "work yield". Ethereum's "capital return policy" for its token holders is set as follows:

Stakers are preferred shareholders and are entitled to cash dividends (i.e. user tips and MEV) + stock dividends (i.e. new token issuance). These two make up the total validator reward.

Non-stakers are ordinary shareholders.

All shareholders can benefit from stock buybacks (i.e. user gas burning).

As shown below, stakers receive a higher yield at the expense of non-stakers. Specifically:

Stakers receive a 3.33% work yield, made up of a 0.29% cash dividend yield and a 3.03% “stock dividend” yield.

Non-stakers receive a -0.57% work yield, which is caused by dilution from “stock dividends” (i.e. new token issuance) issued to stakers.

In summary, cryptocurrencies provide a uniform price return to all token holders, but provide different levels of “work yield” depending on the type of token holder. This means that people who provide work may have a different view of the “fair value” of the token than those who do not provide work.

Overview of the Work Yield Model, April 2, 2024, reference: https://dune.com/steakhouse/eth-decomposition

Tether CEO Paolo Ardoino said in an interview. “Launching your own blockchain is probably not the right move. There are many very good blockchains.”

JinseFinance

JinseFinanceEU Member States, Norway, Liechtenstein and the European Commission have launched a publicly accessible blockchain.

Others

OthersThe law on promotions is set to come into effect around four months from now if there are no objections, the finance ministry has said.

Coindesk

CoindeskSome analysts feel that Binance’s relationship with its own token seems somewhat suspicious.

Beincrypto

BeincryptoMYEG’s Zetrix blockchain and Mimos blockchain will be the components of the Malaysia Blockchain Infrastructure (MBI).

Others

OthersDigiDaigaku not only has actual game functions (not launched), but is also funded by well-known individuals and venture capital companies, such as Paradigm, FTX, Coinbase, etc. The project party is a Web3 game development company called Limit Break, which was founded by a group of Web2 senior teams who have been in the field of mobile games for many years.

Nell

Nell Cointelegraph

CointelegraphAs self-custody puts a lot of responsibility on a user, many may find it way too uncomfortable or too hard to handle.

Cointelegraph

CointelegraphThe government is hoping to make Barcelona a digital hub by offering various skills programs to university students and boot camps to cultivate talent.

Cointelegraph

CointelegraphThe U.S. defense technology company has started the exploration of the metaverse, applying the metaverse to military simulation exercises.

Ftftx

Ftftx