Chile is one of the most economically stable and financially mature countries in Latin America, and plays a significant role in the current crypto market. While its overall trading volume is smaller than that of regions like Brazil and Argentina, its market activity remains remarkable. According to the latest industry report, Chile's annual cryptocurrency trading volume in 2024 was approximately US$2.38 billion, ranking among the top in Latin America. In terms of user acceptance, Chile also performs exceptionally well, with a cryptocurrency holding rate of approximately 13.4%, ranking among the highest globally. It is worth noting that as the Chilean crypto market becomes increasingly active, Chilean financial regulators are also following this trend, viewing crypto assets as an important component of driving financial innovation. On January 4, 2023, Chile's "Financial Technology Law" (Ley Fintech, Law No. 21, 521) was officially published in the official gazette, considered one of the most important reforms to Chile's capital market in the past decade. The law aims to promote competition and financial inclusion in the financial system through technological innovation, establishing clear regulatory boundaries for unregulated fintech services, including crowdfunding platforms, alternative trading systems, credit, investment advisory, and custody of financial instruments. Subsequently, on January 12, 2024, General Rule No. 502 (NCG 502) further clarified the registration, authorization, corporate governance, risk management, capital, and collateral requirements for financial service projects (including platforms that actually handle crypto assets). Regarding crypto assets, while Chilean authorities currently maintain a cautious regulatory approach, considering virtual currencies neither legal tender nor foreign currency, their recognition of crypto assets as "intangible assets" has led the Chilean Financial Market Commission (Comisión para el Mercado Financiero, CMF) to include them in the "custody of financial instruments" service category in the Financial Technology Law (Law No. 21. 521, 2023), thus providing stable and predictable behavioral guidelines for market participants. As the Chilean crypto market continues to expand and regulations are constantly updated, it is necessary to systematically understand the latest regulations for crypto assets in Chile, to understand the tax compliance framework of the Chilean Tax Service (Servicio de Impuestos Internos, SII), and the latest regulatory system implemented by the CMF based on the Fintech Law.

1. Chile's Basic Tax System

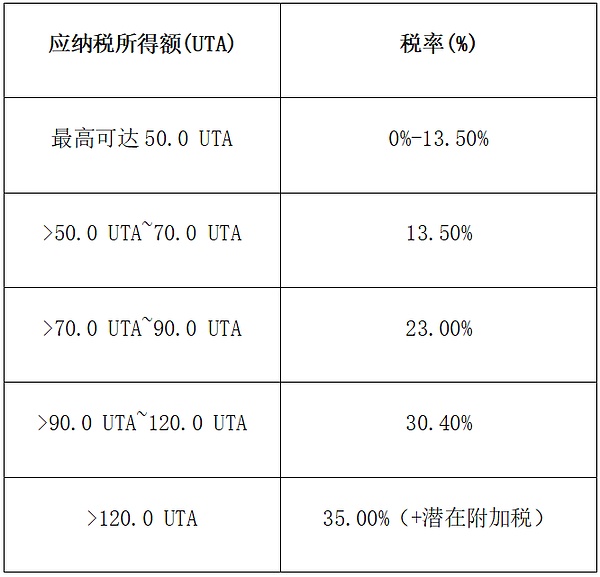

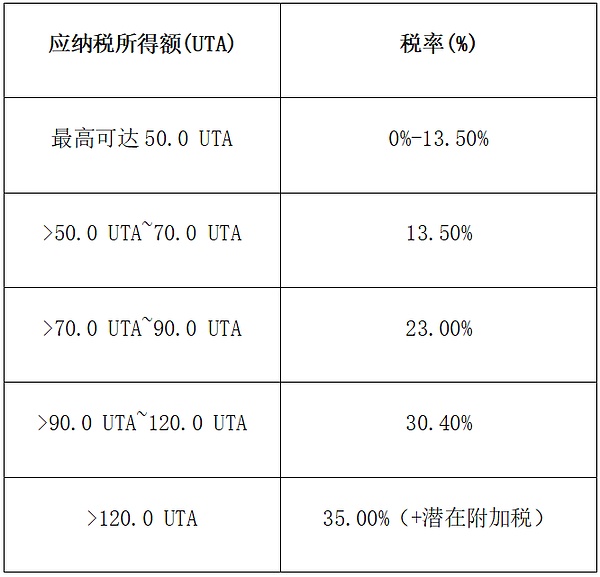

SII implements tax supervision on proceeds from cryptocurrency transactions in accordance with existing regulations such as the Income Tax Law (Ley sobre Impuesto a la Renta) and the Sales and Service Tax Law (Ley sobre Impuesto a las Ventas y Servicios). Chile's tax system is based on three core tax categories: the First Category Tax (Impuesto de Primera Categoría, corporate income tax), the Supplemental Global Complementario / Impuesto Adicional (for resident/non-resident personal income), and the Value Added Tax (Impuesto al Valor Agregado, IVA). 1.1 The First Category Tax (Corporate Income Tax) The First Category Tax is a core component of Chile's corporate income tax system, primarily applicable to companies engaged in industrial, commercial, mining, agricultural, financial, and other economic activities in Chile. This tax was originally established by the Income Tax Law (Ley sobre Impuesto a la Renta, Decreto Ley NO. 824), and it is levied on an accrual basis, meaning that taxable income is recognized during the accounting period in which revenue is realized or expenses are incurred. It is important to note that the Chilean companies defined in this law, in principle, include both local companies and foreign companies with a permanent establishment in Chile, both of which are subject to corporate income tax. The standard corporate income tax rate is 27%. This rate applies to most general businesses, especially large or multinational corporations. However, to support economic recovery and the sustainable development of SMEs, the Chilean Ministry of Finance (Ministerio de Hacienda, MH) has introduced temporary tax incentives starting in fiscal year 2025. According to Law No. 21.755 on Simplifying Regulation and Promoting Economic Activity, corporate entities meeting Chilean SME standards will have their income tax rate temporarily reduced to 12.5% in fiscal years 2025, 2026, and 2027; it will only revert to 15% in fiscal year 2028. 1.2 Supplementary Global Tax/Surcharge (Resident/Non-Resident Personal Income Tax) Chile's personal income tax system consists of two complementary taxes: the global supplementary tax and the surcharge. The former applies to tax residents (i.e., natural persons residing in Chile for more than 183 days or having a center of residence) and taxes their global income; the latter applies to non-resident individuals and taxes only their income derived from within Chile. The global supplementary tax employs a progressive tax rate system (impuesto progresivo), with rates ranging from 0% to 40%, and the specific tax bracket determined based on the annual tax unit (Unidad Tributaria Anual, UTA). The SII adjusts the UTA value annually based on inflation and exchange rate factors. The personal income tax brackets for 2025 are as follows:

1.3 Value Added Tax

Chile's Value Added Tax (Impuesto al Valor Agregado, IVA) was established by the Sales and Service Tax Law (Decreto Ley NO.825, 1974) and is collected and managed by the tax authorities. The standard tax rate is 19%. IVA applies to the sale of goods, provision of services, and importation within the country. Taxpayers must register before providing taxable transactions, and there is no minimum turnover threshold. This system employs a deduction mechanism of output tax minus input tax to avoid double taxation, and is typically declared and paid monthly. According to Chile's Sales and Service Tax Law, the scope of VAT includes: 1) sales of movable or partially immovable property for consideration; 2) various services provided for remuneration; and 3) goods imported into Chile. This means that whether it's a domestic transaction or a cross-border import, VAT must be paid if the above conditions are met. Exported goods and certain services (education, healthcare, finance) enjoy zero tax rates or are exempt from taxation, while low-value imports, used car sales, and international transportation are subject to a simplified collection system. It is worth noting that since 2020, non-resident digital service providers offering online services to Chilean consumers are also required to register and pay IVA. Whether IVA also applies will be discussed in the next section.

2 Tax Treatment of Crypto Assets

Through multiple administrative rulings and frequently asked questions, the SII has positioned crypto assets as intangible/digital assets, explicitly stating that they are neither legal tender nor foreign exchange. Furthermore, the income generated from crypto assets is included in the scope of taxation of general income under the Income Tax Act (i.e., listed as "Other General Income" as shown in Art. 20 No. 5). This determines the applicability of three types of taxes, including the first type of tax (corporate income tax), supplementary global tax or surcharges, and the treatment of value-added tax, which should be based on this intangible asset classification. 2.1 Type I Tax SII clarifies that "mayor valor/capital gain" generated from the buying and selling of crypto assets should be classified as general income under Article 20, Paragraph 5 of the Income Tax Act, thus affecting the calculation of Type I tax (for corporations) and final individual tax (IGC/IA). For corporations, operating income recognized by accounting or tax regulations is included in their taxable profits; for individuals, the corresponding final tax burden applies based on their tax resident/non-resident status. 2.1.1 Sale/Transfer (including "currency exchange" and currency purchase of goods/services) Sale (i.e., conversion to legal tender): The consideration for the sale is confirmed at the time of sale (calculated at the fair value of the Chilean peso on the date of sale). Taxable income = consideration for sale - purchase cost. SII requires documentation such as transfer vouchers or invoices to prove the existence of costs and transaction records. Currency exchange/currency exchange for goods or services (considered barter/transfer): The official Q&A does not provide specific details on this. However, SII treats the disposal of general crypto assets as a transfer, and the gains should be calculated based on the transaction price on the day of purchase, for use in tax declaration and payment. Therefore, some scholars believe that this principle applies not only to the sale of cryptocurrency for fiat currency but also to cryptocurrency swaps or payments for goods or services using cryptocurrency; that is, any outflow of crypto assets may trigger capital gains tax. 2.1.2 Mining/Staking/Airdrop Mining: Mining proceeds should be recognized as the book value of the asset on the day of acquisition at the market price of that day. Direct costs incurred in mining (such as electricity, hardware depreciation, etc.) can be deducted at the legal/individual level (depending on whether it is a business activity) according to relevant rules or calculated as costs. Staking/Airdrop: SII has not made a clear statement. Some scholars believe that the acquisition cost of tokens obtained for free through staking or airdrop can be recorded as zero. When selling them later, the taxable income should be calculated by subtracting this (zero) cost from the sale price. If the tokens are obtained for business purposes, they should be handled separately in accordance with accounting and tax rules. 2.1.3 Transaction Fees/Brokerage Commissions SII recognizes that, when determining taxable income, commissions received by brokers/exchanges can generally be recorded as "necessary expenses for generating such income" in the current period (i.e., as operating expenses or deductible expenses), but cannot be directly capitalized as asset costs (i.e., fees are not considered "tax costs" of the crypto asset, but rather expense treatment), depending on the specific accounting and tax rules applicable to the taxpayer. 2.2 Supplemental Global Tax/Surcharges For resident individuals, income from crypto asset transactions is typically included in annual consolidated income and levied by a supplemental global tax at progressive rates. The SII states that if the crypto asset transaction is undertaken by a natural person and is not commercially funded, the income should be taxed according to general income tax rules, including the difference between the transfer price and the purchase cost. For non-resident taxpayers, income from crypto asset transactions occurring in or originating in Chile is, in principle, subject to a surcharge, but no specific ruling in publicly available literature clarifies the detailed taxation method. Therefore, in practice, non-resident related income should still be presumed to be subject to a surcharge based on the tax law framework. 2.3 Value Added Tax (IVA) According to the SII ruling, crypto assets, lacking physical form, are not subject to the taxation of tangible goods sales under the Sales and Service Tax Act, and therefore are generally not subject to the 19% IVA. Furthermore, regarding intermediary services or commission fees provided by exchanges or platforms, the SII notes in its FAQ that these services "may be subject to IVA" and require corresponding invoices or vouchers.

3 Chilean Cryptocurrency Regulatory Framework and Future Trends

To gain a more comprehensive understanding of the position of tax policy in Chile's cryptocurrency regulatory system, this section will review the formation and evolution of the regulatory framework from an institutional perspective, focusing on its basic structure, main rules, and latest revisions.

3.1 Early Regulatory Framework

Between 2018 and 2020, Chilean regulatory authorities gradually explored the regulatory framework for cryptocurrencies. The regulatory characteristics during this period were generally rudimentary, mainly focusing on the legal characterization and tax treatment guidelines for cryptocurrencies.

In 2018, the SII issued its first authoritative response regarding the tax characterization of crypto assets in Ordinary Letter No. 963/2018, declaring that income derived from the buying and selling of crypto assets falls under the category of general income as defined in the Income Tax Act (Art. 20 Nº5), and thus clarifying the framework for income tax application (distinguishing between individuals and corporations, etc.). This ruling laid the foundation for subsequent tax practices (such as cost recognition and the treatment of frequent transactions). Subsequently, in 2020, SII further issued General Letter No. 1474 (2020) providing more detailed administrative guidance on cost calculation methods, fee deductions, and high-frequency trading scenarios, addressing numerous practical issues in daily transactions and tax reporting (such as accounting recognition and cost methods). 3.2 Current Regulatory Framework As mentioned above, Chile's systematic regulation of crypto assets began with the Fintech Law of 2023; therefore, the Chilean authorities' current regulatory framework for crypto assets is based on this law. At the regulatory enforcement level, the CMF (Common Financial Services Fund) takes the lead, responsible for developing general rules and implementing registration and authorization procedures for the financial service categories listed in the Fintech Act (such as alternative trading systems, financial instrument custody, and financial instrument intermediaries). CMF's General Rule No. 502 details the registration, authorization, governance, risk management, and capital requirements for financial service providers (financial service providers/virtual asset service providers), thus transforming the abstract requirements of the Fintech Act into enforceable compliance thresholds. Concurrently, the Tax Compliance Act of 2024 (Ley No. 21.713) strengthens the powers of Securities Institutional Providers (SIIs) in valuation, data acquisition, and anti-tax avoidance, emphasizing the ability to scrutinize complex transactions and non-market pricing, thereby indirectly increasing the tax compliance risks of crypto-asset-related transactions. The Central Bank of Chile (Banco Central de Chile, BCCh) has exclusive functions in monetary policy, payment systems, and determining the status of legal tender. It also coordinates and conducts policy research with the Central Bank of Chile (CMF) on issues such as "payment-type digital assets" (e.g., stablecoins or retail central bank digital currencies). The division of labor between BCCh and CMF is as follows: CMF focuses on regulatory compliance in capital markets and financial services; BCCh focuses on publicly traded payment methods and financial stability risks. They maintain policy cooperation on issues with overlapping boundaries. Taxation and anti-money laundering/counter-terrorist financing and cross-border intelligence tasks are undertaken by the SII and the Chilean Financial Intelligence Agency (Unidad de Análisis Financiero, UAF). SII provides guidance on the tax characterization and practical treatment of crypto assets (such as treating crypto assets as intangible assets, income tax treatment of transfer events, and tax treatment of transaction fees) through a series of official documents and Q&As, while UAF is responsible for reporting suspicious transactions related to anti-money laundering/counter-terrorist financing and cross-border intelligence, as well as inter-agency collaboration. Overall, under the macro-guidance of the Fintech Law, the Chilean regulatory framework presents a governance structure of "three powers working together, each performing its own duties": (1) CMF is responsible for market access, governance, and ongoing supervision; (2) BCCh handles currency/payment stability issues; (3) SII and UAF are responsible for tax and anti-money laundering compliance, respectively. This multi-agency collaborative governance model aims to achieve a balance between encouraging financial innovation and ensuring market integrity. 3.3 Current Key Rules Chile places the core regulatory rules for fintech and crypto-related services under the Fintech Law and its General Rule No. 502, developed by the CMF. The former defines the categories of regulated financial services and regulatory objectives, while the latter puts registration, authorization, governance, and ongoing compliance requirements into practice. These rules can be summarized into four categories. The first category, and the most significant compliance hurdle, is registration and market access. Anyone providing financial services specified in the Fintech Act (including alternative trading systems, financial instrument custody, and financial instrument intermediation) must register with the CMF and obtain authorization. Registration applications must include documents on corporate governance, management team qualifications, business model, capital structure, and risk management. Foreign entities may apply for entry if they meet certain conditions. This system aims to bring off-exchange or unregulated activities under regulatory oversight, improving market transparency from the outset. The second category of requirements focuses on corporate governance, capital, and operational capabilities. General Rule No. 502 sets clear standards for governance independence, client asset segregation, business continuity plans, and minimum capital or collateral, and requires a third-party opinion report on operational capabilities as part of the review process. The regulator emphasizes using these requirements to reduce systemic risks associated with custody and trust services, while simultaneously establishing a baseline for investor protection. The third category of rules concerns anti-money laundering/counter-terrorist financing and disclosure obligations. Chile's UAF has clear requirements for reporting suspicious transactions, customer due diligence, and real-name registration. Virtual asset service providers and other regulated financial service providers must conduct transaction monitoring and report suspicious activities according to UAF and CMF standards. Meanwhile, SII tax guidelines require the maintenance of complete transaction records and valuation documents to facilitate tax compliance checks. Finally, regulators emphasize ongoing monitoring and enforcement consequences. The CMF maintains the deterrent effect of its rules through routine reviews, information requirements, and administrative sanctions (including fines and deregistration) against non-compliant entities. At the same time, the 2024 tax reform enhanced SII's investigative powers in valuation and anti-tax avoidance, meaning that in areas where tax and regulation overlap (such as large off-exchange transactions involving related parties), they will face stricter compliance and audit risks. In response, companies need to prioritize compliance governance, valuation methods, and tax due diligence. 3.4 Latest Revisions and Future Focus Since 2024, the pace of rule revisions has accelerated significantly. In December 2024, the CMF revised General Rule No. 502, refining the registration and authorization procedures and the supporting documentation required for applications. This improved the efficiency of regulatory review and reduced the scope for interpretation in practice (for example, clarifying the positioning and submission requirements for third-party operational capability opinions). Simultaneously, the Tax Compliance Act passed in 2024 significantly enhanced the powers of Subsidiaries in valuation, information collection, and anti-tax avoidance, meaning that the intensity and complexity of tax audits will increase regarding issues such as large off-exchange transactions, related-party transfers, and valuation adjustments under extreme price fluctuations. The regulation of "payment-oriented" digital assets (especially stablecoins) and central bank digital currencies (CBDCs) has become a core focus of regulation in the next phase. The Financial Action Task Force (FATF) has conducted proof-of-concept and pilot programs for CBDCs and has proposed a special study on the regulation of stablecoins as a means of payment. Both practitioners and regulators are preparing to include tokens with strong payment functions within the scope of currency/payment regulation, and this type of regulation is likely to be jointly promoted by the FATF and the Central Bank Financial Regulatory Commission (CMF). Therefore, for tokens issued or operated for payment purposes, issuers and virtual asset service providers offering related services need to assess potential licensing, capital, and liquidity requirements in advance. Regarding anti-money laundering/counter-terrorist financing and cross-border intelligence cooperation, the Financial Action Task Force's guidelines on virtual assets and virtual asset service providers continue to serve as international compliance benchmarks. Chilean regulators have clearly aligned their design of registration, due diligence, and reporting obligations with the Financial Action Task Force's (FATF) risk-based methodology. Therefore, virtual asset service providers (VASPs) should expedite technical and procedural integration in customer identification, transaction information transmission, and cross-border cooperation to avoid compliance gaps in cross-border transactions. In summary, the future focus of Chilean cryptocurrency regulation can be broadly summarized in three aspects: First, regarding valuation and tax auditing, the SII is expected to strengthen the review of high-risk transactions and gradually promote the unification of valuation and reporting standards; second, the regulatory positioning of payment tokens will become clearer, especially with potentially stricter rules for stablecoins and central bank digital currencies (CBDCs), raising the bar for issuance and use; finally, international compliance cooperation and technological integration will become a trend, requiring VASPs to gradually implement transaction information reporting and "travel rules" requirements that comply with FATF and international standards. For market participants, the practical implications are mainly threefold: 1. Establish a more stringent valuation mechanism and a complete transaction documentation retention system; 2. When dealing with payment or exchange scenarios, make advance plans for liquidity and capital; 3. Optimize the technical architecture to support cross-border information exchange and compliant reporting, reducing potential operational and regulatory risks. 4. Conclusion With the rapid expansion of the Chilean cryptocurrency market, the country has established a comprehensive and transparent regulatory system for crypto assets through tax rulings, legislation, and supporting regulatory measures. From a tax perspective, the SII has clearly defined the nature and transaction processing of crypto assets, providing tax guidance for corporate and individual investors. From a regulatory perspective, the CMF and anti-money laundering and terrorist financing units have formed an interconnected regulatory mechanism, making the compliance framework more systematic and operational. The establishment of this system has given Chile significant institutional competitiveness within the region. On the one hand, clear rules and regulatory pathways enhance market predictability and legal security; on the other hand, tiered regulation and a gradual implementation mechanism provide appropriate flexibility for various fintech companies, balancing innovation and risk control. Looking ahead, with the gradual implementation of international reporting standards, the Chilean market is expected to further align with global regulatory standards, attracting more institutional investors and compliant projects to the local market. For investors, Chile has become one of the few crypto asset investment destinations in Latin America that simultaneously offers institutional transparency, clear compliance pathways, and policy continuity, and its regulatory evolution will continue to set a benchmark for regional financial innovation.

Weatherly

Weatherly