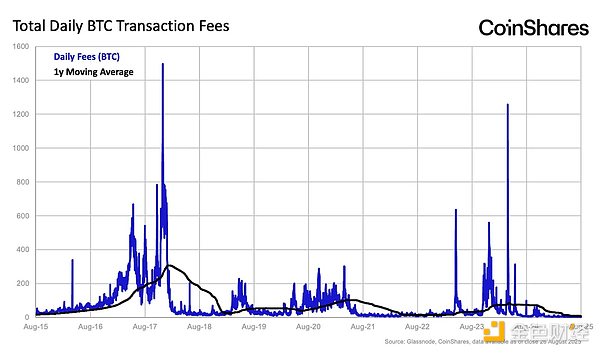

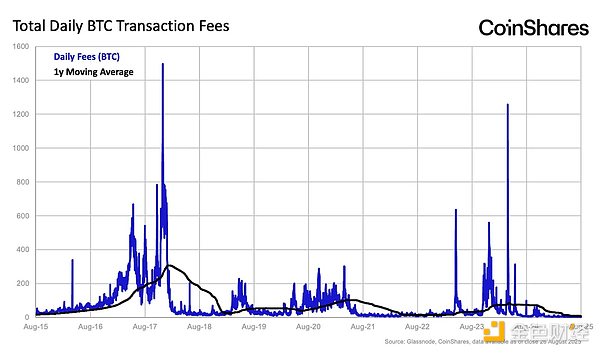

Because the future purchasing power of tokens is unpredictable, no amount of monetary policy changes can guarantee the full security of the blockchain—instead, they weaken the token's monetary properties and risk a security death spiral, as the token fails to compete for monetary demand and mining/validation rewards lack sufficient value to ensure the blockchain's security. In short, tail issuance is not and cannot be a guarantee of sustainable settlement security. On the contrary, I believe that constantly modifying the protocol's monetary policy poses a far greater risk to long-term security than simply letting the market tell us whether it wants something. A few weeks ago, on August 12, 2025, the Proof-of-Work (PoW) blockchain Monero underwent a six-block reorganization. In the days that followed, it underwent several more nine-block reorganizations. While this only represents a 12-18 minute rewrite of history, given Monero's 2-minute block time target (roughly equivalent to 2 Bitcoin blocks), it's still far beyond the standard, non-malicious reorganizations that occasionally occur on PoW blockchains. Statistically, natural reorganizations exceeding 2 minutes are extremely unlikely, and their probability decreases exponentially with each block. Therefore, the 6-block reorganization was likely an intentional act by Qubic—a peculiar blockchain that effectively acts as a Monero mining pool, a fact they have publicly acknowledged. While the media widely characterized the attack as a 51% attack, deeper analysis has uncovered no convincing evidence to support this claim. These reorganizations are most likely manifestations of "selfish mining," a time-honored strategy used by miners controlling approximately 33% of the hashing power in PoW blockchains to maximize mining profits. Proof-of-stake blockchains are also susceptible to this type of attack, and even at low levels of total stake, the complexity of PoS makes analysis difficult. However, this post is not about selfish mining or Qubic's unique incentive mechanism, which exploits token markets to (at least temporarily) boost the profitability of Monero miners, who then direct their hashing power toward Qubic, rapidly increasing their hashing power. Instead, I want to discuss a less obvious, but in my opinion more important, lesson: tail issuance is not a viable solution for the long-term protocol security of a blockchain, and we must resist the urge to tweak Bitcoin's monetary properties in the name of long-term security. Let's First Agree on Some Definitions One reason the discussion of this topic (and, frankly, most other debates) is so tedious is that people can't agree on the meaning of certain words and terms, leaving everyone saying their own thing. To avoid this, I want to be very clear about what I mean when I mention certain words and terms. Protocol Security — Few terms are thrown around as loosely as this one. It's often simplified to "attack costs," a vague and unspecified reference to reorganization costs. When we use this term, we're strictly adhering to the meaning of settlement guarantees, as detailed by Nic Carter in 2019. Censorship Resistance — The ability of a blockchain to expel malicious miners who reach 51% or more of the hashrate and use that power to censor blocks. Tail Inflation — The use of unlimited inflation as an incentive for block creation. Security budget—I try to avoid using this term because it can't be meaningfully quantified within the context of blockchain protocols. Therefore, it's purely conceptual and has no concrete meaning. Bitcoin's long-term security appears to be in question. Let me briefly summarize the obvious problem behind all of this, which stems from Bitcoin. A key assumption of Bitcoin is that transaction fees will become the primary source of revenue for miners once the supply of new coins is exhausted. Technically, this is already the case. Over the past year, if you average out the current block reward of 3.125 BTC, you're left with approximately 0.06 BTC in transaction fees (even less if you average it over 30 days). The problem is obvious: transaction fees currently represent less than one percent of the block reward, which is not very significant. In fact, if Bitcoin-denominated fees stop increasing from now on, they won't match the size of the block reward until after six halvings, which is about 23 years from now. This means that for mining rewards to remain at least at their current level, the product of Bitcoin's purchasing power and the current total transaction fees per block (Bitcoin purchasing power * Bitcoin total fees) would need to increase 100-fold over 23 years. Many people believe this scenario is unlikely, leading to numerous proposals for how to "solve" the problem. However, there's a problem with this approach. Protocol Security in Censorship-Resistant Blockchains is a Market Outcome, Not an Engineering Problem First, let me clarify that when I talk about censorship-resistant blockchains, I'm referring to pure Proof-of-Work blockchains. Proof-of-Stake blockchains are, by definition, not censorship-resistant, a topic we've explored in depth in previous articles. I've said before that Bitcoin's long-term security/settlement guarantees are based on an assumption, and that's exactly what I meant. It's impossible to prove it's "sufficient" in the long run. Either there's market demand for settlement guarantees through transaction fees, or there isn't. This is almost identical to whether there will be demand for Bitcoin in the future. If the answer to either of these questions is "no," Bitcoin will fail. I can't imagine a scenario where the answer is "yes" to one question and "no" to the other, so the conditions for failure are essentially the same. If people no longer need Bitcoin (the currency) or the Bitcoin protocol and network, it will fail. This argument is self-evident. This reality often leaves engineers (myself included) feeling unsatisfied. Consequently, numerous "solutions" have been proposed. These "solutions" can be broadly divided into two categories. They aim to either alter the supply or demand side of the fee market, or to establish tail issuance as a permanent reward for block generation. The problem is that neither approach has been proven effective. No matter how many adjustments are made to the supply or demand side of the fee market, there's no guarantee there will be any demand, let alone "sufficient" demand, whatever "sufficient" means in this context. This is obvious to most people. Despite this, simply because there's no "guarantee" or "proof," people still believe there are theoretically better designs than the current ones, which is why these proposals are proposed. This perspective is perfectly understandable, but I must emphasize that believing these proposals will work, just as believing the fee model will work, requires a great deal of faith. In reality, no one knows whether either of these proposals will work. The "security budget" of tail issuance can never be proven sufficient. Many people seem unclear that tail issuance, like solutions that incentivize perpetual settlement guarantees, suffers from the same unprovable problem. What level of tail issuance is considered "sufficient"? Setting a 1% tail issuance and targeting an arbitrary "security budget" can never guarantee settlement guarantees at any specific level—it's pure speculation. Because you can't predict the future purchasing power of the token, you always run the risk of issuing too little, forcing you to constantly adjust your monetary policy and even, in extreme cases, leading to hyperinflation. This further weakens the token's monetary properties and can potentially lead to a security death spiral, as plummeting token prices necessitate higher inflation rates to fund the "security budget." As mentioned above, my key point is that tail issuance does not guarantee the long-term security of a blockchain. Monero implemented a tail issuance mechanism in 2022, with the community expecting it to ensure the sustainability of block rewards. While this may be technically correct, as we've just seen, it provides no meaningful guarantee of settlement. While Monero miners can earn perpetual block rewards, Monero's monetary properties cannot compete with Bitcoin, so no one uses it as a store of value. The result is obvious: Monero's purchasing power has remained largely stagnant over the past decade. Compared to its strongest competitor, Bitcoin, the situation is even worse, with Monero's value plummeting over the years. In other words, while tail issuance sounds good, if your token has no value, no amount of tail issuance will be enough. This should serve as a warning to those who are blindly optimistic about blockchain inflation. At least within the Bitcoin community, it's widely believed that inflation is harmful to fiat currencies and society as a whole. Therefore, I'm surprised that some Bitcoin supporters believe that inflation is harmless to Bitcoin. The long-term value of any type of currency is primarily driven by low-frequency users seeking a long-term store of value. These users strongly prefer the currency unit they believe has the strongest monetary properties. If your blockchain doesn't provide these properties, they might use it for high-frequency trading, but not to store wealth during periods of economic inactivity. This is bad news for the value of your token. We must resist the temptation to engineer changes to Bitcoin's monetary properties. As I mentioned earlier, in order to maintain Bitcoin's current settlement guarantees over the next 25 years or so, it would need to increase the purchasing power of transaction fee rewards by approximately 100x. In fact, I think it's entirely possible.

Given that Bitcoin's price has increased over 100-fold over the past decade, while transaction fees have repeatedly and consistently exceeded 20 times the current BTC price. In other words, a 10-fold increase in price and a 10-fold increase in transaction fees over the next 25 years is not impossible in my opinion.

That is, as long as Bitcoin retains its exceptional monetary properties, I don't think this scenario is impossible. If we undermine these properties by changing the block size, introducing infinite inflation, or falling into the common mindset of Ethereum of constantly revising monetary policy, I think the risk is much greater than simply letting the market tell us whether there will be demand for Bitcoin in the long term.

In fact, the fundamental reason why the price of Bitcoin has not yet reached $10 million per coin is that we (as a society and a market at large) simply cannot be sure that the assumption that there will be sufficient future demand for Bitcoin is correct. Figuring out the answer to this question over time and accurately assessing its probability is precisely what markets are there for. Let the market play its part.

Joy

Joy